Can The “Collective Impact” Framework Model Lower Obesity Rates and Healthcare Costs Around The World?

by Maher El Chaar, MD

Dr. El Chaar is with St. Luke’s University Hospital and Health Network in Allentown, Pennsylvania.

Funding: No funding was provided for this article.

Disclosures: Dr. El Chaar is a speaker and consultant for Intuitive surgical, WL Gore, and Boehringer and serves on the advisory board of FruitStreet and SurgeOn.

Bariatric Times. 2023;20(7–12):12–14.

Abstract

Obesity and obesity related health conditions are major health issues mostly driven by nonclinical social determinants of health and result in poor outcomes and increased healthcare costs. To address the obesity crisis, in addition to providing individual healthcare, we need to address the obesity-related health needs (ORHN) using evidence based innovative frameworks. Despite the availability of resources our healthcare system is a fragmented system and the only way to win the fight against obesity is to align our activities and leverage our resources toward a common goal and the collective impact (CI) model is a validated framework that can be used to achieve that goal.

Keywords: Obesity-related health needs, collective impact, morbid obesity, healthcare costs

Obesity is a major healthcare problem in the United States (US) and other countries across the globe. Obesity rates have reached pandemic proportions and resulted in increased healthcare costs. Obesity-related health conditions, such as hypertension, sleep apnea, Type 2 diabetes, and many others also result in additional healthcare expenditures. It is estimated that in the US alone, almost $900 billion, or a total of 16 to 18 percent of healthcare expenditures, will be attributed to obesity and obesity-related health conditions by 2030.1 Due to increased healthcare costs and poor patient outcomes, in 2008 the Institute of Healthcare Improvement (IHI) developed the triple aim, which requires the pursuit of three goals: improving individual healthcare, improving population health, and reducing costs.2 The triple aim later became part of the national strategy for tackling the healthcare crisis, especially with the implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA). In a previous publication,3 we argued that to address the increasing obesity rates and improve the health outcomes of patients suffering from obesity, the upstream causes of obesity needed to be addressed by tackling the nonclinical social determinants of obesity, referred to as obesity-related health needs (ORHN). We also suggested the development of a hub-and-spoke model to address this deeply rooted medical and social issue to emphasize the need for collaboration among the different stakeholders.3 Obesity is a complex, “adaptive” challenge that requires a nonlinear planning model; it is not a “technical” challenge that can be addressed using a linear way of thinking, and therefore our approach to solving the obesity crisis should be innovative, creative, and follow a systemic approach instead of a programmatic approach. In the current manuscript, we discuss the “collective impact” (CI) framework developed by Kania and Kramer4 as an innovative, evidence-based model that can be utilized to lower obesity rates, improve the health individuals with obesity, and decrease healthcare costs. Previous attempts made by various institutions and professional organizations to curtail the increasing rates of obesity in the US have failed because of the reductionist approach, which assumed that the problems leading to obesity can be identified and handled separately, which is not the case, was taken. To succeed, we need to address the dynamic and complex interplay between clinical and nonclinical ORHN, using an innovative approach based on multisector collaboration, such as the CI framework. The CI model has been successfully utilized in the past to address other complex and adaptive clinical issues, such as maternal and child health.5 Given that obesity is the result of a complex interplay of clinical and nonclinical determinants, that same model can potentially be utilized to achieve the common desired objective of lowering obesity rates and healthcare costs.

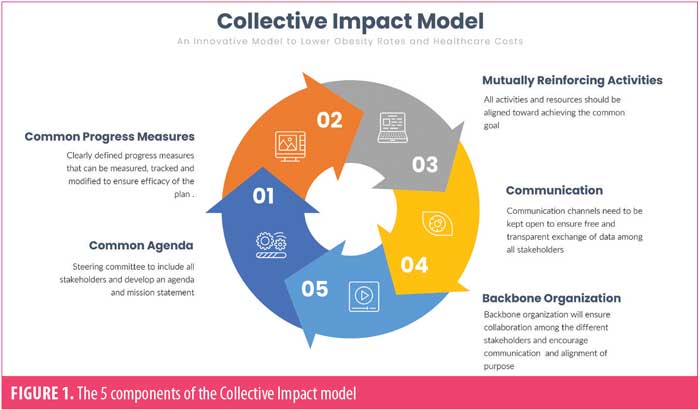

The CI framework consists of five different components and is in line with the widely recognized Community Health Improvement Project (CHIP) model that is routinely utilized to address community health issues and the Cynefin framework model that is utilized to address “adaptive” and complex challenges.6 The different components of the CI model (Figure 1) are explained below.

1. Common agenda. To implement the CI model, a steering committee needs to be created that includes all stakeholders. The stakeholders include medical professional organizations (including surgical and medical organizations), medical industry, activists, public healthcare experts, patient advocates, patients, payors, and nonclinical personnel from all agencies dealing with the upstream causes of obesity (e.g., education, transportation, US Department of Human and Health Services [HHS], National Institues of Health [NIH], Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]). The main objective of the committee is to develop a common agenda and mission statement. The committee needs to meet on a regular basis and have open discussions to reach a consensus. The issue of obesity is a complex issue, and therefore ample time should be given to the committee members to reach a consensus about the definition of the problem and agree on the mission statement and goals. Goals should be well defined and achievable. For example, one of the goals may be to reduce morbid obesity rates by 20 percent in the next 10 years or reduce overweight rates by 10 percent over the next 15 years. The committee will have to analyze available data and collect new data to develop a clear understanding of the problem before developing a mission statement and future goals. It is extremely important during that initial phase to make sure that all members continue to be engaged and agreeable to participate in the continuous process of progress measures that will be discussed next to ensure the success of the mission and the sustainability of the plan.

2. Common progress measures. Following the development of the mission statement the steering committee has to agree not only on the plan of action, but also on the common progress measures utilized to evaluate the efficacy of the plan. Progress measures can be based on factors such as obesity rates, incidence of metabolic syndrome, weight, body mass index (BMI), rates of Type 2 diabetes, mortality rates, and number of bariatric surgeries. Progress measures should be defined and agreed upon prior to the implementation of the plan. The plan should be flexible to allow changes and adjustments based on real-time feedback and outcome analysis. If, for example, morbid obesity rates were found to increase after patients were provided with meal plans or free gym memberships, the plan woud have to be changed or adjusted. Mutual accountability is also important to make sure all stakeholders continue to be engaged and leverage their resources and expertise toward the common goal. For example, if bariatric surgeons were tasked by the collaborative to provide bariatric surgery services to patients with poorly controlled Type 2 diabetes and/or morbid obesity as part of the overall 10-year plan to decrease rates of morbid obesity and Type 2 diabetes, then surgeons would have to develop a system to identify those patients and provide them with access to care. On the other hand, providing surgical services would not be enough in communities without adequate transportation, so the Department of Transportation in those communities would be held accountable for providing public transportation for those patients to ensure access to surgery.

3. Mutually reinforcing activities. The reinforcement of activities and alignment of resources are crucial for the success of any CI model. Different stakeholders need to leverage their expertise and available resources to achieve the common goal. For example, surgeons and bariatricians need to provide bariatric services and medical weight management services, while the Departments of Transportation, Labor, and Education provide better public transportation, employment opportunities, and educational services, respectively, for patients with obesity. The main issue in high-income countries with high obesity rates is not the lack of funding or availability of resources but the fragmentation of those resources and lack of accountability. Who is truly responsible for the increased rates of obesity in the US? None of the governmental health agencies would claim responsibility. All stakeholders need to be held accountable and all available resources aligned toward achieving the same goal, irrespective of the individual goals of the different agencies or stakeholders. If bariatric surgeons increase access to care and provide more bariatric services to patients with morbid obesity without achieving a decrease in the overall obesity rates, as stated in the mission statement, would that be considered a successful outcome? I would argue not. If the Department of Education or HHS provided additional educational resources for healthy eating and screening services without achieving a decrease in the overall obesity rates, as stated in the CI mission statement, would that be considered a successful outcome? I would also argue not. All of our activities need to be patient-centric and aligned toward improving patient outcomes and achieving our common agenda. Those activities can be divided into clinical and nonclinical activities:

- Clinical activities include all services provided by healthcare professionals to patients with obesity, surgical or medical. Although resources and expertise are available, those clinical activities need to be channeled into achieving a common goal, whether that goal is lowering hemoglobin A1C (HbA1c) levels, lowering BMI, decreasing stroke rates, improving functional status or activity levels of patients with obesity, or lowering mortality rates of patients with obesity.

- Nonclinical activities include all other nonmedical and nonsurgical activities related to the previously discussed social determinants, such as better education, employment opportunities, food security, neighborhood safety, and access to care.

4. Communication. Communication among the various stakeholders and between the stakeholders and community members is crucial for the success of the plan. Communication channels and methods need to be identified early on to manage conflict resolution and data sharing, as well as to ensure compliance and commitment to the process. Those channels may include a new generation of healthcare records with artificial intelligence, social media platforms, patient platforms, electronic records, and many others. Using those communication channels, data collected throughout the implementation process can be shared with the various parties and discussed openly with the community to measure progress and modify the plan to achieve the desired outcomes. Third party payors, for example, need to be informed about the progress made by surgeons on increasing access to care and outcomes in patients with Type 2 diabetes and obesity. Governmental agencies need to be continuously informed about the resources needed in communities to manage nonclinical health determinants. Communication platforms can also be utilized to engage with community members with obesity and educate them about available clinical services and locally available social services to achieve the desired outcomes based on the previously developed common agenda. For instance, patients with prediabetes and obesity cannot take advantage of online diabetes prevention programs provided by third party payors if they are not informed about the presence of such programs, provided with Wi-Fi, and educated on how those programs can be accessed.

5. Backbone organization. For the successful implementation of this initiative and to make sure the initiative efforts are sustainable, the steering committee will have to decide on a backbone organization or structure to coordinate the efforts of the various parties. The backbone organization is not meant to manage the different parties involved in the collaboration, but rather the collaboration itself. In that sense, the organization will make sure that all stakeholder activities are aligned toward achieving the common goal and fulfilling the mission. The organization will also help to ensure that communication channels remain open and all stakeholders are continuously informed about the progress being made. For example, if the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) and HHS are working together on a specific project, such as providing free HbA1C checks to patients with a BMI higher than 30kg/m2, the organization would facilitate the collaboration between the two organizations and help make sure the available resources and activities are aligned toward achieving that goal. As previously mentioned, data will be collected and analyzed throughout the plan and changes made accordingly, and the backbone organization will ensure that data is collected, analyzed, and reported to the steering committee in a timely fashion and shared with the community at large. The organization will also promote leadership development within the collaboration to ensure that leaders committed to the collaboration from all the participating organizations are identified. No specific organization is supposed to lead the collaboration, but leadership development in service of the collaboration should be encouraged among all participating stakeholders. Leaders from ASMBS, The Obesity Society (TOS), American College of Surgeons (ACS), or other professional organizations participating in the collaboration may emerge to help achieve the objectives and goals of the collaboration, but none of those organizations will lead the collaboration in the strict sense of the term. The organization may also include subcommittees to deal with the various tasks, including data collection, communication, and fundraising. Funding is also very important to make sure the effort is sustainable. Funding can be provided by local agencies, federal agencies, HHS, or even private payors interested in lowering the healthcare costs of its participating members.

In conclusion, obesity and obesity-related health conditions are major health issues largely driven by nonclinical social determinants of health and result in increased healthcare costs. To address the obesity crisis, in addition to providing individual healthcare, we need to address ORHN using nonconventional approaches that draw upon available resources. Despite the availability of resources, our healthcare system is a fragmented system, and the only way to win the fight against obesity is to align our activities and leverage our resources toward a common goal; the CI model is a validated framework that can be used to achieve that goal.

References

- Wang Y, Beydoun MA, Liang L, et al. Will all Americans become overweight or obese? Estimating the progression and cost of the US obesity epidemic. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2008;16(10):2323–2330.

- Whittington JW, Nolan K, Lewis N, Torres T. Pursuing the triple aim: the first 7 years. Milbank Q. 2015;93(2):263–300.

- El Chaar M. How can we shape our future as bariatric surgeons and win the fight against obesity in an ever-changing healthcare industry? Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2020;17(2):466–468.

- Kania J, Kramer M. Collective impact. Stanford Soc Innov Rev. 2011;9:36–41.

- Schaffer K, Cilenti D, Urlaub DM, et al. Using a collective impact framework to implement evidence-based strategies for improving maternal and child health outcomes. Health Promot Pract. 2022;23(3):482–492.

- Van Beurden EK, Kia AM, Zask A, et al. Making sense in a complex landscape: how the Cynefin Framework from Complex Adaptive Systems Theory can inform health promotion practice. Health Promot Int. 2013;28(1):73–83.

Category: Commentary, Current Issue