The Role of Psychological Testing for Bariatric/Metabolic Surgery Candidates

by Leslie J. Heinberg, PhD

Dr. Heinberg is Professor of Medicine, Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine of Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio.

FUNDING: No funding was provided.

DISCLOSURES: Dr. Heinberg reports no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

ABSTRACT

Mental health professionals are considered to be a vital part of multidisciplinary assessment and treatment of bariatric surgery patients. The vast majority of bariatric programs include psychological evaluation prior to surgery and most of these providers augment their clinical interview with psychometric testing. Bariatric surgery candidates are a psychiatrically vulnerable population and a number of psychosocial and behavioral indicators may impact post-surgical adherence and weight loss outcomes. However, there is little consensus on what constitutes an appropriate evaluation and testing battery.

The following review will explore advantages for psychological testing and the potential value it may add to the assessment and pre-treatment recommendations of weight loss surgery patients. The use of both routine and selective psychological testing will be reviewed as well as guidelines for appropriate test selection. Finally, commonly utilized measures of personality, psychopathology, eating behavior, quality of life, alcohol use, and cognitive functioning will be reviewed with a focus on those that have published bariatric norms.

Introduction

Psychological assessment is a widely utilized and accepted part of a multidisciplinary assessment for weight loss surgery candidates.[1] When bariatric programs have been surveyed, 98.5 percent endorse utilizing clinical interviews, with 48 to 85 percent including psychological testing measures.[2–4] Despite this almost universal adoption of psychological evaluation, the field of bariatrics, and more specifically bariatric psychology, has not reached a consensus on the most appropriate type of evaluation. Furthermore, consensus on whether testing should be routine or more selective has not been affirmed.

The following review will explore why psychological testing has been so frequently adopted and the potential value it may add to the assessment and pre-treatment process of weight loss surgery patients. Although these instruments are also of significant value after surgery in assessing outcomes, the majority of research has focused on the preoperative evaluation. Thus, this review will heavily focus on psychological testing in the preoperative patient. Next, a discussion of both routine and selective psychological testing will be reviewed. This will be followed by a discussion of issues in appropriate test selection. Finally, commonly utilized measures of personality, psychopathology, depression, eating behavior, and quality of life will be explored.

Outside of this review a number of excellent resources are also available to providers wishing to learn more about psychological testing.

The Allied Health Sciences Behavioral Health Committee of the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) published Suggestions for the Pre-Surgical Psychological Assessment of Bariatric Surgery Candidates in 2004.5 These suggestions also include important domains for clinical psychiatric interviews. The suggestions are currently under revision and an update should be available in the next year. The current version can be found on the ASMBS website http://asmbs.org/2012/06/pre-surgical-psychological-assessment/.[5] Additionally, an updated chapter on assessment of bariatric surgery candidates was written by Peterson et al in 2012 and can be found in Psychosocial Assessment and Treatment of Bariatric Surgery Patients.[6] Both of these resources provide a more comprehensive review of the measures utilized by mental health professionals.

Importance of Routine Psychological Testing

Bariatric surgery is the most effective treatment for severe obesity (BMI≥40kg/m²),[7,8] which makes it an increasingly common surgical procedure.[9] Some individuals fail to lose the expected amount of weight, whereas others regain considerable weight within the first few years following surgery.[7,8] Although many biological and physiological mechanisms have been posited, many of the putative factors relate to behavior, adherence, and psychiatric comorbidity.[10–12] Beyond the adherence demands of surgery, extreme obesity is associated with significant psychosocial comorbidity, and patients who present for bariatric surgery are considered to be a psychiatrically vulnerable population.[1,13,14] A number of studies have demonstrated that patients burdened by depression and other psychiatric difficulties may have greater difficulty with weight loss after surgery.[10,12,15] As a consequence, psychological evaluation of bariatric surgery candidates has become the norm within the majority of programs. Furthermore, the majority of insurance companies require an assessment by a mental health professional prior to approving weight loss surgery.[2]

Given the time required by the clinician and the patient—as well as the expense—it is helpful to outline why some degree of routine testing is beneficial. Although a clinical interview conducted by an experienced provider may be highly informative, testing may provide information that cannot be adequately covered or accessible within the time limits of the interview. This may be especially true for lower-base rate disorders or behaviors. For example, the clinical interview may focus on common comorbid psychiatric diagnoses, such as depression and binge eating disorder. However, psychological testing may point to less common difficulties, such as thought dysfunction, that are not readily apparent.

Testing can also be useful in uncovering information about the candidate that may not be disclosed during the interview. Patients are frequently very concerned about the requirement for a psychological evaluation. Patients may believe that if the professional uncovers something negative, it will adversely affect their ability to undergo surgery. Thus, the evaluation is seen as an obstacle between them and a very strongly desired outcome. As such, many patients undergoing these evaluations are motivated to present themselves in an overly positive manner. One study found that approximately two-thirds of bariatric surgery candidates score at least a standard deviation above the mean on an instrument assessing social desirability and that these elevations were associated with underreporting of clinical symptoms.[16] Conversely, others may incorrectly attempt to magnify their psychological distress believing that doing so will strengthen their candidacy for surgery. Many of the measures described in this article have indicators of “faking good,” “faking bad,” or “attempts to portray oneself in an overly favorable light.” Although this can impact the validity of a test, there is evidence that 94 percent of patients can produce a valid profile on a second testing attempt if given instructions to repeat the tests with “a mindset of rigorous openness and honesty.”[17] Patients may also feel more comfortable endorsing problematic behaviors on a measure rather than endorsing it out loud or with a new provider. Individuals may be more forthcoming when completing a questionnaire on a computer than in a paper-and-pencil format.[18] Finally, patients may unwittingly omit important information during the clinical interview because they forget, do not think it is important, or run out of time. Psychological testing allows for a much larger breadth of assessment than what can usually be uncovered in a 60- to 90-minute evaluation.

Psychological testing can also build rapport with the patient.[19] Reviewing the findings of the test battery, especially with a focus on strengths and weaknesses, demonstrates that the provider has insight into the patient’s psychological functioning, expertise in the field, and empathy toward the patient’s experience. Furthermore, it can help drive more individualized recommendations and treatment planning. These individualized recommendations may lead to greater engagement in the surgical process, which, in turn, may enhance longer-term outcomes.[6] This kind of collaborative treatment planning is beneficial for the patient as well as the multidisciplinary team.[6]

Measures with bariatric norms can also be very useful to clinicians. Although clinical experience is invaluable, specific objective data can help better compare an individual to the population. For example, knowing that a patient’s depression is more than a standard deviation greater than other bariatric patients can put the need for treatment into clearer context. The use of common measures can also help improve communications between providers, settings, and surgical centers as well as give opportunities for sharing outcome data across multiple sites.

Finally, it has been noted that objective testing can have an advantage for the provider in reducing risk and professional liability.[5] Data from well-established instruments may prove to be helpful in supporting one’s clinical decision making and recommendations, whereas clinical impressions alone may be more difficult to defend.

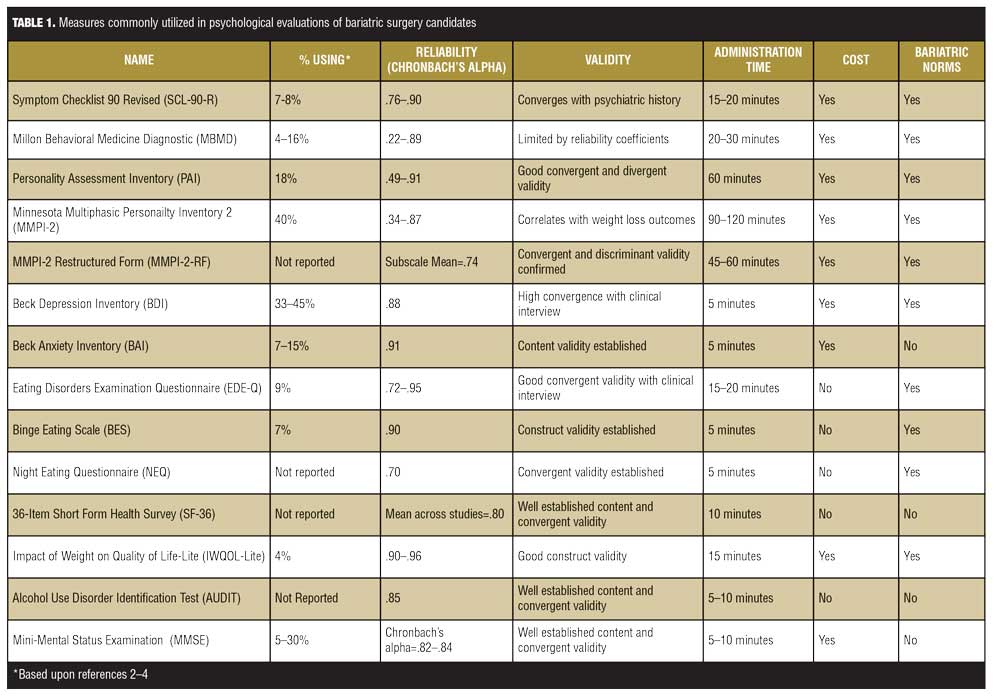

Limitations. Although the preceding discussion outlines benefits of psychological testing, there are a number of limitations. Beyond the significant time investment by both patients and clinicians, many tests have specific costs required by the publisher (see Table 1 for additional information). Additionally, interpretation time must be billed. Some insurers do not reimburse for psychological testing, require pre-authorization for such services, or reimburse at a very minimal level. Psychological testing is also limited for those with reading difficulties, vision problems, or for patients who are non-native English speakers. It is also important to note that bariatric behavioral health is a nascent field. The majority of measures are not thoroughly described in this population and have only limited data on the predictive utility of psychological testing. It is vital that researchers examine the association between psychological testing and post-surgical outcome measures.

Importance of Selective Psychological Testing

Psychological testing should always be in addition to a structured or semi-structured interview conducted by a mental health professional with bariatric experience. Although advantages of more routine testing were described previously, the use of selective measures can help to confirm or rule-out a diagnosis. Such selective testing is analogous to a medical evaluation in which specific tests are selected by the physician for the individual patient to better confirm or discount a hypothesized diagnosis. Similarly, routine measures may be given to all bariatric surgery candidates but more specific ones (e.g., a screening instrument for alcohol abuse) may also be indicated. For example, differentiating between excessive alcohol use and abuse may be difficult, especially with a guarded patient. Using standardized instruments with norms and clinical cut-offs can help refine the diagnoses. Ideally, a clinical interview and psychological testing are further augmented by collateral informants and review of medical and psychiatric records.

Appropriate Test Selection

As previously discussed, psychological testing can be a highly useful adjunct to the clinical interview. However, not all tests yield the same benefit. Selecting appropriate instruments is critical for gathering as much beneficial information as possible. The following section will review four ideal components of test selections: 1) appropriateness for the candidate, 2) psychometrics of the measure, 3) whether it evaluates distortions in self report, and 4) practicality.

When selecting psychological measures for use in standard pre- and post-surgical evaluation, providers should first ensure that the instrument is appropriate for the population. Measures with bariatric norms are ideal because strengths or weaknesses can be seen in the context of an appropriate comparison group. At a minimum, the measure should have a medical standardization sample rather than only psychiatric norms or norms in the general population. Unfortunately, there are a large number of instruments that have only been normed on college undergraduates with little generalizability to clinical populations.[20] Providers must also determine if the instrument is appropriate for the individual. Many tests have a reading comprehension level that may be beyond the abilities of persons with English as a second language, limited education, or limited reading skills.[5]

Selected measures should also be psychometrically sound. Validated, published instruments should generally be selected over idiosyncratic ones developed by the evaluator. They should have acceptable reliability meaning that the instrument is stable (e.g., the same person will score similarly over time) and consistent (i.e., there is internal consistency of the items). Internal consistency measurements of 0.70 are generally considered adequate for research, while scores closer to 0.90 are considered more appropriate for clinical decision making.[21]

As mentioned above, the measure should be valid. Validity is a more complicated construct but essentially means that the instrument accurately measures what it purports to measure. This can be assessed by determining if it correlates reasonably well with other relevant measures or variables (e.g., a depression measure correlating well with depression diagnoses).[20] Similarly, a measure should not correlate with measures that are theorized to be unrelated to it.[20] Validity can further be determined by a measure discriminating between groups that it should (e.g., binge eaters versus nonbinge eaters) and whether it is responsive to a treatment intervention (e.g., Do scores on a binge eating instrument decline following intervention?). Finally, validity can also be assessed by whether the instrument can prospectively predict outcome.[22] Poor reliability of an instrument can lead to questionable validity as the maximum validity of a test is the square root of the reliability.[23] Reliability and validity are not fixed properties of scales and should be evaluated in each presenting population.[21] For example, an instrument that has good psychometrics for patients with eating disorders may have unacceptable reliability and validity in a bariatric population.

Ideally, instruments should also evaluate for possible distortions in self report. Weight loss surgery candidates are highly aware that psychological assessment is an evaluative process.[13] As previously noted, many individuals may be tempted to present themselves in a more favorable light or conversely may believe that if they report a high level of distress that this may help their candidacy and move them forward more quickly. Other concerns may arise when patients take a haphazard approach to testing (e.g., having a tendency to answer randomly or answer all items in the affirmative). Indicators of whether a profile is truly valid can be invaluable in assessing a patient’s true level of psychosocial functioning.

Finally, the practicality of instruments must be considered. The very best test battery from a diagnostic perspective may be prohibitively expensive or may place too great a burden on the patient or on the provider required to interpret it. Studies have demonstrated widely divergent findings when psychological interviewing and assessment is separate and confidential from the evaluative process.13 However, this process is only feasibly conducted within large research trials.

Commonly Utilized Measures

A number of issues are relevant for psychological testing in bariatric populations. Generally, these are the domains that are of clinical and research interest to bariatric professionals as they are linked with indications/contraindications for surgery, management issues, and outcome. Most commonly, assessments examining general psychopathology, personality traits and disorders, and emotional symptoms are part of routine psychological testing and will be reviewed in depth. More specific assessments may include psychosocial domains, such as depression and anxiety, eating attitudes and behaviors, quality of life, alcohol use, and cognitive function. These will also be briefly discussed. Others may include screening instruments for substance use/abuse, coping styles, motivation, and adherence. Finally, on a more specific case basis, assessment of cognitive capacity and capacity to consent may be included. The following described measures are those most frequently cited in the weight loss surgery literature but in no way should be considered an exhaustive inventory of available instruments. Table 1 outlines commonly utilized instruments, reported frequency of use, reliability and validity estimates, cost, and availability of bariatric norms.

Measures of Psychopathology/Personality. The Symptom Checklist 90 Revised. The Symptom Checklist 90 Revised [SCL-90-R][24] is a brief, commonly used self-report inventory. It consists of 90 items, ranging between 0.0 (never) and 4.0 (extremely), that assess global psychiatric distress, as well as more specific problem areas including depression, anxiety, psychosis, somatic complaints, and interpersonal strain. Between 7 and 8 percent of programs surveyed in 2005 reported use of the SCL-90-R in bariatric psychological evaluations.[2] Although predominantly developed for and used in psychiatric populations, the SCL-90-R has been applied as a descriptive measure of psychopathology, as an outcome measure, and as a screening instrument in several different medical populations.[25,26] Within a bariatric population, Cronbach alpha coefficients range from 0.76 to 0.90.[27] This study also showed convergent validity with other psychiatric history variables.[27] It takes between 15 and 20 minutes to complete. The SCL-90-R, however, has been criticized as being a global measure of distress or dysphoria, with limited discriminant validity.[26] Further, there are no indicators for response set (e.g., faking good).

The Millon Behavioral Medicine Diagnostic (MBMD). The Millon Behavioral Medicine Diagnostic (MBMD) is a 165-item, true/false self-report inventory that takes approximately 20 to 30 minutes to complete.[28] Bariatric norms are available. It yields 29 clinical scales, one validity indicator, six negative health habit indicators (e.g., alcohol, eating, caffeine), 11 coping style scales, six scales of psychiatric indicators believed to create problems with medical treatment (e.g., depression, cognitive dysfunction), five scales of treatment prognostics (e.g., interventional fragility, medication abuse) and two scales of management guidelines (e.g., whether or not individual would benefit from psychological treatment). Approximately one- fourth to one-third of providers conducting bariatric psychological evaluations endorse use of the MBMD.[2,3] The manual includes a set of MBMD algorithms for use with bariatric surgery candidates that reportedly combine to predict early postoperative behaviors. Reliability of scales on the MBMD range from 0.22 to 0.89.[23] Half of the scales do not have internal consistency reliability coefficients that meet minimum standards, which further raises concerns about validity.[23]

The Personality Assessment Inventory (PAI). The Personality Assessment Inventory (PAI)29 is a 344-item scale assessing personality and psychopathology. Items are ranked on a four-point scale and it takes approximately one hour to complete. It is relatively frequently used with 18 percent of clinicians conducting bariatric evaluations endorsing its use.[3] The instrument yields four validity scales, 11 clinical scales (including those for borderline and antisocial personality features and drug and alcohol use/abuse), five treatment scales (e.g., aggression, treatment rejection), and two interpersonal scales (dominance, warmth). Norms for bariatric samples have been offered and it has shown adequate internal consistency for full scales (ranging from 0.53–0.91) within this population.[30] However, alpha coefficients for subscales were more variable (ranging from 0.49–0.84) perhaps reflecting the lower base-rate of these domains (e.g., psychoticism).[30]

The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI-2). The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI-2)[31] is a 567 true/false-item self-report assessment that measures major symptoms of psychopathology, personality and social adjustment. It is an updated version of the original MMPI.[32] It contains eight validity scales, five self-presentation subscales, 10 clinical scales, nine restructured clinical scales, 15 content scales, 27 content component scales, 20 supplementary scales, and 31 clinical subscales. The MMPI-2 is one of the most researched psychological instruments with good reliability and validity in a wide variety of medical populations and test scores have been shown to be associated with weight loss one year after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) surgery.[33] Patients who lost less than 50-percent excess weight scored significantly higher on subscales measuring of somatization and anxiety.[33] It is widely used by mental health professionals assessing bariatric candidates with over 40 percent utilizing the MMPI as part of their evaluative process in 2006.3 However, it is relatively expensive to administer and score. Further, the MMPI-2 takes between 90 and 120 minutes for the patient to complete, so the burden is somewhat considerable, particularly if additional instruments are included.

The MMPI-2- Restructured Form (MMPI-2-RF). The MMPI-2- Restructured Form (MMPI-2-RF)[34] is a 338-item version of the MMPI-2 that consists of nine validity scales and 42 substantive scales that measure broadband, psychological constructs relevant to the assessment of personality and psychopathology. Of the substantive measures, the test consists of three higher-order scales, nine restructured scales, five somatic/cognitive complaint scales, nine internalizing scales, four externalizing scales, five interpersonal scales, two interest scales, and five personality style scales. Subscales include reported difficulties with depression/mood, anxiety and substance use. The nine restructured clinical (RC) scales have good internal consistency (mean Cronbach’s alpha=0.74) and convergent and discriminant validity within a bariatric surgery sample; and has been shown to have better psychometrics than the original MMPI-2 within this population.35 Although briefer than the longer MMPI-2, it still takes approximately 45-60 minutes and is limited by the cost to administer.

Specialized instruments. As previously noted, bariatric mental health professionals may seek more specific information not adequately measured by the global instruments assessing personality and psychopathology. Clinicians use an almost countless number of instruments; however, few have been empirically evaluated in bariatric populations. The following domains of interest will be discussed with a focus on measures that have been studied with bariatric patients: depression and anxiety, eating pathology, quality of life, alcohol use, and cognitive function.

Depression and anxiety. Depression is the most common lifetime psychiatric diagnosis in bariatric surgery patients.[13] As a result, many clinicians choose to assess depression more specifically than with the previously described instruments. The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)[36] is the most commonly used measure for evaluating depressive symptoms in bariatric surgery candidates.[2,4] The BDI is a 21-item, self-report questionnaire assessing depressive symptoms in the last week. Items are scored on a four-point scale with higher score indicative of greater depression. Clinical cut-offs have been developed for minimal, mild, moderate and severe depression.[37] Reliability in bariatric patients have been reported to be quite good (alpha=0.88).[38] The BDI has a number of somatic items, which may artificially inflate scores in bariatric and other medical populations. As a result, some research has suggested using a cut-off point of 12 or higher rather than 10 for mild depression in this population.[38]

Anxiety is also markedly prevalent in this population. Although mood disorders are the most common lifetime diagnosis, anxiety disorders are the most common current diagnosis, effecting approximately 18 percent of bariatric patients.13 Thus, anxiety is often screened with both broad-based measures of psychopathology as well as specific instruments. The Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI)[39] is a 21-item, self-report questionnaire. Like the BDI, clinical cut-offs have been established for minimal, mild, moderate, and severe anxiety and reliability is high.[39] However, like the BDI, there are a number of somatic symptoms that may be inflated in bariatric populations (e.g., sleeping difficulties), which can erroneously inflate total scores.

Eating pathology. Many of the more general measures described previously are limited by a lack of assessment of disordered eating. In recent years, a number of self-report questionnaires initially developed for and validated in eating disordered populations have been utilized to assess eating disordered symptoms in obese patients presenting for weight loss surgery. Although a number are available, norms and psychometrics within this population are often not reported. The Eating Disorders Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q)[40] is the 32-item, self-report version of the EDE with measures of restraint, eating concern, weight concern, and shape concern. It has been validated in bariatric surgery patients and has demonstrated good internal consistency (0.72–0.95) and convergent validity although a somewhat different factor structure.[41] The Binge Eating Scale (BES)[42] consists of 16 items that describe the affective, cognitive, and behavioral aspects of binge eating. The measure has been found to have construct validity in its ability to distinguish between minimal, moderate, and severe binge eating problems. Clinical cut-offs of binge eating severity have been established for the BES[43] and internal consistency has been reported in bariatric populations (Cronbach’s alpha=0.90).[44] Although the previous two instruments have reported psychometrics in a weight loss surgery population, it is vital to confirm diagnosis with a clinical interview as highly divergent prevalence rates are noted depending upon the instrument used.[13] Finally, the Night Eating Questionnaire (NEQ)[45] is a 14-item, five-point Likert scale used to measure the severity of symptoms associated with night eating syndrome. It measures four factors associated with night eating, including nocturnal ingestion, evening hyperphagia, morning anorexia, and mood/sleep). It has adequate internal consistency (alpha=0.70), convergent validity, and has been validated in weight loss surgery candidates.[45]

Quality of life. Quality of life is often examined both pre- and postoperatively to determine the burden of obesity on the patient, the benefits of reduction in weight, and medical comorbidities. The 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36)[46] is a very widely used self-report measure of eight areas of physical and emotional health. Each item is rated on a 10-point Likert scale with higher scores indicative of better quality of life. However, it has not been psychometrically evaluated with bariatric patients. The Impact of Weight on Quality of Life-Lite (IWQOL-Lite)[47] is a 31-item, self-report questionnaire that measures the impact of weight of psychosocial quality of life in individuals with obesity. The IWQOL-Lite shows very good internal consistency and construct validity.[47] A Spanish version of the instrument is also available with very good psychometric properties for bariatric patients.[48]

Substance use. Another potential area of concern within bariatric populations is problematic substance use. Many providers screen during a clinical interview, often following Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition text revision (DSM-IV-TR)[49] criteria and potential cut-offs for problematic use in this population have been described.[50] Additionally, when patients identify drinking above predetermined cut-offs, screening measures may be helpful. A commonly used instrument is the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT).[51] The AUDIT is a measure from the World Health Organization and is designed to screen within medical settings. It can be completed as a self report or in a clinical interview, and a Spanish language version is also available. Although well-validated across numerous medical populations, its use in bariatric populations has yet to be specifically reported.

Cognitive function. Given the importance of determining decisional capacity, informed consent and surgery-related knowledge, providers may want to include a brief screen of cognitive function and/or impairment. This may be especially important when evaluating older candidates.[52] On the most commonly utilized cognitive screens is the Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE).[53] The MMSE is a brief, standardized measure of mental status that is utilized to detect cognitive impairment associated with neurodegenerative disorders. The MMSE is utilized within a clinical interview and assesses orientation to place and time, registration, attention and concentration, recall, language, following a three-step command and visual construction. Neuropsychological consultation and assessment is often beneficial beyond an interview and screening in order to individually tailor recommendations when cognitive deficits are noted.[52]

Conclusions

Psychological evaluation of bariatric surgery candidates should include clinical interviews conducted by mental health professionals with bariatric experience. Additionally, these structured or semi-structured interviews should be augmented by psychometrically sound, objective psychological instruments. These assessments can provide empirically based and comprehensive information—particularly when they have been normed within a bariatric population. Additionally, they can bolster rapport, help individualize treatment recommendations, and better determine whether a patient is presenting him or herself in a forthright manner. Although widely used, the field is limited by a lack of consensus on what best constitutes an appropriate interview and test battery. Most importantly, research is needed to better understand the relationship between these measures and future outcomes.

References

1. Mechanick JI, Kushner RF, Sugarman HJ et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, the Obesity Society, and American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery medical guidelines for clinical practice for the perioperative nutritional, metabolic and nonsurgical support of the bariatric surgery patient. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2009;17 Suppl 1:S1–70, v.

2. Bauchowitz AU, Gonder-Frederick LA, Olbrisch M, et al. Psychosocial evaluation of bariatric surgery candidates: A survey of present practices. Psychosomatic Med. 2005;67:825–832.

3. Fabricatore AN, Crerand CE, Wadden TA, Sarwer DB, et al. How do mental health professionals evaluate candidates for bariatric surgery? Survey results. Obes Surg. 2006;16:567–573.

4. Walfish S, Vance D, Fabricatore AN. Psychological evaluation of bariatric surgery applicants: Procedures and reasons for delay or denial of surgery. Obes Surg. 2007;17:1578–1583.

5. LeMont D, Moorehead MK, Parish M, et al. Suggestions for the pre-surgical psychological assessment of bariatric surgery candidates. Allied Health Science Section ad hoc Behavioral Health Committee 2004. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. http://asmbs.org/2012/06/pre-surgical-psychological-assessment/ Accessed 11/30/12.

6. Peterson CB, Berg KC, Mitchell JA. Assessment of bariatric surgery candidates: structured interviews and self-report measures. In: Mitchell JC, de Zwaan M (eds). Psychosocial Assessment and Treatment of Bariatric Surgery Patients. New York (New York): Routledge Press;2012:37–60.

7. Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, et al. Bariatric surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;292(14):1724-1728.

8. Sjöström L, Marbo K, Sjöström CD, et al. Swedish obese subjects study: Effects of bariatric surgery on mortality in swedish obese subjects. N Eng J Med. 2007;357:741–752.

9. Buchwald H, Oien DM. Metabolic/bariatric surgery worldwide 2008. Obes Surg. 2009;19:1605–1611.

10. Kinzl JF, Schrattenecker M, Traweger C, et al. Psychosocial predictors of weight loss after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2006;16:1609-1614.

11. Livhits M, Mercado C, Yermilov I, et al. Preoperative predictors of weight loss following bariatric surgery: Systematic review. Obes Surg. 2012;22:70–89.

12. Kalarchian MA, Marcus MD, Levine MD, et al. Relationship of psychiatric disorders to 6-month outcomes after gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008;4:544–549.

13. Mitchell JE, Selzer F, Kalarchian MA et al. Psychopathology before surgery in the Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery-3 (LABS-3) psychosocial study. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2012;8:533–541.

14. Kalarchian MA, Marcus MD, Levine, MD et al. Psychiatric disorders among bariatric surgery candidates: A relationship to obesity and functional health status. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:328–334.

15. Semanscin-Doerr D, Windover A, Ashton K, Heinberg LJ. Mood disorders in laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy patients: does it affect early weight loss? Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2010;6:191–206.

16. Ambwani S, Boeka AG, Brown JD, et al. Socially desirable responding by bariatric surgery candidates during psychological assessment. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2011 Jul 18. [Epub ahead of print]

17. Walfish S. Reducing Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory defensiveness: effect of specialized instructions on retest validity in a sample of preoperative bariatric patients. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2007;3:184–188.

18. Bonevski B, Campbell C, Sanson-Fisher RW. The validity and reliability of an interactive computer tobacco and alcohol use survey in general practice. Addict Behav. 2010;35:492–498.

19. Wadden TA, Sarwer, DB. Behavioral assessment of candidates for bariatric surgery: A patient-oriented approach. Obesity. 2006;14:53S–62S.

20. Thompson JK. The (mis)measurement of body image: Ten strategies to improve assessment for applied and research purposes. Body Image. 2004;1:7–14.

21. Streiner, DL. Starting at the beginning: an introduction to coefficient alpha and internal consistency. J Pers Assess. 2003;80:99–103.

22. Streiner DL, Norman GR. Health Measurement Scales: A Practical Guide to Their Construction and Use, fourth edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press;2008:167–210.

23. Walfish S, Wise EA, Streiner DL. Limitations of the Millon Behavioral Medicine Diagnostic (MBMD) with bariatric surgical candidates. Obes Surg. 2008;18:1318–1322.

24. Derogatis LR. SCL-90-R: Administrative Scoring and Procedures Manual. Minneapolis (Minnesota): NCS Pearson;1994.

25. Choung RS, Locke GR, Zinsmeister AR, et al. Psychosocial distress and somatic symptoms in community subjects with irritable bowel syndrome: a psychological component is the rule. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1772–1779.

26. Giel KE, Enck P, Zipfel S, et al. Psychological effects of prevention: do participants of a type 2 diabetes prevention program experience increased mental distress? Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2009;25:83–88.

27. Ransom D, Ashton KR, Windover AK, Heinberg LJ. Internal consistency and va27. Ransom D, Ashton KR, Windover AK, Heinberg LJ. Internal consistency and validity assessment of the SCL-90-R for bariatric surgery candidates. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2010;6:622-627.

28. Millon T, Antoni M, Millon C, et al. MBMD Manual supplement: bariatric report. Minneapolis (Minnesota): NCS Pearson;2007.

29. Morey LC. Personality assessment Inventory Professional Manual Second Edition. Odessa (Texas): Psychological Assessment Resources;2007.

30. Corsica JA, Azarbad L, McGill K, et al. The Personality Assessment Inventory: clinical utility, psychometric properties, and normative data for bariatric surgery candidates. Obes Surg. 2010;20:722–731.

31. Butcher JN, Dahlstrom, WG, Graham, JR, et al. The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 (MMPI-2): Manual for administration and scoring. Minneapolis (Minnesota): University of Minnesota Press;1989.

32. Hathaway, SR, and McKinley, JC. A multiphasic personality schedule (Minnesota): I. Construction of the schedule. Journal of Psychology. 1940;10: 249–254.

33. Tsushima WT, Bridenstine MP, Balfour JF. MMPI-2 scores in the outcome prediction of gastric bypass surgery. Obes Surg. 2004;14:528–532.

34. Ben-Porath YS, Tellegen A. The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 Restructured Form (MMPI-2-RF): Manual for Administration, Scoring, and Interpretation. Minneapolis (Minnesota). University of Minnesota Press; 2008.

35. Wygant, DB, Boutacoff, LI, Arbisi, PA, et al. Examination of the MMPI-2 Restructured Clinical (RC) Scales in a sample of bariatric surgery candidates. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2007;14:197–205

36. Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, et al. An inventory of measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:53–63.

37. Beck AT, Steer RA, Garbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev. 1988;8:77–100.

38. Krukowski RA, Friedman KE, Applegate KL. The utility of the Beck Depression Inventory in a bariatric surgery population. Obes Surg. 2010;20:426–431.

39. Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56:893–897.

40. Fairburn CG, Beglin S. Eating disorder examination questionnaire. In: CG Fairburn (ed.). Cognitive Behavior Therapy and Eating Disorders. New York (New York): Guilford Press;2008:309–314.

41. Hrabosky JI, White MA, Masheb RM, et al. Psychometric evaluation of the Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire for bariatric surgery candidates. Obesity. 2008;16(4):763–769.

42. Gormally J, Black S, Daston S, Rardin D. The assessment of binge eating severity among obese persons. Addict Behav. 1982;7:47–55.

43. Marcus MD, Wing RR, Hopkins J. Obese binge eaters: affect, cognition and response to behavioral weight control. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988; 3:433–439.

44. Ashton K, Drerup M, Windover A, Heinberg LJ. Efficacy of a four-session cognitive behavioral group intervention for binge eating among bariatric surgery candidates. Surg Obes Rel Dis. 2009;5:276–282.

45. Allison KC, Lundgren JD, O’Reardon JP, et al. The Night Eating Questionnaire (NEQ): psychometric properties of a measure of severity of the night eating syndrome. Eat Behav. 2008; 9:62–72.

46. Ware JE, Sherbournce CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selction. Med Care. 1993;30:473-483.

47. Kolotkin RL, Crosby RD. Manual for the Impact of Weight on Quality of Life measure (IWQOL and IWQOL-Lite). Durham (North Carolina):Obesity and Quality of Life Consulting; 2008.

48. Andrés A, Saldaña C, Mesa J, Lecube A. Psychometric evaluation of the IWQOL-Lite (Spanish version) when applied to a sample of obese patients awaiting bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2012;5:802–809.

49. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th Edition Text Revision. Washington, DC. 2000.

50. Heinberg LJ, Ashton K, Coughlin JW. Alcohol and bariatric surgery: a review and suggested recommendations for assessment and management. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2012;8:357–363.

51. Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro, MG. Manual for the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) 2nd Edition. Geneva, Switzerland, World Health Organization, 2001: 1–40.

52. Henrickson HC, Ashton K, Windover AK, Heinberg LJ. Psychological considerations for bariatric surgery in older adults. Obes Surg. 2009;19:211–216.

53. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-Mental State: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198.

Category: Past Articles, Review