The Ultimate Revisional Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass Technique

by Felipe Chaux, MD; Mauricio Franco, MD; and J. Esteban Varela, MD, FACS, FASMBS

Felipe Chaux, MD, Mauricio Franco, MD, and J. Esteban Varela, MD, FACS, FASMBS, are with the Diabetes Surgery Institute and Centro de Cirugia para la Obesidad in Bogota D.C., Colombia. Dr. Varela is also Chairman of Surgery at HCA and Professor of Surgery at the University of Central Florida in Orlando, Florida.

Funding: No funding was provided.

Disclosures: The author report no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

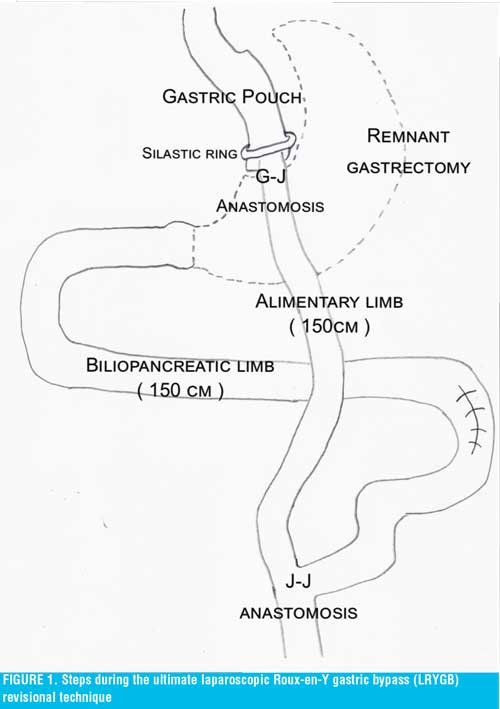

Abstract: We present the technique of the ultimate and complete single-staged revisional laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB) procedure that may correct all potential technical failure sites during reconstruction and prevents future known complications of this revisional surgery. This revisional technique might not only reduce the need for future reoperations and its associated morbidity and mortality but may also be associated with significant healthcare system cost savings.

Keywords: Revisional bariatric surgery, reoperative bariatric surgery, laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, weight regain, weight loss failure

Bariatric Times. 2018;15(2):10–11.

Introduction

Bariatric surgery failure, weight regain, and diabetes recurrence after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB) has led to an increase in the number of revisional bariatric operations performed, which have now become common practice within United States bariatric centers. The mechanisms for weight loss failure and regain appear to be multifactorial; however, failures might be attributed to technical failures at various steps throughout the LRYGB procedure. We describe a stepwise approach and technique of a complete and single-staged revisional LRYGB (i.e., ultimate revision). Five potential failure sites and techniques are addressed during this revisional LRYGB:

- Gastric pouch revision

- Placement of a silastic ring

- Gastro-jejunal anastomosis revision

- Remnant gastrectomy

- Lengthening of the bilio-pancreatic and alimentary limbs to 150cm. This revisional technique might not only reduce the need for future reoperations and its associated morbidity and mortality but might also be associated with significant healthcare system cost savings.

Ultimate LRYGB Revisional Technique

The patient is placed in lithotomy position, and a five-port technique is used. Five potential failure sites and techniques are addressed during a complete single-staged revisional surgery would occur as follows:

Step 1: Gastric pouch revision. An enlarged gastric pouch is a primary cause of LRYGB failure and weight regain. If the pouch is found enlarged during upper endoscopy, upper gastrointestinal (GI) series, or during the revisional procedure, the pouch should be revised by means of a sleeve resection over a bougie, suture plication, or revision of the gastro-jejunostomy. We perform an elongated and narrow gastric tube, dependent on the lesser curvature and preserving the left gastric artery, over a blunt 36Fr bougie with a 4.1mm stapler. All staple lines are reinforced with a running 2-0 nonabsorbable sutures.

Step 2: Placement of silastic ring. During LRYGB reoperations for patients with super obesity (body mass index above 50 kg/m2), we prefer to place a 6.5 by 2.0mm silastic ring just 1–2cm above the gastro-jejunostomy, which leaves a stoma diameter of approximately 12–14mm. The ring is secured to the gastric tube with two interrupted 2-0 nonabsorbable sutures piercing the ring.

Step 3: Gastro-jejunal anastomosis revision. If this anastomosis is found enlarged with a diameter greater than 15mm during upper endoscopy or if a gastric tube has been created, we prefer to remodel the anastomosis with a 3.5mm linear stapler. This anastomosis is closed over the same 36F bougie with 2-0 nonabsorbable running suture and reinforced circumferentially.

Step 4: Remnant gastrectomy. The gastrocolic ligament is divided with bipolar energy device, thereby mobilizing the gastric remnant. After this, the antrum is divided approximately 6cm proximal to the pylorus with a 4.1mm stapler and oversewn with a running 2-0 nonabsorbable suture.

Step 5: Lengthening of the bilio-pancreatic and alimentary limbs. Typical LRYGB present with bilio-pancreatic limbs 30 to 50cm in length. The bilio-pancreatic limb is elongated to 150cm, thereby excluding a greater length of the jejunum. Without needing to take down the three limbs of the jejuno-jejunal anastomosis, the alimentary limb is divided just proximal to the anastomosis with a 2.5mm stapler, and a new bilio-pancreatic limb is measured 150cm from the ligament of Treitz. A new jejuno-jejunal anastomosis is created with a second 2.5mm stapler. This anastomosis is closed and reinforced with a running 2-0 nonabsorbable suture. This reinforcement is performed on the entire anterior surface of the anastomosis where the staple line ends, which might prevent future anastomotic dilation and a potential Jejuno-jejunal intussusception. If the alimentary limb is found to be excessively short (i.e., 50cm), this would need to be resected, and a 150cm new alimentary limb fashioned. Conversely, if the alimentary limb measures approximately 100cm, it may be left intact. The common limb is measured prior to anastomosis to assure that at least 300cm are left in situ.

A methylene blue dye test is performed at the completion of the procedure. All mesenteric defects, including jejuno-jejunal and Peterson’s are closed with running 2-0 nonabsorbable suture. A large 30Fr open four-channel silicone drain system is left nearby the gastro-jejunal anastomosis and exited through the skin.

The postoperative management is similar to a primary LRYGB: a gastrografin study is obtained on postoperative Day 1, and a liquid diet is initiated. Patients are typically discharged on postoperative Day 2 or 3 with the drain in place.

Discussion

The increased use of bariatric procedures worldwide with long-term follow-up has resulted in the growth of revisional or reoperative bariatric surgery to correct weight loss failure or regain after LRYGB, which now has become a common practice. Fortunately for revisional bariatric surgery, the complication rate is low with comparable outcomes to primary procedures.1 Furthermore, the evidence regarding reoperative surgery for failed weight loss and weight regain has demonstrated improved weight loss and comorbidity reduction after reintervention.2 Less than 50 percent of excess weight loss at 18 months is the most frequent definition identified in the literature.3

The most common surgical and correctable reasons for failure and weight regain include enlarged gastric pouch, dilated gastro-jejunal anastomosis, gastro-gastric fistula, and shortened bilio-pancreatic and alimentary limbs. Most of the revisional surgery has focused on specific technical areas, such as resizing the gastric pouch and gastro-jejunal anastomosis or increasing the malabsorptive area by means of lengthening the alimentary limb during typically separate reoperative stages.5–7 In addition, several endoscopic procedures have also been used to resize either the gastric pouch or gastro-jejunostomy with poor results.8,9 Yet, for a large number of patients, revisions of malapsortive technical aspects are addressed one at a time, resulting in several surgeries for each patient. Many of those patients with obesity present for a second or even third revisional bariatric surgery.10

During the ultimate revisional LRYGB, the creation of a small narrow gastric tube not only provides increased restriction to food intake but also increases early satiety via activation of the preserved stretch receptors within the newly created gastric tube. Both the gastric tube and the calibrated gastro-jejunal anastomosis are responsible for the increased restrictive component of this complete revision.

The use of a silastic ring precludes both gastric tube and stoma dilation by diminishing the peristaltic waves originating from the esophagus. In addition, this silastic ring is easily dilated or removed by endoscopic means if needed. We require that patients receiving a silastic ring placement have easy access to an expert bariatric endoscopist. In a recent large cohort study, the use of the silastic ring (Banded GaBP Ring™, Bariatec Corporation, Palos Verdes Peninsula, California) during LRYGB was shown to provide improved long-term weight loss with significantly lower weight regain when compared to non-banded LRYGB.11 A note of caution is that this small ring should be made of silastic material. The use of the commercially available laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (LAP-BAND™, Apollo Endosurgery, San Diego, California) over the gastric tube and anastomosis is strongly discouraged because it might lead to the disastrous complication of gastric tube or anastomotic necrosis and/or erosion. Furthermore, The LAP-BAND™ has no United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for this indication.

Removal of the remnant stomach and fundus not only abolishes residual sources of ghrelin production but also eliminates the potential risk of developing a gastro-gastric fistula in the future. The only downside of this remnant gastrectomy is that it precludes its utilization as a conduit to the biliary tree if needed. A cholecystectomy might also be performed if clinically indicated. The antral stump is left short in order to avoid the rare but potential complication of an antro-pyloric intussusception.

We have previously described the importance of the bilio-pancreatic limb elongation during primary and revisional LRYGB for weight loss, weight regain, and diabetes recurrence.12,13 The elongation of this limb maximizes the incretin effects of the duodenal and jejunal exclusions. It is known that the bilio-pancreatic limb is critical for the malabsorptive, incretin, and anti-incretin mechanisms of the LRYGB (i.e., entero-pancreatic axis theory).14 Although the elongation of the alimentary limb traditionally has been the surgeon’s focus during revisional bariatric surgery, this appears to provide only minimal and transient metabolic and weight loss benefits. If both limbs are elongated to 150cm, this will result in a common limb length of more than 300cm, which does not cause additional nutritional concerns or malabsorptive symptoms. This same length has been advocated as a revisional single anastomosis duodenal switch.

To avoid multiple revisional reoperations, we have focused on the various technical aspects of the LRYGB, which can potentially lead to failure, weight regain, and diabetes recurrence. We believe that all of these should be addressed in a complete, single, and definitive stage revisional surgery. Although, this complete revision LRYGB might seem excessive, the costs of ongoing weight regain, recurring diabetes, multiple reoperations, and associated morbidity and mortality might be avoided. Furthermore, most of the revisional bariatric operations are currently not covered by many insurers. Hence, we favor the complete single-staged revisional LRYGB as our revisional procedure of choice.

This revisional technique is suited for either failed primary LRYGB procedures or conversions from LAP-BAND™ and laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG). The latter, which has increased in popularity in the United States, has now surpassed LRYGB as a primary bariatric procedure.15 It is plausible that in the near future, a number of LSG will be converted to LRYGB or duodenal switch for weight loss failure, weight regain, intractable gastro-esophageal reflux, or diabetes recurrence. LRYGB continues to be the “gold standard” to which all other bariatric procedures are compared.

In conclusion, we present a complete single-staged revisional LRYGB procedure that, in our view, corrects all potential technical failure sites and prevents future known complications of revisional surgery. We believe that this complete revision is feasible and should be part of the bariatric surgeon’s armamentarium. This complete revision does not appear to add significant additional morbidity to an already complex operation. We hypothesize that this approach might not only reduce the need for future reoperations and associated morbidity and mortality, but it also might be associated with significant healthcare system cost savings. Prospective studies evaluating the clinical and economic impact of the complete revisional LRYGB surgery are warranted.

References

- Sudan R, Nguyen NT, Hutter MM, et al. Morbidity, mortality, and weight loss outcomes after reoperative bariatric surgery in the USA. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19(1):171–178; discussion 178–179.

- Brethauer SA, Kothari S, Sudan R, et al. Systematic review on reoperative bariatric surgery: American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Revision Task Force. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10(5):952–972.

- Mann JP, Jakes AD, Hayden JD, Barth JH. Systematic review of definitions of failure in revisional bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2015;25(3):571–574.

- Nguyen D, Dip F, Huaco JA, et al. Outcomes of revisional treatment modalities in non-complicated Roux-en-Y gastric bypass patients with weight regain. Obes Surg. 2015.

- Leon F, Maiz C, Daroch D, et al. Laparoscopic hand-sewn revisional gastrojejunal plication for weight loss failure after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2015.

- Al-Bader I, Khoursheed M, Al Sharaf K, et al. Revisional laparoscopic gastric pouch resizing for inadequate weight loss after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2015.

- Hamdi A, Julien C, Brown P, et al. Midterm outcomes of revisional surgery for gastric pouch and gastrojejunal anastomotic enlargement in patients with weight regain after gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Obes Surg. 2014;24(8):1386–1390.

- Eid GM, McCloskey CA, Eagleton JK, et al. StomaphyX vs a sham procedure for revisional surgery to reduce regained weight in Roux-en-Y gastric bypass patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2014;149(4):372–379.

- Goyal V, Holover S, Garber S. Gastric pouch reduction using StomaphyX in post Roux-en-Y gastric bypass patients does not result in sustained weight loss: a retrospective analysis. Surg Endosc. 2013;27(9):3417–3420.

- Daigle CR, Aminian A, Romero-Talamas H, et al. Outcomes of a third bariatric procedure for inadequate weight loss. JSLS. 2014;18(3).

- Lemmens L. Banded gastric bypass: better long-term results? A cohort study with minimum 5-year follow-up. Obes Surg. 2016.

- Chaux F, Franco M, Varela JE. Metabolic surgery provides remission of pancreatogenic diabetes in a non-obese patient. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12(3):e25–26.

- Chaux F, Bolanos E, Varela JE. Lengthening of the biliopancreatic limb is a key step during revisional Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for weight regain and diabetes recurrence. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2015;11(6):1411.

- Kamvissi V, Salerno A, Bornstein SR, et al. Incretins or anti- incretins? A new model for the “entero-pancreatic axis”. Horm Metab Res. 2015;47(1):84–87.

- Varela JE, Nguyen NT. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy leads the U.S. utilization of bariatric surgery at academic medical centers. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2015.

Category: Past Articles, Review