Improving Adherence to Micronutrient Supplementation in the Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Patient Population

This activity expired May 26, 2020.

Course Overview: The improved health outcomes of metabolic and bariatric surgery are undeniable, however, the high frequency of micronutrient deficiencies, especially those that are under-recognized and left untreated, can lead to irreversible consequences. This article discusses barriers to adherence, common known clinical manifestations of micronutrient deficiency, and strategies for improving patient adherence, including clinician familiarity with available professional guidelines for micronutrient supplementation in the metabolic and bariatric surgery patient population.

Course Description: This educational program is designed to educate, through independent study, multidisciplinary clinicians who care for the metabolic and bariatric surgery patient population.

Course Objectives: Upon completion of this program, the participant should be able to:

- List known barriers to micronutrient supplementation adherence in the metabolic and bariatric surgery patient population

- Identify the most prevalent micronutrient deficiencies in metabolic and bariatric surgery patients, including examples of accompanying

physical signs and symptoms - Discuss available professional guidelines for micronutrient supplementation in the metabolic and bariatric surgery patient

population - Discuss strategies for improving patient adherence to micronutrient supplementation.

Target Audience: This accredited program is intended for multidisciplinary clinicians who treat patients with obesity.

Provider: This educational program is provided by Matrix Medical Communications. Provider approved by the California Board of Registered Nursing, Provider Number 14887, for 1.0 contact hour. This educational activity is approved by the Commission on Dietetic Registration, the credentialing agency for Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, for 1.0 CPEU; Activity Number 134321

About the Author: Cassie I. Story, RDN, is a registered dietitian nutritionist with 13 years of experience in treating metabolic and bariatric surgery patients. She spent the first decade of her career as the lead dietitian for Drs. Blackstone, Swain, and Reynoso in Scottsdale, Arizona. For the past several years, Ms. Story has been working with industry partners in order to improve nutrition education within the field. She is currently Clinical Science Liaison for Bariatric Advantage (Aliso Viejo, California), Scientific Advisor for Apollo Endosurgery (Austin, Texas ), and Network Assistant Director of the Weight Management Dietetic Practice Group of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Disclosures: Cassie I. Story, RDN, is Clinical Science Liaison for Bariatric Advantage (Aliso Viejo, California), and Scientific Advisor for Apollo Endosurgery (Austin, Texas ).

Support for this educational activity is provided by Bariatric Advantage

Provider Contact Information: Emily A. Scullin Matrix Medical Communications, 1595 Paoli Pike, Suite 201, West Chester, PA 19380; E-mail: escullin@matrixmedcom.com

by Cassie I. Story, RDN

Bariatric Times. 2017;14(2):10–16.

Department Editor: Tracy Martinez, RN, BSN, CBN Tracy Martinez, RN, BSN, CBN, is Department Editor: Integrated Health Continuing Education, Bariatric Times; Program Director, Wittgrove Bariatric Center, La Jolla, California.

Department Editor: Tracy Martinez, RN, BSN, CBN Tracy Martinez, RN, BSN, CBN, is Department Editor: Integrated Health Continuing Education, Bariatric Times; Program Director, Wittgrove Bariatric Center, La Jolla, California.

Author: Cassie I. Story, RDN Cassie I. Story, RDN, is Clinical Science Liaison for Bariatric Advantage, Aliso Viejo, California, and Network Assistant Director of the Weight Management Dietetic Practice Group of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics.

Author: Cassie I. Story, RDN Cassie I. Story, RDN, is Clinical Science Liaison for Bariatric Advantage, Aliso Viejo, California, and Network Assistant Director of the Weight Management Dietetic Practice Group of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics.

Funding: Support for this activity was provided by Bariatric Advantage

Disclosures: Cassie I. Story, RDN, is Clinical Science Liaison for Bariatric Advantage (Aliso Viejo, California), and Scientific Advisor for Apollo Endosurgery (Austin, Texas ).

Abstract

The improved health outcomes of metabolic and bariatric surgery are undeniable, however, the high frequency of micronutrient deficiencies, especially those that are under-recognized and left untreated, can lead to irreversible consequences. Given that research shows patient adherence to micronutrient supplementation following surgery is low, it is critical that all members of the multidisciplinary care team work together to guide patients to improved adherence for improved outcomes. This article provides an overview of the literature on patient adherence and discusses barriers uncovered, including “forgetting” and “difficulty swallowing.” The author outlines the importance of patients’ adherence to a micronutrient regimen, briefly reviewing common known clinical manifestations of deficiency, such as iron deficiency anemia and bone weakening. Strategies for improving patient adherence, including clinician familiarity with available professional guidelines for micronutrient supplementation in the metabolic and baraitric surgery patient population, are also discussed.

Introduction

Metabolic and bariatric surgery is the most effective treatment strategy for severe obesity, shown to improve or resolve many comorbid conditions as well as produce sustained significant weight loss and weight maintenance.[1] Critical to the long-term health of a patient who undergoes metabolic and bariatric surgery is their adherence to numerous lifelong behaviors, including daily micronutrient supplementation.[2] Adherence rates across multiple areas of interest following metabolic and bariatric surgeries are varied. Patients exhibit greater adherence to directions from their healthcare providers prior to surgery and immediately postoperatively. The rate of adherence and follow up visits decreases as patients progress further out from surgery.[3] The improved health outcomes of metabolic and bariatric surgery are undeniable, however, the high frequency of micronutrient deficiencies, especially those that are under-recognized and left untreated, can lead to irreversible consequences.[4] Given that research shows adherence to micronutrient supplementation following surgery is low and long-term micronutrient deficiencies are high, it is critical that all members of the multidisciplinary care team work together to guide patients to improved adherence for improved outcomes.

Overview

At this time, research on adherence to micronutrient supplementation recommendations in the metabolic and bariatric surgery patient population is limited, although improving adherence recommendations seems to be important to most clinicians. Early research indicates that adherence to micronutrient supplementation is low and declines drastically in the months following surgery, while micronutrient deficiency rates increase as the patient progresses from surgery.[5]

In one of the first studies to evaluate adherence to micronutrient supplementation after metabolic and bariatric surgery,[6] approximately 90 percent of patients reported compliance with suggested supplement recommendations five months after surgery. Compliance was defined as taking one multivitamin supplement daily or every other day. By one year postoperative, self-reported micronutrient supplement intake had decreased to 50 percent.

In another study of metabolic and bariatric surgery patients,[7] mean self-reported adherence to micronutrient supplementation at 2 to 3 years postsurgery was 57.6 percent.

In a single site sub study of the Teen-Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (Teen-LABS),[8] adherence to micronutrient supplementation was investigated. Not only did this study use self-report methodology, it also utilized an electronic monitoring system that tracked the number and time of bottle openings for prescribed oral medications. The participants were instructed to take one multivitamin/multimineral supplement in the morning and one in the evening. Adherence to this recommendation was tracked prior to surgery and then again at 1 and 6 months postoperatively.

At one month postoperative, the self-reported adherence to supplement intake was 88 percent; while the electronic monitoring device data showed a 37-percent adherence rate. At six months following surgery, the self-reported adherence rate was 78 percent; while the electronic monitoring device data showed a 27-percent adherence rate. The authors concluded that the adolescents demonstrated a declining adherence over the first six months postoperatively, and that self-reported adherence was significantly greater than adherence tracked by the electronic monitoring device. Another discovery was that the subjects took zero micronutrient supplements on 66 percent of days during the study.

Nadkarni et al[9] also evaluated micronutrient supplementation adherence using electronic monitoring technology. They found an overall adherence rate of 44 percent, with rates of adherence declining as the patients progressed from surgery. The patients were instructed to take a multivitamin/multimineral supplement three times per day and were monitored for the first 50 days after surgery. During the first week adherence was 58 percent, by the last week it fell to 39 percent.

Micronutrient deficiencies following metabolic and bariatric surgery may be avoided by adherence to appropriate micronutrient supplementation and regular follow up with nutrient specific screening.[10],[11] Research shows that metabolic and bariatric surgery patients need several additional vitamin and mineral supplements, such as vitamin B12 and iron, to maintain optimal micronutrient status. Standard over-the-counter multivitamin and mineral supplements may not be adequate for preventing micronutrient deficiencies in this patient population (Table 1).[12–15]

Unlike surgical complication rates, which have been declining over the past two decades, due in part to improved surgical techniques, improved medical devices, and improved standardization of tracking complications, reports of micronutrient deficiencies are on the rise.[16] One of the most likely long-term adverse events a patient faces following metabolic and bariatric surgery is one or more micronutrient deficiencies.[17] One challenge in addressing micronutrient deficiencies in patients is a lack of consensus on the appropriate type and amount of micronutrient supplementation needed to prevent deficiencies, which has led to varying recommendations across bariatric programs nationwide.[18]

Additionally, varying levels of adherence to micronutrient supplementation make it difficult to know whether deficiencies are due to lack of adherence or increased malabsorption. Improved screening of micronutrient status would likely improve prevention and repletion recommendations and help to unify conflicting micronutrient supplementation recommendations that are given to patients.

Barriers to Adherence

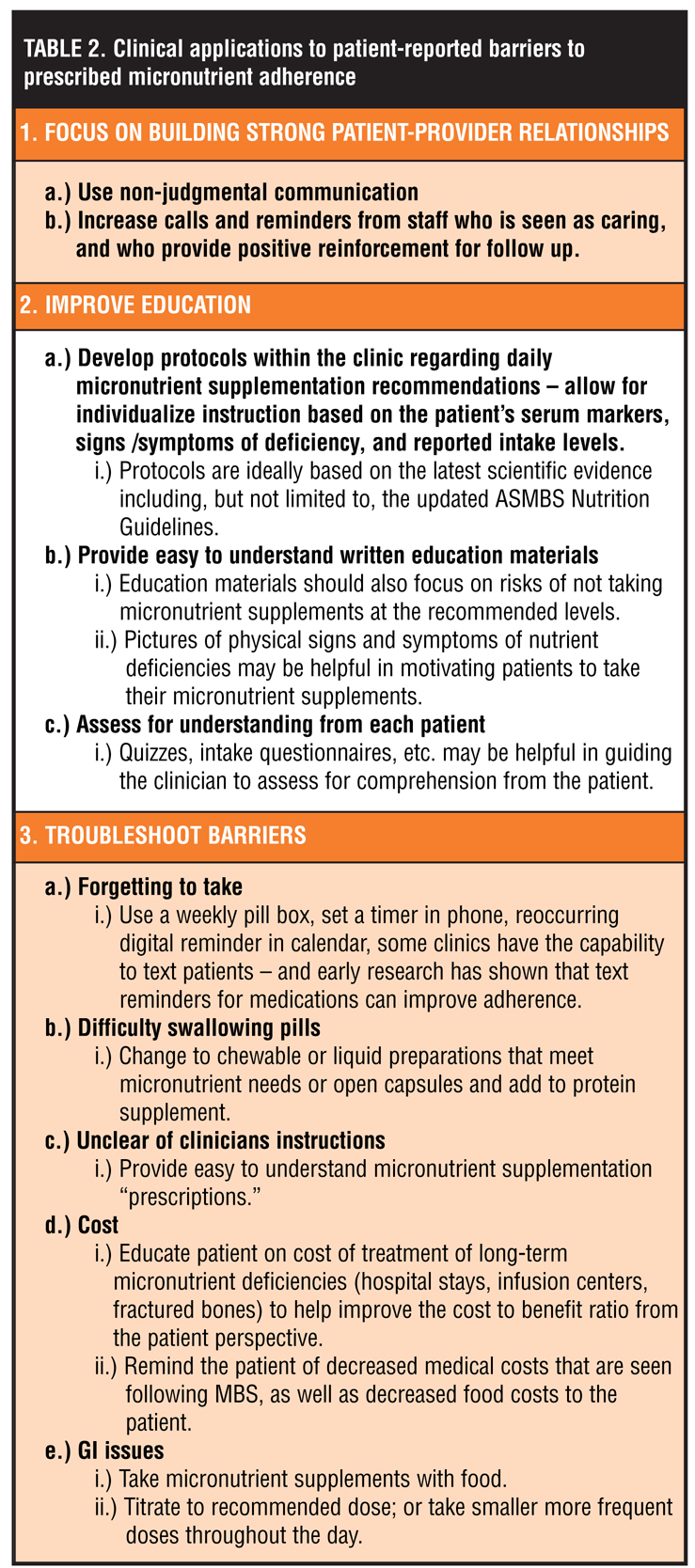

While research specific to metabolic and bariatric surgery and adherence to micronutrient supplementation recommendations is in its infancy, other studies among the general population indicate complex various barriers to adherence of oral medications and offer multi-faceted solutions to improve adherence.[19] In the Teen-LABS adherence sub study,[8] the two primary barriers identified were “forgetting” and “difficulty swallowing multivitamins.” Another barrier identified in this study was “difficult to understand doctors’ instructions.” The instructions for the majority of study participants were as follows: one tablet by mouth, twice daily. Less common, yet identified reported barriers were related to cost or gastrointestinal issues when taking micronutrient supplements. Table 2 outlines clinical applications to patient-reported barriers.

Despite education regarding the need for lifelong micronutrient supplementation following surgery, many patients likely perceive this as a general recommendation rather than a critical component of their postsurgical life. Patient perceptions regarding the potential severity of micronutrient deficiencies and benefits of prevention may have a significant effect on adherence. Nutrition deficiencies can lead to permanent and occasionally irreversible diseases or disorders.

Despite education regarding the need for lifelong micronutrient supplementation following surgery, many patients likely perceive this as a general recommendation rather than a critical component of their postsurgical life. Patient perceptions regarding the potential severity of micronutrient deficiencies and benefits of prevention may have a significant effect on adherence. Nutrition deficiencies can lead to permanent and occasionally irreversible diseases or disorders.

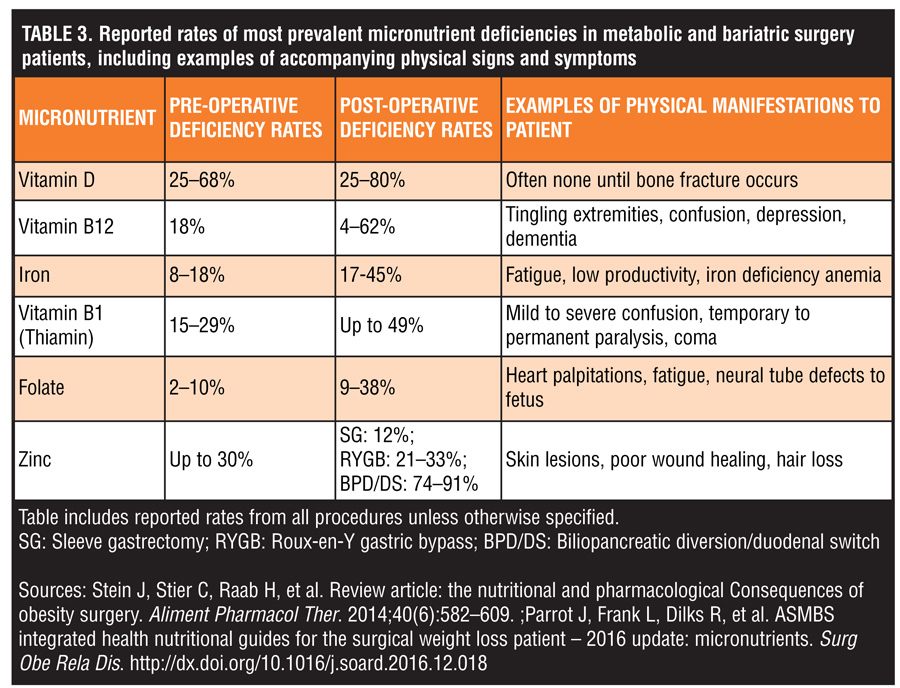

Stein et al[17] conducted a review of the nutritional and pharmacological consequences of metabolic and bariatric surgeries. The authors searched PubMed, Embase and MEDLINE using terms including, but not limited to, “bariatric surgery,” “gastric bypass,” “obesity surgery,” and “Roux-en-Y,” coupled with secondary search terms, (e.g., “anaemia,” “micronutrients,” “vitamin deficiency,” “bacterial overgrowth,” “drug absorption,” “pharmacokinetics,” and “undernutrition.”) Studies in English, French, or German published January 1980 through March 2014 were included in the study. They concluded that macro- and micronutrient deficiencies are common after metabolic and bariatric surgery. The most critical micronutrient deficiencies, depending on surgical technique, were as follows: vitamins B1, B12, and D, iron, and zinc.

The authors also reviewed the clinical manifestations of macro- and micronutrient deficiencies. Table 3 outlines reported rates of micronutrient deficiencies in metabolic and bariatric surgery patients, including examples of accompanying physical signs and symptoms.

Changing the message patients receive and ensuring they understand the potentially devastating complications that can come with micronutrient deficiencies may be an area of improvement that could help increase adherence to micronutrient supplementation.

Another consideration is that many micronutrient deficiencies lack immediate or overtly physically recognizable signs and symptoms; therefore, motivation to take micronutrient supplements is often lacking until nutrient levels become significantly altered resulting in physical manifestations. For example, anemia is a slow, progressive disorder that does not often result in physical symptoms until it has progressed to the point that it is often untreatable with oral iron preparations and infusions become necessary. Metabolic bone disease is another example of a ‘silent disease’ where the patient does not often have physical signs and symptoms until a bone fracture occurs. While we are just beginning to explore other factors that are components of bone disease postsurgery, we do know that adequate intake of many different micronutrients are critical for bone health, and that many patients—especially those who are not taking adequate micronutrient supplements—have inadequate dietary intakes of these nutrients prior to and following metabolic and bariatric surgery.[20]

Over the past nine years, several professional societies have published position statements and guidelines related to micronutrient supplementation recommendations in the metabolic and bariatric surgical patient population, yet consensus on micronutrient supplementation still varies greatly from practice to practice, and even within the practice from clinician to clinician. This lack of consensus may create confusion and uncertainty among practitioners when prescribing micronutrient supplementation for their patients.

When patients are given conflicting medication information, adherence is compromised.[21] It is imperative that patient-provider communication is enhanced and that within each practice clinicians are guiding patients with the same messaging to relieve potential confusion. Ensuring the patient understands the importance of taking life-long micronutrient supplements is equally as important as ensuring the patient understands exactly which micronutrient supplements they are required to take.

When patients are given conflicting medication information, adherence is compromised.[21] It is imperative that patient-provider communication is enhanced and that within each practice clinicians are guiding patients with the same messaging to relieve potential confusion. Ensuring the patient understands the importance of taking life-long micronutrient supplements is equally as important as ensuring the patient understands exactly which micronutrient supplements they are required to take.

Strategies for Improving Patient Adherence

Patient education by a multidisciplinary team is critical to long-term care. It is well established that education enables patients’ to have better knowledge and understanding of obesity, self-management skills, and psychosocial competencies.[22] Behavioral interventions are typically thought to be an essential component of the treatment of obesity. Focusing on patient-centered individualized education may help patients overcome barriers to lifestyle changes after surgery, including micronutrient supplementation.

Patient-centered educational approaches should ideally begin prior to surgery. Determining a patient’s readiness to change, and self-reported barriers can enable the patient to be better informed, and more prepared as they approach surgery. Wang et al[23] found that patient education by clinicians can improve patient knowledge and is linked with improved adherence. To improve adherence, education should be focused on treatment use, such as micronutrient supplementation, and expose patients to benefits and risks of adhering versus not adhering to the prescribed treatment plan.[23]

The foundation of education starts with a strong relationship between the clinician and patient. One of the most common recommendations to improve adherence is an approach that respects patient autonomy and encourages collaborative decision making. Counseling styles that are authoritative are seen as outdated and ineffective at building good rapport between the clinician and patient.

Clinicians, who listen, maintain eye contact, ask evoking questions to affirm understanding, and explain treatment plans in an understandable and unrushed manner help to build the patient-clinician relationship.[24] Clinicians should be encouraged to pay attention to their language during interviews with patients. In addition, questioning patients on micronutrient supplementation should expand beyond “Are you taking your vitamins?” Some practices have found that the use intake questionnaires at each visit provide clinician insight to assess for the patients understanding of and adherence to micronutrient supplementation. Instructing the patient to write down the type of micronutrient supplements they are taking, including brand name, dosage, time of day taken, and how often they are taking them, allows the clinician to assess for understanding of recommended doses, suggest any changes needed to the current intake, and/or address barriers if the patient is not taking the recommended dose. Written plans should also be included in patient education and at each patient encounter as research has shown that written action plans eliminate the barrier of memorization.[25]

Having a strong interdisciplinary team is also imperative in improving adherence within the metabolic and bariatric surgical patient population. Communication within the practice is essential to ensure the same message is being communicated to the patient across all disciplines.

Available Guidelines for Micronutrient Supplementation in the Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Patient Population

Being familiar with and following the established guidelines for micronutrient supplementation is a start to communicating the same recommendations throughout the practice. To date, we have several society endorsed guidelines to guide clinicians in supplement recommendations. They are as follows, listed in order of publication:

1. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS): Allied Health Nutritional Guidelines for the Surgical Weight Loss Patient.[26]

• Date: 2008

• Citation: Aills L, Blankenship J, Buffington C, et al. ASMBS Allied health nutritional guidelines for the surgical weight loss patient. Surg Obes Rela Dis. 2008;(4):S73–S108.

2. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, The Obesity Society, and American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery Medical Guidelines for Clinical Practice for the Perioperative Nutritional, Metabolic, and Nonsurgical Support of the Bariatric Surgery Patient.[27]

• Date: 2009

• Citation: Mechanick JI, Kushner RF, Sugerman HJ, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, The Obesity Society, and American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery medical guidelines for clinical practice for the perioperative nutritional, metabolic, and nonsurgical support of the bariatric surgery patient. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2009;17 Suppl 1:S1–70, v.

3. Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline: Endocrine and Nutritional Management of the Post-bariatric Surgery Patient.[28]

• Date: 2010

• Citation: Heber D, Greenway F, Kaplan L, et al. Endocrine and nutritional management of the post-bariatric surgery patient: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(11):4823–4843.

4. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE), The Obesity Society (TOS), and ASMBS: Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Perioperative Nutritional, Metabolic, and Nonsurgical Support of the Bariatric Surgery Patient—2013 Update.[29]

• Date: 2013

• Citation: Mechanick J, Youdim A, Jones D, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, Obesity Society, American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery. Clinical practice guidelines for the perioperative nutritional, metabolic, and nonsurgical support of the bariatric surgery patient – 2013 update. Endocr Pract. 2013;19(2):337–372.

5. ASMBS Integrated Health Nutritional Guidelines For The Surgical Weight Loss Patient— 2016 Update: Micronutrients.[30]

• Date: 2017

• Citation: Julie Parrott, Laura Frank, Rebecca Dilks, Lillian Craggs-Dino, Kellene A. Isom and Laura Greiman, Asmbs Integrated Health Nutritional Guidelines For The Surgical Weight Loss Patient — 2016 Update: Micronutrients. Surg Obes Relat Dis. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2016.12.018

In the latest guideline document, the authors provide specific recommended dosages for key nutrients that are critical to metabolic and bariatric surgery patients. Development of protocols within each practice is likely necessary to ensure that each member of the team is recommending the same micronutrient supplementation dosages.

These should be based on the procedure type, age, sex, and individual serum levels of the patient. Improving patient adherence to micronutrient supplementation starts at the clinic level with patient education and behavioral interventions that target barriers to taking the recommended micronutrient supplements. Recommendations for routine lab surveillance for micronutrients according to the ASMBS Nutrition Guideline 2016 update[30] include: preoperative screening for B1, B12, folate, vitamin D, calcium, iron, vitamins A, E, and K. Preoperative screening for zinc and copper is recommended for patients undergoing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) and biliopancreatic diversion/duodenal switch (BPD/DS). Within the first three months after surgery, iron should be assessed. Every 3 to 6 months after surgery and then annually screen for iron, B1, B12, folate, vitamin D. Annually screen for iron, vitamins A, D, E, K, B1, B12, folate, zinc, and copper.

Limitations/Further Areas of Study

Measurement of micronutrient supplementation adherence is hampered by the limitations of self-reporting, especially in the absence of lab values or in the presence of lab values that do not reflect the true nutrient status. For example, several nutrition studies rely on ferritin levels to assess iron status and the potential of iron deficiency anemia. However, ferritin in the absence of other biomarkers, is not an adequate test as it is an acute phase reactant and will likely be elevated in the presence of inflammation.[26] It is well known that obesity causes a chronic low-grade whole body inflammatory response.[31]

Future directions for nutritional studies should focus on standardizing biomarkers that truly reflect the micronutrient deficiency that is being screened. A database, similar to the Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program (MBSAQIP), would be helpful in tracking nutrition deficiency outcomes and help standardize micronutrient deficiency monitoring. This would assist in greater understanding of micronutrient deficiencies and proper micronutrient supplementation recommendations to prevent common deficiencies.

Additional areas of interest are in improving education on obesity and its treatments for primary care providers and building strong local relationships between metabolic and bariatric surgery practices and primary care provider practices. A good start would be to ensure that they receive education on postoperative screening of micronutrients, including what serum markers need to be evaluated and up-to-date recommendations on what micronutrient supplements metabolic and bariatric surgery patients need to take. It would also be helpful for primary care providers to know what questions to ask and the contact information local bariatric practice and/or obesity medicine specialists.

Conclusion

Self-management of any health behavior, especially one that involves complex treatment strategies, is challenging but necessary. As clinicians, we need to equip patients with proper education and individualized strategies for success. The research shows the risk for micronutrient deficiencies is greater as patients’ progress from surgery, that adherence to micronutrient supplementation decreases over time, and that follow-up clinic visits decline progressively after surgery.32 If nutrition deficiencies are not recognized as a real risk after surgery, adherence is likely to remain suboptimal. We must continue to study micronutrient status in the metabolic and bariatric surgical patient population and use scientific evidence to support our micronutrient supplementation recommendations for our patients. To help improve adherence to micronutrient supplementation we need a unified treatment message, improved education around the risks of micronutrient deficiencies, and increased behavioral strategies to guide our patients on the lifelong behaviors that are critical to their health after surgery.

Click HERE for accompanying Case Study: Treating Micronutrient Deficiency after Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass

References

- Buchwald H, Consensus Conference Panel. Consensus conference statement bariatric surgery for morbid obesity: health implications for patients, health professionals, and third-party payers. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2005;1(3):371–381.

- Hood M, Corsica J, Bradley L, et al. Managing severe obesity: understanding and improving treatment adherence in bariatric surgery. J Behav Med. 2016; 39(6): 1092–1103.

- Larjani S, Spivak I, Hao Guo M, et al. Preoperative predictors of adherence to multidisciplinary follow-up care postbariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12(2):350–356.

- Gletsu-Miller N, Wright B. Mineral malnutrition following bariatric surgery. Adv Nutr. 2013;4(5):506–517.

- Matrana M, Davis W. Vitamin deficiency after gastric bypass surgery: a review. South Med J. 2009;102(10):1025–1031.

- Cooper PL, Brearly LK, Jamieson AC, et al. Nutritional consequences of modified vertical gastroplasty in obese subjects. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999;23:382–388.

- WelchG, Wesolowski C, Zagarins S. Evaluation of clinical outcomes for gastric bypass surgery: Results from a comprehensive follow-up study. Obes Surg. 2011;21(1):18–28.

- Avani C, Modi M, Zeller S. et al. Adherence to vitamin supplementation following adolescent bariatric surgery. Obesity. 2013;21:190–195.

- Nadkarni A, Domeisen N, Hill D, et al. Patient adherence to vitamin therapy following bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Rel Dis. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2016.08.346 Accessed 2/3/17.

- Pournaras D, le Roux C. After bariatric surgery, what vitamins should be measured and what supplements should be given? Clin Endocrinol. 2009;71(3):322–325.

- Saltzman E, Karl JP. Nutrient deficiencies after gastric bypass surgery. Annu Rev Nutr.2013:33:183–203.

- Shankar P, Boylan M, Sriram K. Micronutrient deficiencies after bariatric surgery. Nutrition. 2010;26(11-12):1031–1037.

- Xanthakos, S. Nutritional deficiencies in obesity and after bariatric surgery. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2009;56(5):1105–1121.

- Gasteyger C, Suter M, Gaillard R, et al. Nutritional deficiencies after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity often cannot be prevented by standard multivitamin supplementation. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87(5):1129–1133.

- Centrum Chewables product labeling. http://labeling.pfizer.com/ShowLabeling.aspx?id=2559 Accessed 2/3/17.

- Gudzune K, Huizinga M, Chang H, et al. Screening and diagnosis of micronutrient deficiencies before and after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2013;23(10):1581–1589.

- Stein J, Stier C, Raab H, et al. Review article: the nutritional and pharmacological Consequences of obesity surgery. Al Pharm Ther. 2014;40:582–609.

- Brolin R, Leung M. Survey of vitamin and mineral supplementation after gastric bypass and biliopancreatic diversion for morbid obesity. Obes Surg. 1999;9:150–154.

- Brown M, Bussell J. Medication adherence: WHO cares? Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86(4):304–314.

- Pizzorno L. Bariatric surgery: bad to the bone, part 1. Integr Med. 2016;15(1):48–54.

- Elstad E, Carpenter D, Devellis R, et al. Patient decision making in the face of conflicting medication information. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 2012 Aug 28;7:1–11.

- Ziegler O, Sirveaux MA, Brunaud L, Reibel N, Quilliot D. Medical follow up after bariatric surgery: nutritional and drug issues general recommendations for the prevention and treatment of nutritional deficiencies. Diabetes Metab. 2009;35(6 Pt 2):544–557.

- Wang W, He G, Wang M, Liu L, Tang H. Effects of patient education and progressive muscle relaxation alone or combined on adherence to continuous positive airway pressure treatment in obstructive sleep apnea patients. Sleep Breath. 2012;16(4):1049–57.

- Vermeire E, Hearnshaw H, Van Royen P, et al. Patient adherence to treatment: three decades of research. A comprehensive review. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2001;26:331–342.

- Feldman SR. Practical Ways to Improve Patients’ Treatment Outcomes. Winston-Salem, North Carolina: Medical Quality Enhancement Corporation, 2008.

- Aills L, Blankenship J, Buffington C, et al. ASMBS Allied health nutritional guidelines for the surgical weight loss patient. Surg Obes Rela Dis. 2008;(4):S73–S108

- Mechanick JI, Kushner RF, Sugerman HJ, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, The Obesity Society, and American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery medical guidelines for clinical practice for the perioperative nutritional, metabolic, and nonsurgical support of the bariatric surgery patient. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2009;17 Suppl 1:S1–70

- Heber D, Greenway F, Kaplan L, et al. Endocrine and nutritional management of the post-bariatric surgery patient: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(11):4823–4843.

- Mechanick J, Youdim A, Jones D, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, Obesity Society, American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery. Clinical practice guidelines for the perioperative nutritional, metabolic, and nonsurgical support of the bariatric surgery patient – 2013 update. Endocr Pract. 2013;19(2):337–372.

- Parrot J, Frank L, Dilks R, et al. ASMBS integrated health nutritional guides for the surgical weight loss patient – 2016 update: micronutrients. Surg Obe Rela Dis. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2016.12.018 . Accessed 1/31/17.

- Esser N, Legrand-Poels S, Piette J, et al. Inflammation as a link between obesity, metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;105(2):141–150.

- Bradley L, Sarwer D, Forman E. A survey of bariatric surgery patients’ interests in post-operative interventions. Obes Surg. 2016;26(2):332–338.

- Bays H, Kothari S, Azagury D, et al. ASMBS Guidelines/Statements, Part 2: Lipids and bariatric procedures Part 2 of 2: scientific statement from the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS), the National Lipid Association (NLA), and Obesity Medicine Association (OMA). Surg Obes Rel Dis. 2016;12:468-495.

Category: Past Articles, Review