Chylous Ascites Associated With Internal Hernia After Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass For Morbid Obesity: A Case Report

FIGURE 1. Abdominal CT performed on 3/3/2018 revealing typical “swirl sign” indicatinginternal hernia

By Ann M. Defnet, MD; Marina Kurian, MD, and Andrea Bedrosian, MD

Funding: No funding was provided for this article.

Disclosures: The author reports no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this manuscript.

Author Affiliation: Drs. Defnet, Kurian, and Bedrosian are from New York University Langone Health, Department of Surgery, New York, New York.

Bariatric Times. 2018;15(8):14–15.

Abstract: We present a case of internal hernia after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) for morbid obesity associated with the presence of chylous ascites. Internal hernia is one of the most common complications after laparoscopic RYGB, and its incidence has been found to be decreased with antecolic/antegastric Roux limb positioning and closure of all mesenteric defects. Chylous ascites is a rare finding during exploration for internal hernia or small bowel strangulation from any cause, but it is thought to be secondary to chronic obstruction of the low flow lymphatic channels with subsequent leakage of chyle into the peritoneum without obstruction of high flow venous and arterial vessels.

Keywords: laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), internal hernia, chylous ascites

Introduction

lnternal hernia (IH) is one of the most common complications following laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) for treatment of morbid obesity, with an incidence from 1 to 14 percent.[1–5] IH occurs when the bowel herniates through mesenteric defects created during mobilization of the Roux limb to the gastric pouch.[6] Clinically, patients can present with intermittent abdominal pain or obstructive symptoms, or present acutely with small bowel obstruction or strangulation. Diagnosis is made with high clinical suspicion, augmented by abdominal computed tomography (CT). Although not present in all IH, the typical “swirl sign” has high sensitivity for IH.[7] Emergent surgical intervention is the standard treatment for IH to reduce the hernia, repair the defect, and assess for ischemic bowel. Diagnostic laparoscopy is also advocated in patients with high clinical suspicion without typical findings on abdominal CT.[8]

We present a case of internal hernia after laparoscopic RYGB associated with chylous ascites.

Case Report

A 39-year-old female patient with a body mass index (BMI) of 40.7kg/m2 and Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) underwent RYGB on January 17, 2017. The gastrojejunostomy was created in an antecolic/antegastric fashion with a 100cm Roux limb and 150cm biliopancreatic limb. Of note, Petersen’s defect was closed with a 2-0 prolene purse string suture approximating the base of the mesocolon to the Roux limb mesentery back to the mesocolon up to the the appendicies epiploicae of the transverse colon. The additional jejunal mesenteric defect was also closed with a running 2-0 prolene suture. The patient tolerated the procedure well without adverse event and was discharged tolerating a liquid diet on postoperative Day (POD) 2. On outpatient follow-up, she had no issues, her diet had advanced appropriately, and she achieved adequate weight loss.

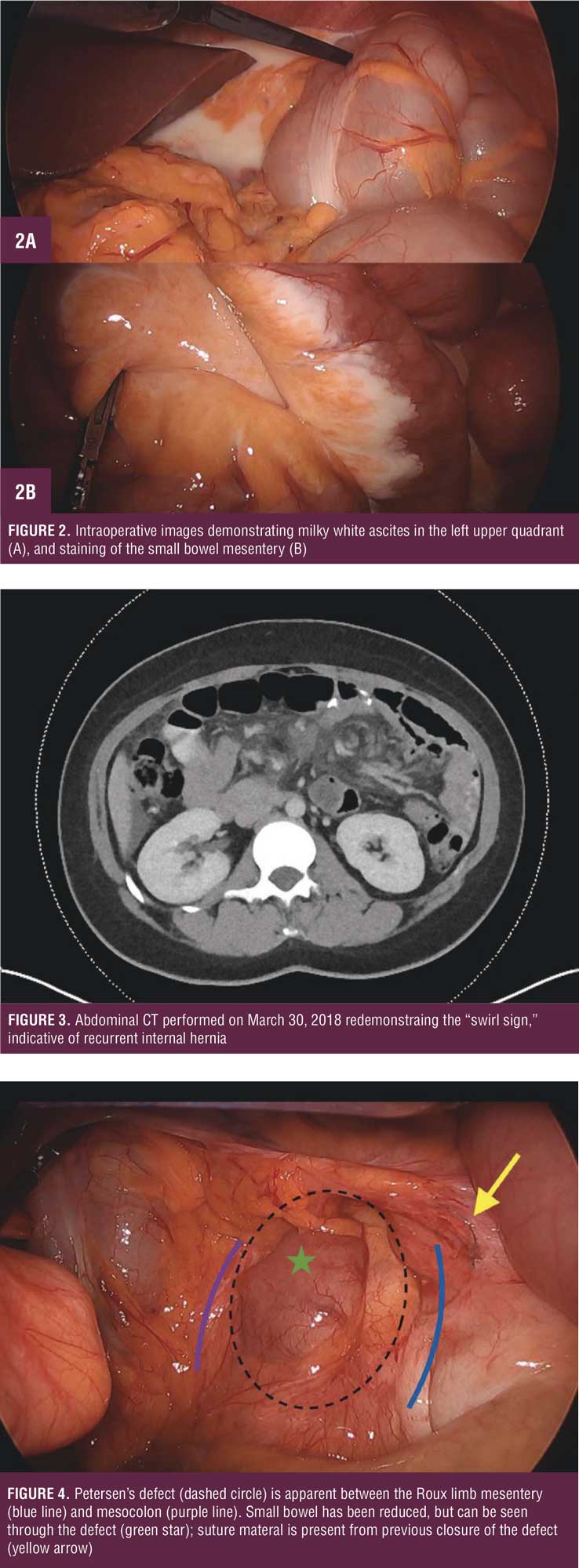

She presented to the emergency department on March 3, 2018, her BMI now 26kg/m2 (77% excess body weight [EBW]), with severe left upper quadrant pain for one day associated with nausea and vomiting. Vital signs and laboratory work were within normal limits, including a venous lactate level of 0. 86mmol/L. CT abdomen/pelvis revealed a swirl sign concerning for IH, with possible impingement of the superior mesenteric vein (SMV), mesenteric stranding, and free pelvic fluid (Figure 1). She was taken to the operating room, where diagnostic laparoscopy revealed viable small bowel with moderate amount of milky white appearing ascites without succus (Figure 2a). Portions of the small bowel mesentery were also stained white (Figure 2b). A single adhesion was present from the omentum to the anterior abdominal wall over the cecum, causing partial obstruction of the jejunojeunostomy. After lysis of this adhesion, the bowel was run from ligament of Treitz to the terminal ileum. Petersen’s defect appeared adequately closed. The ascitic fluid had a triglyceride level of 3770mg/dL, confirming chylous ascities. The patient recovered uneventfully and was discharged POD 2 tolerating a regular diet.

She presented to the emergency department on March 30, 2018, with similar left upper quadrant abdominal pain associated with nausea for one day. Her vital signs and laboratory work were within normal limits. CT abdomen/pelvis (Figure 3) showed similar findings of IH with slightly increased mesenteric stranding and free fluid. She was taken to the operating room for diagnostic laparoscopy, where a moderate amount of chylous ascites was again present. All bowel was viable, but during this exploration, the entire biliopancreatic limb, common channel, and distal anastomosis was found to be herniated through the base of Petersen’s defect (Figure 4). Suture material was present surrounding Petersen’s defect (Figure 4) . The bowel was successfully reduced, and Petersen’s defect was closed from its base to the gastric pouch with 2-0 Ethibond Excel suture (Ethicon, Cincinnati, Ohio). A small opening in the additional mesenteric defect was also closed with 2-0 Ethibond Excel suture. She recovered uneventfully and was discharged POD 2 tolerating a regular diet.

Discussion

This case demonstrates a typical diagnosis and presentation of IH after RYGB with an atypical finding of associated chylous ascites. The incidence of IH varies based on method of Roux limb formation during RYGB, as well as whether the mesenteric defects are closed. A recent meta-analysis reported that the antecolic/antegastric position of the Roux limb has a decreased rate of IH versus the retrocolic/retrogastric position at 1.3 versus 2.3 percent.[9] Multiple studies have reported that closure of the mesenteric defects also decreases the incidence of IH and recommend closure of all mesenteric defects.[10–12] In 2016, Chowbey found a reduction in IH from 3.6 to 1.7 percent after instituting closure of all mesenteric defects at their center.[11] In a meta-analysis by Geubbles, antecolic RYGB with closure of both Petersen’s defect and the additional jejunal mesenteric defect was shown to have the lowest rate of IH at one percent. An antecolic Roux limb with all defects left open and retrocolic Roux limb with closure of both mesenteric and mesocolonic defects were both found to have a twopercent incidence of IH. The highest incidence of IH was found in antecolic Roux limbs with closure of the jejunal defect only, and in retrocolic Roux limbs with closure of all defects at three percent.[6] Other factors have also been found to correlate with an increased incidence of IH, including rapid weight loss.[6,13] Despite having performed an antecolic/antegastric RYGB with closure of both Petersen’s defect and the jejunal mesenteric defect, our patient developed IH through Petersen’s defect, likely secondary to rapid weight loss.

Chylous ascites is an abnormal finding during surgical exploration for IH, small bowel volvulus, or closed loop obstruction. Only a few previous cases have been reported in the literature[14,15] and only one after RYGB for morbid obesity.[16] Chylous ascites, a milky white fluid without odor, is most commonly seen in obstruction of the lymphatic channels from abdominal malignancy or cirrhosis. Diagnosis is confirmed by determining an elevated triglyceride level of the ascitic fluid (>110mg/dL). The mechanism of chyloperitoneum in strangulated bowel is proposed to be from chronic obstruction of the low flow lymphatic channels without complete obstruction of the higher flow venous or arterial vessels.[14] Over time, chyle builds up within the small bowel mesentery from this obstruction and eventually leaks into the peritoneal space, causing chylous ascites. Interestingly, no bowel has been reported to be frankly ischemic in any reports of chyloperitoneum secondary to intestinal obstruction, and the chylous ascites is reported to quickly resolve after correction of the obstruction.[14]

Conclusion

In conclusion, our case illustrates the rare finding of chylous ascites secondary to chronic obstruction from IH after RYGB.

References

- Rodriguez A, Mosti M, Sierra M, et al. Small bowel obstruction after antecolic and antegastric laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: could the incidence be reduced? Obes Surg. 2010;20:1380–1384.

- Rausa E, Bonavina L, Asti E, et al. Rate of death and complications in laparoscopic and open Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: A meta-analysis and meta-regression analysis on 69,494 patients. Obes Surg. 2016;26:1956–1963.

- Kristensen SD, Jess P, Floyd AK, et al. Internal herniation after laparoscopic antecolic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a nationwide Danish study based on the Danish National Patient Register. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12:297–303.

- Elms L, Moon RC, Varnadore S, et al. Causes of small bowel obstruction after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a review of 2,395 cases at a single institution. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:1624–1628.

- Champion JK, Williams M. Small bowel obstruction and internal hernias after laparoscopic Rouxen-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2003;13:596–600.

- Geubbels N, Lijftogt N, Fiocco M, et al. Meta-analysis of internal herniation after gastric bypass surgery. Br J Surg. 2015;102:451–460.

- Dilauro M, McInnes MD, Schieda N, et al. Internal hernia after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: optimal CT signs for diagnosis and clinical decision making. Radiology. 2017;282:752–760.

- Facchiano E, Leuratti L, Veltri M, et al. Laparoscopic management of internal hernia after Rouxen- Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2016;26:1363–1365.

- Al Harakeh AB, Kallies KJ, Borgert AJ, Kothari SN. Bowel obstruction rates in antecolic/antegastric versus retrocolic/retrogastric Roux limb gastric bypass: a meta-analysis. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016; 2:194–198.

- Al-Mansour MR, Mundy R, Canoy JM, et al. Internal hernia after laparoscopic antecolic Rouxen- Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2015;25:2106–2111.

- Chowbey P, Baijal M, Kantharia NS, et al. Mesenteric defect closure decreases the incidence of internal hernias following laparoscopic Rouxen- Y gastric bypass: a retrospective cohort study. Obes Surg. 2016;26:2029–2034.

- Obeid A, McNeal S, Breland M, et al. Internal hernia after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18:250–255; discussion 255–256.

- Gandhi AD, Patel RA, Brolin RE. Elective laparoscopy for herald symptoms of mesenteric/internal hernia after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2009;5:144–149; discussion 149.

- Harino Y, Kamo H, Yoshioka Y, et al. Case report of chylous ascites with strangulated ileus and review of the literature. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2015;8:186–192.

- Akama Y, Shimizu T, Fujita I, et al. Chylous ascites associated with intestinal obstruction from volvulus due to Petersen’s hernia: report of a case. Surg Case Rep. 2016;2:77.

- Hidalgo JE, Ramirez A, Patel S, et al. Chyloperitoneum after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB). Obes Surg. 2010; 20:257–260.

Category: Case Report, Past Articles