Early Gastric Remnant Dilation After Conversion of Gastric Plication to RYGB: A Case Report With Video

by Enrique Arias, MD, FACS; Francisco Alexander Ruiz Zelaya, MD; Mario Nelson Urquiza Osorto, MD; Aurelio José Villalta MartÍnez, MD; and Carlos Alberto Rodríguez, MD

by Enrique Arias, MD, FACS; Francisco Alexander Ruiz Zelaya, MD; Mario Nelson Urquiza Osorto, MD; Aurelio José Villalta MartÍnez, MD; and Carlos Alberto Rodríguez, MD

Drs. Arias, Ruiz, Urquiza, Villalta, and Rodriguez are with Obesity El Salvador in San Salvador, El Salvador.

FUNDING: No funding was provided.

DISCLOSURES: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

View Video Case Report: https://vimeo.com/412738550

ABSTRACT: Background. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) is a well-known bariatric and metabolic procedure. Thus, health personnel treating patients who undergo this bariatric surgical procedure should be familiar with the potential clinical consequences of the modified anatomy induced by RYGB. Postoperatively, the stomach is left in situ after the closure of the upper part of the organ; this blind-ended gastric remnant can cause complications and surgical emergencies. Gastric greater curvature plication is a relatively new bariatric procedure that has proven to be effective in short-term reports, but revisional surgery is required in many of those procedures, usually related to inadequate weight lost or to weight regain.

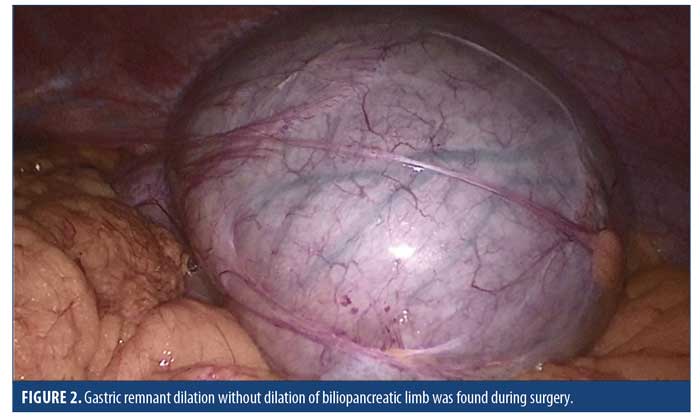

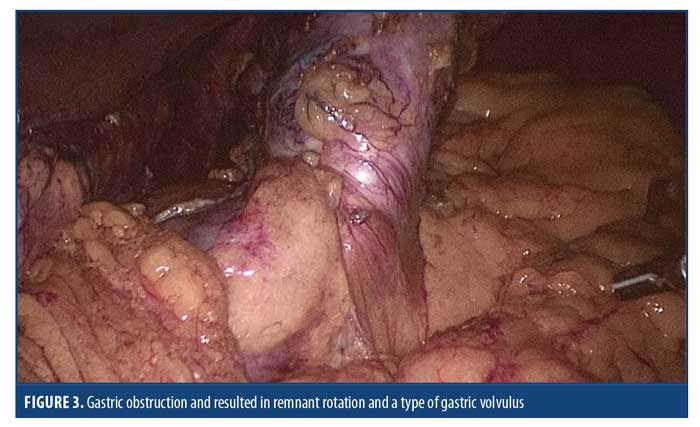

Case presentation. This case review is about a 31-year-old female patient who underwent a gastric greater curvature plication for morbid obesity treatment five years ago at another institution. Laparoscopic conversion to RYGB was performed, but she was readmitted to the hospital due to tachycardia and abdominal pain. A diagnostic laparoscopy was indicated, and during the surgery, gastric remnant dilation without dilation of biliopancreatic limb was found. An adhesion of omentum to the gastric remnant located right above the thinner part of the stomach caused the gastric obstruction; therefore, the gastric remnant was removed, including the part of obstruction. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of isolated gastric remnant dilatation after conversion of gastric greater curvature plication to RYGB.

Conclusion. Gastric remnant dilation is generally caused by biliopancreatic limb obstruction, but the surgeon must consider this diagnostic even without small bowel obstruction, especially with patients of revisional surgery. The resection of the gastric remnant could be considered, in some special cases, when performing revisional surgery from gastric greater curvature plication to RYGB.

KEYWORDS: Gastric remnant dilation, plication, volvulus

Bariatric Times. 2021;18(1):13–16

In the management of patients with morbid obesity, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) has been considered the gold standard for many years. However, RYGB is not only used as a primary procedure. In the case of unsatisfactory results after gastric banding, gastric greater curvature plication or sleeve gastrectomy (SG), RYGB is often performed as a secondary procedure.1–3 Thus, health personnel treating patients who undergo this bariatric surgical procedure should be familiar with the potential clinical consequences of the modified anatomy induced by RYGB. Postoperatively, the stomach is left in situ after the closure of the upper part of the organ. This blind-ended gastric remnant can cause complications and surgical emergencies. Gastric greater curvature plication is a relatively new bariatric procedure that has been shown to be effective in short-term reports, but revisional surgery is required in many of those procedures, mainly related to inadequate weight lost or to weight regain.2–8

Acute gastric remnant dilation, with or without biliopancreatic limb obstruction, is one of the possible complications after RYGB when performed either as a primary surgery or as a revisional procedure.1,7 It is a surgical emergency that can potentially lead to staple line disruption of the bypassed stomach with disastrous consequences. Gastric remnant dilation is generally caused by obstruction of biliopancreatic limb, and remnant dilatation without small bowel obstruction is an extremely rare situation.

Case Presentation

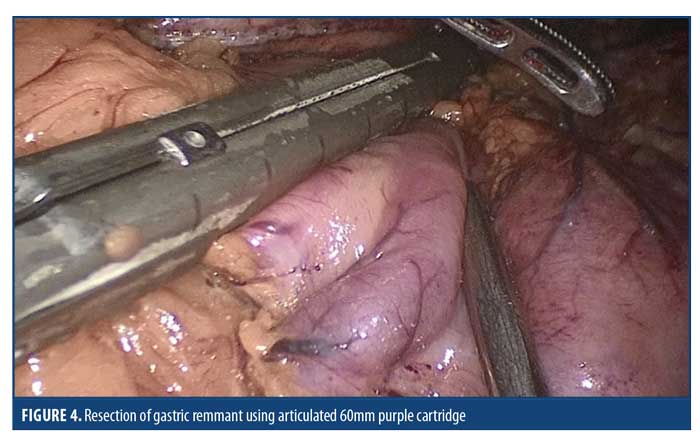

A 31-year-old female patient underwent gastric plication for morbid obesity treatment five years ago at another institution. Her initial body mass index (BMI) was 40kg/m2. During the first year, she lost 30kg and had a BMI of 28kg/m2. Eighteen months after surgery, she started to regain weight, and her final BMI was 42kg/m2. Laparoscopic conversion to a RYGB was planned; preoperative endoscopy does not show any stenosis (Figure 1). The surgery was performed uneventfully, and a 5cm length and 30mL gastric pouch was created. The gastric remnant was left in situ. We left the gastric remnant because there were no signs of ischemia and, externally, the thinner part of the gastric remnant was approximately 4cm. Mesenteric and Petersen defects were closed using nonabsorbable suture, and the patient was discharged from the hospital 48 hours after the surgery. Three days after hospital discharge, she suffered from 24 hours of abdominal pain and vomiting and was readmitted into the hospital. Plain abdominal radiography did not show any abnormality, and the endoscopy reported no obstruction in the gastrojejunostomy (GJ) junction. During her hospital stay, she presented with tachycardia and her abdominal pain persisted, so a diagnostic laparoscopy was indicated. Gastric remnant dilation without dilation of biliopancreatic limb was found during surgery (Figure 2). After decompression of gastric remnant, we identified an adhesion of omentum to the gastric remnant located right above the thinner part of the stomach, which caused the gastric obstruction and resulted in remnant rotation and a type of gastric volvulus (Figure 3). Resection of gastric remnant was performed, and the patient uneventfully recovered (Figure 4).

Discussion

As previously mentioned, gastric remnant dilation without small bowel obstruction is an extremely rare condition. While doing a literature review, we found two reported cases of dilated remnant with a normal biliopancreatic limb. The first case is an acute gastric remnant dilatation after a laparoscopic RYGB operation in a patient with long-standing Type 1 diabetes, and the second case is after one anastomosis gastric bypass (OAGB) as a primary operation.10,11 In the first case, the authors described how a systematic laparoscopic exploration revealed intact gastrojejunostomy and jejunojejunostomy anastomosis, and no evidence of an anastomotic stricture was found. She had abnormal gastric emptying, which is a frequent complication of diabetes. The authors attributed the dilated gastric remnant to gastroparesis caused by diabetes. In the second case, the authors described that the gastric obstruction was possibly caused by going too close to the greater curvature of the stomach in their pursuit of achieving the longest possible gastric pouch. In our case, the gastric pouch was shorter than their OAGB, and the stapler line was approximately 4cm away from the greater curvature. It must be considered that this stomach had a greater curvature plication that caused the greater curvature tissue to be thicker; consequently, the lumen of gastric remnant after creating the gastric pouch was more stretched than its external appearance. This condition alongside the adhesion of omentum to the narrowest area of the remnant can cause the obstruction and rotation of gastric remnant. During the conversion procedure, we tried to take care of the remnant vascularization, since we knew that in the previous operations the surgeon was required to perform short gastric vessels ligation. No signs of ischemia appeared at any moment during our surgery. Considering the neovascularization, we decided to leave the gastric remnant in situ.

As described in the literature, gastric remnant dilatation is a postoperative complication, and obstruction of jejunojejunostomy with biliopancreatic limb and remnant dilation is the most common cause.9–11 Early diagnosis is necessary to prevent staple line disruption and, consequently, an abdominal disaster with possible fatal outcome. This patient underwent a revisional surgery, which, as it is well-known, might result in more complications.9 Based on this case, we recommend resecting the gastric remnant in any gastric plication revisional surgery because it could be obstructed by the greater curvature plication inside the remnant.

Our patient presented typical symptoms of small bowel obstruction: persisting abdominal pain, tachycardia, vomits, bloating, fullness, and discomfort. Unfortunately, at that moment, we did not have a computed tomography (CT) scan available. For this reason, we decided that performing a diagnostic laparoscopy was preferable to avoid more complications. Even though there are no guidelines to manage this complication, our team acted in the way they thought to be more beneficial for the patient.11 A dilated blinded stomach can make the approach difficult, and a temporal uncompressing gastrostomy might help, as we decided to proceed in this patient. As far as we know, this is the first reported case of isolated gastric remnant dilatation after revisional surgery following gastric grater curvature plication to RYGB. We would like to highlight the importance of early diagnosis of this complication to surgeons for prevention of severe consequences.

Conclusion

Gastric remnant dilation is always a possible complication after RYGB. It is generally caused by biliopancreatic limb obstruction, but the surgeon must consider this diagnostic even in the absence of small bowel dilatation, especially with patients after revisional bariatric surgery. Early diagnosis and management are necessary to avoid severe consequences. The most important lesson should be preventing this complication; therefore, gastric remnant resection should be considered on a case-by-case basis during conversion from gastric greater curvature plication to RYGB. Gastric remnant dilation could be approached safely by laparoscopy, and the final management is the resection of the remnant stomach.

References

- Sugerman HJ, Kellum Jr JM, Reines HD, et al. Greater risk of incisional hernia with morbidly obese than steroid-dependent patients and low recurrence with prefascial polypropylene mesh. Am J Surg. 1996;171(1):80–84.

- Lazzati A, Bou Nassif G, Paolino L. Concomitant ventral hernia repair and bariatric surgery: a systematic review. Obes Surg. 2018;28(9):2949–2955.

- Ching SS, Sarela AI, McMahon MJ, et al. Comparison of early outcomes for laparoscopic ventral hernia repair between nonobese and morbidly obese patient populations. Surg Endosc. 2008;22(10):2244–2250.

- Liang MK, Holihan JL, Itani K, et al. Ventral hernia management: expert consensus guided by systematic review. Ann Surg. 2017;265(1):80–89.

- Regner JL, Mrdutt MM, Munoz-Maldonado Y. Tailoring surgical approach for elective ventral hernia repair based on obesity and National Surgical Quality Improvement Program outcomes. Am J Surg. 2015;210(6):1024–1029; discussion 1029–1030.

- Lo Menzo E, Hinojosa M, Carbonell A, et al. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery and American Hernia Society consensus guideline on bariatric surgery and hernia surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018;14(9):1221–1232.

- Lau B, Kim H, Haigh PI, Tejirian T. Obesity increased the odds of acquiring and incarcerating noninguinal abdominal wall hernias. Am Surg. 201278(10):1118–1121.

- Lee L, Mata J, Landry T, et al. A systematic review of synthetic and biologic materials for abdominal wall reinforcement in concomitanted fields. Surg Endosc. 2014;28(9):2531–2546.

- Birindelli A, Sartelli M, Saverio D, et al. 2017 update of the WSES guidelines for emergency repair of complicated abdominal wall hernias. World J Emerg Surg. 2017;12:37. eCollection 2017.

- Datta T, Eid G, Nahmias N, Dallal RM. Management of ventral hernias during laparoscopic gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008;4(6):754–757.

- Cozacov Y, Szomstein S, Safdie FM, et al. Is the use of prosthetic mesh recommended in severely obese patients undergoing concomitant abdominal wall hernia repair and sleeve gastrectomy? J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218(3):358–362.

- Eid GM, Mattar SG, Hamad G, et al. Repair of ventral hernias in morbidly obese patients undergoing laparoscopic gastric bypass should not be deferred. Surg Endosc. 2004;18(2):207–210.

- Sauerland S, Korenkov M, Kleinen T, et al. Obesity is a risk factor for recurrence after incisional hernia repair. Hernia. 2004;8(1):42–46.

- Praveen Raj P, Senthilnathan P, Kumaravel R, et al. Concomitant laparoscopic ventral hernia mesh repair and bariatric surgery: a retrospective study from a tertiary care center. Obes Surg. 2012;22(5):685–689.

- Praveen Raj P, Gomes RM, Kumar S, et al. Concomitant bariatric surgery with laparoscopic intra-peritoneal onlay mesh repair for recurrent ventral hernias in morbidly obese patients: an evolving standard of care. Obes Surg. 2016;26(6):1191–1194.

- Praveen Raj P, Bhattacharya S, Kumar S, et al. Concomitant intraperitoneal onlay mesh repair with endoscopic component separation and sleeve gastrectomy. J Minim Access Surg. 2018;14(3):256–258.

- Eid GM, Wikiel KJ, Entabi F, et al. Ventral hernias in morbidly obese patients: a suggested algorithm for operative repair. Obes Surg. 2013;23(5):703–709.

Category: Case Report, Past Articles