Managing Substance Use Issues Before and After Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery

by Stephanie Sogg, PhD

Dr. Sogg is with the Massachusetts General Hospital Weight Center and Harvard University Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts.

Funding: No funding was provided for this article.

Disclosures: The author has no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Bariatric Times. 2022;19(8):8–11.

Abstract

Little formal guidance exists to guide metabolic and bariatric surgery (MBS) providers in matters related to substance use, misuse, or disorders, either before or after surgery. This article outlines substance-related concerns relevant at varying points throughout the MBS process and provides information and recommendations to help MBS team members manage substance-related issues in their clinical practice.

Keywords: Bariatric surgery, alcohol, substance, addiction, substance use disorder, gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy

Patient issues related to substance use and misuse can be challenging for members of the metabolic and bariatric surgery (MBS) team at all stages of the MBS treatment process. Most published MBS guidelines cite active substance use disorder (SUD) as a contraindication for surgery.1,2 However, with some notable exceptions,3–5 there is little formal or concrete guidance to assist MBS providers in assessing substance-related issues before surgery, formulating treatment recommendations when concerns about substance use are present in patients seeking MBS, or screening and providing appropriate intervention for substance-related issues when they are present after surgery. This article is intended to extend the published literature with information and recommendations to help MBS team members manage substance-related issues confidently and effectively. It should be noted that one substance, cannabis, is causing a certain degree of consternation among MBS teams,6 who tend to feel at a loss to know how to view and manage the use of this substance, given the varying legal status of medical and/or recreational cannabis use across jurisdictions, a dearth of research regarding cannabis use as it pertains to MBS outcomes, and difficulty quantifying cannabis use, given the multiple modes of delivery and a lack of standardization of the active drug within varying compounds. For these same reasons, cannabis will not be specifically reviewed in this paper. Much of the general guidance pertaining to other substances of abuse in this paper remains relevant to cannabis; for more specific guidance regarding cannabis and MBS, the reader is directed to several excellent manuscripts published elsewhere for background and guidance.5–13

There are a number of reasons for the designation of an active SUD as a contraindication for MBS. In addition, even in cases in which there is frequent and/or concerning substance use, but the patient does not meet diagnostic criteria for a SUD, there are pertinent concerns. Concerns related to problematic substance use and MBS are relevant to all stages of the MBS timeline, starting with preoperative assessment and extending through the long-term postoperative period.

Pre- and Perioperative Considerations

In the preoperative stage, we would expect problematic substance use to have a substantial impact on the patient’s psychosocial and psychiatric stability. We may have concerns about the ways in which problematic substance use could impair the patient’s ability to make sound decisions, including a major decision, such as the choice to pursue MBS. Additionally, a patient with problematic substance use would likely be impeded in their ability to fully engage in the process of becoming prepared for MBS, which requires gathering information about MBS, attending clinic visits, and making behavioral changes. In addition, during the perioperative period, the current (or very recent) concerning use of alcohol and/or other substances of abuse might increase the likelihood of intraoperative complications or adverse outcomes in the short-term after surgery.14,15

Preoperative assessment. The initial evaluation for MBS should include a screening and history-taking, not just for current substance use, but also for any history of past substance use and SUD.16,17 In addition, it is advisable to assess for any genetic history of addiction, because a family history of SUD has been shown in at least one study to be associated with post-MBS alcohol problems (about which see more below).18 While the behavioral health member of the team is likely the provider with the most appropriate expertise and training to assess this domain, some MBS programs have limited behavioral health resources, and other team members might need to complete this portion of the assessment. Even for programs who do have in-house behavioral health resources, it might be desirable for more than one member of the team to take such a history, since patients might at times report different information to different providers.

This substance use assessment may begin with obtaining information about the current quantity and frequency of a patient’s substance use. For instance, regarding alcohol consumption, it is helpful to ascertain not just how often the patient consumes alcohol, but also how much alcohol is consumed on a typical occasion when they are drinking, and whether (and how often) there are any occasions on which the patient consumes a particularly large amount of alcohol.19 The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-Concise (AUDIT-C)20 standardizes this assessment in three simple, quantitative items. When assessing for illicit drug use or use of prescribed drugs in a manner other than how they were prescribed, frequency might be easier and more important to assess than quantity.

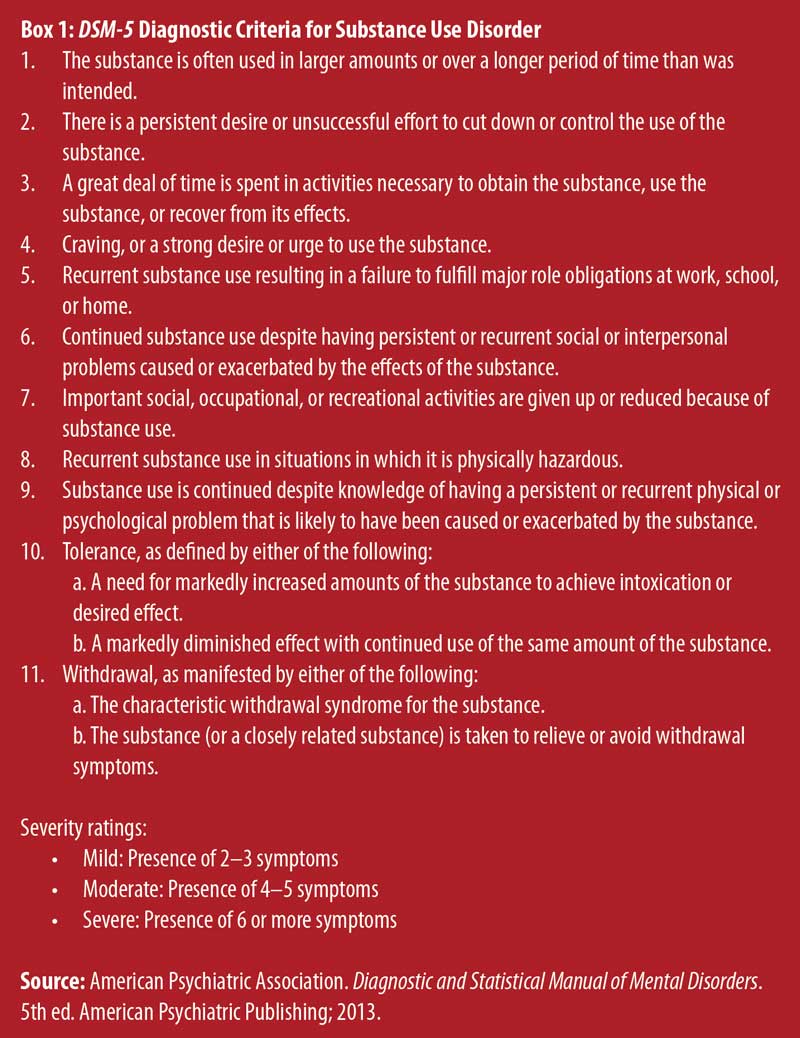

It is important to note here that information regarding the quantity and frequency of substance use is conceptually and diagnostically distinct from the presence or absence of a SUD, and the diagnosis of a SUD is not based on quantity and frequency of use. Rather, the diagnosis of a SUD entails both an inability on the patient’s part to control or limit their use of the substance and the presence of significant consequences to the patient’s functioning, relationships, health, or wellbeing as a result of their substance use.21 Thus, for example, if a patient reports drinking four glasses of wine daily, this information is not sufficient to conclude that the patient has an alcohol use disorder (AUD). Further assessment is needed to determine whether an AUD is present. The diagnostic criteria for SUD are listed in Box 1. It is recommended that the provider evaluate for both current and past symptoms of SUD. If a detailed substance history is not feasible in the time allotted for evaluation, screening instruments may be used. The purpose of a screening instrument is not to diagnose a SUD, but to identify indications of a potential problem and the need for more detailed assessment. Such instruments include the CAGE (the name of this measure is an acronym, with each letter representing a brief form of the content of each of its 4 questions: “Cut Down,” “Annoyed,” “Guilty,” and “Eye-opener”)22 or the full-length version of the AUDIT,23 which assess for potential AUD, and the Tobacco, Alcohol, Prescription Medication, and other Substance Use Tool (TAPS),24 which assesses for both potential AUD and potential drug use disorder. If a patient scores above the established threshold on a SUD screening instrument, the MBS team might want to consider referring the patient for a more thorough and specialized SUD evaluation.

Preoperative recommendations. When a patient endorses current and/or past substance use that raises concerns of SUD, MBS providers might be unsure as to the most appropriate recommendations and treatment plan. No specific formal guidelines have been established to inform practice, and protocols and policies vary from program to program. For instance, authors from the Cleveland Clinic described a protocol whereby patients pursuing MBS are screened for current and past substance issues and categorized as low-, moderate-, or high-risk.3 All preoperative MBS patients receive education about the risks of alcohol misuse following surgery, and additional measures are taken with patients in the moderate- or high-risk categories, including specialized informed consent about MBS and substances and behavioral contracts.3 Authors from the same institution have also suggested steps that can be taken in the MBS treatment of patients who are being treated with opioid medications for pain or who are being treated pharmacologically for opioid use disorder (e.g., with methadone).4 The following suggestions incorporate and expand upon existing resources in the literature and are intended to help to guide MBS clinicians in treatment planning in various scenarios in which there are substance-related concerns.

In instances in which a patient reports a remote history of substance misuse or SUD which has remained in remission, there is no empirical evidence suggesting that this should represent a contraindication for MBS.2,16 The literature on relapse of drug or alcohol use after MBS in individuals with well-established sobriety is sparse, and it is yet unclear whether MBS poses a significant risk for relapse. Additionally, individuals who have successfully recovered from a SUD have, de facto, demonstrated they are capable of making and maintaining a substantial, difficult behavior change; sustained behavior change is necessary for optimal long-term MBS outcomes, so in this regard, a history of successful recovery from SUD might actually be seen as a positive prognosticator.25,26

However, special consideration must be paid to patients with a history of opioid use disorder (and perhaps disorders involving other drugs, as well). Use of opioids for postoperative pain management is common, and no research, to our knowledge, has examined whether there is an elevated risk for relapse of a previously remitted opioid use disorder after MBS. Thus, careful thought must be given to the appropriate perioperative pain management plan.4 It is suggested to consult the patient as to their own preferences in this matter; some patients opt to avoid any opioid medication altogether, while others feel safe with limited perioperative use for pain management, with support from people such as their healthcare providers or a sponsor. If the MBS provider is in doubt as to the most appropriate plan, it can be helpful to consult pain or addiction specialists for their input. Given that there is no empirical data to substantively guide the specifics of the postoperative pain management plan in patients with a history of SUD, it would seem that the nature of the plan may be left to the discretion of the patient and providers, but it is recommended that this plan be detailed and structured and to ensure that this plan is prominently documented in the patient’s chart so that all medical personnel involved in the perioperative treatment of the patient are aware of it.

A more challenging scenario is an instance in which the patient reports recently remitted (i.e., within the past year) problematic substance use/misuse or SUD. It is well-established that early sobriety is fairly tenuous,27 and the MBS program might find it prudent to require a certain period of continued sobriety before moving forward with surgery. The American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) position statement on alcohol use before and after bariatric surgery recommends establishing “a period of sustained abstinence” before proceeding with surgery,2 but the duration of this period is not specified. A period of one year is required by many bariatric programs,2 and this is consistent with the empirical literature, which shows that, for both drugs and alcohol, once an individual has maintained sobriety for one year, the odds of relapse are significantly reduced.28 This information might also inform treatment decisions in cases in which the patient endorses current problematic substance use/misuse or SUD. In any case that raises concerns about substance misuse or SUD, the MBS practice may refer the patient for SUD assessment and/or treatment17 and set a requirement that the patient achieve abstinence and maintain sobriety for a period of time (e.g., one year) before progressing to surgery.3 Recommendations for treatment, as well as notes about adherence to and outcomes of such treatment, and follow-up assessment of the patient’s current status with regard to substance use should be documented in the patient’s chart.

The most challenging situations are those in which the MBS team has reason to be concerned that substance-related issues are present (or were recently present), but the patient denies such problems. When the patient denies current substance-related issues, it is difficult to make a case for mandatory SUD treatment. At such times, it might be helpful to obtain additional information from other sources. For instance, the team might request a release to speak to the patient’s primary healthcare provider or outside behavioral health provider (when there is one), or even a member of the patient’s social support network. They might also conduct a search of the patient’s home state’s prescription drug monitoring program database. In cases that are particularly unclear, and/or when the patient is considered to be at high risk for substance misuse, the team might choose to obtain toxicology screens for drug and/or alcohol use.3 However, it is important to note that this type of action is not without some costs. This type of measure conveys a lack of trust in the patient’s report, which might damage the working alliance between the patient and the members of the MBS team, which, in turn, can further impede patient candor. Ultimately, there is no guaranteed method of ensuring that the patient is reporting truthfully about substance use; thus, what is left for the MBS team is to proceed according to the best of their reasonable knowledge and judgment, taking care to fully and clearly document that they have a reasonable belief that the patient is not engaging in problematic substance use.

Postoperative Considerations

There are also a number of considerations and concerns relating to the longer-term period after MBS. One pressing concern is the fact that there is a heightened risk of substance misuse or SUD after MBS. Alcohol is the substance most well-studied in this regard.29,30 High rates of post-MBS alcohol misuse or AUD have been found in a number of studies.29–39 In addition, for reasons that are not yet clearly understood, there is a risk among some patients without any history of addiction issues to develop such problems after surgery;9,40 rates of new-onset alcohol misuse or AUD have been found to range between 1 to 28 percent in various investigations, with rates in many of the larger and more rigorous studies falling in the range of 6 to 8 percent.18 Post-MBS alcohol problems have been found to occur at a significant latency after surgery; the period of higher risk for onset seems to begin at least two years after MBS,30 though in some studies, the risk of onset has been observed within the first postoperative year.33 The mechanisms underlying this increased risk of alcohol-related problems after MBS have not been fully elucidated, but one factor almost certainly implicated is a change in the impact of alcohol after MBS. The pharmacokinetics of alcohol are significantly altered after both Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB)41 and sleeve gastrectomy (SG).42 After these procedures (but not after laparoscopic gastric banding), blood alcohol levels rise much more rapidly and to a much higher peak than in individuals who have not undergone MBS, which theoretically could result in alcohol being more likely to be abused after surgery.43

In addition, although there is almost no published data regarding rates of opioid use disorder among post-MBS patients, there is increasingly robust evidence that the prevalence of chronic use of prescribed opioids increases after surgery in general,44 and after MBS in particular.4,45–47 This finding is surprising, given that one would expect that the significant weight loss resulting from MBS would likely lead to a decrease in pain, and thus a decrease in the need for pain medication. While the mechanisms underlying the increase in rates of chronic use of prescribed opioids after MBS are not well understood, some risk factors have been identified, including having public (vs. private) insurance, higher levels of pain before surgery and/or less improvement or worsening of pain after MBS, undergoing an additional MBS or orthopedic procedure, initiating or continuing use of other types of analgesics after MBS, ongoing use of benzodiazepines (vs. no use or discontinuation of these medicines), and, counterintuitively, improved mental health after MBS.45 In recent years, enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols, designed to improve perioperative outcomes, have been developed and implemented for MBS. Guidance within such protocols includes minimizing and providing alternatives to opioid use for postoperative pain, and research has demonstrated a positive impact of these protocols on postoperative opioid use after MBS.48–50

There is almost no published literature regarding problems with other types of drugs after MBS.30,51–53 The etiology of addiction-related problems after MBS is not fully understood, but it is likely to be strongly related to physiological mechanisms,18 perhaps coupled with psychosocial stress and a lack of healthy coping strategies.54 Very little is known about predictors of post-MBS substance issues, but a few risk factors have been identified. Patients who were frequent and/or heavy users of alcohol or recreational drugs at the time of surgery (as assessed using measures such as the AUDIT) are at heightened risk to experience increased or problematic use of alcohol or AUD after surgery, as are younger patients, male patients, and those with a family history of SUD.18

For obvious reasons, problematic substance use raises concerns for any individual’s general safety and wellbeing. However, when such problems arise, continue, or recur after MBS, there are additional specific concerns. One area of concern is the impact that substance use and/or the attendant symptoms of SUD might have on the patient’s postoperative adherence. Substance-related issues might interfere with attendance at postoperative appointments with members of the MBS team, surgical support group, or other healthcare-related visits. There might also be an impact on the patient’s ability to maintain adherence to adequate hydration practices or recommended vitamin and supplement regimens. In addition, problematic post-MBS substance use might affect weight outcomes. This impact can occur through direct pathways, for instance, due to additional calorie intake if the patient is consuming alcohol heavily or increased snacking if frequent cannabis use promotes an increase in appetite. It might also affect weight outcomes indirectly by making it more difficult for patients to choose healthier foods, engage in effective meal/snack planning and preparation, limit portion sizes, and participate in consistent physical activity. In addition, the substance use itself and/or its impact on the patient’s self-care or weight loss might have an adverse impact on the health-related outcomes of MBS, such as control of blood pressure or blood glucose, sleep apnea, and other medical conditions relevant to the MBS population.

Postoperative screening and management. Given both the elevated risk of addiction issues after MBS and the clear and significant dangers of such problems, combined with a dearth of empirically established risk factors or predictors, careful education and monitoring are imperative both before and after surgery. Because some postsurgical addiction cases occur in patients with no such history before surgery, all patients undergoing MBS should receive preoperative education about the risk of post-MBS substance issues, even if they have not experienced such issues in the past, including the risk of increased use of prescribed opioid medications, particularly among patients who are treated with these medications for pain before surgery,4 and instructed to be watchful for early warning signs of substance misuse.3,4,17,19 Patients should be encouraged to monitor the quantity and frequency of alcohol use and the onset or increase of any recreational drug use or misuse of prescribed drugs in the long-term after surgery. It is also important to educate all patients who will be undergoing MBS about the changes in alcohol absorption/metabolism that have been found to occur after surgery, and this education should be refreshed repeatedly throughout the postoperative period as well.17 This type of education, while necessary for all MBS patients, is particularly crucial for patients at elevated risk for post-MBS substance-related issues; such patients might benefit from more intensive education before surgery. For example, the Cleveland Clinic has developed a 90-minute intervention providing education about the health effects of alcohol/substances after MBS, warning signs of substance-related problems, and guidance on developing alternative coping strategies and resources for treatment.55

Screening for substance-related problems should be conducted in all patients following MBS and continuing into the long-term postsurgical period.17,19 Such screenings can be implemented in a manner similar to the procedures noted above for presurgical assessment, with some additions and adaptations. For instance, in addition to simply assessing current quantity and frequency of substance use in postoperative patients, current use should be compared to quantity and frequency of use before surgery, since an increase in substance use from pre- to postsurgery might be a red flag, even if the level of current use would not be particularly concerning in and of itself. When assessing use of alcohol in patients who have undergone MBS, it is important to bear in mind that, as noted above, the pharmacokinetics of alcohol are significantly altered after both RYGB41 and SG.42 Thus, while a pattern of consuming 2 to 3 drinks per occasion might not seem particularly worrisome in an individual who has not had MBS, this amount of alcohol would have a much more intense impact on someone who has had MBS. When assessing substance use in patients who have undergone MBS, it is also important to examine the impact of the substance use both on the patient’s general health and wellbeing, as well as on the patient’s adherence to the post-MBS regimen and their weight outcome. In addition to asking screening questions about quantity, frequency, and impact of drug and alcohol use, clinicians might also want to briefly screen for the presence of so-called behavioral addictions, as there are reports, albeit infrequent, of patients who have undergone MBS developing compulsive behaviors around gambling, shopping, shoplifting, and sexual activity.56

To date, there has been no published research examining specialized treatment for addictions that arise after MBS. It is not clear whether patients who have undergone MBS require addiction treatment that is different from the types of interventions that have already been established to be effective for treating addictions in general (e.g., cognitive-behavioral therapy, 12-step programs, pharmacological interventions). In the absence of specialized addiction treatment programs for patients who have undergone MBS, the most appropriate current recommendation would be for MBS practices to develop and maintain a database of local addiction clinicians/facilities to assist in expedient referral for evaluation and treatment of substance-related problems.

However, a further step is indicated to ensure the effective and timely identification of patients who have developed substance-related problems after MBS. Given the fact that such problems do not tend to arise until approximately two years after surgery, patients might not be still closely engaged with their MBS programs at the time when these issues are most likely to begin. Therefore, it is incumbent on the members of the MBS field to actively seek to educate healthcare providers in other specialties who are more likely to be interacting with their patients at this time of higher risk. This would be particularly relevant for certain specialties, such as primary care/internal medicine, endocrinology, cardiology, behavioral health, and any other specialty discipline in which many patients are likely to have or have had obesity. This might be one of the most effective avenues currently available to enhance prevention and early detection of post-MBS substance-related problems. All MBS providers are encouraged to educate colleagues in other disciplines to help them look after our patients after they have left the MBS practice.

Conclusion

Problematic substance use is of significant concern before and after MBS. Thorough screening is recommended for patients seeking MBS, as well as at regular intervals throughout the long-term after MBS. In addition, it is crucial to educate all patients who are seeking to undergo or who have undergone MBS about the risks of substance-related problems after surgery and to ensure that healthcare providers of other disciplines are aware of these risks, so that they, too, can be monitoring for such problems.

References

- Mechanick JI, Apovian C, Brethauer S, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the perioperative nutrition, metabolic, and nonsurgical support of patients undergoing bariatric procedures–2019 update: cosponsored by American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology, The Obesity Society, American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery, Obesity Medicine Association, and American Society of Anesthesiologists. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2020;16(2):175–247.

- Parikh M, Johnson JM, Ballem N. ASMBS position statement on alcohol use before and after bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12(2):225–230.

- Heinberg LJ, Ashton K, Coughlin J. Alcohol and bariatric surgery: review and suggested recommendations for assessment and management. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2012;8(3):357–363.

- Heinberg LJ, Pudalov L, Alameddin H, Steffen K. Opioids and bariatric surgery: a review and suggested recommendations for assessment and risk reduction. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2019;15(2):314–321.

- Rummell C, Heinberg L. Assessing marijuana use in bariatric surgery candidates: should it be a contraindication? Obes Surg. 2014;24(10):1764–1770.

- Diggins A, Heinberg L. Marijuana and bariatric surgery. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2021;23(2):10.

- Vidot DC, Deo S, Daunert S, et al. A preliminary study on the influence of cannabis and opioid use on weight loss and mental health biomarkers post-weight loss surgery. Obes Surg. 2020;30(11):4331–4338.

- Bauer F, Donohoo W, Tsai A, et al. Marijuana use and outcomes in the bariatric population. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12:s123.

- Vidot DC, Prado G, De La Cruz-Munoz N, et al. Postoperative marijuana use and disordered eating among bariatric surgery patients. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12(1):171–178.

- Bauer FL, Donahoo WT, Hollis HW, Jr., et al. Marijuana’s influence on pain scores, initial weight loss, and other bariatric surgical outcomes. Perm J. 2018;22:18-002.

- Huson HB, Granados TM, Rasko Y. Surgical considerations of marijuana use in elective procedures. Heliyon. 2018;4(9):e00779.

- Shockcor N, Adnan SM, Siegel A, et al. Marijuana use does not affect the outcomes of bariatric surgery. Surg Endosc. 2021;35(3):1264–1268.

- Worrest T, Malibiran CC, Welshans J, et al Marijuana use does not affect weight loss or complication rate after bariatric surgery. Surg Endosc. In Press.

- Moran S, Isa J, Steinemann S. Perioperative management in the patient with substance abuse. Surg Clin North Am. 2015;95(2):417–428.

- Tonnesen H, Kehlet H. Preoperative alcoholism and postoperative morbidity. Br J Surg. 1999;86(7):869–874.

- Sogg S, Lauretti J, West-Smith L. Recommendations for the presurgical psychosocial evaluation of bariatric surgery patients. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12(4):731–749.

- Kanji S, Wong E, Akioyamen L, et al. Exploring pre-surgery and post-surgery substance use disorder and alcohol use disorder in bariatric surgery: a qualitative scoping review. Int J Obes (Lond). 2019;43:1659–1674.

- Ivezaj V, Benoit SC, Davis J, et al. Changes in alcohol use after metabolic and bariatric surgery: predictors and mechanisms. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21(9):85.

- Haskins IN. Comment on: emergency department encounters, hospital admissions, course of treatment, and follow-up care for behavioral health concerns in patients after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2021;17(10):e50–e51.

- Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, et al. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(16):1789–1795.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

- Mayfield D, McLeod G, Hall P. The CAGE questionnaire: validation of a new alcoholism screening instrument. Am J Psychiatry. 1974;131(10):1121–1123.

- Bohan Brown MM. Digging into breakfast: serving up a better understanding of the effects on health of the “most important meal of the day.” Am J Clin Nutr. 2019;110(1):4–5.

- McNeely J, Wu L-T, Subramaniam G, S et al. Performance of the Tobacco, Alcohol, Prescription Medication, and Other Substance Use (TAPS) tool for substance use screening in primary care patients. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(10):690–699.

- Clark MM, Balsiger BM, Sletten CD, et al. Psychosocial factors and 2-year outcome following bariatric surgery for weight loss. Obes Surg. 2003;13(5):739–745.

- Heinberg L, Ashton K. History of substance abuse relates to improved postbariatric body mass index outcomes. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2010;6(4):417–421.

- de Bruijn C, van den Brink W, de Graaf R, Vollebergh WAM. The three year course of alcohol use disorders in the general population: DSM-IV, ICD-10 and the Craving Withdrawal Model. Addiction. 2006;101(3):385–392.

- Hunt WA, Barnett LW, Branch LG. Relapse rates in addiction programs. J Clin Psychol. 1971;27(4):455–456.

- King W, Chen J, Mitchell J, et al. Prevalence of alcohol use disorders before and after bariatric surgery. JAMA. 2012;307(23):2516–2525.

- King WC, Chen J-Y, Courcoulas AP, et al. Alcohol and other substance use after bariatric surgery: prospective evidence from a US multicenter cohort study. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13(8):1392–1402.

- Azam H, Shahrestani S, Phan K. Alcohol use disorders before and after bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Trans Med. 2018;6(8):148.

- Backman O, Stockeld D, Rasmussen F, et al. Alcohol and substance abuse, depression and suicide attempts after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Br J Surg. 2016;103(10):1336–1342.

- Bramming M, Becker U, Jorgensen MB, et al. Bariatric surgery and risk of alcohol use disorder: a register-based cohort study. Int J Epidemiol. 2021;49(6):1826–1835.

- Ibrahim N, Alameddine M, Brennan J, et al. New onset alcohol use disorder following bariatric surgery. Surg Endosc. 2019;33(8):2521–2530.

- Ostlund MP, Backman O, Marsk R, et al. Increased admission for alcohol dependence after gastric bypass surgery compared with restrictive bariatric surgery. JAMA Surg. 2013;148(4):374–377.

- Smith KE, Engel SG, Steffen KJ, et al. Problematic alcohol use and associated characteristics following bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2018;28(5):1248–1854.

- Spadola CE, Wagner EF, Dillon FR, et al. Alcohol and drug use among postoperative bariatric patients: a systematic review of the emerging research and its implications. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2015;39(9):1582–1601.

- Steffen KJ, Engel SG, Wonderlich JA, et al. Alcohol and other addictive disorders following bariatric surgery: prevalence, risk factors and possible etiologies. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2015;23(6):442–450.

- Svensson P-A, Anveden Å, Romeo S, et al. Alcohol consumption and alcohol problems after bariatric surgery in the swedish obese subjects study. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2013;21(12):2444–4451.

- Wiedemann AA, Saules KK, Ivezaj V. Emergence of new onset substance use disorders among post-weight loss surgery patients. Clin Obes. 2013;3(6):194–201.

- Pepino MY, Okunade AL, Eagon JC, et al. Effect of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery: converting 2 alcoholic drinks to 4. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(11):1096–1098.

- Acevedo MB, Eagon JC, Bartholow BD, et al. Sleeve gastrectomy surgery: when 2 alcoholic drinks are converted to 4. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018;14(3):277–283.

- Gossop M, Marsden J, Stewart D, Kidd T. The National Treatment Outcome Research Study (NTORS): 4-5 year follow-up results. Addiction. 2003;98(3):291–303.

- Brummett CM, Waljee JF, Goesling J, et al. New persistent opioid use after minor and major surgical procedures in US adults. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(6):e170504.

- King WC, Chen J-Y, Belle SH, et al. Use of prescribed opioids before and after bariatric surgery: prospective evidence from a US multicenter cohort study. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13(8):1337–1346.

- Raebel MA, Newcomer SR, Bayliss EA, et al. Chronic opioid use emerging after bariatric surgery. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2014;23(12):1247–1257.

- Raebel MA, Newcomer SR, Reifler LM, et al. Chronic use of opioid medications before and after bariatric surgery. JAMA. 2013;310(13):1369–1376.

- Ma P, Lloyd A, McGrath M, et al. Reduction of opioid use after implementation of enhanced recovery after bariatric surgery (ERABS). Surg Endosc. 2020;34(5):2184–2190.

- Monte SV, Rafi E, Cantie S, et al. Reduction in opiate use, pain, nausea, and length of stay after implementation of a bariatric enhanced recovery after surgery protocol. Obes Surg. 2021;31(7):2896–2905.

- King AB, Spann MD, Jablonski P, et al. An enhanced recovery program for bariatric surgical patients significantly reduces perioperative opioid consumption and postoperative nausea. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018;14(6):849–856.

- Conason A, Teixeira J, Hsu CH, et al. Substance use following bariatric weight loss surgery. JAMA Surg. 2013;148(2):145–150.

- Reslan S, Saules KK, Greenwald MK, Schuh LM. Substance misuse following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Subst Use Misuse. 2014;49(4):405–417.

- Saules K, Ashley W, A, Ivezaj V, et al. Bariatric surgery history among substance abuse treatment patients: prevalence and associated features. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2010;6(6):615–621.

- Yoder R, MacNeela P, Conway R, Heary C. How do individuals develop alcohol use disorder after bariatric surgery? A grounded theory exploration. Obes Surg. 2018;28(3):717–724.

- Ashton K, Heinberg L, Merrell J, et al. Pilot evaluation of a substance abuse prevention group intervention for at-risk bariatric surgery candidates. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2013;9(3):462–467.

- Bak M, Seibold-Simpson SM, Darling R. The potential for cross-addiction in post-bariatric surgery patients: considerations for primary care nurse practitioners. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2016;28(12):675–682.

Category: Past Articles, Review

I found it interesting when you said that the intervention process would be the next procedure after the screening. The other day, a friend of mine told me he was hoping to have a treatment consultation to be enlightened as his brother has pilot substance abuse issues due to past traumas. He asked me if I had any idea what would be s the best option to resolve it. Thanks to this instructive article, I’ll tell him that it will be much better if he consults trusted anxiety and depression counseling as they can provide the best treatment for his brother.