Raising the Standard: Utilization of the Electronic Medical Record to Facilitate Quality Improvement

by Dominick Gadaleta, MD, FACS, FASMBS, and Anthony T. Petrick, MD, FACS, FASMBS

by Dominick Gadaleta, MD, FACS, FASMBS, and Anthony T. Petrick, MD, FACS, FASMBS

Dr. Gadaleta is Chair of the Department of Surgery at Southside Hospital and Director of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery at North Shore University Hospital, Northwell Health in Manhasset, New York; and Associate Professor of Surgery at Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell in Hempstead, New York. Dr. Petrick is the Quality Director at Geisinger Surgical Institute and Director of Bariatric and Foregut Surgery for Geisinger Health System in Danville, Pennsylvania.

Funding: No funding was provided for this article.

Disclosures: The authors reports no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Bariatric Times. 2019;16(6):10.

ADCA VAN DIMLS

Those of us of a certain age will remember using one mnemonic or another to remember admission orders. To some degree, ADCA VAN DIMLS was the original order set. The purpose was to teach medical students and house staff the essential and minimal orders necessary to properly admit a patient. The mnemonic ADCA stands for “admit” (to the service of), “diagnosis,” “condition,” and “allergies”, VAN for “vital signs,” “activity,” and “nursing;” and DIMLS for “diet,” “intravenous orders,” “medications,” “labs,” and “special.” The order of letters do not necessarily correspond to the order in which to complete these tasks, rather they are meant to faciliate easy memorization. Currently, there is much more information that needs to be conveyed, drawing from many sources. In this month’s column, we will explore the positive and negative aspects of the modern health record and review what can and is being done to facilitate quality and enhance patient safety.

Readers of this column are familiar with the 1999 report issued by the United States Institute of Medicine, “To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System,” which concluded that between 44,000 to 98,000 people die each year as a result of preventable medical errors.1 The subsequent report in 2001 titled “Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century,” which was also by the United States Institute of Medicine, provided a blueprint for preventing medical error by creating a patient-centered, information-sharing, “best evidence,” transparent, and cooperative healthcare environment.2 They envisioned the complete elimination of handwritten notes by 2010 as an example of a patient safety initiative that they felt was achievable with government intervention. Although we are not there yet, we have come a long way. For example, in New York, effective March 27, 2016, most of us no longer carry prescription pads, since practitioners are mandated to electronically prescribe both controlled and noncontrolled substances, with the only exceptions being temporary technological failure, temporary electrical failure, an approved waiver, if the practitioner reasonably determines that it would be impractical for the patient to obtain substances prescribed by electronic prescription in a timely manner, and such delay would adversely impact the patient’s medical condition, or to be dispensed by a pharmacy located outside the state.

In addition to preventing errors due to patient misidentification and illegible notes and orders, the electronic medical record (EMR) can provide valuable insight into care by providing an audit trail and full transparency, in real time, if needed, to evaluate less-than-perfect outcomes and near misses. It is infinitely better than paper charts for clinical research, data abstraction, and other activities where a chart review is employed. Ultimately, the desire for standardization and the need to meet regulatory requirements, such as meaningful use, have forced reluctant healthcare providers to forge forward.

Perhaps the most interesting use of the EMR to improve the quality of patient case lies in the field of advanced decision science.

Modified Early Warning System (MEWS)

In 2005, Kremsdorf3 estimated that 60,000 Medicare patients under the age of 75 die each year in failure-to-rescue situations. One of the newer ways to address this problem is leveraging the data inputted into the EMR to alert providers in real time that the patient might need additional resources.

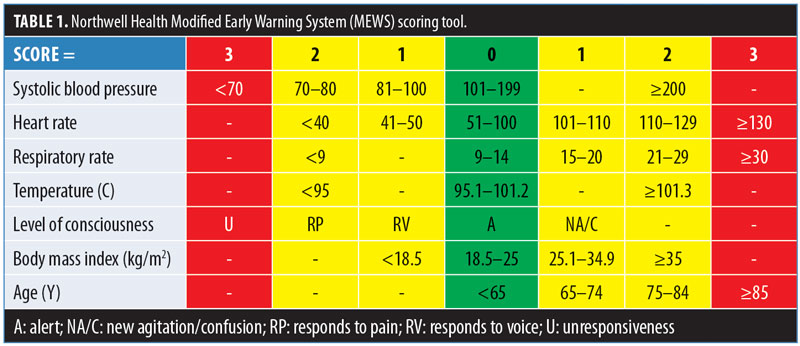

On December 2, 2016, Northwell Health implemented a patient safety algorithm that interfaces with the EMR to notify providers of early signs of deterioration in patients and to help determine the need for transfer to a higher level of care. This algorithm, called the Modified Early Warning System (MEWS), is a scoring tool that uses a 10-point scale for patient evaluation based on the following seven parameters: systolic blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, temperature, level of consciousness, body mass index (BMI), and age (Table 1). When a score of seven is achieved based on documentation in the EMR, providers are automatically alerted and prompted by the EMR to initiate a series of interventions, including sepsis screenings and shorter vital sign monitoring intervals. At a score of nine or greater, providers are prompted to consider calling a rapid response and to transfer the patient to a higher level of care. Today, all Northwell hospitals with EMR use MEWS.

Although formally implemented throughout the health system in 2016, Northwell Health began work on MEWS in the early 2000s, with modifications/enhancements being made along the way. There are now millions of MEWS scores recorded, and one future focus area is how this historical data might be used for clinical forecasting of patient decompensation. That is, converting a reactive early warning score into a proactive and anticipatory early warning system. Of course, to do this, the data must be entered in real time, with invasive and noninvasive monitors linked to the EMR. Unpublished analysis of the data has revealed earlier recognition and quicker transfer to a higher level of care, compared to the period before implementation. Maimonides, using the Brooklyn Early Warning System (BEWS), which is a combination of enabling technologies, automated scoring, algorithmic escalation, and changes in traditional workflow, found a 30-percent decrease in failure to rescue and a substantial reduction in mortality.4 Although not perfect, most would agree these efforts all leverage the EMR to improve quality of care and patient safety.

References

- Linda T. Kohn, Janet M. Corrigan, and Molla S. Donaldson, Editors; To err is human: Building a safer health system, Committee on Quality of Health, Care in America, Institute of Medicine. National Academy Press. Washington, DC. 1999.

- Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: A new health care system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. 2001.

- Kremsdorf R. Tackling the underlying problems of failure to rescue. The Hospitalist. https://www.the-hospitalist.org/hospitalist/article/122945/tackling-underlying-problems-failure-rescue. Updated March 2005. Accessed May 26, 2019.

- Shiloh AL, Lominadze G, Gong MN, Savel RH. Early warning/track-and-trigger systems to detect deterioration and improve outcomes in hospitalized patients. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2016; 37(1):88–95.

Category: Past Articles, Raising the Standard