Exploring Outcomes After Bariatric Surgery in Patients with Heart Failure

by Tiffany Nevill, DO; Devan Lenhart, DO; Samantha Maurer, MS; Joshua Parreco, MD, FACS; and Kandace Kichler, MD, FACS

Drs. Nevill and Lenhart are with the Department of General Surgery, Franciscan Health Olympia Fields in Olympia Fields, Illinois, and the College of Osteopathic Medicine, Midwestern University in Downers Grove, Illinois. Ms. Maurer is with the College of Osteopathic Medicine, Midwestern University in Downers Grove, Illinois. Dr. Parreco is with the Department of Trauma and Critical Care, Memorial Regional Hospital in Hollywood, Florida. Dr. Kichler is with the Department of Bariatric Surgery, JFK Medical Center in Atlantis, Florida, and the Department of Surgery, University of Miami in Miami, Florida.

Funding: No funding was provided for this article.

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Bariatric Times. 2022;19(5):12–13.

Abstract

Patients undergoing bariatric surgery often have medical comorbidities that contribute to morbidity, mortality, and risk of readmission. We sought to evaluate the correlation between heart failure (HF) and mortality rate during index admission, as well as the risk of readmission within 30 days of primary bariatric surgery. We also sought to identify gaps in the current guidelines and research for patients with HF undergoing bariatric surgery.

Methods: The Nationwide Readmissions Database for 2010 to 2014 was queried for patients undergoing laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy or Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. The primary outcome was mortality during the index admission. The secondary outcomes were readmission within 30 days and readmission to a different hospital. Univariable comparison was made using chi-square tests, and multivariable logistic regression was done for each statistically significant outcome.

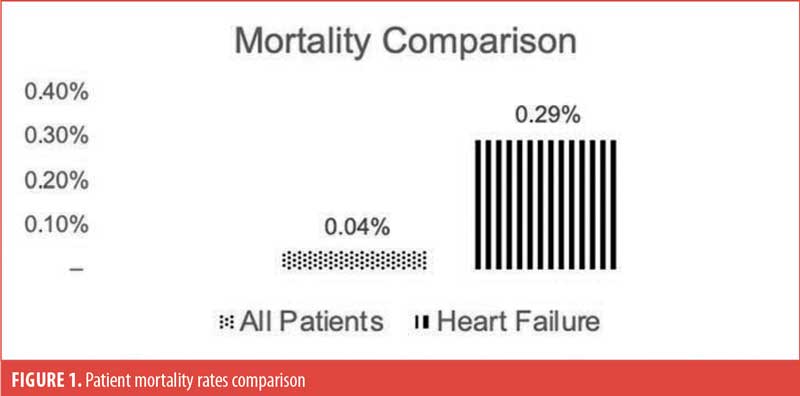

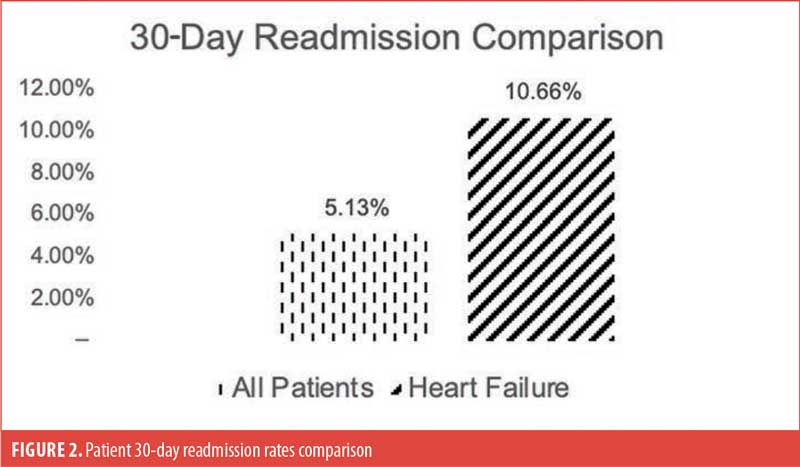

Results: From 2010 to 2014, 915,792 patients underwent bariatric surgery in the United States. Of these, 15,011 had HF during the index admission. The overall mortality rate was 0.04 percent, and the mortality rate for patients with HF was 0.29 percent (p<0.001). After controlling for confounding factors, the risk of mortality during the index admission for patients with HF was not statistically significant (p=0.439). The overall 30-day readmission rate was 5.13 percent, and it was 10.66 percent for patients with HF, revealing an increased risk of readmission for these patients (p<0.001). There was no difference in risk for readmission to a different hospital (p=0.335).

Conclusion: There is no increased risk of mortality during the index admission for patients with HF undergoing bariatric surgery. The 30-day readmission rate is significantly higher when compared to patients without HF. Currently, there is limited research for any specific guidelines on patients with HF undergoing bariatric surgery to ensure perioperative and postoperative risk reduction.

Keywords: Heart failure, bariatric surgery, obesity, metabolic surgery, readmission, mortality, surgical outcomes, quality measures

Obesity rates are growing at an exponential rate worldwide, and obesity continues to be one of the largest health epidemics to date. From 1975 to 2016, obesity prevalence tripled, and it is estimated that approximately 39 percent of the adult population aged 18 years and older are overweight, and 13 percent have obesity.1 The most effective treatment option for morbid obesity is bariatric surgery because of the sustained weight loss and positive effects on comorbidities. Throughout the last two decades, there has been an increasing number of bariatric procedures worldwide.2,3 Obesity affects numerous aspects of physical and emotional health, so patients who undergo bariatric surgery often have significant medical conditions associated with obesity, such as heart failure (HF), hypertension (HTN), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and diabetes.4 These medical comorbidities can contribute to morbidity and mortality rates during the index admission, which is the initial admission at the time of surgery, and the risk of readmission within 30 days. Outcomes are important for evaluating patient safety and areas for quality improvement. HF is of particular interest, given its strong predictive value of perioperative morbidity and mortality.5

To assess outcomes and correlation between HF and mortality rate, it is also important to understand the current recommendations for preoperative, perioperative, and postoperative care in bariatric surgery. A better understanding of postoperative care provides an opportunity to identify areas of strength and areas of quality improvement to minimize readmission rates. The World Journal of Surgery outlined recommendations for perioperative care in bariatric surgery after analyzing studies from 1966 to 2015 on bariatric surgical procedures performed worldwide. Several of the postoperative recommendations made include postoperative analgesia, oxygen, and non-invasive positive pressure ventilation. These recommendations were initially extrapolated from nonbariatric settings because there was previously no consensus regarding optimal care in bariatric surgery.2

The American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) outlined guidelines for reporting bariatric surgeries in 2015 after noting that there were no standardized outcome reporting standards. The recommendations included how to communicate follow-up care, weight loss, and management of diabetes, HTN, obstructive sleep apnea, and dyslipidemia in patients undergoing bariatric surgery. Even with these gaps addressed, there continues to be a lack of information on patients with HF undergoing bariatric surgery.6

Because HF is a known common comorbidity of patients undergoing bariatric surgery, and its direct association with perioperative and postoperative morbidity, mortality, and risk of readmission are well-known, we sought to evaluate the correlation between HF and mortality rate during index admission, as well as the risk of readmission within 30 days of primary bariatric surgery. Secondarily, we identified gaps in the current guidelines and research for patients with HF undergoing bariatric surgery.

Methods

The Nationwide Readmissions Database for 2010 to 2014 was queried for all patients undergoing laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy or Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Patients who received a gastric banding procedure, duodenal switch, or any other type of bariatric surgery were not included in the study. From 2010 to 2014, there were 915,792 patients undergoing bariatric surgery in the United States (US), of which 15,011 had a history of HF. The primary outcome was mortality during the index admission. Secondary outcomes included readmission within 30 days and readmission to a different hospital. Univariable comparison was made using chi-square tests, and the statistically significant variables were then used with multivariable logistic regression for each outcome.

Results

There were 915,792 patients undergoing bariatric surgery in the US during the study period. Of these patients, 15,011 had HF during the index admission. Table 1 shows the overall mortality rate was 0.04 percent (n=368), while the mortality rate for patients with HF was 0.29 percent (n=44, p<0.001; Figure 1). After controlling for confounding factors through multivariable logistic regression, the risk of mortality during the index admission for patients with HF was not statistically significant (Odds ratio [OR]: 1.16, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.80–1.69, p=0.439). Table 1 also shows that the overall 30-day readmission rate was 5.13 percent (n=46,936); for patients with HF, the rate was 10.66 percent (n=1,596; Figure 2). The regression revealed an increased risk of readmission for these patients (OR: 1.51, 95% CI: 1.43–1.60, p<0.001). However, there was no difference in risk for readmission to a different hospital (OR: 1.07, 95% CI: 0.94–1.21, p=0.335).

Discussion

Surgical outcomes are increasingly important in today’s healthcare system, as individual physicians and hospitals are measured using different quality metrics. Unfortunately, readmission rates are very directly tied to hospital reimbursements, causing this to be a quality measure that surgeons must monitor in their practices.7 There are multiple quality metrics utilized to measure surgical outcomes, and unfortunately, there is no specific consensus on what quality metrics perfectly define adequate outcomes.8 Thus, identifying areas, such as mortality and readmission rates (which are clearly measurable metrics), that can be improved will positively impact patient care and surgical outcomes.

It has previously been shown that bariatric surgery can be used as primary prevention for the development of HF. A cohort study of 47,859 patients with obesity showed that HF incidence was five times less in patients who underwent bariatric surgery than those who did not. This was consistent in all age groups and in patients with coronary artery disease, HTN, and diabetes.9 Another cohort study of 3,448 patients with obesity showed that after eight years, patients who underwent surgery had a decreased incidence of HF and lower risk of death from HF.10 However, patients that have previously developed HF are likely sicker than those without, and they are in greater need of HF research to improve their disease and quality of life. Our study did not prospectively quantify the risk of mortality in patients with HF with and without bariatric surgery, but it showed that, in the short-term, patients with HF are not at a significantly higher risk of death from bariatric surgery, compared to patients without HF. This could suggest that, after appropriate cardiac optimization, bariatric surgeons can feel confident that their patients with HF will not be at an increased risk of perioperative mortality when compared to those without HF.11

Although there was not a statistically significant increase in perioperative mortality for patients with HF, our study showed that within the first 30 days after surgery, patients with HF had a significantly higher rate of readmission, compared to patients without HF. Of note, rates of readmission were not significantly increased at outside hospitals within the 30 day period. It is suspected that the rate of readmission at outside hospitals was not increased because bariatric surgery patients are advised to follow up with their surgeon and care team.12 The rate of readmission might have occurred because patients with HF have more chronic diseases and are more likely to be hospitalized, regardless of surgery.13 In addition, not all benefits of bariatric surgery occur immediately, as weight loss occurs over months to years.14

One study that looked at the benefits of a multidisciplinary pathway for surgical care for cardiac optimization in complex patients demonstrated that with teams composed of members from the fields of bariatric surgery, advanced heart failure/transplant cardiology, hematology, anticoagulation pharmacy, and cardiac anesthesia, bariatric surgeries can be successful for patients with HF. Postoperatively, this study emphasized beneficial patient management strategies, such as admission into cardiac intensive care unit; medication titration while in the hospital; and discharge criteria, including 24 hours of no changes in cardiac medications and adequate oral intake. Additionally, the follow-up explained in this study involved patients seeing an advanced heart failure team within seven days of discharge for medication adjustment, then again within two weeks for general assessment and diet advancement. In this sample size of five patients, there was one readmission.15 Although this study demonstrates a good start to research specifically analyzing bariatric management for patients with HF, the sample size was small, and there is limited additional research on steps to specifically prevent readmission.

One barrier to creating postoperative bariatric guidelines for patients with HF lies in the fact that overall, for any type of bariatric patient, there has not been a uniform method or even a requirement to report follow-up rates and outcomes.6 Even more specifically, there is limited research on the cardiologist’s role throughout a bariatric surgery patient’s hospital stay. Outcomes could potentially change with increased follow-ups or having the patient’s cardiologist act as a postoperative inpatient consultant, as discussed in the study from Kindel.15 Additionally, there is limited research on length of stay for patients with HF undergoing bariatric surgery. Further examination of length of stays and the correlation to readmissions could better identify specific areas for optimization in the early postoperative course, which is so pivotal for recovery. Our data set did not include length of stay, so this was an area identified that could be assessed in the future. A specific recommendation made by the ASMBS involved a systematic way of reporting complications. This recommended practice involved reporting complications based on time frame, less than 30 days and more than 30 days, or based on complications, major and minor.6 More investigations identifying types of complications and the timeline of those complications could help pinpoint the root cause of elevated readmission rates in bariatric patients with HF.

Our data and preliminary findings, as outlined above, can benefit the field of bariatric surgery in a few ways. First, the mortality rate demonstrates that bariatric surgeons should not shy away from operating on patients with HF. Second, bariatric centers should begin to evaluate their readmission rates and consider areas in their practice to optimize preoperative, perioperative, and postoperative care to ensure an enhanced recovery and decreased readmission rate for patients with HF. This is a tangible way to improve surgeon and hospital outcomes and quality measures. Third, the holes in our own data provide a framework for future research and quality improvement projects.

Limitations

These results must be read with the understanding that the study presents some limitations. First, the research data that was utilized was from the Nationwide Readmission Database from 2010 to 2014, which is a limited and slightly removed time frame. Additionally, the data fails to specify exact reasons for readmissions. While any postoperative readmission negatively impacts quality measures,7 the reason for readmission could possibly be unrelated to HF and the postsurgical state, such as trauma or unrelated illness. Our data does not extend beyond 30 days, and readmission risks from 30 to 90 days would also be valuable to assess for surgeon outcomes. Another limitation is that the deidentified data bank that was used did not have any further information on severity, etiology, or onset of HF. To best characterize the influence of HF on readmissions, these factors would need to be considered. Finally, this study only looked at patients who specifically received laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy or Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and excluded all other bariatric procedures. Even comparing sleeve gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass could potentially be a weakness to the data, as the two procedures have differences in operative time and intraoperative blood loss. All these limitations are areas for future improvement, as well as possible areas of weakness in our data and subsequent conclusions.

Conclusion

There is no increased risk of mortality during the index admission for patients with HF undergoing bariatric surgery. Although having HF did not statistically affect the mortality of patients undergoing bariatric surgery during the index admission, the readmission rate was significantly higher when compared to patients without HF.

By exploring these outcomes, future quality improvement projects could address solutions to reduce readmission rates in this specific population of patients with HF who undergo either laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy or Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Future research should target preoperative medical optimization, slightly longer index admission stays, medication titration, postoperative cardiologist management in the hospital, or closer follow-up appointments, all with the goal of readmission risk reduction, which theoretically would improve patient-reported outcomes as well. These are all areas of limited research in assessing patients with HF undergoing bariatric surgery. Longer index admission stays would need to include a risk analysis for potential infection associated with longer hospital stay.

Additionally, the same statistical analyses could be completed with data queried from patients between 2014 to the present. With this comparison and identification of protocol changes, there is potential to identify variables that have improved care already, as well as to establish further patient care advancements in this specific patient population that will positively impact surgical outcomes and quality measures.

References

- World Obesity Federation. Obesity and overweight. World Health Organization. 9 Jun 2021. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight. Accessed 12 Jan 2022.

- Thorell A, MacCormick AD, Awad S, et al. Guidelines for perioperative care in bariatric surgery: enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) society recommendations. World J Surg. 2016;40(9):2065–2083.

- Blumer V, Greene SJ, Ortiz M, et al. In-hospital outcomes after bariatric surgery in patients with heart failure. Am Heart J. 2020;230:

59–62. - Kenchaiah S, Evans JC, Levy D, et al. Obesity and the risk of heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(5):305–313.

- Barie PS. Perioperative management. In: Norton, JA (ed). Surgery: Basic Science and Clinical Evidence, Second Edition. New York, New York: Springer Science; 2008:323–351.

- Brethauer S, Kim J, Chaar M, et al. Standardized outcomes reporting in metabolic and bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2015;11(3):

489–506 - Berenson RA, Paulus RA, Kalman, NS. Medicare’s readmissions-reduction program—a positive alternative. N Engl J Med 2012;366(15):1364–1366

- Ibrahim AM, Dimick JB. What metrics accurately reflect surgical quality? Annu Rev Med. 2018;69:481–491.

- Persson CE, Björck L, Lagergren J, et al. Risk of heart failure in obese patients with and without bariatric surgery in sweden—a registry-based study. J Card Fail. 2017;23(7):530–537.

- Benotti PN, Wood GC, Carey DJ, et al. Gastric bypass surgery produces a durable reduction in cardiovascular disease risk factors and reduces the long‐term risks of congestive heart failure. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(5):e005126.

- Vest AR, Schauer PR, Young JB. Failure and fatness. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(8):904–906.

- Thereaux J, Lesuffleur T, Païta M, et al. Long-term follow-up after bariatric surgery in a national cohort. Br J Surg. 2017;104(10):

1362–1371. - Shimada YJ, Tsugawa Y, Brown DFM, Hasegawa K. Bariatric surgery and emergency department visits and hospitalizations for heart failure exacerbation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(8):895–903.

- Kuno T, Tanimoto E, Morita S, Shimada YJ. Effects of bariatric surgery on cardiovascular disease: a concise update of recent advances. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2019;6:94.

- Kindel TL, Higgins RM, Lak K, et al. Bariatric surgery in patients with advanced heart failure: a proposed multi-disciplinary pathway for surgical care in medically complex patients. Surgery. 2021;170(3):659–663.

Category: Past Articles, Review