Raising the Standard: Promoting the Culture of Patient and Staff Safety in Bariatric Surgery

by Charmaine V. Gentles, DNP, ANP-BC, RNFA, and Dominick Gadaleta, MD, FACS, FASMBS

by Charmaine V. Gentles, DNP, ANP-BC, RNFA, and Dominick Gadaleta, MD, FACS, FASMBS

Ms. Gentles is the Program Manager, Bariatric Surgery North Shore University Hospital, Northwell Health and RNFA Program Coordinator & Supervising Clinical Faculty, Hofstra Northwell School of Graduate Nursing & Physician Assistant Studies in Hempstead, New York. Dr. Gadaleta is Chair of the Department of Surgery at Southside Hospital and Director of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery at North Shore University Hospital, Northwell Health in Manhasset, New York; and Associate Professor of Surgery at Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell in Hempstead, New York.

Funding: No funding was provided for this article.

Disclosures: The authors reports no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Bariatric Times. 2019;16(11):19–20.

Patient safety is crucial for excellence in healthcare delivery.1 Safety, as defined by the Institute of Medicine (IOM), is “the prevention of harm to patients.”1,2 Within the context of this definition, emphasis is placed on healthcare organizations that have systems in place to avoid errors, one that provides opportunities where individuals can learn when errors do occur and one that builds an environment where the culture of safety is the foundation for patients, providers, and the community it serves.2 The IOM report states that healthcare delivery systems must function at a higher level to avoid errors and that delivery of care must be consistent.2

Various regulatory agencies and healthcare institutions have developed a number of patient safety initiatives to ameliorate adverse events in many surgical specialties; however, the number of adverse events remains excessively high.3,4 Nongeneric strategies, such as surgical checklist and safety guidelines, are just not enough and do not target specific surgical subspecialties that would improve the care of surgical patients. Healthcare agencies, such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), developed generic guidelines surrounding patient safety systems, standards, and processes dedicated to improve the care of surgical patients and to reduce surgical errors.5 Accrediting bodies, such as the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) and American College of Surgeons (ACS), has established specific subspecialty standards to improve care outcomes. In this article, we provide specific patient safety approaches that influenced bariatric patient and staff safety at North Shore Hospital.

Patient Safety Strategies

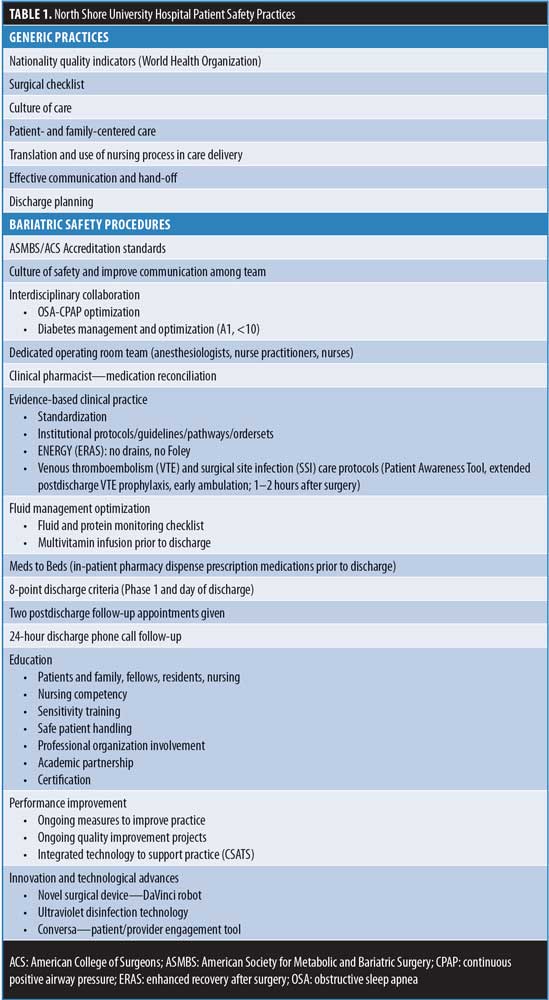

When caring for bariatric patients, special equipment and actions are needed regarding safe patient handling to prevent injury. At North Shore University Hospital, the bariatric program places emphasis on exceptional patient care and safe patient practices that are promoted through the use of empirical evidence grounded in the principles of leadership, teamwork, and behavior. The patient safety practices used are interventions that primarily focus on reducing risks associated with care outcomes. Improvement strategies include having the appropriate resources, as well as providing education that is clear and consistent. The center provides annual mandatory education on postoperative complications and ergonomics training. Ergonomics training involves the appropriate use of transfer devices, including the mobile air transfer system (MATS), which allow for safer transfer and positioning of bariatric patients from the operating room (OR) table to bariatric bed and throughout the entire hospital. This device allows for transfer with less exertion when moving and lifting the bariatric patients. The center’s program safety practices are included in the organization policy and procedure manual. Outlined in Table 1 are logical patient safety strategies, both generic and specific, that are included in the program’s manual.

Role of Leadership in Patient & Staff Safety

Our organizational senior executive leaders play key roles in leading and promoting safe care. Patient-centered care and culture of care is the organization’s framework for nursing practice. They assume leadership by establishing a culture of safety, embracing improvement strategies, monitoring progress and performance, and ensuring the organization meets the needs of the patients and communities they serve. Most recently, Northwell’s leadership announced its investment in an ultraviolet (UV) disinfection technology that reduces the risk of hospital-acquired infections. This technology uses UV light to surround surgical equipment exposing all surface areas at high intensity in 90-second stretches. This device, based on an American Journal of Infection Control study,6 eliminates pathogens up to 97.7 percent. In addition, this technology will optimize environmental cleanliness that could potentially cause infection. The metabolic and bariatric surgeons also promote patient safety by providing a clear vision to the interdisciplinary team on what is expected of their involvement in the care of bariatric patients. Concerns are addressed and strategies are implemented to minimize the majority of the challenges routinely encountered in practice. Nursing leadership also shows their dedication to bariatric patients by maintaining annual assessment of nurses’ competency in the designated areas of care to ensure delivery of exceptional care.

Role of Clinical Providers in Patient Safety Practices

Similar to any other healthcare facility, challenges are encountered when implementing patient safety principles specific to the bariatric patients. Patient safety is at the forefront of the center’s bariatric care delivery model, and the dedicated bariatric nurse practitioner (NP) is seated in this position to ensure that everyone (nurses, residents, physician assistants [PAs]) works together as a team to maintain patient safety practices in real time. The center’s bariatric program channels the delivery of care to bariatric patients through the IOM’s six domains for quality improvement (i.e., “safe, effective, timely, efficient, patient-centered, and equitable”).2,7 In healthcare, clinicians are constantly reminded of the patient’s expectations before and after surgery. The care team is provided with educational opportunities (e.g., annual in-service, advanced education) at local and national bariatric meetings to assure appropriate care is delivered to the bariatric patients. Residents and fellows receive ongoing bariatric education during morbidity and mortality meetings, at grand rounds, and from daily interactions with the bariatric surgery team.

Gaps in communication often exist between healthcare providers and patients regarding surgical care or medication management, which could present harm to the patient.3 In the preoperative phase, potential errors are minimized by obtaining informed consent, which allows the patient to recall and restate what information was given by the physician to verify their understanding of the planned procedure. In efforts to minimize medication errors, implementing an effective system is important, such as making sure the clinical pharmacist in the program successfully reconciles a patient’s medication immediately prior to surgery and before discharge.

Engaging patients in their care supports safe practice.5,8 Higher body mass index (BMI) is considered a predictive risk factor for difficult endotracheal intubation. One of the center’s safe practices is ensuring an anesthesiologist and a second experienced anesthesia colleague is present at induction for patients with BMI greater than 40kg/m2 to facilitate safe and successful airway management.

Effectiveness is demonstrated through process-of-care measures, such as the administration of low molecular weight unfractionated heparin (LMWUH) preoperatively and throughout the hospital course. This strategy, which aims for a desirable outcome of prevention of thromboembolism and administering LMWUH at the prescribed time, determines whether the healthcare provider performed the processes in a timely manner or avoided the processes, thus putting the patient at risk for harm. The center uses a dedicated team in the operating room and designated bariatric unit in the postoperative area to optimize efficiency. On the scheduled days for surgery, the anesthesiologist, surgeon, fellow, residents, NP, scrub tech, and nurse work together for the full OR day. Having a dedicated team and unit provides for a stable and consistent environment, which improves performance.7

We ensure that nurses demonstrate their ongoing level of commitment to the safety of bariatric patients by participating in morning huddles, weekly patient safety rounds, and hourly in room–rounding (patient-centered care). They assessed patient needs, check dietary preferences, and do clinical assessments. Best practices are shared with the nurses to provide consistent care in all phases of care. The nurses are particularly attentive to bariatric order sets and protocols (e.g., enhanced recovery after surgery [ERAS], discharge criterion) to ensure a safe and positive patient experience. Frequently, increased hospital admissions and unplanned emergency surgical procedures often increase bed demands in the postanesthesia care unit (PACU) and on the postsurgical care unit, which alters the discharge process. Therefore, to improve throughput and prevent overcrowding of the PACU, and bariatric floor, in 2012 and 2017 we developed and implemented two sets of eight-point bariatric criterion (Phase 1 & Day of Discharge). The nursing team use these tools as a guide for a safe, efficient, and timely discharge that ultimately supports quality care, improves patient satisfaction, and shortens length of stay, thus decreasing hospital cost. The described safety strategies have shown continuous improvement and “exemplary” (Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program [MBSAQIP] semi-annual report) status in patient outcomes at our center over several years

References

- Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academies Pr; 2000.

- Institute of Medicine (IOM). (2004). Keeping patients safe. Transforming the work environments of nurses. Washington, DC: The National Academic Press. https://www.iom.edu/reports/2003/Keeping-Patientss-Safe-Transforming-the-Work-Environment-of-Nurses.aspx. Accessed October 5, 2019.

- Weaver SJ, Lubomksi LH, Wilson RF, et al. Promoting a culture of safety as a patient safety strategy: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(5 Pt 2):369–374.

- National Patient Safety Foundation Safe Practices. www.npsf.org/for-healthcare-professionals/resource-center. Acccesed September 30, 2019.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. www.qualityindicators.ahrq.gov. Accessed September 30, 2019

- Armellino D, Walsh TJ, Petraitis V, Kowalski W. Assessment of focused multivector ultraviolet disinfection withshadowless delivery using 5-point multisided sampling ofpatientcare equipment without manual-chemical disinfection. Am J Infect Control. 2019;47(4):409–414.

- Institute for Patient-and-Family-Centered Care. (2010). FAQs. Institute for Patient-and-Family-Centered Care. www.ipfcc.org/faq.html. Accessed October 8, 2019.

- Wang Y, Eldridge N, Metersky ML, et al. National trends in safety for four common conditions, 2005-2011. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(4):341–351.

Category: Past Articles, Raising the Standard