Simultaneous Laparoscopic Ventral Hernia Repair and Bariatric Surgery: Case Series Report with Video

by Enrique Arias, MD, FACS; Francisco Ruiz, MD; Mario Urquiza, MD; and Gustavo Portillo, MD

by Enrique Arias, MD, FACS; Francisco Ruiz, MD; Mario Urquiza, MD; and Gustavo Portillo, MD

Drs. Arias, Ruiz, Urquiza, and Portillo are with Obesity El Salvador in San Salvador, El Salvador.

FUNDING: No funding was provided.

DISCLOSURES: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

ABSTRACT: Background. Morbid obesity is an important risk factor for the development of primary and recurrent ventral hernias. It is not unusual for patients with severe obesity to be required to undergo some weight loss before elective ventral hernia repair can be performed. We report our experience performing laparoscopic bariatric surgery with simultaneous ventral hernia repair (VHR).

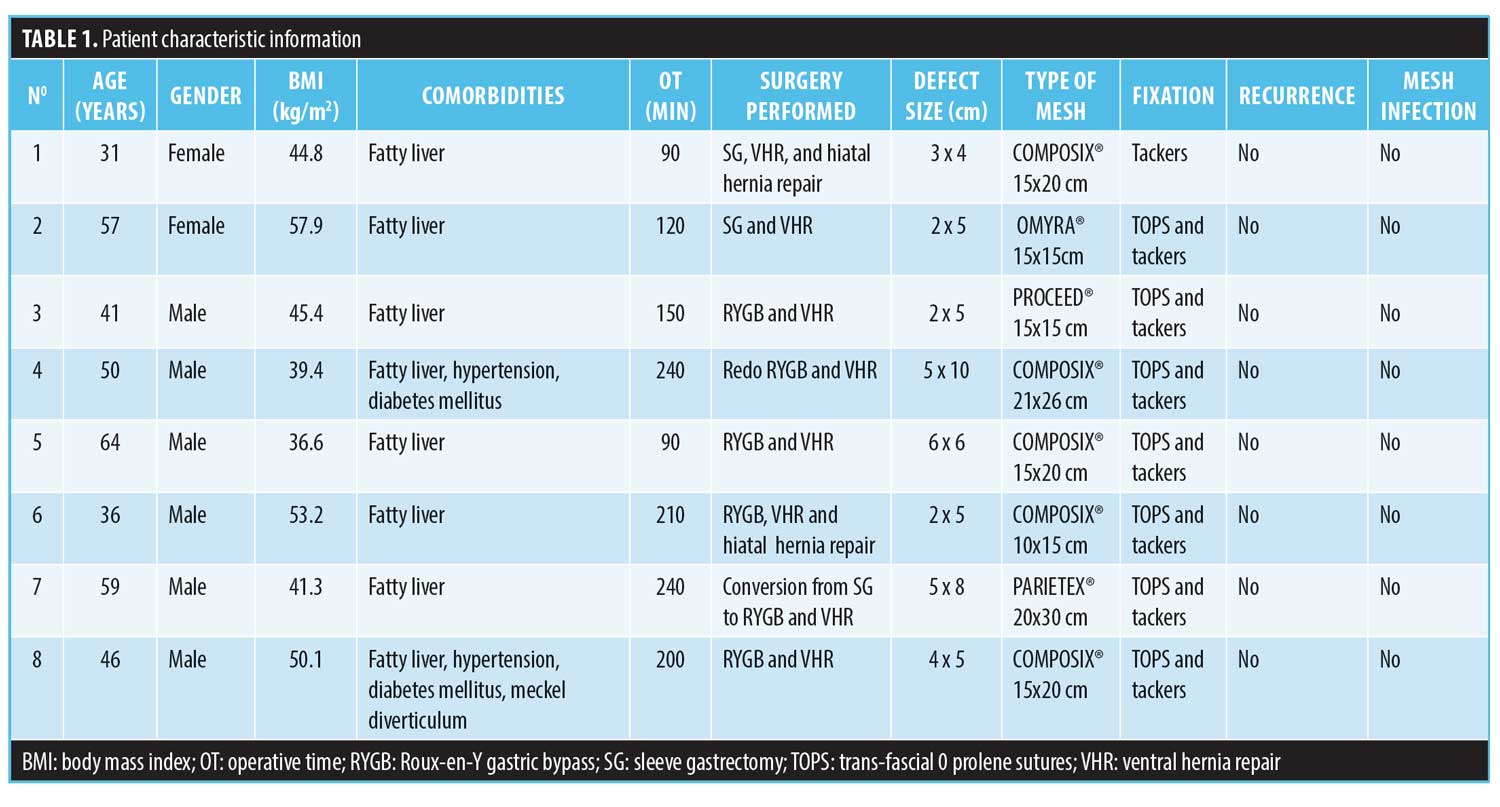

Methods. This is a retrospective observational study of patients who underwent laparoscopic VHR and bariatric surgery at Obesity El Salvador from 2011 to 2017. We studied demographic variables, hernia defect size, comorbidities, surgery time, type of bariatric procedure, hernia repair strategy, and postoperative complications. At least one year of follow-up was required.

Results. Between the 2011 and 2017, eight patients underwent laparoscopic bariatric surgery with simultaneous VHR. Two underwent sleeve gastrectomy (SG), four Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, and two revisional bariatric procedures. Of this cohort, 71.4 percent of the patients were male and 28.6 percent were female. The average age was 46 years (31–64), and the average body mass index (BMI) was 46.1kg/m2 (36.6–57.9). The defect size ranged from 3x4cm to 5x10cm, the mean operative time was 168 minutes (90–240 minutes). The hernia repair technique in all those cases was intraperitoneal onlay mesh (IPOM).

Discussion. Many surgeons prefer to avoid performing a hernia repair with a synthetic mesh at the same time as performing a bariatric surgery because it can increase the infection and recurrence rates; however, we show evidence showing safety performance of both procedures at the same time without an increase in the complications rate.

Conclusion. The repair of ventral hernia with synthetic mesh concomitantly to bariatric surgery is feasible, and it offers safety in terms of infections. The risk of hernia incarceration and small bowel obstruction after leaving an unrepaired small hernia defect during a bariatric procedure is high and could be questionable.

KEYWORDS: ventral hernia repair, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), intraperitoneal onlay mesh (IPOM), obesity

Bariatric Times. 2020;17(5):12–14

Morbid obesity is an important risk factor for the development of primary and recurrent ventral hernias. This is predominantly related to the chronically elevated intra-abdominal pressures secondary to obesity.1,2 Laparoscopic ventral hernia repair (VHR) with intraperitoneal onlay mesh (IPOM) can now be accepted as the primary method of treatment of ventral hernias in patients with obesity.3 Most surgeons consider that patients with severe obesity should undergo some weight loss before elective VHR.4 Several studies have reported on a successful two-stage strategy performing bariatric surgery first followed by deferred VHR. The main drawback to this approach is the risk of small-bowel obstruction through an unrepaired small hernia defect, associated with the rapid weight loss, with potential disruption of staple lines and consequently an abdominal disaster.

Recent analyses demonstrated that nearly 60 percent of patients undergoing abdominal wall hernias in the United States (US) had obesity.5,6 With the dramatic association between obesity, wound complications, and risk for hernia recurrence, patients with severe obesity and abdominal wall hernias represent a significant and increasingly common challenge for surgeons. Therefore, ventral hernias are not rare in the bariatric population; in fact, currently, eight percent of patients undergoing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) have a ventral hernia.7 Their management is technically demanding and remains controversial. Although the preferred method of hernia repair involves a tension-free technique using a prosthetic mesh, there is concern about potential infection using this method due to risk of the mesh becoming contaminated through contact with contents of the gastrointestinal tract. Thus, some surgeons prefer using biological mesh over prosthetic mesh or choose primary repair, but these management techniques are associated with higher rates of recurrences.2

Recent studies report the safe use of synthetic mesh in contaminated fields,8 and the updated guidelines of the World Society of Emergency Surgery recently published evidence 1A on emergency repair of complicated abdominal hernias, reporting that prosthetic repair with synthetic mesh can be performed without an increase in 30-day wound-related morbidity.9

We would like to report our experience performing laparoscopic bariatric surgery with simultaneous VHR with synthetic mesh.

Objective

The objective of this study was to determine the outcomes of simultaneous laparoscopic bariatric surgery and VHR with synthetic mesh.

Methods

This is a retrospective observational study of patients who underwent laparoscopic VHR and bariatric surgery at Obesity El Salvador from January 2011 to December 2017. The cases studied were included according to the following criteria: patients undergoing simultaneous laparoscopic VHR and bariatric surgery (laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy [SG], RYGB, revisional bariatric procedures, such as conversion from SG to RYGB) in Obesity El Salvador by any members of our surgery team, according to the team’s prospective management protocols. We studied demographic variables (sex, age, and body mass index [BMI]), hernia defect size, comorbidities, surgery time, type of bariatric procedure, hernia repair strategy (mesh type and fixation), peri- and postoperative complications. We obtained the informed consent of all patients included in this study for access to their clinical records. To be included in this study, a one-year minimum follow-up was required.

Surgical Technique

All patients received a prophylactic antibiotic. We routinely use single preoperative intravenous 1g of cefazolin, according to our institutional antibiotic policy. The technique of hernia repair was IPOM or IPOM+. Our first port is introduced using the OPTIVIEW® trocar (Johnson & Johnson, New Brunswick, New Jersey, USA), a 15mmHg pneumoperitoneum is used, and the rest of the trocars are placed under direct vision. We intend to use the same five trocar positions that we use in bariatric surgery alone, and we use 1 to 3 additional 5mm trocars if they are necessary for a better approach to the hernia.

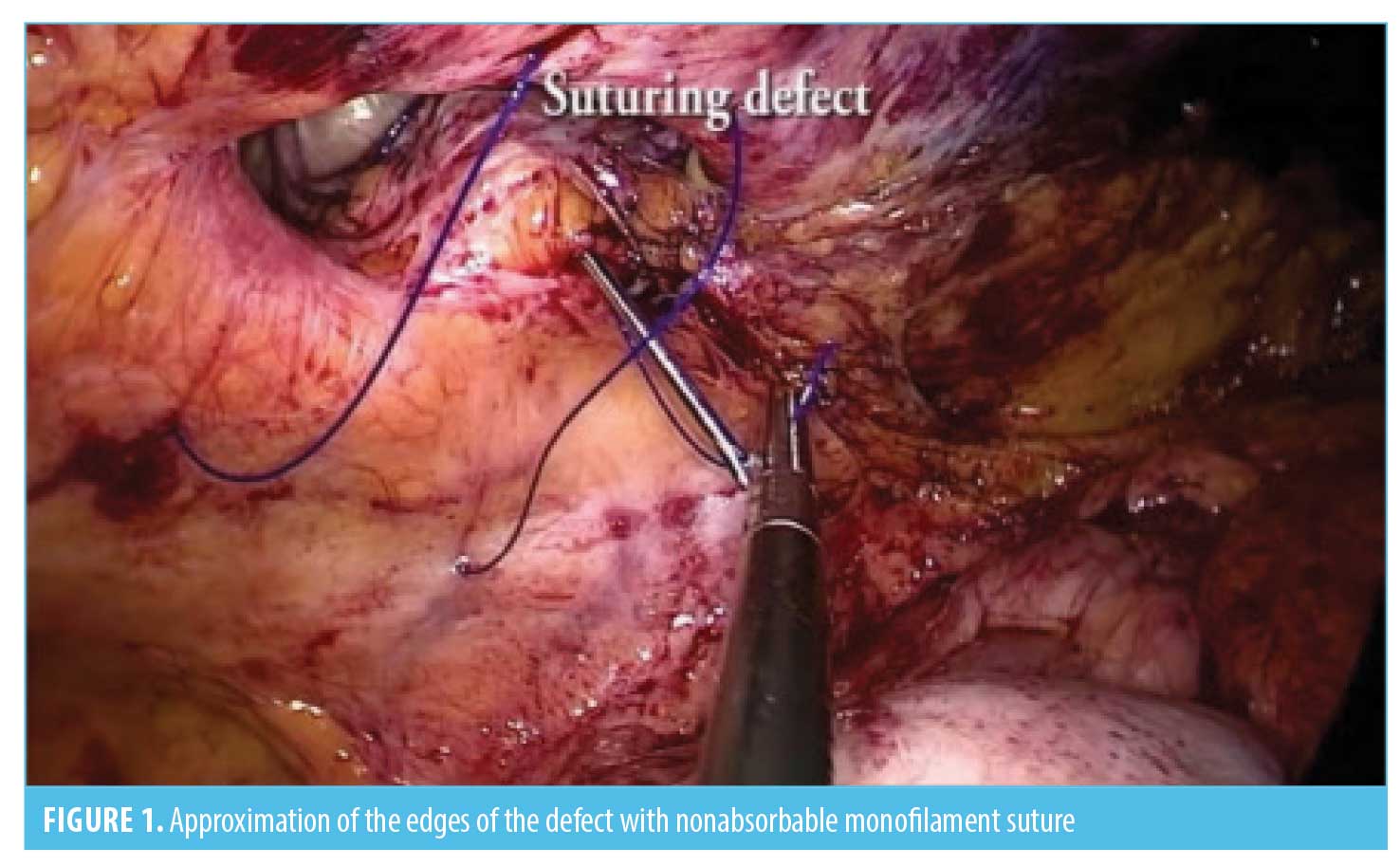

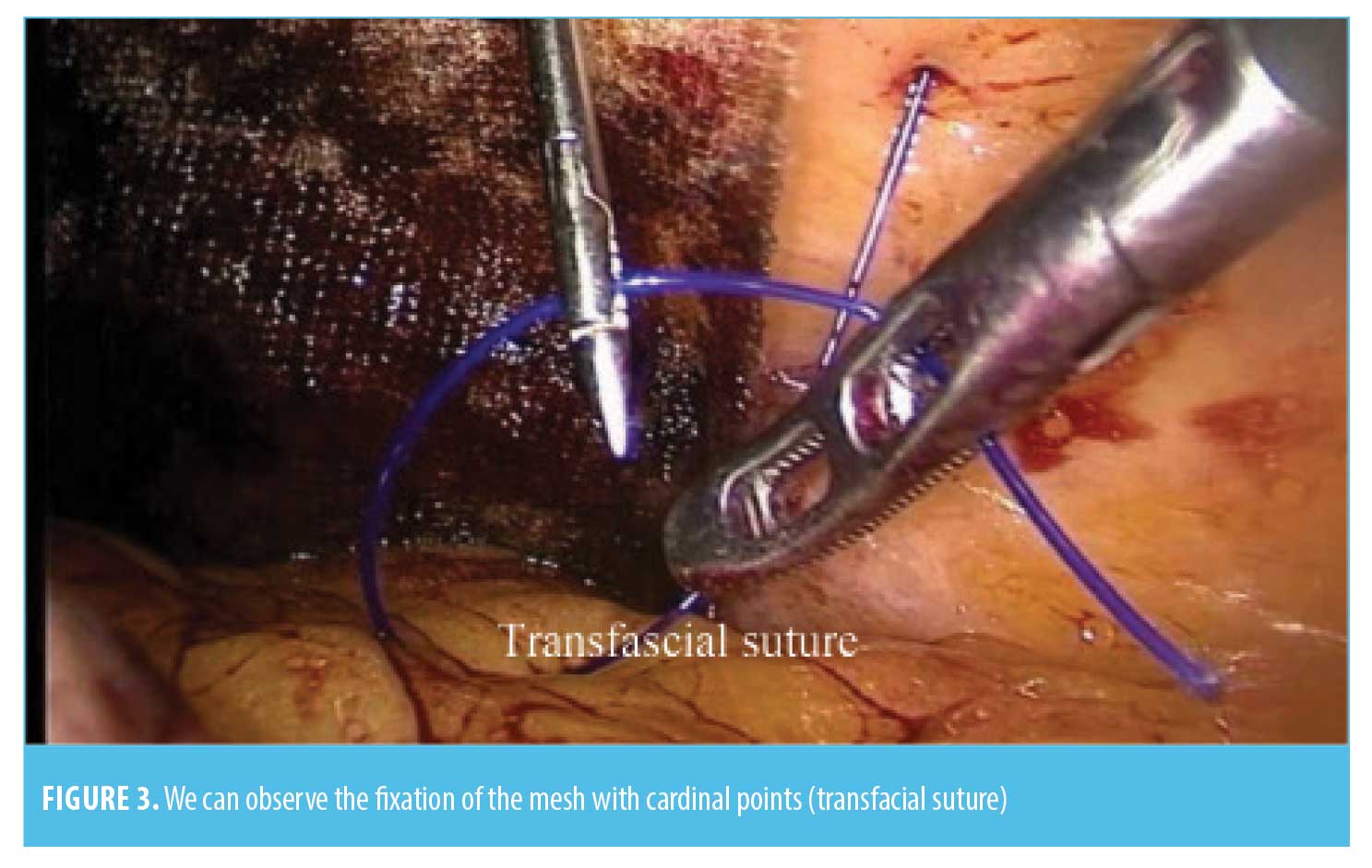

Our first step of the surgery is the adherolysis and reduction of the hernial sac contents. We use the harmonic scalpel to cut down the adhesions. The second step is to perform the bariatric procedure—the SG is performed over a 40 F Bougie, starting at 3cm proximal to the pylorus, using two green and 3 to 5 blue 60mm lineal staples. We routinely reinforce the staple line with 2-0 PDS suture, and the stomach is taken out without a specimen retrieval bag; In the gastric bypass, we leave a 30 to 50 mL vertically oriented gastric pouch, performing an antecolic antegastric RYGB with a 100 to 150cm biliopancreatic limb and a 75 to 150cm of alimentary limb. Gastrojejunostomy is created with a 30×3.5mm linear staple and closed with 2-0 PDS suture over a 36 F bougie. The jejunojejunostomy is performed with a 60×2.5mm linear staple, closed with a 3-0 PDS suture. Mesenteric and Petersen defects are routinely closed with a 2-0 polyester suture; in the revisional procedure from RYGB to RYGB, we trim the gastric pouch if it is dilated, and the gastrojejunostomy is completely taken down from the previous one and redone using the same technique as in the primary procedure. Finally, we cut down the alimentary limb close to the jejunojejunostomy and move it distal over the common channel to prolong the biliopancreatic limb and shorten the common limb, usually to 2m, using the same jejunojejunostomy and defects closure procedures; the usual revisional procedure from SG to RYGB we perform is extracting the gastric fundus after creating the new gastric pouch to avoid ischemia—the rest of the procedure is performed as in the primary RYGB. The third step is the hernia repair; usually we use a coated synthetic mesh or PTFE-c mesh, using the previously placed working trocars as far as possible. For big hernia defects, we place 1 to 3 additional 5mm trocars. The defects are closed with two or three suture transfascial of polypropylene 0 (Figure 1). When defects can not be closed without any undue tension, larger or “Swiss-cheese” type of defects will not be closed. This is followed by a placement of a mesh covering the defect all around for at least 5cm, anchored to the anterior abdominal wall by tackers and transfascial suturing (Figures 2 and 3). The specific meshes are shown in Table 1. The type of mesh was determined according to the availability at our institution and the size of the defect, in such a way that it covered the size of the defect and extended at least 5cm from the edges. Finally, we routinely place a 19 F silicone rounded drain as we do during bariatric surgery without hernia repair.

Results

Between 2011 and 2017, eight patients underwent LBS with simultaneous laparoscopic VHR. Two patients underwent SG, four RYGB, one conversion from SG to RYGB, and one revisional RYGB to RYGB. The breakdown by sex was 71.4 percent male and 28.6 percent female. The average age was 46 years (31–64 years). The average BMI was 46.1kg/m2 (36.6–57.9kg/m2). The defect size ranged from 3x4cm to 5x10cm, and the mean operative time was 168 minutes (90–240 minutes). The hernia repair technique in all those cases was IPOM using coated mesh in six cases, and in one case, we used a PTFE-c. Six procedures were performed using transfascial sutures and tackers fixation, and one was performed using only tackers fixation because a suturing device was not available. No recurrences nor mesh infections were reported. One patient underwent a postoperative haematoma (Table 1).

Discussion

Simultaneous laparoscopic VHR and bariatric surgery is a polemic topic. Many surgeons prefer to avoid performing a hernia repair with a synthetic mesh at the same time as performing a bariatric surgery because it is still considered that this can increase the infection and recurrence rates; however, we have evidence showing safe performance of both procedures at the same time without an increase in the complications rate. Lazzati et al2 suggest that treating hernia defects at the same time as bariatric surgery is feasible and safe. In a systematic review done by that group, it states that mortality was zero and overall early reoperation rate was 1.8 percent. The use of nonabsorbable synthetic mesh has the best results in terms of avoiding hernia recurrence, and it does not increase mesh infections.8–10 These results are controversial because bariatric surgery is considered a clean contaminated procedure, and traditionally it is a contraindication to employ a synthetic mesh, but it could be questionable. Cozacov et al11 compared surgical field contamination after RYGB and SG and found that the intraperitoneal bacterial cultures in patients undergoing SG were negative, and only 15 percent undergoing RYGB had bacterial growth. On the other hand, we have 1A evidence that prosthetic repair with synthetic mesh can be performed without an increase in 30-day wound-related morbidity, which was included in a statement of the World Society of Emergency Surgery in emergency repair of complicated abdominal hernia.3 Previous studies have reported no difference in mesh infection using synthetic or biological mesh. Furthermore, more recurrences had been reported while using primary repairs or biological meshes than while using synthetic ones.10

Eid et al12 reported zero recurrence rates at 13-month follow-up synthetics meshes concomitantly with RYGB. Similarly, while we are reporting a small group of patients, after one year of follow-up, nobody presented any recurrences or mesh infections. Another controversy is the expected necessary prolonged operating time in a high risk patient to perform both procedures at the same time, but in the hands of an experienced surgeon, the time could be drastically reduced. We consider that both procedures do not necessarily have to be performed by the same surgeon. When bariatric surgeons have a good experience doing VHR, it can be done by themselves, but if not, a hernia specialist can help perform the hernia repair, reducing the time and improving the results. In our experience, the order of the steps during the performance of the surgery can help increase the safety and reduce the operating time. We recommend starting with the lysis of adhesions and reduction of the hernia sac contents, because it allows the surgeon to perform the bariatric surgery safely. The second step is the bariatric procedure itself, and at the end, the performance of the hernia repair and mesh placement.

Obesity is a risk factor for recurrence after VHR.12 Bariatric surgery reduces this risk by treating obesity. In his institution, P. Praveen Raj routinely combines bariatric surgery with laparoscopic IPOM without additional complications.14,15 He describes a technique similar to that used by our surgical team: the first step is adhesiolysis and reduction of the contents of the hernial sac. The second step is to perform the bariatric procedure, and the third step is the hernia repair.16 Eid et al12 said in his case series study: “Repair of ventral hernias in morbidly obese patients undergoing laparoscopic gastric bypass should not be deferred.” The repair of the ventral hernia with either the primary repair method or the synthetic mesh method is performed during the final stages of the bariatric surgery,12 which supports our surgical technique.

We consider that it is most important to repair the smaller hernia defects at the same time as bariatric surgery; defects smaller than 5cm have more risk to incarceration, and for this reason, it is highly recommended to repair it at the same time that bariatric surgery is performed. This is especially important if it is mandatory to reduce the omentum from the hernia sac to perform the bariatric surgery because those hernias have major risks of complications. High rates of small bowel obstruction from incarceration have been reported when the hernia was left in place—or in cases when only primary sutures were used—so we concluded that deferral of definitive repair should be avoided in patients with small hernia defects.11 For this reason, we prefer to avoid leaving the hernia in place for a second stage, considering that deferring repair of the defect carries a significant risk of small bowel incarceration, leading obstruction or even perforation that could end up as a disaster.11–17

Eid et al12 retrospectively analyzed a cohort of 85 patients with a ventral hernia who underwent laparoscopic RYGB, reporting no significant difference between groups for postoperative length of stay in repair with sutures and mesh repair; however, he reported a recurrence rate of up to 22 percent when the suture was used for hernia repair compared to no recurrences when using a synthetic mesh. Another condition that needs to be considered is the coverage of bariatric surgery and VHR for insurance companies. In several countries, the bariatric procedures are not accepted for payers but hernias have coverage. Sometimes, it is the only opportunity for patients with morbid obesity and ventral hernia to get easy access to bariatric surgery because hospitals can reduce the cost of both procedures at the same time. We had three patients who said that was the reason they receieved both procedures at the same time. These patients also had the largest hernia defects.

We consider it is important to report our data, because even though it is a small number of patients, all of them had at least one year follow-up with good results. It is difficult to obtain good evidence on this topic because only a small number of patients present with these complex issues (some of them are preoperatively misdiagnosed), so adequate power cannot be established and valid statistical analysis is almost impossible. In addition, blind randomizations would be virtually impossible given the wide variation in the types and size of hernias and the difference in BMI and comorbidities of each patient.

Conclusion

The repair of ventral hernia with synthetic mesh concomitantly to bariatric surgery is feasible, and it offers safety in term of infections. The risk of hernia incarceration and small bowel obstruction after leaving an unrepaired small hernia defect during a bariatric procedure is high and could be questionable. Larger series and prospective collected data are necessary for stronger evidence and to determinate the long-term recurrence rates.

References

- Sugerman HJ, Kellum Jr JM, Reines HD, et al. Greater risk of incisional hernia with morbidly obese than steroid-dependent patients and low recurrence with prefascial polypropylene mesh. Am J Surg. 1996;171(1):80–84.

- Lazzati A, Bou Nassif G, Paolino L. Concomitant ventral hernia repair and bariatric surgery: a systematic review. Obes Surg. 2018;28(9):2949–2955.

- Ching SS, Sarela AI, McMahon MJ, et al. Comparison of early outcomes for laparoscopic ventral hernia repair between nonobese and morbidly obese patient populations. Surg Endosc. 2008;22(10):2244–2250.

- Liang MK, Holihan JL, Itani K, et al. Ventral hernia management: expert consensus guided by systematic review. Ann Surg. 2017;265(1):80–89.

- Regner JL, Mrdutt MM, Munoz-Maldonado Y. Tailoring surgical approach for elective ventral hernia repair based on obesity and National Surgical Quality Improvement Program outcomes. Am J Surg. 2015;210(6):1024–1029; discussion 1029–1030.

- Lo Menzo E, Hinojosa M, Carbonell A, et al. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery and American Hernia Society consensus guideline on bariatric surgery and hernia surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018;14(9):1221–1232.

- Lau B, Kim H, Haigh PI, Tejirian T. Obesity increased the odds of acquiring and incarcerating noninguinal abdominal wall hernias. Am Surg. 201278(10):1118–1121.

- Lee L, Mata J, Landry T, et al. A systematic review of synthetic and biologic materials for abdominal wall reinforcement in concomitanted fields. Surg Endosc. 2014;28(9):2531–2546.

- Birindelli A, Sartelli M, Saverio D, et al. 2017 update of the WSES guidelines for emergency repair of complicated abdominal wall hernias. World J Emerg Surg. 2017;12:37. eCollection 2017.

- Datta T, Eid G, Nahmias N, Dallal RM. Management of ventral hernias during laparoscopic gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008;4(6):754–757.

- Cozacov Y, Szomstein S, Safdie FM, et al. Is the use of prosthetic mesh recommended in severely obese patients undergoing concomitant abdominal wall hernia repair and sleeve gastrectomy? J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218(3):358–362.

- Eid GM, Mattar SG, Hamad G, et al. Repair of ventral hernias in morbidly obese patients undergoing laparoscopic gastric bypass should not be deferred. Surg Endosc. 2004;18(2):207–210.

- Sauerland S, Korenkov M, Kleinen T, et al. Obesity is a risk factor for recurrence after incisional hernia repair. Hernia. 2004;8(1):42–46.

- Praveen Raj P, Senthilnathan P, Kumaravel R, et al. Concomitant laparoscopic ventral hernia mesh repair and bariatric surgery: a retrospective study from a tertiary care center. Obes Surg. 2012;22(5):685–689.

- Praveen Raj P, Gomes RM, Kumar S, et al. Concomitant bariatric surgery with laparoscopic intra-peritoneal onlay mesh repair for recurrent ventral hernias in morbidly obese patients: an evolving standard of care. Obes Surg. 2016;26(6):1191–1194.

- Praveen Raj P, Bhattacharya S, Kumar S, et al. Concomitant intraperitoneal onlay mesh repair with endoscopic component separation and sleeve gastrectomy. J Minim Access Surg. 2018;14(3):256–258.

- Eid GM, Wikiel KJ, Entabi F, et al. Ventral hernias in morbidly obese patients: a suggested algorithm for operative repair. Obes Surg. 2013;23(5):703–709.

Category: Case Report, Past Articles