Raising the Standard: Conflict of Interest II: Where Do We Go Next?

by Tara McGraw, DO; Anthony Petrick, MD, FACS, FASMBS; and Dominick Gadaleta, MD, FACS, FASMBS

by Tara McGraw, DO; Anthony Petrick, MD, FACS, FASMBS; and Dominick Gadaleta, MD, FACS, FASMBS

Dr. McGraw is a PGY5 Surgical Resident at Geisinger Wyoming Valley Medical Center in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. Dr. Petrick is Chief Quality Officer, Geisinger Clinic; Director of Bariatric and Foregut Surgery, Geisinger Health System, Danville, Pennsylvania. Dr. Gadaleta is Chair, Department of Surgery, South Shore University Hospital; Director, Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery, North Shore and South Shore University Hospitals, Northwell Health, Manhasset, New York; Associate Professor of Surgery, Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell in Hempstead, New York.

FUNDING: No funding was provided for this article.

DISCLOSURES: The authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Bariatric Times. 2021;18(7):14–15

“Whenever there is a conflict between universal principals and self-interest, self-interest is likely to prevail.”

-George Soros

Our column last month focused on conflict of interest (COI) in medicine. Readers would benefit from reading that column for perspective on this month’s column.1 The central issue raised in the June column was the discrepancy between reported COI by providers and the data reported in open payments.1 While societies and journals have attempted to update policies for speaker and author disclosures, these disclosures continue to align poorly with financial data reported in open payments, even though open payments have now been publicly available for eight years.

Protecting patients and healthcare providers from COI is the responsibility of everyone involved in the communication of medical information. This includes not only societies and journals, but also those transmitting medical information online and through social media platforms. The question of why these reporting discrepancies persist is complex. It would be convenient to assert that a lack of candor underlies the problem because of the self-interest of providers being compensated by industry. This might be the case in some of the high-profile instances cited in the June column.2 Clear guidelines, as well as sanctions for not reporting COI, would certainly help.

However, not all of the COI problem is related to “self-interest.” It can be difficult to agree on what constitutes a COI. A hypothetical example of a COI would be publication of a study in which a provider, compensated by a pharmaceutical company (beta) selling a non-opioid pain reliever (alpha), reports decreased perioperative use of opioids related to pain reliever alpha. However, such clear cause and effect is rare because causality is nearly always multifactorial. Let’s take the same example but change the outcome to length of stay (LOS) in which the author compared an enhanced recovery care pathway to historical practices. The COI would be clear if the LOS improvement was attributed to use of pain reliever alpha. However, if the LOS improvement was attributed to overall adherence to many best practice elements, including the use of pain reliever alpha, there might be some disagreement as to the “relevance” of the author’s COI attributable to compensation from pharmaceutical company beta. These associations would be easier to discern in randomized, controlled trials (RCTs), but RCTs are time-consuming, costly, and difficult to implement. Most studies are retrospective and involve many uncontrolled factors affecting outcomes, which opens the door for debate over the “relevance” of potential COIs.

COI concerns could be effectively addressed by implementing several changes to current COI reporting standards.

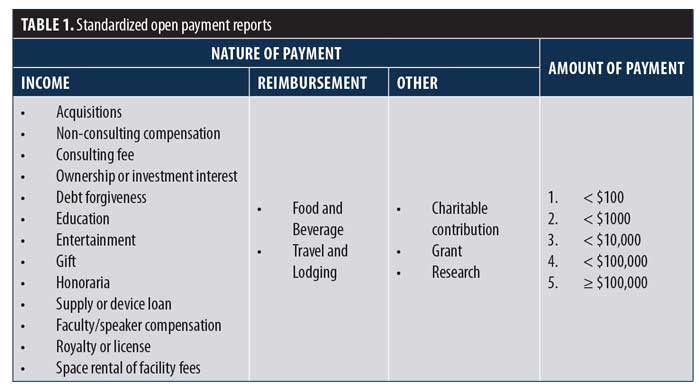

Authors should not be asked to make determinations about the relevance of their relationships with industry. We suggest that authors report the nature and amount of compensation directly from open payments. The format of reporting should be standardized with taxable income reported separately from reimbursements. The amount of payments should also be standardized. We suggest five discrete levels (Table 1). A reasonable expectation is that payment data is reported with the same accuracy as clinical data.

We can reduce the sensitivity of this topic by replacing the term “COI” with “potential COI” (pCOI). This helps make the process less judgmental and more objective. The term “potential” helps diminish the implication of bias or “self-interest” on the part of the author.

The determination of relevance of industry relationships to the content of studies should be left to reviewers, societies, and, ultimately, to readers.

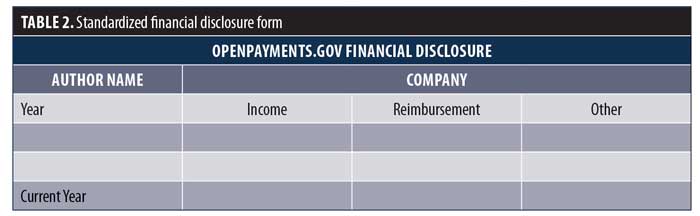

We would like to see this process standardized for both public reporting of medical studies (scientific meetings) and publication. An example of this proposal is provided in Table 2. Since open payments data is updated on June 30 each year, authors would be responsible for accurate reporting of payments not yet available at the time of disclosure.

We envision a standardized format being required of all authors for all manuscripts. Automated search software could be developed to quickly assess the accuracy of author disclosures before sending manuscripts for review. The review process would begin only after confirmation of accurate disclosures. Appropriately, pCOI data would then be available to reviewers as an added metric upon which to make a determination. Also, journal editors would have easy access to detailed reviewer pCOI, creating an opportunity to assign reviewers more suitably to manuscripts. This would enable journals to create more accurate and fair policies, addressing inaccuracy. Similar processes would be developed for the evaluation of studies for presentation at scientific meetings.

In last month’s column, we observed that, in the United States, patient interests are well protected. However, we also cited many examples that suggest there remains much room for improvement. We do not see these proposals as a final solution, but as a stimulus for a broader discussion. Eight years into public reporting of open payments, we must move beyond the current state in which the public is better informed about pCOI than many of our journals and societies.

References

- McGraw T, Petrick A, Gadaleta D. Time for medicine to catch up to the public domain in conflict of interest transparency. Bariatric Times. 2021;18(6):14–15.

- Thomas K, Ornstein C. Top Sloan Kettering cancer doctor resigns after failing to disclose industry ties. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/13/health/jose-baselga-cancer-memorial-sloan-kettering.html. Published September 13, 2018. Accessed September 15, 2018.

Category: Past Articles, Raising the Standard