Which Bariatric Surgery is Best for My Patient? Guiding Patients Toward Optimal Surgical Treatment for Obesity While Supporting Autonomy

by Gretchen E. Ames, PhD, ABPP; Matthew M. Clark, PhD, ABPP; Karen B. Grothe, PhD, ABPP; Maria L. Collazo-Clavell, MD; and Enrique F. Elli, MD

by Gretchen E. Ames, PhD, ABPP; Matthew M. Clark, PhD, ABPP; Karen B. Grothe, PhD, ABPP; Maria L. Collazo-Clavell, MD; and Enrique F. Elli, MD

Drs. Ames and Elli are with the Division of General Surgery, Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Florida. Drs. Clark and Grothe are with the Department of Psychiatry and Psychology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota. Dr. Collazo-Clavell is with the Department of Endocrinology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota.

Funding: No funding was provided for this article.

Disclosures: The author reports no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this manuscript.

Bariatric Times. 2018;15(11):18–27.

Abstract: The field of bariatric surgery has changed rapidly in the past two decades, and guiding patients toward the appropriate procedure for their clinically severe obesity is complex. Here, the authors review bariatric surgical procedure options, including sleeve gastrectomy, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, and biliopancreatic diversion with or without duodenal switch, evidence on procedure safety and efficacy, and other factors that can influence patient choice of one procedure over another.

Shared decision-making in the context of patients’ acceptance of treatment risk, medical problems, weight loss expectations, eating behaviors, and mental health are discussed along with reasons for undergoing bariatric surgery. Priorities of weight loss, such as type 2 diabetes resolution, play a role in surgical choice and assessment tools like the Individual Metabolic Surgery score exist to aid in selection of a procedure according to a patient’s diabetes severity.

Through a series of prepared medical visit vignettes, the authors provide insights for how providers might guide conversations about surgical choice with their patients, carefully balancing patient preference with their own perceptions of which bariatric surgery will result in optimal improvements in physical and mental health.

For the bariatric surgery integrated care team, guiding patients toward the most appropriate procedure for their medically complicated obesity is complex for several reasons. At present, there is a lack of patient treatment-matching models that fully incorporate medical comorbidities, psychiatric diagnoses, psychological factors, and patient preferences into evidence-based guidance for the best surgical option for the patient. Adding to the complexity of this is the ever-evolving options for surgical treatment of obesity. For example, the rapid rise in popularity of the sleeve gastrectomy (SG) and precipitous decline in laparoscopic adjustable gastric band (LAGB)—SG now comprises nearly 60 percent of all bariatric operations performed in the United States—is a reflection of the rapidly changing field of bariatric surgery.1 Further adding to the complexity of the decision-making process is patients’ access to health information on the internet and social media platforms, which is highly prevalent and might not always provide evidence-based recommendations.2 Finally, providers and patients might differ on how they prioritize outcomes after bariatric surgery. Providers might prioritize metabolic disease remission, body mass index (BMI; [kg/m2]) reduction, and surgical risk, while patients might be most concerned with improvements in quality of life and feeling in control of their health and well-being.3 Thus, providers must carefully balance patient preference with their own perceptions of which bariatric surgery will result in optimal improvements in physical and mental health because healthcare provider influence on surgical choice is crucial.4

The purpose of this article therefore is twofold. The first aim is to provide a review of the literature about what influences patient choice of one bariatric procedure over another in the context of acceptance of treatment risk, medical problems, weight loss expectations, eating behaviors and mental health, and desire for a secondary operation. The second aim is to provide insights for how providers might guide conversations about these topics with their patients through prepared medical visit vignettes. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) and SG will be discussed primarily in this article since LAGB is decreasing in popularity.1 Biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD-DS) will be discussed in the context of a secondary operation after SG when there is inadequate weight loss or remission of medical comorbidities. The single-anastomosis DS as a primary or secondary operation will not be discussed in this article because this procedure is relatively new; therefore, there is sparse empirical evidence regarding its long-term safety and efficacy.5

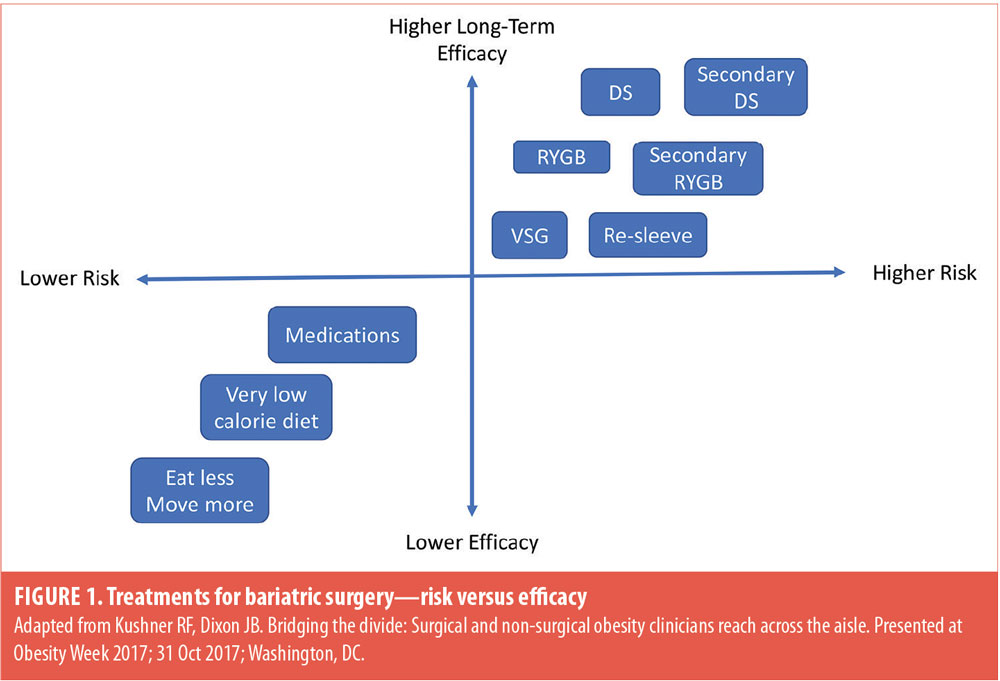

Treatment Efficacy versus Risk

Helping patients who have struggled with the chronic disease of obesity for many years understand that a continuum exists between treatment efficacy and potential risks associated with desired outcome is important. It has been well documented that the lowest risk treatments like lifestyle modifications (e.g., eat less and exercise more) are likely to be least effective in terms of magnitude and duration of weight loss and long-term remission of medical problems for most patients who suffer from medically complicated obesity.6 Similarly, treatments such as very low-calorie diets and medications might induce large weight loss and improvements in health in the short-term, but long-term maintenance of lost weight remains elusive. However, when talking to patients in a clinic, they often struggle with a longstanding internal dialog, such as “I should able to lose this weight on my own” and that surgery is “the easy way out” and/or not medically necessary.7 This narrative is often supported by providers who are not specialists in the treatment of obesity. A recent survey of primary care physicians and obesity medicine specialists regarding their understanding of biological and behavioral factors that contribute to obesity revealed two striking findings.8 First, primary care physicians rated behavioral factors rather than biological factors as the reason for weight regain after initial weight loss, and second, lifestyle modification was rated as a more effective in treating obesity compared to medications and bariatric surgery.

If patients maintain the belief that body weight is completely under volitional control and modifiable through diet and exercise alone, they might be less likely to accept that a greater level of risk (i.e., bariatric surgery) will be necessary to achieve the desired improvements in health, mobility, and quality of life. Likewise, patients might have difficulty accepting that a more invasive bariatric surgery might be necessary for remission of a medical condition, such as type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).9 Early in the evaluation process, the bariatric surgery team needs to assess and address patients’ knowledge of causes and contributing factors to their weight and any preconceived ideas they might have about bariatric surgery.7 The most common reasons patients self-remove from bariatric surgery programs after the initial information session are that they perceive bariatric surgery to be too invasive or risky and they have concerns about their ability to commit to the required lifestyle changes.10 Moreover, providers might need to help patients reframe their personal narrative about bariatric surgery in that it is a biological treatment of medical necessity and lower risk treatment options alone are likely to be ineffective even with their best efforts at lifestyle modification (Figure 1).7 Although patients will need to exert significant effort in terms of lifestyle change after bariatric surgery, the metabolic changes induced by the surgery will facilitate a higher likelihood of successful long-term outcome.11 Patients potentially will be rewarded with substantial weight loss, significant improvements in health and mobility, and reduced risk of weight regain when combined with lifestyle change.

A priority for the bariatric care team is to determine which operation is likely to have the highest efficacy in achieving remission of medical problems or preventing future medical problems with the lowest rates of morbidity and mortality.12 This must be balanced, however, with shared-decision making that considers patients’ values and goals like improving quality of life and feeling in control of health, mobility, and well-being.3 Moreover, providers should query patients’ reasons and motivations for or against having bariatric surgery and listen for preconceptions about surgical risk, inaccurate information, and anecdotal evidence of either success or poor response to bariatric surgery. A recent study investigating patients’ reasons for and against a particular bariatric surgery revealed there are differences between choice of RYGB compared to SG.4 Patients desiring RYGB cited the evidence of long-term effectiveness and success rate with weight loss, whereas patients who underwent SG cited their own research (e.g., internet, social media) as reason for choosing SG. Previous research has shown that approximately 78 percent of patients who are interested in bariatric surgery look for information on the internet and are particularly interested in the types of procedures and the experiences of other patients.2 Inevitably, health information viewed on the internet might vary in credibility and will be interpreted according to the depth of patients’ individual medical knowledge and comprehension. Another reason patients might choose SG is having personal contact with someone else who had successfully lost weight after this type of bariatric surgery.4 Perception of outcome for friends and family members might be greatly influenced by the availability of recent personal examples of positive or negative experience with bariatric surgery.13

Medical Problems

Arguably, one of the most important findings in metabolic and bariatric surgery research is that it is a more efficacious treatment for T2DM than medical therapy.14,15 Some patients are aware of bariatric surgery as a treatment for T2DM and might view remission of T2DM as more important than maximizing weight loss.16–18 Nevertheless, patients with T2DM will need in-depth guidance regarding disease severity. A recent study developed an Individual Metabolic Surgery score (IMS score; http://riskcalc.org/Metabolic_Surgery_Score/) to aid in selection of a procedure according to diabetes severity.9 To determine T2DM severity, providers will need to consider several presurgery risk factors, including duration of T2DM, glycemic control, number of medications, and insulin use. These risk factors are used to determine T2DM disease severity score, ranging from mild (IMS score <25), moderate (IMS score >25 but <95), and severe (IMS score >95). Overall, T2DM remission rates (i.e., hemoglobin A1c [HbA1c] below 6.5; off medications for 5 years after surgery; fasting blood glucose <126)19 were found to be significantly higher in patients who underwent RYGB (49%) compared to SG (28%) at five-year follow-up.9 The authors of the IMS score suggest that for mild disease severity (e.g., 1 medication; HbA1c<7; 3 years duration) either RYGB or SG will be effective treatments for T2DM; however, RYGB does result in higher rates of remission long-term. Therefore, if patients have favorable surgical risk-benefit ratio and are willing to consider RYGB, this operation might result in better long-term remission of T2DM. For patients who have moderate T2DM disease severity (e.g., 2 medications; HbA1c>7; 6 years duration), RYGB is recommended as ideal because it has a significantly higher rate of remission at five years compared to SG (60% vs. 25%, respectively). Possible explanations for T2DM disease remission are that there might be sufficient functional beta cell reserve together with neurohormonal effects associated with rerouting of the intestine with RYGB.20 For patients with severe T2DM (e.g., insulin; HbA1c>7; 15 years duration) where functional beta cell reserve is likely low, both operations are similarly effective, resulting in 12-percent disease remission at five years.9 Thus, SG—a lower risk operation21—might be the best choice for these patients if there is no other medical indication that RYGB would be a better choice (e.g., severe gastroesophageal reflux disease [GERD]).9,22

We recognize that DS has been shown to be the most effective operation for T2DM remission;23 however, this operation remains uncommon in the United States. The DS represented only 0.6 percent of the total number of bariatric surgeries performed in the United States in 2016.1 Vignette 1 presents a demonstration of conversation with a 55-year-old woman with a BMI of 45kg/m2 considering bariatric surgery as treatment for T2DM.

Vignette 1: Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass as Treatment for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

The patient: A 55-year-old woman presenting with body mass index of 45kg/m2 and three comorbid conditions—type 2 diabetes mellitus; obstructive sleep apnea; and hypertension; employed as a nurse; has no mental health history, and no current eating-disordered behaviors

Provider: I understand that you came in today because you are having some health issues and you want to learn more about bariatric surgery. What concerns you most about your health right now?

Patient: My diabetes. I am already taking two medications and my doctor told me the next step is insulin if I can’t get my hemoglobin A1c (A1c) down. It went up from 7.2 to 7.8 at my last visit. I really do not want to take insulin. I’ve tried for years to lose weight, but I just keep gaining and my diabetes is getting worse. Several of my coworkers had the sleeve procedure and they have done really well. One of them lost over 100 pounds and looks like a different person. That’s why I decided to make this appointment.

Provider: I can understand why you don’t want to be on insulin and that you are frustrated with not being able to lose weight despite multiple tries at dieting. At what age did you first start gaining weight?

Patient: Oh, I would say in my early 40s. I’ve never been small, but I really put weight on when I started working the night shift. I’m a nurse working on a cardiac unit.

Provider: Do you remember what your weight was before you started working nights?

Patient: That was a few years after my second child was born so probably 200 pounds. Now I’m 280 pounds and gaining. I have a lot more health problems, and I can’t get control of my weight, which worries me.

Provider: I see many patients who struggle with weight gain while working shift work. Sounds like you are ready to make some changes in your life if you are considering having bariatric surgery.

Patient: I would only ever consider the sleeve. I don’t want the big surgery—the gastric bypass. I have another coworker who did that one. She doesn’t look good, and I think she’s sick all the time. Although I don’t think she’s eating right. I’ve seen her in the cafeteria with fried foods.

Provider: There are differences between the sleeve gastrectomy (SG) and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB). We can spend some time talking today about what those differences are and which operation is likely to be most beneficial for you. How does that sound?

Patient: Honestly, I’ve never even considered the gastric bypass.

Provider: It’s common for patients to come in with an idea of which operation they want. There is a lot of information out there on the internet and social media and most patients I meet know someone who has had bariatric surgery. What I want to focus on first is your T2DM since you said that is your main health concern right now.

Patient: Yes, I would love to avoid needing to take insulin.

Provider: Both the SG and RYGB are effective treatments for T2DM. Both operations will result in lower HbA1c and reduce the number of T2DM medications you take probably within the first 3 to 6 months after surgery. There are good research studies comparing outcomes of SG to RYGB and which operation is best for long-term remission of T2DM. Remission means keeping your HbA1c below 6.5 ideally, without having to take medication.

Patient: My HbA1c has not been below 6.5 in a long time.

Provider: For someone like you with moderate disease severity (i.e., 6 years in duration, using 2 medications, and HbA1c>7; Individualized Metabolic Scale (IMS) score=73.2),9 RYGB is likely to be more effective in helping you achieve T2DM remission at least up to five years after the operation. Reasons for this might be that you still have enough cells in your pancreas that produce insulin. Rerouting the intestine with RYGB seems to have a powerful effect on hormones that stimulate insulin production to lower your blood sugar after eating.

Patient: Well, not having diabetes in five years does sound good. I just have never seriously considered gastric bypass. People who have that surgery look older and unhealthy to me.

Provider: There are many reasons people do well or poorly after bariatric surgery. Which operation you choose is not a decision you need to make today. Through the work-up process we can continue this discussion and address some of your concerns about RYGB if you want to seriously consider that operation. You don’t really have any other health issues that would make one operation more suitable over the other (e.g., gastroesophageal reflux disease, small bowel disease, solid organ transplant recipient/candidate).

Patient: Well, that’s good I guess.

Provider: So, some other factors beyond T2DM remission to consider before we meet again might be how much weight you desire to lose as RYGB tends to result in greater weight loss, your tolerance for risk as RYGB is a more invasive operation, and the quality of your diet. Some patients find the dumping syndrome associated with RYGB to be a powerful deterrent from eating sweets and processed foods. Nevertheless, whichever operation you choose, bariatric surgery is the most effective treatment we can offer for achieving remission of your T2DM.

Patients: I do like sweets even though they are bad for my diabetes. This is a lot to think about.

Provider: Indeed, do you think it would be helpful to come to our bariatric surgery support group and talk to patients who have already had SG or RYGB? They could potentially shed some light on how they made the choice between operations and you would have an opportunity to ask questions.

Patient: Yes, I think that would be very valuable to me in helping me better understand these two options.

Provider: Great, I’ll get you the date and time of our next bariatric support group meeting. At our follow-up visit we can talk about what you learned and anything else that might help you in deciding about which surgery will be the best tool to help you achieve your health goals.

There are medical conditions where one bariatric surgery might be a better choice over another. For patients who suffer from GERD, RYGB might be a better surgical choice because SG can make this problem worse in some patients.24 Possible mechanisms of action for an increase in reflux symptoms might be related to increased intragastric pressure with over narrowing of the gastric sleeve and decreased pressure of the lower esophageal sphincter.25,26 Vignette 2 presents a conversation with 49-year-old man with a BMI of 39kg/m2 and Barrett’s esophagus considering bariatric surgery for treatment of GERD. Conversely, there are certain medical conditions where SG might be the preferred operation, such as in individuals with small bowel disease. Both RYGB and SG appear to help patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis lose a significant amount of weight;27 however, previous bowel resections might be a contraindication for RYGB. Moreover, SG might be appropriate for other conditions where absorption of immunosuppressant medications is a concern as with solid organ transplant recipients28,29 or where maintenance of mood stability is concern with treatment-resistant psychiatric conditions.30 The bariatric care team should be aware that many patients have decided which operation they want prior to seeing a surgeon either from their own research or attendance at an information session.4,17 Thus, providers will need to engage patients in a thoughtful discussion regarding their willingness to consider an alternative operation if the operation they desire is not the best or safest choice given their individual medical history. Vignette 3 presents a conversation with a 65-year-old woman with a BMI of 47kg/m2 and fatty liver disease in work-up for liver transplant.

Vignette 2: Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass as Treatment for Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

The patient: A 49-year-old man; body mass index: 39kg/m2; gastroesophageal reflux disease; Barrett’s esophagus; sleep apnea; employed; married; no mental health history or current eating-disordered behaviors

Provider: Your gastroenterologist sent you over to talk about Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) as a possible treatment for your reflux. Is that your understanding of this appointment?

Patient: Honestly, I’ve never even considered surgery and was surprised when it was recommended to me.

Provider: It often takes years for patients to come to conclude that bariatric surgery is the best treatment option for them. It makes sense that you were a little caught off guard by the suggestion of RYGB for treatment of reflux. What are some things that we could talk about today that would be helpful to you?

Patient: Well, my doctor said weight loss would help with my reflux symptoms, which are pretty bad. I was hoping to be able to lose weight on my own. Is that an option?

Provider: Certainly. Most patients I meet have never given up on trying to lose weight. In fact, they have usually tried many diets, losing and regaining many pounds over the years. But yes, if you have not participated in a professionally lead weight loss program, that could be the first step.

Patient: That sounds like me, a weight cycler. I started gaining weight in my 30s with my first desk job. I’ve lost 50 pounds at least a couple of times.

Provider: Your experience is unfortunately pretty typical. It’s more common to regain lost weight than not. If 20 people who are at a high weight (body mass index [BMI]>35kg/m2) go on the same diet and lose 50 pounds or more, 19 of them will regain most, if not all, of the lost weight within a few years.

Patient: Really? Those are not very good odds.

Provider: It turns out that your weight—or really what we are talking about is how much body fat you have—(i.e., your set point) is not under your behavioral control as much as you might think. Your whole dieting life you have probably been told that if you eat less and exercise more, you can weigh whatever you want. That’s actually not true.

Patient: I’m not sure what you mean.

Provider: The human body is designed to store as much fat as possible and defend against fat loss in times of food scarcity. We now live in a 24-hour per day food environment where many people spend a lot of time during the day sitting. So, there is a mismatch between our biology and the environment we are now living in. An area in your brain called the hypothalamus regulates the amount of body fat you have through leptin signaling. Leptin is a hormone produced in your fat tissue that is involved with fat storage and satiety. When you go on a diet and start losing body fat, pretty quickly your hypothalamus senses that fat loss through seeing less of that leptin signal in your body. When your hypothalamus sees less leptin, it activates other biological processes that make you feel hungrier and less full and your body burns fewer calories during the day priming you to start regaining weight. This is your body’s way of preserving enough fat mass to ensure survival. The fancy word for it is metabolic adaptation to weight loss. Currently, our best tool to offset this powerful biological process is having bariatric surgery.

Patient: So, you are saying my body works against me when I try to lose weight.

Provider: That’s exactly right. There is no amount of will power that can overcome your brain’s desire to increase weight to what you weighed before you went on a diet. I have no doubt you can lose weight on your own, but keeping it off is very difficult because your biology is working against you.

Patient: So why does bariatric surgery work for some people?

Provider: Good question. Bariatric surgery or metabolic surgery involve alterations in your gastrointestinal track. These alterations change the physiological signals between your brain and gut to help lower how much fat your brain thinks is necessary for your body to survive. What you feel after surgery is actually the opposite of what you feel when you go on a diet, which is usually hunger and deprivation. After having bariatric surgery, you should feel less hungry and more full and satisfied even though you are eating smaller amounts of food. Your desire and cravings for foods high in fat, salt, and sugar should also decrease at least for the first year after an operation.

Patient: That sounds good, but I’m still not sure I understand.

Provider: Let me put some numbers to it. Your weight today is 290 pounds. Say 12 months after having bariatric surgery you lose down to 190 pounds. The hunger and fullness you feel will be appropriate for your new lower body weight and your brain will defend your fat mass at 190 pounds rather than trying to push your fat mass back up to your heaviest weight. Basically, your biology will be working with you rather than against you. Right now, bariatric surgery is the only treatment available that works on your biology in this way giving you the best chance of keeping weight off long-term.

Patient: That makes sense. I’ve never been able to maintain weight loss for more than a few months.

Provider: Right. That’s because of your biology, not lack of will power or self-discipline. If dieting in the way that you have before was going to work for you, it probably would have worked already.

Patient: I’ve never really thought about it like that before.

Provider: We haven’t talked yet about the anatomy of the RYGB and how it would help with your reflux. You said earlier that your symptoms are pretty uncomfortable. Would you like to know more about that?

Patient: Yes, that would be good.

Vignette 3: Sleeve Gastrectomy in Preparation for Liver Transplant

The patient: A 65-year woman; body mass index: 47kg/m2; nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; metabolic syndrome; retired; married; well managed depression

Provider: The liver transplant team referred you to us to talk about weight loss and possibly bariatric surgery if it is medically appropriate. A liver biopsy showed that your disease is pretty advanced, and they want you to lose weight so that you can be listed for transplant in the next year. Is that your understanding of the appointment today?

Patient: Yes, I already know I want gastric bypass. Both my husband and daughter have had it.

Provider: Oh good, so you already know a lot about bariatric surgery.

Patient: My husband had it 10 years ago. He’s gained a little weight back but not too much. My daughter is doing really well with hers.

Provider: If you choose to have bariatric surgery it would only be Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB)?

Patient: Yes.

Provider: What, if anything, do you know about other bariatric surgeries?

Patient: Not much. My niece had a sleeve. I guess she’s doing OK with it. But I am not really sure how she is doing.

Provider: There are some anatomical differences between the vertical sleeve gastrectomy (VSG) and the RYGB that might be relevant to your situation. That is, you might need liver transplant at some point in the future. Would you like to know more about the differences between VSG and RYGB?

Patient: I guess that would be good.

Provider: The VSG and RYGB are both what we call metabolic surgeries. What that means is they will change how your brain and gut communicate about what and how much to eat and how much body fat you store. However, there are differences that will be important for you to understand. RYGB involves rerouting or creating a shortcut in your intestines so that most of your stomach and part of your small intestine is bypassed. The part of the small intestine that is bypassed is where the immunosuppressant medications you take after transplant to keep your new organ healthy are absorbed. With the VSG, there is no rerouting of the intestine, so absorbing medication is less of a concern. Does that make sense to you?

Patient: Yes, I think so.

Provider: Together with the transplant team we have a lot of factors to consider in helping you choose the right operation. Did the transplant team talk to you about how much weight they would like you to lose before transplant?

Patient: They said they would like my BMI to be less than 40. I’m not sure how much weight that is.

Provider: So, your weight today was 285 pounds. To get below a BMI of 40 you would need to lose around 45 pounds. The good news is either VSG or RYGB could help you achieve this goal.

Patient: So how much weight would I lose with the sleeve?

Provider: Probably between 70 and 75 lbs. When was the last time you weighed in the low 200s?

Patient: Honestly, I can’t even remember. My daughter lost 120 pounds with RYGB. So, I won’t lose that much?

Provider: Probably not. With RYGB people generally lose 25 to 30 pounds more than with VSG. And your daughter is younger and able to be more active than you can be at this time, so those factors likely helped her lose more weight.

Patient: Well if I’m going to do this, I want to get the most weight loss.

Provider: I can understand that. Bariatric surgery requires a commitment to permanent changes in your lifestyle, and you want to get the most weight loss possible. Can I ask what success would look like to you in terms of your health status a year from now?

Patient: I don’t want to be so sick and need people to take care of me. The thought of that is very depressing.

Provider: I hear that a lot from patients. Maintaining your independence and being able to care for yourself is very important to you.

Patient: Definitely. My husband is already doing too much when I don’t feel well, and I feel guilty. When it’s time for a liver transplant, I need to be ready for it. Right now, I can’t even get on the list.

Provider: Would you be willing to consider VSG if it turns out to be a safer option for you after your bariatric surgery medical work up is complete?

Patient: I guess so.

Provider: Great. If you would like we can place all the orders we need to get the process started today.

Patient: Ok.

Weight Loss

For many patients seeking bariatric surgery, there will be an equivalent risk-to-benefit ratio to choose either RYGB or SG. A recent study investigated the influence of patient choice on outcomes after bariatric surgery. Results indicated that after evaluation by the bariatric team, 90 percent of patients were considered appropriate for any bariatric operation.31 The remaining 10 percent of patients were either appropriate for a certain operation due to extreme BMI, greater number of medical comorbidities associated with high perioperative risk, or were found to not be appropriate for any bariatric surgery. When patients have the freedom to choose their operation, there are other factors the bariatric care team should introduce into the conversation, such as expectations for weight loss. Patients frequently rate maximum weight loss as a priority when considering bariatric surgery, and they might be willing to assume more risk to achieve this goal.4,16,17 Therefore, providers should assess weight loss expectations for each individual patient, addressing potential misconceptions or inaccuracies given their choice of operation.

There is no way to predict exactly where an individual patients’ weight will settle 1 to 2 years after the having bariatric surgery. Weight loss outcomes will vary widely by procedure and from patient to patient in terms of weight loss and maintenance of lost weight after surgery.32 This uncertainty and lack of definitive numbers might be disconcerting for some patients. Healthcare providers should, therefore, calculate expected weight loss for the patients’ according to their preferred operation. Patients considering SG can expect to lose approximately 25 percent33,34 of their initial weight while patients considering RYGB can expect to lose approximately 32 to 35 percent of initial body weight in the first 12 months.14,34 Variables that have previously been shown to influence weight loss in the first year after surgery are age, sex, ethnicity, activity level, preoperative BMI, and medical comorbidities.14,33,35 For example, a patient who is older, sedentary, and deconditioned might lose less than expected 25 percent of initial weight after SG. Providers should discuss with patients their individual risk factors for both losing less weight in the first 12 months after the operation and risk factors for regaining lost weight beyond 12 months. These might include poor adherence to lifestyle change recommendations, chronic stress, injury and disability, lack of sleep, and use of weight-promoting medications.36

Patients’ unrealistic expectations for weight loss after having bariatric surgery are well-documented.37,38 Many patients believe they will lose more than the expected amount of weight based on what is consistently observed in the research literature. Anecdotally, we have observed in our patients that they have little understanding of the concept of metabolic adaption to weight loss. They might have a difficult time accepting that where their weight loss (or more appropriately fat mass loss) will ultimately settle is largely neurohormonally driven and not under behavioral control.39 Perhaps, patients’ reluctance to accept this idea is related to ubiquitous lifestyle change recommendations for weight loss—eat less and exercise more—which imply that weight loss is completely under volitional behavioral control.8 Patients have consistently heard the message from medical providers who are not specialists in obesity medicine that if they “work hard enough” at lifestyle change they can weigh whatever they desire, which unfortunately is not true for most patients struggling with medically complicated obesity. Therefore, if maximizing weight loss is the primary goal for a patient, he or she might need to consider an operation that has greater level of risk to achieve this goal (e.g., RYGB rather than SG or DS at extreme levels of BMI).

Eating Behavior and Mental Health

Maladaptive eating behaviors. Another factor to consider when patients do not have medical factors strongly indicating surgical selection is their eating behavior. Healthcare providers should discuss with patients aspects of their dietary intake that are going well, where there are areas for improvement, and what dietary changes will need to occur to optimize outcome after bariatric surgery. Recent research has demonstrated through neuroimaging, behavioral tests (e.g., unrestricted food access), and self-report measures that both RYGB and SG (at least in the short-term) result in decreased desire for highly palatable, energy-dense foods while improving maladaptive eating behaviors.18,40 Or, to state in nonclinical terms, most patients will experience less difficulty making healthy food choices because they will feel full and satisfied with smaller amounts of high-quality foods in the first year after bariatric surgery. For patients who have struggled with deprivation and increased hunger associated with dieting, neurohormonal changes after bariatric surgery will enhance their ability to make healthier food choices.11 However, the long-term durability of neurohormonal changes and improvements in maladaptive eating behaviors is less clear.11,41,42

Maladaptive eating behaviors like binge eating, loss of control over eating, grazing, (e.g., unplanned consumption of small amounts of food unrelated to hunger or satiety), night eating syndrome, and emotional eating in patients seeking both RYGB and SG are common.41–44 Bariatric surgery has a powerful effect on these behaviors as the frequency of maladaptive eating appears to decline during the first year and is associated with significant weight loss. However, recent research investigating eating patterns after RGYB and SG revealed that some patients will experience recurrence of maladaptive eating as early as four months after surgery and are at risk for poor weight loss or weight regain.42,45 Additionally, some patients without eating disordered problems before having bariatric surgery might develop new onset maladaptive eating behaviors that appear to negatively impact weight loss trajectory (i.e., weight regain after sufficient nadir weight loss) at 18 to 20 months after surgery.41

Taken together, these results suggest that providers should assess for problematic eating behaviors and distress associated with these behaviors at all bariatric surgery follow-up visits. Specifically, providers should inquire about grazing behavior and/or loss of control overeating as they might be associated with less-than-optimal weight loss outcomes and can develop after having bariatric surgery even in the absence of these behaviors before bariatric surgery.41 Moreover, eating disordered behaviors in the first postoperative year may be more important predictors of long-term maintenance of lost weight than preoperative eating pathology.41,45 Presently, there is not enough empirical evidence to support making a recommendation for either RYGB or SG based upon presurgery maladaptive eating behaviors.34 Based on our clinical experience, however, we do discuss the dumping syndrome associated with RYGB, which we find can be a powerful deterrent for some patients who struggle with the uncontrolled eating of sweets, high-fat foods, and highly processed low-quality food items. We also discuss that patients who undergo SG might be able to advance the postsurgical meal plan more quickly and resume consumption of calorie dense items that could attenuate weight loss in the first year.

Mental health. Similar to maladaptive eating behaviors, the prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities is high among patients seeking to have bariatric surgery, and some patients will experience significant mental health issues after having bariatric surgery.46,47 For example, some patients will develop alcohol use disorders48 and survivors of childhood sexual abuse might experience an increase in symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder.49 Some patients might experience increased symptoms of depression and risk of self-harm or suicide50,51 and antidepressant medications will need to be monitored closely after bariatric surgery.30 Possible reasons why some patients develop these problems after surgery while others do not might be associated with severity of presurgical psychiatric comorbidities, poor psychosocial adjustment to life after surgery, and the impact of neurohormonal changes induced by the surgery itself on mood that are presently not well understood. Therefore, how the presence of mental health comorbidities should influence the decision-making process for the type of bariatric surgery is also unclear and further clinical investigation in this area is needed. In our practice, SG is the preferred operation and is plausibly a safer choice for patients with a complex psychiatric and/or addiction history requiring psychotropic polypharmacy for management of symptoms.

Revision Operations

The number of revision operations performed in the United States is on the rise—from six percent in 2013 to 13.9 percent in 2016.1 LAGB has been largely abandoned in recent years as this procedure comprised only 3.4 percent of the operations performed in 2016 compared to 35.4 percent in 2011.1 Many patients who underwent LAGB in the past 15 to 20 years desire removal of the LAGB and conversion to either a VSG or RYGB. Problems with LAGB are related to either less-than-optimal weight loss or lack of remission of medical comorbidities. Problems caused by the LAGB itself include slippage, erosion, pouch dilatation, reflux, and vomiting/dysphagia.52 Either SG or RYGB might be appropriate secondary operations resulting in low complication rates, comparable weight loss outcomes, and improvements in T2DM, hypertension, and sleep apnea.52–54 Presently, there are no randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing outcomes of conversions to SG or RYGB after LAGB in terms of long-term weight loss or resolution of medical comorbidities.54 Moreover, a comprehensive literature search did not yield any studies investigating patient preference for SG or RYGB after less than optimal outcome with LAGB. In our population of patients who received LAGB who desire further treatment, RYGB is the preferred conversion operation. RYGB is indicated for patients who present with hiatal hernia, GERD, higher BMI, and might minimize risk of leak (compared to SG) at the previous LAGB location. When there is no medical indication for one operation over another, we suggest that providers engage in a shared decision with patients focused primarily upon their preferences of personal health and weight loss goals.

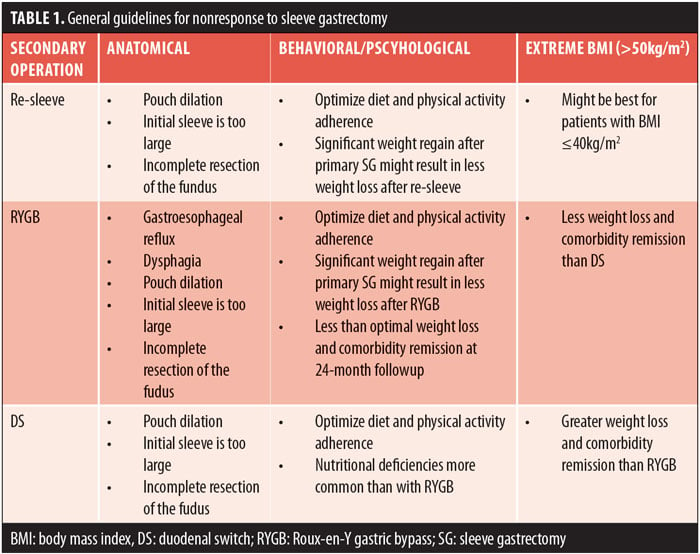

With the rise in popularity of the SG as a primary operation, patients who have less-than-optimal outcome, such as poor weight loss or insufficient resolution of medical problems, will need additional options for obesity treatment. Providers should view nonresponse to treatment after SG with the perspective that obesity is a chronic medical condition for which presently there is no cure, only behavioral, medical, and surgical strategies to help patients manage their weight. The need for further treatment should be expected for some patients and discussed without judgment and without the use of the words “treatment failure.”55 Nonresponse to obesity treatment is generally discussed in terms of insufficient weight loss and lack of remission of medical comorbidities. Specifically, lack of weight loss is often defined as less than 50 percent of excess body weight or BMI greater than 35kg/m2, including both lack of initial weight loss or sufficient weight loss with significant regain.56,57 Presently, there is no consensus on the choice of secondary operation after SG and the decision to perform a second operation is often based upon surgeon and medical center expertise rather than empirical evidence with long-term follow up.57 Furthermore, we were unable to find any studies investigating patient preference for type of secondary operation after SG. Previous research has shown that re-sleeve and RYGB are viable options for a secondary operation with comparable weight loss outcomes up to 24 months.56,58 However, in our clinical practice, re-sleeve is rarely indicated because of the potential for increased risk of leak and would only be considered if the primary operation was poorly performed with incomplete resection of the fundus. DS after SG appears to produce greater weight loss and higher rates of comorbidity remission compared to re-sleeve and RYGB,56,57,59 yet it might be most appropriate only for patients with extreme BMI. DS is associated with higher rates of nutritional problems compared to RYGB.59

When discussing a secondary operation, providers should consider the potential mechanism of action behind inadequate response to treatment, which might include anatomical, behavioral, psychiatric and psychological issues, use of weight-promoting medications, or extreme BMI. A factor to consider is the initial weight loss trajectory because it might have implications for successful weight loss after a secondary surgical procedure.60 It is important to assess if the patient experienced inadequate initial weight loss or experienced weight regain after initial successful weight loss. When weight regain is associated with poor adherence to recommendations for lifestyle change, any second operation might be less effective if lifestyle factors are not addressed. Therefore, adherence to recommendations for lifestyle change after bariatric surgery will need to be optimized prior to proceeding with any secondary operation. Patients will need to be informed that with any secondary operation, weight loss results and comorbidity resolution might be less than optimal.61 General guidelines to consider based on existing empirical evidence for re-sleeve, RYGB, and DS are presented in Table 1. Vignette 4 provides a discussion with a patient considering DS as a secondary operation after SG.

Vignette 4: Duodenal Switch after Sleeve Gastrectomy

The patient: A 50-year-old man; twi years post sleeve gastrectomy; presurgery body mass index: 62kg/m2; postsurgery body mass index: 48kg/m2; type 2 diabetes mellitus, hemoglobin A1c: 6.9 off insulin; hypertension; sleep apnea; depression

Provider: You are here for your two-year follow-up visit after sleeve gastrectomy (SG). What do you think about your progress so far in reaching your weight loss goals.

Patient: I’m really happy with the 100 pounds that I lost. To be honest, though, I thought I would lose more than that. I haven’t lost any weight for the past eight months.

Provider: Your weight before surgery was 460 pounds and now you are down to 350 pounds. That is about 24 percent of your weight, which is a reasonable amount of weight loss after VSG.

Patient: Yeah, we talked about what to expect with weight loss before I even had the sleeve, but I thought I could get to the low 300s at least.

Provider: Despite your best efforts with diet adherence and exercise, you haven’t been able to lose any more weight.

Patient: Mostly best effort I would say. My diet is pretty good. I’m still trying to get enough protein every day and I have not gone back to junk food or soda. I can’t eat too much at one time, which really helps.

Provider: That all sounds really good. With your consistent effort the surgery is doing just what it’s supposed to do. What about physical activity?

Patient: That’s a little bit harder. My knees are bad, and I can’t walk too far. Weight loss has helped, but they still hurt. I need a knee replacement, but the orthopedic doctor says I’m too young and still too heavy to do it.

Provider: Is there any exercise you can you do without too much pain?

Patient: I can use my swimming pool about eight months out of year, which is the best thing for my knees. I also have a gym membership where I can use the recumbent bike and lift weights. I try to go 4 to 5 times per week.

Provider: Seems like you are doing the best that you can despite having trouble with your knees.

Patient: I do sit at work all day, which doesn’t help, but I really have tried to do what I can to be active.

Provider: Yes that’s true, spending too much time in low energy behavior like sitting is not good for weight loss and can contribute to weight regain.

Patient: One thing I have been thinking about is asking my boss for a sit-to-stand desk.

Provider: That’s a great idea! I know you have a history of depression, so how is your mood doing?

Patient: My mood has been very stable now for a number of years.

Provider: I am glad to hear that. Another idea we can talk about is the possibility of a second operation to assist with more weight loss. Is that something you might like to know more about today?

Patient: I remember we talked about that when I first decided to have the sleeve, that I might need two operations. I really thought that I wouldn’t need to do that.

Provider: We often recommend a second operation when patients are doing really well with adherence to lifestyle change but their weight loss has stopped short of their goals for health and mobility.

Patient: So, would it be gastric bypass?

Provider: Either that or possibly a duodenal switch (DS), which might help you lose the most weight and put your diabetes completely in remission—that means off of all medicines and HbA1c less than 6.5.

Patient: Well, I did get off insulin, which I’m happy about, but I still have to take diabetes medication.

Provider: Taking oral medicine only is better than having to be on insulin, and your HbA1c has improved quite a bit since before your surgery.

Patient: I guess so. What’s the difference between gastric bypass and DS?

Provider: Good question. Both operations are what we call malabsorptive, and that term can sound scary to some patients. What it really means is that both operations create a short circuit or a shortcut in your small intestine. The small intestine is where most of the nutrients from the food you eat are absorbed. A shortcut means there is less area in the small intestine for nutrients to be absorbed and less of a common channel where your food and digestive juice mix together. The DS shortcuts more of the small intestine than the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) does. So that’s why with the DS there is a greater risk of problems with malnutrition. However, because there is less area for absorption of food with the DS, this might help you lose at least another 100 pounds and put your diabetes in remission. The RYGB might be less effective in terms of weight loss and diabetes remission. But, there are other risks and benefits to consider with DS. Would you like to know more?

Patient: Yes, I think so. I feel like I’m stuck with weight loss and don’t know what else to do. I have not weighed less than 300 pounds since my early 30s. But, nutritional problems don’t sound great either.

Provider: One thing that you have going for you is that you are very consistent with participating in all of your follow-up visits and taking good care of yourself. This would be extremely important if you decided to have a DS. You don’t have to make any decisions today. If you want, I can request a visit with your surgeon so that you can talk more about the risks and benefits and make sure you have a solid understanding of the anatomy of the DS.

Patient: Ok, that sounds good.

Conclusion

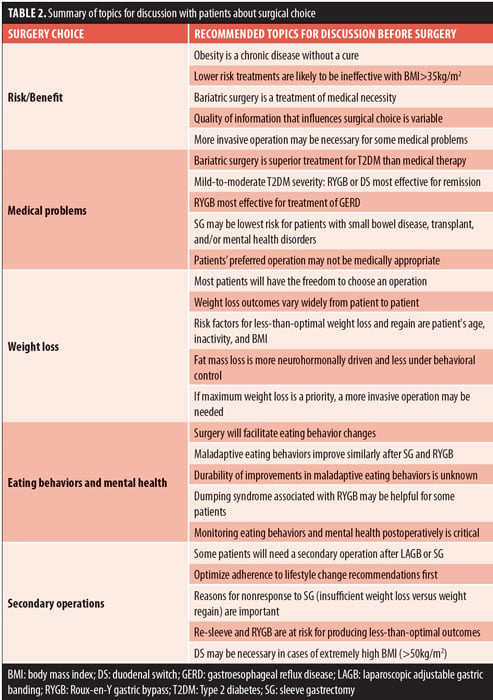

The field of bariatric surgery has changed rapidly in the past two decades, and guiding patients toward the appropriate procedure for their clinically severe obesity is complex. Many patients seeking bariatric surgery will have the freedom to choose in that after presurgery medical evaluation they are appropriate for any operation, and not one type of surgery has a clear advantage for optimal outcome. This decision can be complicated by patients having ready access to information of variable quality on the internet and their interpretation of the postsurgical experience of friends and family members. We have presented topics for discussion with patients and the associated research findings including risk/benefit profile, comorbidities, weight loss, eating behavior and mental health, and desire for a secondary operation given the rapid rise in popularity of the SG. These topics are important for discussion so that patients, collaboratively with their bariatric care team, can arrive at a shared decision about a bariatric surgery that supports patients’ goals, preferences, and autonomy (Table 2).

References

- English WJ, DeMaria EJ, Brethauer, et al. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery estimation of metabolic and bariatric procedures performed in the United States in 2016. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018;14(3):259–263.

- Paolino L, Genser L, Fritsch S, et al. The web-surfing bariatric patient: the role of the internet in the decision-making process. Obes Surg. 2015;25(4):738–743.

- Coulman KD, Howes N, Hopkins J, et al. A comparison of health professionals’ and patients’ views of the importance of outcomes of bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2016;26(11):2738–2746.

- Opozda M, Wittert G, Chur-Hansen A. Patients’ reasons for and against undergoing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, adjustable gastric banding, and vertical sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13(11):1887–1896.

- Kim J, American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Clinical Issues Committee. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery statement on single-anastomosis duodenal switch. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12(5):944–945.

- MacLean PS, Wing RR, Davidson T, et al. NIH working group report: Innovative research to improve maintenance of weight loss. Obesity. 2015;23(1):7–15.

- Trainer S, Benjamin T. Elective surgery to save my life: rethinking the “choice” in bariatric surgery. J Adv Nurs. 2017;73(4):894–904.

- Tsai AG, Remmert JE, Butryn ML, et al. Treatment of obesity in primary care. Med Clin North Am. 2018;102(1):35–47.

- Aminian A, Brethauer SA, Andalib A, et al. Individualized metabolic surgery score: procedure selection based on diabetes severity. Ann Surg. 2017;266(4):650–657.

- Yang K, Zhang B, Kastanias P, et al. Factors leading to self-removal from the bariatric surgery program after attending the orientation session. Obes Surg. 2017;27(1):102–109.

- Alamuddin N, Vetter ML, Ahima RS, et al. Changes in fasting and prandial gut and adiposity hormones following vertical sleeve gastrectomy or Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: an 18-month prospective study. Obes Surg. 2017;27(6):1563–1572.

- Castagneto Gissey L, Casella Mariolo JR, Mingrone G. How to choose the best metabolic procedure? Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2016;18(7):43.

- Saposnik G, Redelmeier D, Ruff CC, Tobler PN. Cognitive biases associated with medical decisions: a systematic review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2016;16(1):138.

- Courcoulas AP, Christian NJ, Belle SH, et al. Weight change and health outcomes at 3 years after bariatric surgery among individuals with severe obesity. JAMA. 2013;310(22):2416–2425.

- Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP, et al. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes—5-year outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(7):641–651.

- Apovian CM, Huskey KW, Chiodi S, et al. Patient factors associated with undergoing laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding vs Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for weight loss. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217(6):1118–1125.

- Weinstein AL, Marascalchi BJ, Spiegel MA, et al. Patient preferences and bariatric surgery procedure selection; the need for shared decision-making. Obes Surg. 2014;24(11):1933–1939.

- Holsen LM, Davidson P, Cerit H, et al. Neural predictors of 12-month weight loss outcomes following bariatric surgery. Int J Obes (Lond). 2018;42(4):785–793.

- Buse JB, Caprio S, Cefalu WT, et al. How do we define cure of diabetes? Diabetes Care. 2009;32(11):2133–2135.

- Lee WJ, Hur KY, Lakadawala M, et al. Predicting success of metabolic surgery: age, body mass index, C-peptide, and duration score. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2013;9(3):379–384.

- Hutter MM, Schirmer BD, Jones DB, et al. First report from the American College of Surgeons Bariatric Surgery Center Network: laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy has morbidity and effectiveness positioned between the band and the bypass. Ann Surg. 2011;254(3):410–420; discussion 420–422.

- Nelson LG, Gonzalez R, Haines K, et al. Amelioration of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for clinically significant obesity. Am Surg. 2005;71(11):950–953; discussion 953–954.

- Sudan R, Maciejewski ML, Wilk AR, et al. Comparative effectiveness of primary bariatric operations in the United States. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13(5):826–834.

- Nadaleto BF, Herbella FA, Patti MG. Gastroesophageal reflux disease in the obese: Pathophysiology and treatment. Surgery. 2016;159(2):475–486.

- Daes J, Jimenez ME, Said N, et al. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux can be reduced by changes in surgical technique. Obes Surg. 2012;22(12):1874–1879.

- Braghetto I, Lanzarini E, Korn O, et al. Manometric changes of the lower esophageal sphincter after sleeve gastrectomy in obese patients. Obes Surg. 2010;20(3):357–362.

- Shoar S, Shahabuddin Hoseini S, Naderan M, et al. Bariatric surgery in morbidly obese patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13(4):652–659.

- Rogers CC, Alloway RR, Alexander JW, et al. Pharmacokinetics of mycophenolic acid, tacrolimus and sirolimus after gastric bypass surgery in end-stage renal disease and transplant patients: a pilot study. Clin Transplant. 2008;22(3):281–291.

- Elli EF, Gonzalez-Heredia R, Sanchez-Johnsen L, et al. Sleeve gastrectomy surgery in obese patients post-organ transplantation. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12(3):528–534.

- Cunningham JL, Merrell CC, Sarr M, et al. Investigation of antidepressant medication usage after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2012;22(4):530–535.

- Vasas P, Nehemiah S, Hussain A, et al. Influence of patient choice on outcome of bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2018;28(2):483–488.

- Courcoulas AP, King WC, Belle SH, et al. Seven-year weight trajectories and health outcomes in the Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (LABS) Study. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(5):427–434.

- Maciejewski ML, Arterburn DE, Van Scoyoc L, et al. Bariatric surgery and long-term durability of weight loss. JAMA Surg. 2016;151(11):1046–1055.

- Ames GE, Heckman MG, Diehl NN, et al. Guiding patients toward the appropriate surgical treatment for obesity: should presurgery psychological correlates influence choice between Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and vertical sleeve gastrectomy? Obes Surg. 2017;27(10):2759–2767.

- Elli EF, Gonzalez-Heredia R, Patel N, et al. Bariatric surgery outcomes in ethnic minorities. Surgery. 2016;160(3):805–812.

- Kaplan LM, Seeley RJ, Harris J. Myths associated with obesity and bariatric surgery: Myth 1: Weight can be reliably controlled by voluntarily adjusting energy balance though diet and exercise. Bariatric Times. 2012;9(5):12–13.

- Heinberg LJ, Keating K, Simonelli L. Discrepancy between ideal and realistic goal weights in three bariatric procedures: who is likely to be unrealistic? Obes Surg. 2010;20(2):148–153.

- Wee CC, Hamel MB, Apovian CM, et al. Expectations for weight loss and willingness to accept risk among patients seeking weight loss surgery. JAMA Surg. 2013;148(3):264–271.

- Ochner CN, Barrios DM, Lee CD, Pi-Sunyer FX. Biological mechanisms that promote weight regain following weight loss in obese humans. Physiol Behav. 2013;120:106–113.

- Hansen TT, Jakobsen TA, Nielsen MS, et al. Hedonic changes in food choices following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2016;26(8):1946–1955.

- Conceição EM, Mitchell JE, Pinto-Bastos A, et al. Stability of problematic eating behaviors and weight loss trajectories after bariatric surgery: a longitudinal observational study. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13(6):1063–1070.

- Nasirzadeh Y, et al. Binge eating, loss of control over eating, emotional eating, and night eating after bariatric surgery: Results from the Toronto Bari-PSYCH Cohort Study. Obes Surg. 2018;28(7):2032–2039.

- Mitchell JE, King WC, Courcoulas A, et al. Eating behavior and eating disorders in adults before bariatric surgery. Int J Eat Disord. 2015;48(2):215–222.

- Goodpaster KP, Marek RJ, Lavery ME, et al. Graze eating among bariatric surgery candidates: prevalence and psychosocial correlates. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12(5):1091–1097.

- Ivezaj V, Kessler EE, Lydecker JA, et al. Loss-of-control eating following sleeve gastrectomy surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13(3):392–398.

- Mitchell JE, Selzer F, Kalarchian MA, et al. Psychopathology before surgery in the longitudinal assessment of bariatric surgery-3 (LABS-3) psychosocial study. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2012;8(5):533–541.

- Fisher D, Coleman KJ, Arterburn DE, et al. Mental illness in bariatric surgery: A cohort study from the PORTAL network. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2017;25(5):850–856.

- King WC, Chen JY, Courcoulas AP, et al. Alcohol and other substance use after bariatric surgery: prospective evidence from a U.S. multicenter cohort study. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13(8):1392–1402.

- Clark MM, Hanna BK, Mai JL, et al. Sexual abuse survivors and psychiatric hospitalization after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2007;17(4):465–469.

- Morgan DJ, Ho KM. Incidence and risk factors for deliberate self-harm, mental illness, and suicide following bariatric surgery: a state-wide population-based linked-data cohort study. Ann Surg. 2017;265(2):244–252.

- Bhatti JA, Nathens AB, Thiruchelvam D, et al. Self-harm emergencies after bariatric surgery: a population-based cohort study. JAMA Surg. 2016;151(3):226–232.

- Carr WR, Jennings NA, Boyle M, et al. A retrospective comparison of early results of conversion of failed gastric banding to sleeve gastrectomy or gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2015;11(2):379–384.

- Barreto SG, Chisholm J, Schloithe A, et al. Outcomes of two-step revisional bariatric surgery: reasons for the gastric banding explantation matter. Obes Surg. 2018;28(2):520–525.

- Sharples AJ, Charalampakis V, Daskalakis M, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes after revisional bariatric surgery following a failed adjustable gastric band. Obes Surg. 2017;27(10):2522–2536.

- Sogg S, Grupski A, Dixon JB. Bad words: Why language counts in our work with bariatric patients. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018;14:682–692.

- Cheung D, Switzer NJ, Gill RS, et al. Revisional bariatric surgery following failed primary laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: a systematic review. Obes Surg. 2014;24(10):1757–1763.

- Shimon O, Keidar A, Orgad R, et al. Long-term effectiveness of laparoscopic conversion of sleeve gastrectomy to a biliopancreatic diversion with a duodenal switch or a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass due to weight loss failure. Obes Surg. 2018;28(6):1724–1730.

- Nedelcu M, Noel P, Iannelli A, Gagner M. Revised sleeve gastrectomy (re-sleeve). Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2015;11(6):1282–1288.

- Homan J, Betzel B, Aarts EO, et al. Secondary surgery after sleeve gastrectomy: Roux-en-Y gastric bypass or biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2015;11(4):771–777.

- AlSabah S, Alsharqawi N, Almulla A, et al. Approach to poor weight loss after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: re-sleeve vs. gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2016;26(10):2302–2307.

- Nevo N, Abu-Abeid S, Lahat G, et al. Converting a sleeve gastrectomy to a gastric bypass for weight loss failure—is it worth it? Obes Surg. 2018;28(2):364–368.

Category: Commentary, Past Articles