Fasting versus Carb-Loading: What’s the Evidence for Your Enhanced Recovery after Bariatric Surgery Program?

by Liz Goldenberg, MPH, RD, CDN

by Liz Goldenberg, MPH, RD, CDN

Ms. Goldenberg is with New-York Presbyterian Hospital, Weill Cornell College of Medicine of Cornell University, Department of Surgery, New York, New York

Funding: No funding was provided for this article.

Disclosures: The author reports no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this manuscript.

Bariatric Times. 2018;15(11):28–29.

This column is dedicated to providing evidence-based bites of information for the clinician on nutritional considerations in the bariatric patient.

Abstract: Bariatric surgery enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) programs are gaining in popularity as other surgical specialties are demonstrating improved patient outcomes. One key component to most ERAS protocols involves instructing patients to ingest carbohydrate drinks immediately prior to surgery. This relatively new advisement contends with decades of belief in the doctrine of preoperative fasting.

In this article, the author reviews the tradition of preoperative fasting and recent research that supports moving away from this practice. Instead, programs are increasingly recommending an opposite approach—”carbohydrate-loading.”

Keywords: Overweight, obesity, bariatric surgery, nutrition, preoperative nutrition, fasting, carbohydrates, carb-loading, enhanced recovery

Background

Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) is a protocol-guided, multimodal, multidisciplinary evidence-based interventional perioperative approach to major surgery. Colorectal, vascular, and thoracic surgery have led the way in providing evidence to support the benefits of employing ERAS protocols. Carbohydrate loading (carb-loading) is believed to be a key component to these programs. While the main goals of ERAS protocols are to reduce length of stay and complications, cost reduction and increased patient satisfaction have also been realized with such programs. While bariatric surgery ERAS programs are in their early stages and lack standardization, new research is beginning to demonstrate positive outcomes relating to patient turnover, operating room times, costs, and length of hospital stay when modifications are employed at all phases of surgery—preoperatively, intraoperatively, and postoperatively.1,2

The Tradition of Preoperative Fasting

Among the pertinent preoperative ERAS components is the move to eliminate the heretofore doctrine of fasting the patient. Six to eight hours of preoperative fasting is still considered fundamental by many anesthesiologists and surgeons. The rationale for this prescription is to reduce gastric acidity and volume with a consequent decrease in the risk of vomiting and gastric content aspiration.3 However, this constraint was instituted when anesthetic techniques were immature.4 Modern guidelines take into account that there is no evidence that a shortened fast of 2 to 3 hours, which includes oral fluids, increases the risk of aspiration, regurgitation or related morbidity as compared with nothing by mouth (NPO) after midnight.5,6

The recommendation for more flexible fasting times is also bolstered by the understanding that fasting leads to insulin resistance. Furthermore, the acute-phase response and loss of lean body mass only increase in the setting of prolonged fasting. In an insulin resistant state, cell glucose uptake is reduced and glycogen formation halts such that liver and muscle glycogen are depleted. Hyperglycemia results from enhanced endogenous glucose production. Maintaining close glucose control is paramount to decreasing the risk of surgical complications and mortality.6

The effects of this starvation scenario are further amplified by the fact that many patients in actuality are deprived of nutrition for 12 hours or more due to the impact of scheduling issues and operating room delays.4 Another consideration is that patients, not surprisingly, seem to be happier when they are not fasted. Patients are less thirsty, hungry and anxious.3

Beyond the effects of a fasting state, surgery itself imparts significant stress on the patient. The body unleashes a systemic reaction to the surgical insult, incorporating hematologic, endocrine, immunologic, and sympathetic nervous system responses. Hypermetabolism and hypercatabolism occur, which in turn may lead to muscle wasting, impaired immune function and wound healing, and even organ failure and death. Cortisol, catecholamines, cytokines, and glucagons are among the inflammatory markers that diminish insulin action, which furthers the risk for hyperglycemia in the fasting patient.7

The Role of Nutrition and Carbohydrate Loading

Poor nutritional status has long been associated with suboptimal surgical outcomes.3 Both the existence of malnutrition preoperatively, and the common practice of withholding nutrition just prior to surgery, increase postoperative complications and length of stay.8 Reduced immunocompetence, impaired wound healing, loss of muscle tissue/strength, and increased readmissions are among the concerns that arise from operating on malnourished individuals. In short, well-nourished patients experience better outcomes.3 Finally, it is important to acknowledge that surgery of the upper gastrointestinal tract, versus, for example, vascular surgery, imparts unique nutritional risks due to its corresponding impact on oral intake.

Carb-loading of the preoperative patient resembles that of the marathoner, the goal being to maximize glycogen stores to support gluconeogenic substrates through surgery, rather than drawing on lean body tissue. Providing a carbohydrate drink reduces insulin resistance and tissue glycosylation through surgery, helps postoperative glucose control, and enhances return of bowel function.

The amount of carbohydrate required to induce an effect must be enough to shift the body from a fasted to a fed state. Oral ingestion of 50g of carbohydrate has been shown to produce a release of insulin similar to that seen after ingestion of a mixed meal. It has been proposed that 100g of carbohydrate be consumed the night before surgery and another 50g close to two hours before surgery.3

The 2012 North American Surgical Nutrition Summit provides summary points and consensus recommendations which outline 800mL of a 12.5-percent carb drink be consumed the night before surgery and 400mL the next morning two hours prior to induction of anesthesia for surgery, unless contraindicated.8 This equates to 100g and 50g of carbohydrates respectively. It is important to note that the consensus recommendation summary does not provide examples of contraindications and one potential contraindication could be the presence of diabetes.

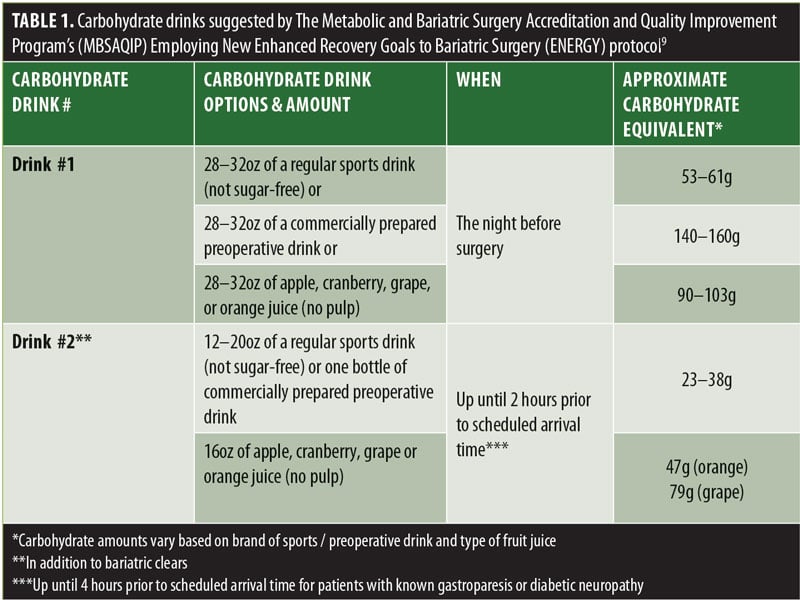

The Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program’s (MBSAQIP) Employing New Enhanced Recovery Goals to Bariatric Surgery (ENERGY)9 protocol suggests carbohydrate drinks as per Table 1.

Vanderbilt University recently published the details of their bariatric surgery ERAS program. The carb-loading component of the program outlines the consumption of 12oz of Gatorade G2® drink (equivalent to 7 of carbs, significantly less than the above examples) before bed and another 12oz of G2® three hours preoperatively. Their findings included significant reductions in perioperative opioid use, as well as decreases in postoperative nausea and early emergency room visits.10

Diabetes and Carb-loading

There are hypothetical risks to carb-loading in individuals with diabetes. Among the considerations are aspiration pneumonia due to delayed gastric emptying and worsening of hyperglycemia. Concerning delayed gastric emptying, chronically elevated glucose can lead to nervous system dysfunction. Affected individuals have deranged proximal gastric accommodation and contraction after solid meals and reduced frequency of antral contractions. Aside from the aforementioned concerns for the impact of hyperglycemia on complication risk, acutely elevated glucose levels can themselves delay gastric emptying; the rise in glucose decreases stomach and small bowel contractility and stimulates localized pyloric contraction. Two studies support the safety of carb-loading in diabetics. One study used a 15g carb drink in subjects with variable diabetes control (n= 86, median HbA1c 9.3%), a second used a 50g carb drink in a better-controlled group (n= 25, mean HbA1c 5.6 and 6.8% in noninsulin- and insulin-treated subjects, respectively). Both studies found complete gastric emptying at 180 minutes or less, thus a 2-to-3 hour time frame for consumption of a liquid load should not be problematic. Furthermore, gastric content needs to be 200mL for regurgitation and pulmonary aspiration to occur. 11

A second potential contraindication may arise from the fact that we are discussing a population with morbid obesity. However, it has been shown that patients with morbid obesity have the same gastric emptying characteristics as lean patients.12

Beyond Carbohydrates

Does giving other nutrients preoperatively enhance recovery or improve outcomes in bariatric surgery patients? Attention has been paid to supplying supplemental protein and immune-enhancing substances, such as n-3 fatty acids, arginine, glutamine, and nucleotides prior to surgery. “Immunonutrition” has the potential to reduce inflammatory markers, enhance the immune response, improve wound healing, reduce postoperative complications and hasten recovery. Thus far, studies which provide immune-enhancing substances preoperatively (and perioperatively) in surgical patients have shown mixed results.3 Nevertheless, The North American Surgical Nutrition Summit summary points include consideration be given to providing immunonutrition and carb-loading together with other aspects of the ERAS program.8 Research exists which specifically involves provision of immunonutrition as part of a bariatric surgery ERAS. There is likewise a scarcity of data pertaining to the role of preoperative protein supplementation in bariatric surgery patients. One study of RYGB patients compares patients who consumed preoperative carb drinks and got early postoperative protein-containing peripheral parenteral nutrition (PPN) to those who were kept NPO after midnight. Participants who consumed a 100g carb drink 12 hours before and a 50g carb drink two hours before surgery also received 50g of protein via PPN. Authors reported no significant decrease in complications or length of stay and, at one year after surgery, no difference in lean body mass or excess weight loss between the two groups.13

Summary

As more data are published on the use of ERAS in bariatric surgery, the role of a carb-loading component should become more defined. While there are as yet no definitive recommendations for the carbohydrate source or amount, the data seem to support a move away from preoperative fasting.

References

- Alvarez A, Goudra BG, Singh PM. Enhanced recovery after bariatric surgery. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2017; 30(1):133–139.

- Malczak P, Magdalena P, Major P, et al. Enhanced Recovery after Bariatric Surgery: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Obes Surg. 2017 27:226–235.

- Kratzing. Preoperative nutrition and carbohydrate loading. Proc Nutr Soc. 2011;70(3):311–315

- Pimenta GP, de Aguilar-Nascimento JE. Prolonged preoperative fasting in elective surgical patients: why should we reduce it? Nutr Clin Pract. 2014;29(1):22–28.

- Brady M, Kinn S, Stuart P. Preoperative fasting for adults to prevent perioperative complications (review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Issue 5. 2003;(4):CD004423.

- Sarin. Enhanced recovery after surgery-Preoperative fasting and glucose loading-A review. J Surg Oncol. 2017;116(5):578–582. Epub 2017 Aug 28.

- Finnerty CC, Mabvuure NT, Ali A, Kozar RA, Herndon DN. The surgically induced stress response. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2013 Sep;37(5 Suppl):21S-9S.

- McClave SA, Kozar R, Martindale RG, et al. Summary points and consensus recommendations from the North American Surgical Nutrition Summit. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2013;37(5 Suppl):99S–105S.

- Brethhauer S. ENERGY Protocol and Deal Breakers. MBSAQIP 2017.

- King AB, Spann MD, Jablonski P, et al. An enhanced recovery program for bariatric surgical patients significantly reduces perioperative opioid consumption and postoperative nausea. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018 Feb 13.

- Albalawi Z, Laffin M, Gramlich L, Senior P, McAlister FA. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) in Individuals with Diabetes: A Systematic Review. World J Surg. 2017;41(8):1927-1934.

- Lassen K, Soop M, Nygren J, et al. Consensus review of optimal perioperative care in colorectal surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Group recommendations. Arch Surg. 2009;144(10):961–969.

- Azagury DE, Ris F, Pichard C, Volonté F, Karsegard L, Huber O. Does perioperative nutrition and oral carbohydrate load sustainably preserve muscle mass after bariatric surgery? A randomized control trial. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2015;11(4):920–6.

Category: Nutritional Considerations in the Bariatric Patient, Past Articles