Mesenteric Venous Thrombosis following Bariatric Surgery

This activity has expired.

This activity has expired.

Course Overview

Bariatric surgery has become the mainstay treatment for obesity with many thousands procedures performed annually. This article highlights the physiopathology, risks factors, clinical presentation, and treatment of mesenteric vein thrombosis, an uncommon but life-threatening complication that can occur after bariatric surgery.

Course Description

This continuing education course is designed to educate, through independent study, integrated healthcare clinicians who care for patients with overweight or obesity, including the metabolic and bariatric surgical patient population.

Course Objectives

- Upon completion of this program, the participant should be able to:

- Explain the physiopathology of mesenteric venous thrombosis.

- Recognize presentation of mesenteric venous thrombosis in the clinical setting.

- Identify diagnostic study of choice for mesenteric venous thrombosis.

- List the different therapeutic options available for the management and treatment of mesenteric venous thrombosis.

Target Audience

This accredited program is intended for nurses who treat bariatric and metabolic surgery patients.

Completion Time

This educational activity is accredited for a total of 1.0 contact hour (Nursing).

Accreditation Summary

This educational program is provided by Matrix Medical Communications. Provider approved by the California Board of Registered Nursing, Provider Number 14887. Activity approved for 1.0 contact hour.

Provider Contact Information

Emily A. Scullin Matrix Medical Communications, 1595 Paoli Pike, Suite 201, West Chester, PA 19380; Email: [email protected]

Sponsorship and Support

This continuing education activity is financially supported by Medtronic (Minneapolis, Minnesota).

Tracy Martinez, RN, BSN, CBN

Ms. Martinez is Department Editor of Integrated Health Continuing Education for Bariatric Times; and Program Director of Wittgrove Bariatric Center in Del Mar, California.

A Message from the Department Editor

Dear Colleagues:

As practitioners, we follow detailed policies and procedures to safely prepare our patients for bariatric and metabolic surgery. Thankfully, the perioperative management is usually safe and efficient. However, recognition of and preparation for the unexpected is equally important. Dr. Brodsky provides us with a comprehensive clinical picture of the pathophysiology, assessment, recognition, treatment, and prevention of a potentially fatal surgical complication—rhabdomyolysis. Rhabdomyolysis is a serious syndrome caused by direct or indirect muscle injury. Individuals with severe obesity are at greater risk than the general population for developing rhabdomyolysis, and patients undergoing bariatric surgery are at an even higher risk for developing this dangerous complication. Its incidence might be higher than originally thought. We hope you enjoy this article and find the knowledge gained from participating in this educational activity to be useful when developing your own treatment protocols for rhabdomyolysis, with optimal patient outcomes. I want to thank Dr. Brodsky for sharing his expertise with us on this important topic.

My best to you,

Tracy Martinez, RN, BSN, CBN

by Samuel Szomstein, MD FACS, FASMBS, and Abraham Betancourt, MD

Dr. Szomstein is the Director of the Fellowship Program in Advanced Minimally Invasive Surgery and Bariatrics and the Associate Chairman of the Bariatric and Metabolic Institute and Section of Minimally Invasive Surgery in the Department of General and Vascular Surgery at Cleveland Clinic Florida in Weston, Florida. Dr. Betancourt is an Advanced Gastrointestinal/Minimally Surgery Fellow at Cleveland Clinic Florida in Weston, Florida.

Funding: This article is part of a continuing education activity financially supported by Medtronic (Minneapolis, Minnesota)

Disclosures: Drs. Szomstein and Betancourt report no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Abstract: Superior mesenteric vein thrombosis is a rare complication following laparoscopic bariatric surgery. In addition to accepted risk factors of hypercoagulability and local-abdominal processes, increased intra-abdominal pressure, intraoperative manipulation, or extrinsic anatomical compression might also contribute to venous compromise. Early identification and treatment can result in successful outcomes and decreased morbidity in this patient population. All clinicians working with bariatric surgery should be aware of the potential for superior mesenteric vein thrombosis after bariatric surgery, especially when a patient presents with postoperative abdominal pain. In this article, the authors review the pathophysiology and clinical signs of mesenteric vein thrombosis and discuss diagnosis and treatment.

Keywords: Abdominal pain, bariatric surgery complications, laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, mesenteric vein thrombosis, bariatric complications, postoperative complications, portal thrombosis

Bariatric Times. 2019;16(5):8–11.

Introduction

Mesenteric venous thrombosis (MVT) is a clot that blocks blood flow in one or more of the mesenteric veins, major veins that drain blood from the intestine. The superior mesenteric vein is most commonly involved.

MVT, first described as a distinct cause of mesenteric ischemia by Warren and Eberhard in 1935,1 now accounts for 5 to 15 percent of all cases of mesenteric ischemia.1,2 Thrombosis of the superior mesenteric vein is exceptional and potentially severe.3 This type of ischemia has been described after bariatric surgery; laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG), Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), and duodenal switch (DS).4,5 Of 5,706 patients analyzed after laparoscopic bariatric surgery, 17 (0.3%) had portomesenteric vein thrombosis and appear to be more common after LSG.6

Pathophysiology

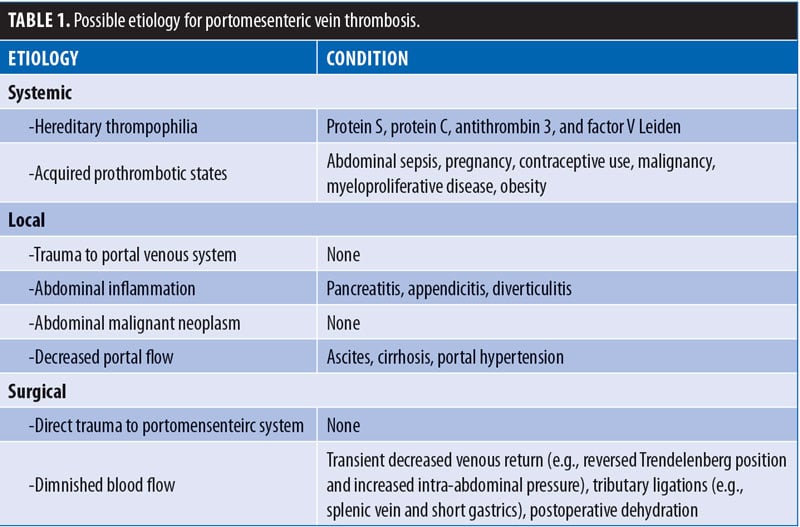

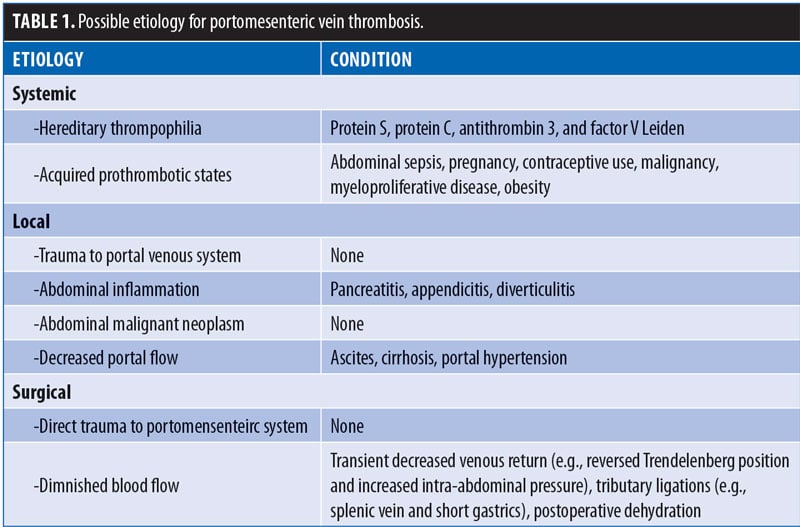

Possible etiologies may be systemic (e.g., inherited hypercoagulable or acquired prothrombotic states) or local (e.g., intra-abdominal inflammatory or neoplastic disease, diminished flow in cirrhosis, or portal hypertension) [Table 1]).

The pathophysiology of thrombosis of the superior mesenteric vein is multifactorial. The laparoscopic abdominal pressure (>14mm Hg) associated with a marked position in bariatric surgery reduces the venous flow by 50 percent, which may increase the risk of thrombosis. Hypercapnia induced by CO6 insufflation causes sympathetic vasoconstriction, which increases peripheral resistance, average arterial pressure, pulmonary arterial pressure, and pulmonary capillary wedge pressure.7 In addition, soft tissue trauma during bariatric surgery (i.e., manipulation of the small intestine during short gastric bypass or duodenal switch) releases tissue factors that could cause a mesenteric venous thrombosis in patients with a previously undiagnosed hypercoagulable state.5

In addition to the rare, sporadic cases encountered in general laparoscopic surgery, the following are three possible mechanisms by which laparoscopic bariatric surgery might instigate MVT:

The change in blood flow (namely, venous return from the stomach) occurs after LSG because of the division of the short gastric vessels. The altered flow may be a factor in MVT promotion, similar to the state after fundoplication, which has been implicated before in this regard.8–10

In LSG or RYGB, direct physical contact with the splenic vein is possible while the surgeon is working in the lesser omental bursa. Intimal damage may inadvertently occur and cause later thrombosis.

After bariatric surgery, patients are usually discharged from the hospital soon after the procedure. Some patients encounter difficulty in reaching the suggested 2L per day fluid intake and experience various degrees of dehydration. This may put them at a higher risk for thrombotic complications, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and MVT.11,12

Risk factors for MVT

Significant relationships exist between history of cancer, diabetes status, and MVT. Other factors such as smoking status and levothyroxine use also have described.13 The incidence of thrombosis in cancer patients can be as high as 15 percent. Hyperthyroidism is associated with a hypercoagulable state,14 as it seems to be associated with increased levels of fibrinogen, factor VIII, factor X, and Von Willebrand factor antigen.15 Type 2 diabetes is known to be associated with increased risk of thrombosis and cardiovascular disease. Due to abnormal modulation of plasma proteins related to coagulation, diabetes patients are also prone to hypercoagulable state.16

Obesity is considered a hypercoagulable state with a higher-than-average risk for thromboembolic events. This is attributed to several factors, including the chronic inflammatory state associated with obesity, increased abdominal pressure, lower-extremity venous stasis, and a sedentary lifestyle.16

Goitein et al,6 conducted a retrospective, multicenter study of 5,706 patients with morbid obesity diagnosed with portomesenteric vein thrombosis (PMVT) following laparoscopic bariatric surgery. Among 17 patients who developed PMVT following surgery, nearly one-third had a history of VTEs. These results were statistically significant when compared with the patients who did not develop PMVT (P<0.001; relative risk[RR]: 9.8), making a history of VTEs an important risk factor for MVT formation.6

Clinical Presentation

MVT usually manifests as nonspecific abdominal pain, however, the clinical presentation varies widely and the diagnosis can potentially be delayed. Patients may experience nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, or gastrointestinal tract bleeding. Most patients have had symptoms for more than two days before seeking medical care. Physical findings vary and range from no physical findings to low-grade fever, mild abdominal tenderness, peritoneal signs, or frank shock due to bowel ischemia.6

Diagnosis and Treatment

Computed tomography (CT) scanning has become the diagnostic modality of choice and can be relied on to provide a correct diagnosis in 90 percent of the cases.17,18 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), duplex ultrasonography, and arteriography are other modalities that can be used; however, these might be either less sensitive or difficult to use in urgent situations.17

The CT findings of MVT include mesenteric venous central lucency, mesenteric fat stranding, and edematous or dilated small bowel.17 CT is also useful for its ability to diagnose other pathologic features that could also present with vague abdominal symptoms after bariatric surgery.18

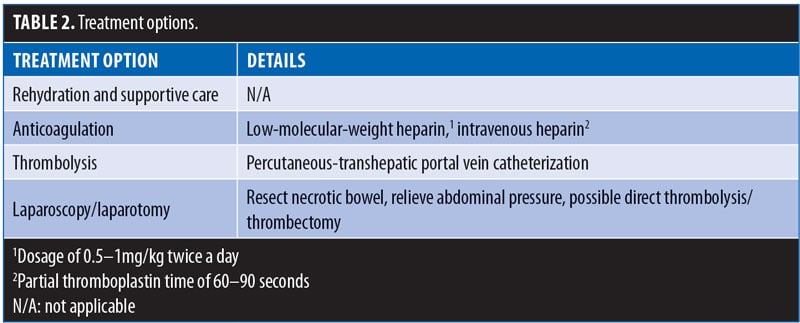

Treatment options vary according to the severity of the disease and its sequelae (Table 2). Initial supportive measures include rehydration and bowel rest. Full anticoagulation with either subcutaneous low-molecular-weight (LMW) heparin (1.5–2mg/kg, divided into 2 daily administrations) or intravenous (IV) unfractionated heparin (titrated to a partial thromboplastin time of 60–90 seconds) is given to patients who do not develop bowel ischemia or necrosis. This treatment is continued and changed to oral anticoagulants (target international normalized ratio: 2.5-3) that should be continued for several months (the length of which will depend on coagulation profiles and a formal hematologic consultation).19–20 For patients with a more severe presentation and with symptoms and/or imaging findings compatible with an ischemic bowel, percutaneous, transhepatic thrombolytic therapy may be attempted, however, this treatment requires the proper technical setup and expertise, both of which might not be available in all institutions.

Patients with peritonitis, sepsis, or perforation require an immediate exploration and resection of the necrotic bowel, if identified. A direct portomesenteric thrombectomy or thrombolysis is also possible in select cases.21,22

Conclusion

MVT is an infrequent complication of bariatric surgery. Its true incidence is not known and is probably underestimated. A previous history of VTEs is an important risk factor for MVT formation, and its presence should prompt clinicians to consider an uncompromising prophylactic regimen for the patient. Familiarity with this entity, and a high index of suspicion, will allow for a prompt diagnosis and treatment, leading to a swift and favorable resolution.

References

- Warren S, Eberhard TP. Mesenteric venous thrombosis. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1935;61:102–121.

- Ottinger LW, Austen WG. A study of 136 patients with mesenteric infarction. Surg Gyencol Obstet. 1967;124:251–261.

- Swartz DE, Felix EL. Acute mesenteric venous thrombosis following laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. JSLS. 2004;8(2):165–169.

- Gandhi K, Singh P, Sharma M, Desai H, Nelson J, Kaul A. Mesenteric vein thrombosis after laproscopic gastric sleeve procedure. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2010;30(2):179–183.

- Johnson CM, de la Torre RA, Scott JS, Johansen T. Mesenteric venous thrombosis after laparoscopic Roux-enY gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2005;1(6):580–582; discussion 582–583. Epub 2005 Oct 3.

- Goitein D, Matter I, Raziel A, et al. Portomesenteric thrombosis following laparoscopic bariatric surgery: incidence, patterns of clinical presentation, and etiology in a bariatric patient population. JAMA Surg. 2013;148(4):340–346.

- Haglund U, Norlen K, Rasmussen I, et al. Complications related to pneumoperitoneum. In: Bailey RW, Flowers JL, eds. Complications of Laparoscopic Surgery. St. Louis: Quality Medical Publishing Inc.; 1995: 45–48.

- James AW, Rabl C, Westphalen AC, Fogarty PF, Posselt AM, Campos GM. Portomesenteric venous thrombosis after laparoscopic surgery: a systematic literature review. Arch Surg. 2009;144(6):520–526

- García Díaz RA1, Rodríguez-Sanjuán JC, Domínguez Díez RA, et al. Fatal portal thrombosis after laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2005;97(9):666–669.

- Kemppainen E, Kokkola A, Sirén J, Kiviluoto T. Superior mesenteric and portal vein thrombosis following laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. Dig Surg. 2000;17(3):279–281.

- Barba CA, Harrington C, Loewen M. Status of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis among bariatric surgeons: have we changed our practice during the past decade? Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2009;5(3):352–356. Epub 2008 Nov 24.

- Becattini C, Agnelli G, Manina G, Noya G, Rondelli F. Venous thromboembolism after laparoscopic bariatric surgery for morbid obesity: clinical burden and prevention. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2012;8(1):108–115.

- Moon RC, Ghanem M, Teixeira AF, et al. Assessing risk factors, presentation, and management of portomesenteric vein thrombosis after sleeve gastrectomy: a multicenter case-control study. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018;14(4):478–483. Epub 2017 Oct 26.

- Squizzato A, Romualdi E, Büller HR, Gerdes VE. Clinical review: thyroid dysfunction and effects on coagulation and fibrinolysis: a systematic review. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(7):2415–2420.

- Hooper JM, Stuijver DJ, Orme SM, et al. Thyroid dysfunction and fibrin network structure: a mechanism for increased thrombotic risk in hyperthyroid individuals. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(5):1463–1473.

- Uchimura I, Kaibara M, Nagasawa M, Hayashi Y. Effect of circulating tissue factor on hypercoagulability in type 2 diabetes mellitus studied by rheometry and dielectric blood coagulometry. Biorheology. 2016;53(5-6):209–219.

- Morasch MD, Ebaugh JL, Chiou AC, et al. Mesenteric venous thrombosis: a changing clinical entity. J Vasc Surg. 2001;34:680–684.

- Kumar S, Sarr MG, Kamath PS. Mesenteric venous thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1683–1688.

- Condat B, Pessione F, Helene Denninger M, Hillaire S, Valla D. Recent portal or mesenteric venous thrombosis: increased recognition and frequent recanalization on anticoagulant therapy. Hepatology. 2000;32(3):466–470.

- Condat B, Pessione F, Hillaire S, et al. Current outcome of portal vein thrombosis in adults: risk and benefit of anticoagulant therapy. Gastroenterology. 2001;120(2):490–497.

- Kercher KW, Sing RF, Watson KW, et al. Transhepatic thrombolysis in acute portal vein thrombosis after laparoscopic splenectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2002;12(2):131–136.

- Ozkan U, Oğuzkurt L, Tercan F, Tokmak N. Percutaneous transhepatic thrombolysis in the treatment of acute portal venous thrombosis. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2006;12(2):105–107.

Category: Past Articles, Review