Raising the Standard: Effect of Bias on Clinical Outcomes

by Dimitra Lotakis, MD, and Dominick Gadaleta, MD, FACS, FASMBS

by Dimitra Lotakis, MD, and Dominick Gadaleta, MD, FACS, FASMBS

Dr. Lotakis is a General Surgery Resident at NYMC Metropolitan Hospital in New York, New York. Dr. Gadaleta is Chair, Department of Surgery, Southside Hospital; Director, Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery, North Shore University Hospital, Northwell Health, Manhasset, New York; Associate Professor of Surgery, Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell, Hempstead, New York.

FUNDING: No funding was provided for this article.

DISCLOSURES: The authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Bariatric Times. 2020;17(5):16–17

“Knowing yourself is the beginning of all wisdom.”

–Aristotle

As healthcare providers, our success is largely determined by a strong knowledge base and skilled pattern recognition. This foundation allows for detail-oriented evaluation, workup, and management. We must, however, thoroughly understand the external and, perhaps more importantly, internal pressures that exert force on this foundation. Financial, time-based, and physical constraints are examples of easily identified external pressures that have potential to alter or limit our relationships to patients. As one can imagine, external forces are generally easier to identify, and as a result, mitigating these risks is often simpler. But what about the internal pressures at play? Emotional stress, fatigue, and our own personal history are all major contributors that affect our approach to each patient. These forces result in the development of heuristics, which often go unnoticed and unnamed. It is these inherent cognitive biases that leave our patients at risk and lead to both medical error and dissatisfaction in care.1 Over 50 types of bias have been defined,2 many of which are centered around a provider’s relationship to clinical information and statistical data. Another subset of these biases, however, are driven by an individual’s personality and personal history.

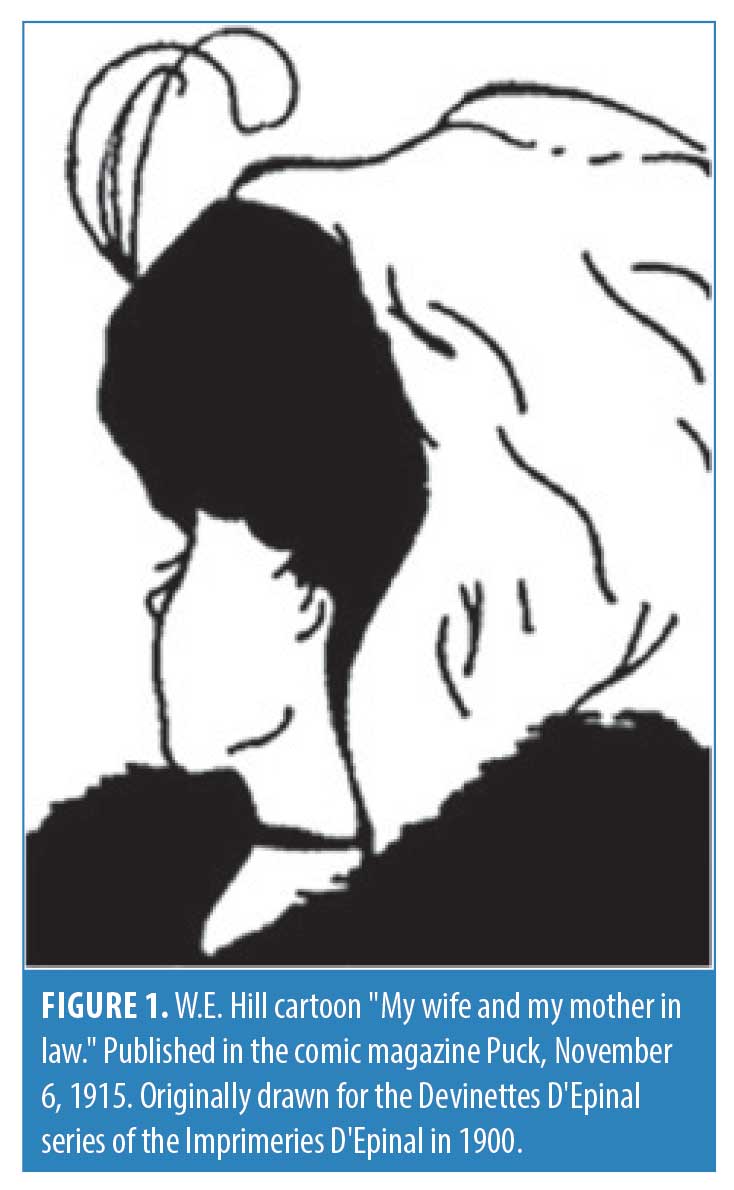

If we examine the image represented in Figure 1, many will first identify a young lady while others will mark the presence of an old woman. A quantitative analysis of this occurrence was performed by Nicholls et al,3 which demonstrated statistically significant age-related bias in reporting which image was first seen in this popular optical illusion.3 If we apply this to our relationships with patients, it becomes abundantly clear that socioeconomic, political, and religious backgrounds play a significant role in an individual’s cognitive bias. It is this phenomenon that each healthcare provider must explore and understand to achieve excellence in care.

Belief bias is clearly defined as the tendency to accept or reject data depending on a personal belief system.2 Fortunately, we have methods with which to combat this bias—by developing skills of logic reasoning and argumentation, our susceptibility fades. Another important consideration is Ascertainment bias,2 which describes when a provider’s thought processes are influenced by prior expectations, such as gender bias. If we then consider fundamental attribution error, it becomes clearer how preformed stereotypes prejudice our perceptions. This form of bias elucidates the propensity to criticize and place responsibility on patients for their maladies instead of assessing the entire clinical picture. Specific patient populations are at particular risk with regard to attribution error, including minorities and those whom carry psychiatric diagnoses.4

Unfortunately, these types of heuristics contribute to potential error because they directly influence the principle of unpacking.2 Due to preformed notions regarding stereotyped patients, many providers might fail to obtain all the salient information during the initial history and physical resulting in missed or incorrect diagnoses. Leading questions with narrowed focus produce limited history and restricted differentials. In this regard, much has been published regarding the biased treatment of patients with obesity. Bertakis and Azari’s 2005 publication is widely cited in the literature, which elucidated that physicians spent significantly less time discussing current issues and overall health maintenance with patients with obesity, instead focusing on primarily on exercise for the duration of the visit.5

It is important to reflect on a provider’s own self-image in relation to heuristics. Regrettably, healthcare providers are susceptible to blind spot, ego and overconfidence bias.2 This is a lethal triad that describe the belief that we are less susceptible to bias, a false confidence that our patient’s prognosis is better than that of the general population, and our overall propensity to think we know more than we actually do. These tendencies result in inaccurate assessments and negatively impact the care of patients. When considering this principle, it is important to reflect on the potential negative effects on the patient–provider relationship and shared decision making.4

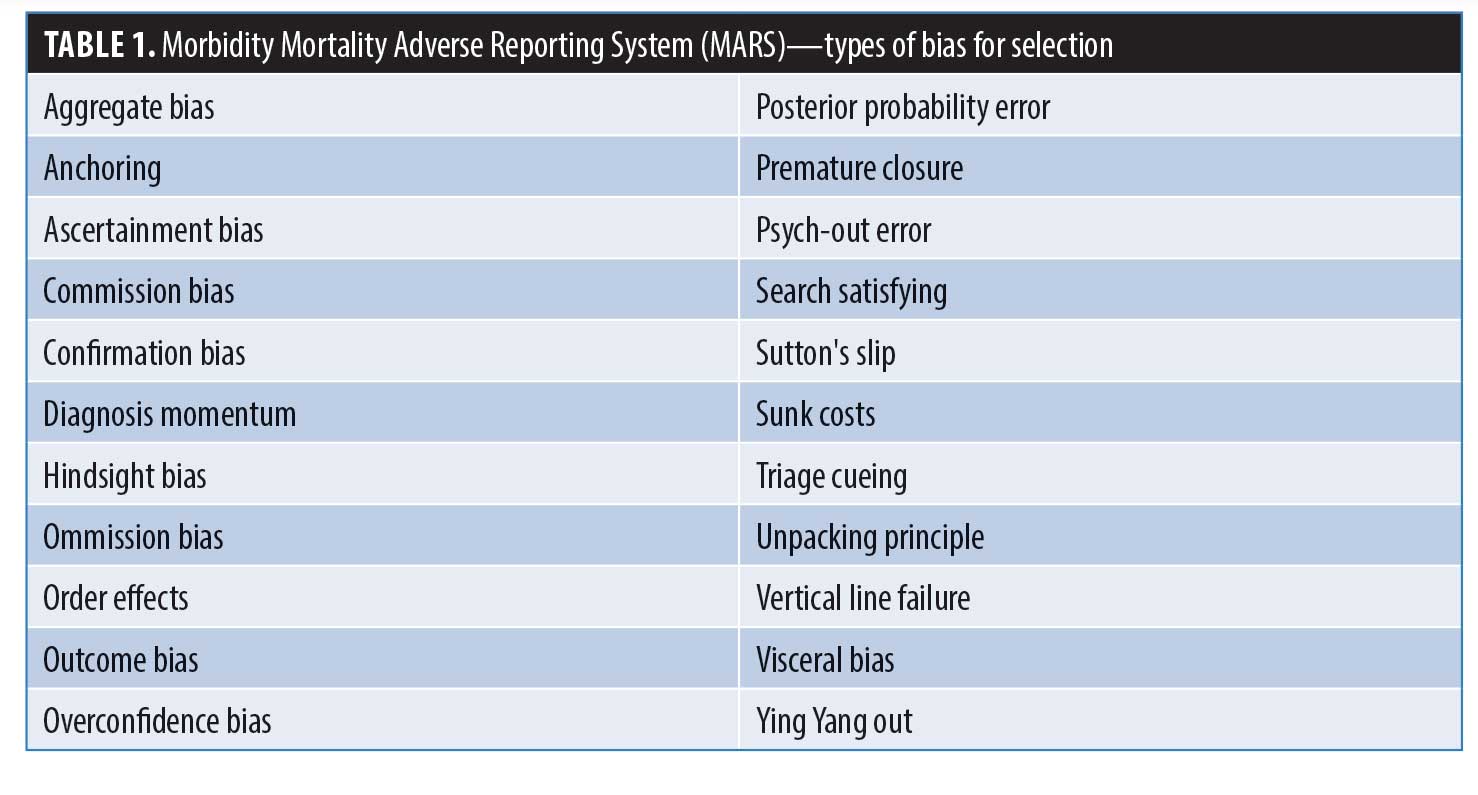

Medical school curricula focus on educating future providers on bias in relation to scientific publication and its effects on data-driven conclusions. Little guidance is provided with respect to cognitive bias in clinical practice as discussed. Mamede et al6 provide compelling evidence to show educational intervention surrounding the presence of bias and its effects on clinical care results in meaningful improvement in care.6 This indicates that the most important intervention we can implement as a medical community is to include presence of bias in the conversation when discussing the barriers to providing high quality care.7 Our goal is to improve and refine the education of residents with respect to bias in medicine and its relation to errors. By utilizing the Morbidity Mortality Adverse Reporting System (MARS) we have worked to increase each resident’s awareness and understanding of a wide range of biases.8 At the beginning of each academic year a training session is conducted for all residents to ensure understanding of both the technical software as well as each type of bias represented in the system (Table 1). Subsequently throughout the year, each morbidity and mortality suffered is subject to analysis and entered into a secured Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) compliant portal. The reporting resident then performs a case critique, comprised of a detailed evaluation of causality, including delineation of any involved types of bias and any clinical factors contributing to the error. This system has proven to be an efficient and efficacious teaching tool to increase provider awareness surrounding bias and its effect on patient outcomes.

Unconscious bias exerted by providers is a major contributor to healthcare disparities and deficiencies seen within our current system. Arming providers with knowledge and strategies to combat these negative forces is a durable solution for stimulating change. However, to accomplish this, a paradigm shift must first occur in which bias becomes a part of meaningful conversation and prominent focus rather than simply a fleeting idea.

Unconscious bias exerted by providers is a major contributor to healthcare disparities and deficiencies seen within our current system. Arming providers with knowledge and strategies to combat these negative forces is a durable solution for stimulating change. However, to accomplish this, a paradigm shift must first occur in which bias becomes a part of meaningful conversation and prominent focus rather than simply a fleeting idea.

References

- Saposnik G, Redelmeier D, Ruff CC, et al. Cognitive biases associated with medical decisions: a systematic review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2016;16:138.

- Croskerry P. (November 2011). 50 Cognitive and Affective Biases in Medicine. Oxford Medicine Online Library. www.oxfordmedicine.com. http://sjrhem.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/CriticaThinking-Listof50-biases.pdf. Accessed March 3, 2020.

- Nicholls MER, Churches O, Loetscher T. Perception of an ambiguous figure is affected by own-age social biases. Sci Rep. 2018;8:12661.

- Peek ME, Odoms-Young A, Quinn MT, et al. Race and shared decision-making: perspectives of African-Americans with diabetes. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(1):1–9.

- Bertakis K, Azari R. The impact of obesity on primary care visits. Obes Res. 2005;13(9):1615–1623.

- Mamede S, van Gog T, van den Berge K, et al. Effect of availability bias and reflective reasoning on diagnostic accuracy among internal medicine residents. JAMA. 2010;304(11):1198–1203.

- Santry H, Wren S. The role of unconcious bias in surgical safety and outcomes. Surg Clin North Am. 2012; 92(1):137–151.

- Genser K, Antonacci A, Nicastro JM, Coppa GF. Resident and attending impressions of a novel electronic tool for the recording of surgical morbidity and mortality case data: the preparation of case presentations and resident evaluation. J Am Coll Surg. 2017;225(4, Suppl 2):e158–159.

Category: Past Articles, Raising the Standard