Aspiration Therapy—An Emerging Endoscopic Device for Treatment of Obesity

by Dilhana Badurdeen, MD; Margo Dunlap, RN; Michael Schweitzer, MD; and Vivek Kumbhari, MD

Drs. Badurdeen, Dunlap, and Kumbhari are with the Division of Gastroenterology and Dr. Schweitzer is with the Division of Surgery—all with Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions in Baltimore, Maryland.

Funding: No funding was provided.

Disclosures: Dr. Khumbari is a consultant for Medtronic (Minneapolis, Minnesota), ReShape Lifesciences (San Clemente, California), Boston Scientific (Marlborough, Massachusetts), and Apollo Endosurgery (Austin, Texas). He also receives research support from ERBE USA (Marietta, Georgia) and Apollo Endosurgery. All other authors have no disclosures.

Bariatric Times. 2019;16(2):8–10.

Abstract

Obesity and its comorbidities are a major health concern with significant costs associated with treating obesity-attributable medical problems. Aspiration therapy is an emerging endoscopic technique that could potentially provide patients with obesity with a safe, effective, minimally invasive alternative to other bariatric surgery procedures. Aspiration therapy, an endoscopically placed device that drains a portion of the stomach contents after every meal, removing up to 30 percent of calories consumed, has been shown to help patients, on average, lose 12 percent or more of their body weight. In this article, the authors provide an overview of this new therapy that may bridge the treatment gap between behavior modification and bariatric surgery among individuals with high body mass indices (BMIs) whom have not achieved sufficient results with behavior modifications alone.

Obesity, defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a body mass index (BMI) greater than 30kg/m2, could be considered a global health catastrophe. Detriments of obesity include economic burden, adverse effects on quality of life, reduced life expectancy, and serious medical comorbidities, such as cardiovascular disease, Type 2 diabetes, hypertension, cancer, and sleep apnea/sleep-disordered breathing.1

Bariatric surgery is the gold standard for weight loss, with significant and sustained weight loss outcomes.2–4 In the United States, 53.4 percent (116.1 million) of adults are eligible for a weight loss intervention, including pharmacologic and lifestyle modification.5 Unfortunately, only 14.7 percent (32.0 million) of American adults qualify for bariatric surgery, and fewer undergo the procedure due to the apprehension of “going under the knife” and fear of complications.2,3 In fact, in 2017, only 228,000 surgical procedures were performed for treatment of obesity, including intragastric balloons.6 It has thus become imperative to find additional options for weight loss, particularly among individuals with high BMIs in whom diet and lifestyle modifications typically do not achieve sufficient results. Aspiration therapy, an endoscopically placed device that drains a portion of the stomach contents after every meal, is an emerging endoscopic technique that could potentially provide patients with obesity with a safe and effective, minimally invasive alternative to other bariatric surgery procedures that is economically feasible and easily accessible.

Aspiration therapy has been shown to be an effective and safe treatment for obesity in adults aged 22 years or older with BMIs of 35.0 to 55.0 kg/m2 who have failed to achieve and/or maintain weight loss.7,8 Aspiration therapy should be used in conjunction with lifestyle modification that encourages healthy eating habits and reduction of calorie intake. Continuous medical monitoring of tube length is recommended for the duration of aspiration therapy as the patient’s abdominal girth decreases, so that the device disk remains flush against the skin. Placement of aspiration therapy costs 8,000 to 15,000 US dollars, based on region (i.e., rural versus metro markets, respectively). On average, the annual cost is 500 to 1,000 US dollars per patient for replacement supplies.9

The aspiration device has been shown to help patients, on average, lose 12 percent or more of their body weight.7,8 Statistically significant improvements in blood pressure, triglycerides, high-density lipoproteins (HDLs), and HbA1c have also been shown with aspiration therapy, though clinical significance has yet to be observed.8,10 Patients using aspiration therapy had a 55.3-percent estimated weight loss (EWL) at one year compared with 87.0-percent EWL at one year post-procedure for patients undergoing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB).10

Device History

The aspiration therapy device, AspireAssist® (Aspire Bariatrics, King of Prussia, Pennsylvania) received United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in June 2016 as a treatment device for obesity following the results of a randomized, controlled, 52-week study by Thompson et al.8 In this multicenter, United States pivotal trial, patients were randomized to receive either the aspiration therapy device and dietary counselling or lifestyle counselling alone. The mean percent EWL in the aspiration therapy group was 37.2±27.5 percent, compared with 13.0±17.6 percent in the lifestyle-only group.8 These results were inferior to data from previous studies in Swedish and United States cohorts.11–13 Though 21 percent of the study subjects dropped out of the aspiration therapy arm, the results exceeded the American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE)-recommended thresholds for efficacy and safety of endoscopic primary obesity therapies,14 and the device subsequently received FDA approval as an endoscopic bariatric therapy.

Mechanism for Weight Loss

Aspiration therapy involves endoscopic placement of a customized gastrostomy tube. Approximately 20 minutes after meal consumption, the patient is instructed to aspirate gastric contents into the toilet. The basis of weight loss comes from forceful and effective control of calorie absorption, which is a key principle of weight management therapy. Sullivan et al7 demonstrated that only 50 to 80 percent of the observed weight loss among patients undergoing aspiration therapy could be attributed to the device, thus implying the existence of additional mechanisms of action. The authors hypothesized that the dietary changes needed for effective aspiration therapy, such as chewing food well, avoiding snacking, and developing a plan to accommodate aspiration inside and outside the home, reinforces some of the behavioral principles of weight management.7 Additionally, the authors suggested that the fistula between the stomach and abdominal wall might affect gastric distension, resulting in earlier satiation.7 The authors postulated that aspiration therapy might encourage greater awareness of food choices, and that slower eating promotes recognition of satiety by the brain at an earlier point in time.7

Unlike other endoscopic bariatric therapies, aspiration therapy requires significant patient engagement in the way of motivation and lifestyle modifications; however, a distinguishing factor of the aspiration device is that it does not operate automatically—the patient is responsible for manually operating the device—which requires an additional level of commitment from the patient not required by other bariatric endoscopic and surgical procedures. The challenge is not just educating patients on how to use the device, but also helping them stay motivated to make the lifestyle changes needed to achieve significant and clinically meaningful weight loss. Once patients gain momentum with their weight loss, they might feel more empowered and in control of their food choices.7

There was initial concern with aspiration therapy over the potential for patients to overeat or develop eating disorders, such as binge eating syndrome or bulimia.7,8 However, new symptoms of disordered eating or evidence of increasing food intake during or between meals, whether to make up for the reduced energy intake or because subjects felt the procedure gave them a license to overeat, have not been observed.8,14 Rather, patients using aspiration therapy reported feeling more in control of their eating and feeling less hungry.7

Device Components

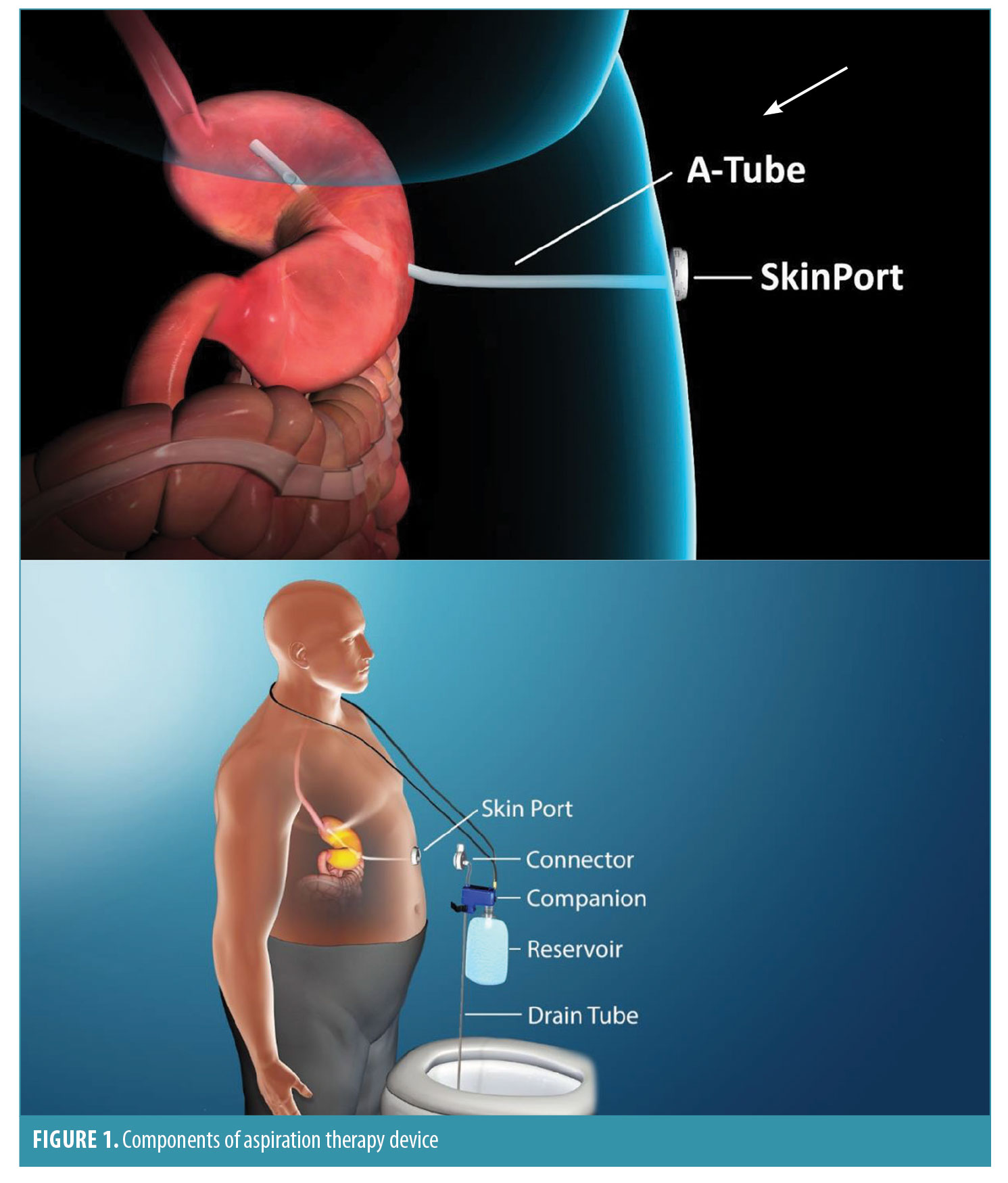

The aspiration therapy device consists of an A tube, skin port, connector, companion, and reservoir (Figure 1). The A tube is similar to a gastrostomy tube, except it possesses holes in the intragastric portion to allow aspiration of gastric contents. The skin port consists of a one-inch diameter, low-profile valve that connects to the external end of the A tube. To prevent leakage of gastric contents, the valve remains closed except when engaged by the connector. The connector is a detachable external device that unites with the skin port and opens the skin port valve, which allows aspiration of a portion of the meal that was consumed. Incorporated into the connector is a counter that tracks the number of times the connector is attached to the skin port. When 115 aspiration cycles have been completed (approximately 5–6 weeks of therapy), the connector locks and the skin port can no longer be accessed for aspiration. This provides an additional layer of safety against long-term, unsupervised use of aspiration therapy. Patients must then return to the clinic to obtain a new connector to resume aspiration therapy. The companion is a siphon that allows a two-way flow of fluids, through which patients can flush the stomach with water from a 600mL soft water bottle to facilitate aspiration. The drain tube allows drainage of aspirated gastric contents into the toilet.

Tube Placement

The A tube is analogous to a a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube and is placed in a similar fashion. Patients undergo an outpatient endoscopic procedure that takes approximately 20 minutes and is performed under conscious sedation. A large abdominal girth does not hinder safe A tube placement, and the procedure is aborted in less than one percent of patients due to inability to transilluminate.8 At roughly Day 10 postgastrostomy tube placement, the A tube is cut to within 1cm of the abdominal skin and attached to the skin port.

Principles of Aspiration

Aspiration therapy requires a high degree of patient engagement; thus, patients undergoing aspiration therapy must be trained on how to use the device. Patients are instructed to chew food thoroughly to avoid A tube blockage during aspiration. The internal diameter of the A tube is 6.0mm, so large food particles will block the lumen and aspiration holes. The blockage can be cleared by squeezing the reservoir and forcing water into the A tube and stomach; however, it will likely get blocked again fairly quickly, preventing drainage, if the food particles are larger than 6mm, thus preventing optimal drainage of calories. The ideal time to aspirate is roughly 20 to 30 minutes after each of the three main meals. Once the connector is attached to the skin port, it takes approximately 5 to 10 minutes to drain food matter through the tube into the toilet.

Aspiration of all consumed calories, particularly rapidly absorbed liquid calories, does not occur using the aspiration device; thus, dietary discretion is a critical component of aspiration therapy. A maximum of 30 percent of caloric content per meal can be aspirated using the device.10 To maximize successful weight loss, patients must chew food thoroughly and drink a sufficient amount of water with meals. Importance of regular and complete aspiration after each meal and the negative consequence of snacking between meals must be emphasized and reinforced to the patient. Adherence to the device has been shown to be approximately 80 percent at one year and 60 percent at two years.11 The device can remain in place indefinitely.

Side Effects and Complications

Complications of aspiration therapy are similar to those of standard PEG tube placement. Perioperative complications include nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, peristomal inflammation, and peristomal bacterial infections. Severe adverse events are rare and include peritonitis requiring intravenous (IV) antibiotics and severe abdominal pain.8

The most common adverse events associated with aspiration therapy are abdominal pain, dyspepsia, peristomal irritation, gastrostomy site skin infections, peristomal granulation tissue, buried bumper syndrome, prepyloric ulcer formation, and persistent gastro cutaneous (GC) fistula on tube removal.8,12 Peristomal granulation tissue can occur about 1 to 2 months after A tube placement and can be particularly bothersome, often necessitating the use of silver nitrate.8 Persistent GC fistulas appear to be related to the dwell time of the A tube and are more prevalent if the tube is left in for more than a year.

Side effects of aspiration therapy include occasional indigestion, nausea, vomiting, constipation, and diarrhea. Electrolyte imbalance and hypokalemia have not been reported (though theoretically they are possible due to chronic loss of hydrogen and chloride ions from aspiration, with resultant renal secretion of potassium ions11; thus, potassium supplementation is not considered necessary unless the patient is taking concomitant potassium-lowering medications, such as diuretics.

Less than five percent of patients on aspiration therapy are hospitalized due to periprocedural complications, and less than five percent per year require an endoscopy to remove or replace the A tube.11 Serious adverse events are seen in approximately 3.6 percent of patients, with no reported major debility or death.8

Contraindications

Aspiration therapy should not be used in patients with eating disorders, such as binge eating disorder, bulimia nervosa, or night eating syndrome, or in patients with moderate overweight for short durations. Device placement should be deferred in patients with a history of gastrointestinal disease, previous abdominal surgery including abdominal mesh placement, or bariatric surgery that would increase the risk of adverse events associated with endoscopic A tube placement. Other contraindications include patients with serious cardiopulmonary disease, uncontrolled hypertension, chronic abdominal pain, history of severe psychiatric disorder(s) (e.g., major depressive disorder), inflammatory bowel disease, anemia, pregnancy or lactation, coagulation disorders, esophageal strictures, severe gastroparesis, or gastric outlet obstruction.8

Limitations

The aspiration therapy device was introduced to the market amid controversy and criticism as “FDA-assisted bulimia” and a “stomach sucker,” and has since had limited acceptance and low use.15,16 Significant patient commitment, motivation, and adherence are required for successful and sustained weight loss using this device. In addition to adherence to properly operating the device, chewing food thoroughly is a notable critical factor in achieving successful weight loss using this device; thus, patients who fail to adhere to thoroughly chewing their food likely will not achieve optimal results. It takes approximately one month for the conscious effort of chewing thoroughly to become an ingrained habit.7 Even though patients have demonstrated statistically significant weight loss using aspiration therapy, there is insufficient evidence supporting significant improvements in obesity-related comorbidities.17,18

Advantages

Aspiration therapy is a reversible procedure that has been shown to produce approximately 12-percent mean percent body weight loss at 52 weeks.8 These results exceed those typically achieved with intensive lifestyle therapy alone.8,12 Aspiration therapy is minimally invasive, which might make it more appealing to some patients; less costly (e.g., no hospital stay required); and less risk of complications, such as bleeding, leaks, strictures, and malabsorption, when compared with other bariatric surgical procedures. Additionally, the anatomy of the gastrointestinal tract is not altered when placing the aspiration device, which suggests the procedure is easily reversible and likely will not hinder subsequent bariatric surgery, should the patient fail to achieve adequate weight loss and require a more stringent approach. Aspiration therapy is also a suitable weight-loss option for patients who do not qualify for an intragastric balloon due to a BMI above 40kg/m2, severe reflux, or a large hiatal hernia.17

In addition to weight loss, statistically significant improvement in plasma C-reactive protein (CRP), plasma alanine transaminase (ALT), fasting blood glucose concentration, and HbA1c have been observed with the use of aspiration therapy.12 Notably, there is also enhanced quality of life (as measured with EQ-5D, improved from 0.73 (0.27) to 0.88 (0.13), p<0.01) despite the presence of a gastrostomy tube and the onus of aspirating three times a day.11 Unlike the intragastric balloon, where recidivism is common, patients who continued using aspiration therapy for 2 to 4 years reportedly were able to maintain their weight or continue to lose weight, as long as they continued to adhere to the aspiration regimen.13,19

Conclusion

Despite the poor acceptance of this procedure, aspiration therapy has been shown to be a safe, effective method of weight loss in certain individuals who are highly motivated and adherent.8 Patients who lost five percent or more of their body weight by Week 14 of aspiration therapy were defined as early responders, and this predicted successful weight loss at Week 52.8 Further studies are needed to better determine the type of patient who will benefit the most from this procedure.

The AspireAssist® is a cost-effective, technically simple endoscopic bariatric therapy with minimal side effects; however, it is not a quick fix for Class 2 and 3 obesity. It is, however, a reasonable alternative for select patients with a BMI more than 35kg/m2 who seek a less invasive endoscopic weight loss option and are highly motivated.

References

- Poirier P, Giles TD, Bray GA, et al. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: pathophysiology, evaluation, and effect of weight loss: An update of the 1997 American Heart Association Scientific Statement on Obesity and Heart Disease from the Obesity Committee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism. Circulation. 2006;113(6):898–918.

- Ju T, Rivas L, Arnott S, et al. Barriers to bariatric surgery: Factors influencing progression to bariatric surgery in a U.S. metropolitan area. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018 Dec 6.

- Nguyen NT, Masoomi H, Magno CP, et al. Trends in use of bariatric surgery, 2003-2008. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;213(2):261–266.

- le Roux CW, Heneghan HM. Bariatric surgery for obesity. Med Clin North Am. 2018;102(1):165–182.

- Stevens J, Oakkar EE, Cui Z, et al. US adults recommended for weight reduction by 1998 and 2013 obesity guidelines, NHANES 2007-2012. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2015;23(3):527–531.

- ASMBS. Estimate of bariatric surgery numbers, 2011-2017. https://asmbs.org/resources/estimate-of-bariatric-surgery-numbers. Accessed February 1, 2019.

- Sullivan S, Stein R, Jonnalagadda S, Mullady D, Edmundowicz S. Aspiration therapy leads to weight loss in obese subjects: a pilot study. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(6):1245–1252.e1-5.

- Thompson CC, Abu Dayyeh BK, Kushner R, et al. Percutaneous gastrostomy device for the treatment of Class II and Class III obesity: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017 Mar;112(3):447–57.

- Frey M. AspireAssist stomach pump for weight loss. September 10, 2018. https://www.verywellfit.com/aspireassist-the-stomach-pump-for-weight-loss-4122351. Accessed February 1, 2019.

- Wilson E, Norén E, Axelsson L, et al. A comparative 100-participant 5-year study of aspiration therapy versus Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: First year results. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13(10 Suppl):S25–S26.

- Norén E, Forssell H. Aspiration therapy for obesity; a safe and effective treatment. BMC Obes. 2016;3:56.

- Forssell H, Norén E. A novel endoscopic weight loss therapy using gastric aspiration: results after 6 months. Endoscopy. 2015;47(1):68–71.

- Gaur S, Levy S, Mathus-Vliegen L, Chuttani R. Balancing risk and reward: A critical review of the intragastric balloon for weight loss. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81(6):1330–1336.

- ASGE/ASMBS Task Force on Endoscopic Bariatric Therapy, Ginsberg GG, Chand B, et al. A pathway to endoscopic bariatric therapies. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74(5):943–953.

- Miller SG. Stomach sucker: How does new weight-loss device work? June 22, 2016. https://www.livescience.com/55161-weight-loss-device-aspire-assist.html. Accessed February 1, 2019.

- Fox M. FDA approves weight loss stomach pump AspireAssist to combat obesity. June 14, 2016. https://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-news/fda-approves-weight-loss-stomach-pump-aspireassist-combat-obesity-n592141. Accessed February 1, 2019.

- Kumbhari V, Okolo PI. Editorial: aspiration therapy for weight loss: is the squeeze worth the juice? Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(3):458–589.

- Hill C, Khashab MA, Kalloo AN, Kumbhari V. Endoluminal weight loss and metabolic therapies: current and future techniques. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2018;1411(1):36–52.

- Thompson CC, Abu Dayyeh BK, Kushnir V, et al. Aspiration therapy for the treatment of obesity: 2-4 year results of the PATHWAY multicenter randomized controlled trial. Presentated at Obesity Week 2018; 2018 Nov 15; Nashville.

Category: Emerging Technologies, Past Articles