Far from the “Easy Way Out”: Early Psychological Complications of Bariatric Surgery

by Kasey P.S. Goodpaster, PhD

Dr. Goodpaster is with the Cleveland Clinic Bariatric & Metabolic Institute in Cleveland, Ohio.

Funding: No funding was provided

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Abstract: Bariatric surgery is the most durable and effective treatment option for morbid obesity, and patients often report substantial improvement in health and quality of life. These improvements become more obvious as the initial adjustment period following surgery has passed. However, a significant minority of patients experience psychological complications including but not limited to grieving the loss of food, regrets having surgery, relationship changes, and fear of weight regain. Prevalence and possible explanations for these complications are outlined in this review. Examples of pre- and post-surgical interventions to mitigate psychological complications are provided.

Keywords: Bariatric surgery, obesity, complications, psychology, adjustment, integrated health

Bariatric Times. 2019;16(8):10–11.

Research has consistently demonstrated that bariatric surgery is the most durable and effective treatment for obesity, bringing about improvements in medical comorbidities, including Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), hypertension, and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and, in turn, drastically improving quality of life (QoL). Feeling physically satisfied with less food can be a tremendous relief for individuals who have felt as if they were battling their bodies through countless weight loss attempts over their lifetime with only minimal long-term success.

While one might assume that weight loss, improved health, and increased QoL would improve mood, a minority of patients experience serious psychological complications including, but not limited to, depression,1 suicidality,2 and alcohol abuse,3 particularly after the “honeymoon period” of 1 to 2 years after surgery. Research suggests that worsening mood postsurgery might be due, in part, to a higher level of psychiatric complexity at baseline,4,5 unrealistic expectations about weight loss and the changes it would bring about,6 psychiatric medication malabsorption after surgery,7 and other factors, many of which are yet to be fully understood. Less attention has been devoted to other psychological complications that could occur earlier in the postsurgical adjustment. This review will focus on psychological complications that clinical experience and budding research suggest affect patients within the first few months postsurgery: grieving the loss of food, regrets having surgery, relationship changes, and fear of weight regain.

Grieving the Loss of Food

We eat for many reasons: physical hunger, to soothe negative emotions, to celebrate, to connect socially, and simply because food tastes good. Being on a liquid diet perioperatively often leads to the jarring realization that while there might be less physical hunger, food cues are as present as ever while mental cravings persist. Patients who have undergone bariatric surgery sometimes describe a grieving process as they let go of the role food played in their lives. In one recent study of psychological complications between one and three months postsurgery, approximately five percent of patients endorsed this grieving process.8 Those who felt out of control of their eating prior to surgery might feel disappointed that loss of control persisted postsurgery but perhaps manifested differently (e.g., graze eating). Even patients who did not engage in binge eating or emotional eating before surgery might feel they have lost the ability to eat in whatever manner they choose, particularly at social events in which food is frequently a primary focus. Similar to mourning the loss of a loved one, grieving the loss of food might involve moving through stages of denial, anger, depression, bargaining, and acceptance, not always in a cyclical manner.9

Regrets Having Surgery

For emergency surgeries, patients might be aware of the potential for complications and indeed experience some of these, yet because they felt they had no choice, they are probably unlikely to blame themselves for having surgery. By contrast, despite powerful motivators for pursuing bariatric surgery, it is still considered an “elective procedure,” and patients must carefully weigh the risks and benefits in their particular circumstances. Thus, in the midst of psychological and/or medical complications in the early postsurgical period, patients might ask themselves, “Why did I do this to myself?” or “Why couldn’t I just lose weight without surgery?”

Regrets usually lift as time passes and the anticipated benefits of surgery come to fruition. One study indicated that 6.4 percent of patients have regrets at one month and 4.3 percent at three months postoperation,8 and another study indicated that none of the patients interviewed between five and 24 months postoperation regretted surgery despite mixed outcomes.10 However, until the “rough patch” of the immediate postoperation period passes, patients need support managing mixed emotions about their decision.

Relationship Changes

Even early on after surgery, many patients notice a mix of negative and positive relationship changes. Patients often need to field many questions about weight loss, eating, and surgery that might feel intrusive and increase feelings of vulnerability. Friends and family, some of whom might have weight-related concerns of their own, might feel rejected, left behind, unneeded, or jealous. They might also struggle with expressing their love and appreciation for the patient without food, which could lead to “food pushing” (i.e., “Is that all you’re going to eat?”), intentional or unintentional sabotage, or uncertainty about how to socialize when food is no longer the primary focus.

Research suggests that divorce and separation are more common in patients who undergo bariatric surgery than in the general population. However, the strongest predictor of postsurgical divorce is poor or tense relationships before surgery, suggesting that patients might feel empowered to leave unhealthy relationships.11 Additionally, compared to those with obesity who do not undergo surgery, patients who do undergo bariatric surgery who were single at baseline are more likely to enter into new romantic relationships and become married following surgery.11 Potential positive relationship changes include:

- Increased physical ability to pursue new or renewed interests, which could then lead to more pleasurable time spent with friends and family

- Broader support network, including other patients who have undergone bariatric surgery

- Increased self-confidence and improved body image, leading to better intimacy.

- Individual and/or couples therapy can help patients navigate relationship changes, improve assertive communication, and broaden social support networks.

Fear of Weight Regain

By the time patients decide to pursue bariatric surgery, they have tried an average of 15 diets, with only short-term success and ultimately continued weight gain.12 Bariatric surgery can then seem like a “last resort,” and the pressure for the surgery to “work” is intense. This pressure could be compounded by perceived or actual judgment from others who view surgery as “the easy way out.” After faster and more noticeable weight loss, patients might face scrutiny about how much they lost, how they lost it, what they are eating, and if they are going to regain the weight they lost. Further, weight loss plateaus, a normal part of a more step-wise weight loss progression, can be reminders of the frustrating rollercoaster of weight loss and regain on diets and lead to alarm or discouragement. Patients might assume they are doing something wrong because they lost weight faster on a previous fad diet.

In contrast to the other psychological complications previously mentioned, fear of weight regain increases over time (14.3% at one month, 20.7% at three months postoperation).8 Incidentally, while some mild anxiety might increase motivation for continued healthy eating habits, more severe symptoms can feel paralyzing or lead to increased emotional eating. Thus, it is key to help patients break down negative thought patterns and remember that they didn’t fail diets, the diets failed them, and bariatric surgery is much more likely to bring about the long-term outcomes they desire.

Implications

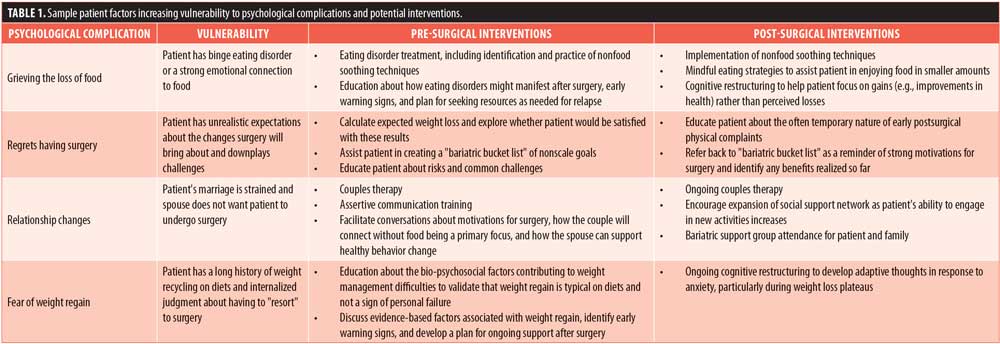

Mitigating psychological complications involves support from the bariatric team both before and after surgery. Before surgery, patients are often justifiably excited and optimistic about the many positive changes the surgery is expected to bring about, and some might downplay the potential for distress. However, minimizing the potential for future difficulties sets patients up for surprises and frustration if/when challenges do arise. The behavioral health evaluation can be the ideal forum for identifying a patient’s individual vulnerabilities to developing psychological complications, as well as the strengths they can harness to assist in the emotional adjustment. Table 1 includes examples of factors that the behavioral health provider might identify as increasing vulnerability to developing psychological complications, as well as possible pre- and postsurgical interventions.

The behavioral health provider will likely take the lead in providing any presurgical interventions needed to prevent postsurgical adjustment problems, but ideally, all bariatric team members should reinforce realistic expectations about the “good, bad, and the ugly” surrounding surgery. After surgery, regular follow-up with the bariatric team, including the behavioral health provider, assists in early identification and treatment of psychological complications. Bariatric programs could benefit from developing and administering brief questionnaires inquiring about psychological complications for easier identification of the most pressing challenges. Shared appointments and support groups offer the added benefit of helping patients to feel validated when they realize they are not alone in their struggles.

Conclusion

What is clear from this small sampling of psychological complications is that bariatric surgery is far from the “easy way out.” Patients must work as hard, if not harder, than on diets, with the added challenge of psychological/emotional changes that can feel unexpected and isolating. After the first few months, patients usually report that they have settled into their “new normal,” but choosing bariatric surgery is embarking on a life-long learning process about how to handle a different relationship with food and the body, underscoring the need for multidisciplinary support indefinitely. Bariatric providers are encouraged to educate patients about potential challenges before surgery, inquire about psychological complications afterward, validate difficult experiences, and connect patients to needed resources early in the adjustment period to prevent problems from escalating.

References

- White MA, Kalarchian MA, Levine MD, et al. Prognostic significance of depressive symptoms on weight loss and psychosocial outcomes following gastric bypass surgery: a prospective 24-month follow-up study. Obes Surg. 2015;25:1909–1916.

- Castenada D, Popov VB, Wander P, Thompson, CC. Risk of suicide and self-harm is increased after bariatric surgery—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2019;29:322–333.

- King WC, Chen J, Courcoulas AP, et al. Alcohol and other substance use after bariatric surgery: prospective evidence from a U.S. multicenter cohort study. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13:1392–1402.

- Kalarchian MA, Marcus MD, Levine MD, et al. Psychiatric disorders among bariatric surgery candidates: relationship to obesity and functional health status. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:328–334.

- Mitchell JE, Selzer F, Kalarchian MA, et al. Psychopathology before surgery in the Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery-3 (LABS-3) Psychosocial Study. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2012;8:533–541.

- Karmali S, Kadikoy H, Brandt ML, Sherman V. What is my goal? Expected weight loss and comorbidity outcomes among bariatric surgery patients. Obes Surg. 2011;21: 595–603.

- Roerig JL, Steffen K. Psychopharmacology and bariatric surgery. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2015;23:463–469.

- Heinberg L, Mohun S, Goodpaster K, et al. Early psychological complications: pre-operative psychological factors predict post-operative regret, fear of failure, and grieving the loss of food. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13:S42–S43.

- Kübler-Ross E. On death and dying. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1969.

- Graham Y, Hayes C, Small PK, et al. Patient experiences of adjusting to life in the first two years after bariatric surgery: a qualitative study. Clin Obes. 2017;7:323–335.

- Bruze G, Holmin TE, Peltonen M. Associations of bariatric surgery with changes in interpersonal relationship status: results from 2 Swedish cohort studies. JAMA Surgery. 2018;153:654–661.

- Gibbons LM, Sarwer D, Crerand CE, et al. Previous weight loss experiences of bariatric surgery candidates: how much have patients dieted prior to surgery? Obesity. 2006;14:71S–76S.

Category: Past Articles, Review