Does the Number of Follow-ups After Single-Anastomosis Duodeno-Ileal Bypass with Sleeve Gastrectomy Influence Weight Loss?

by Amit Surve, MD; Samuel Cottam, CNA; Daniel Cottam, MD; Walter Medlin, MD, FACS; Christina Richards, MD, FACS; and Legrand Belnap, MD

Drs. Surve, Daniel Cottam, Medlin, Richards, and Belnap and Mr. Samuel Cottam are with Bariatric Medicine Institute in Salt Lake City, Utah.

Funding: No funding was provided for this article.

Disclosures: Daniel Cottam, MD, reports personal fees and other from Medtronic and GI Windows, outside the submitted work. All other authors have no conflicts of interests to declare.

Bariatric Times. 2022;19(2):10–12.

Abstract

To date, no manuscripts on the single-anastomosis duodeno-ileostomy with sleeve gastrectomy (SADI-S) procedure have determined if follow-ups affect weight loss outcomes.

Objective: The objective was to determine if the number of follow-up visits influences weight loss.

Methods: A total of 472 patients underwent primary SADI-S surgery. Patients were divided into two groups based on adherence to recommended follow-up visits. Percentage excess weight loss (%EWL) and body mass index reduction (BMIR) were calculated at the first postoperative visit and after 18 months and compared between those who adhered to follow-up and those who did not.

Results: A total of 275 patients were identified. Of the 275 patients, 146 adhered to the follow-up regimen. Percentage EWL was significantly better (p=0.04) in patients that adhered to follow-up, while BMIR was not (p=0.2). In addition, linear regression showed little relation between the number of follow-ups and weight loss.

Conclusion: The frequency of follow-ups does not appear to linearly influence weight loss outcomes after SADI-S.

Keywords: Follow-up, single anastomosis duodeno-ileal bypass with sleeve gastrectomy (SADI-S), success, failure, weight loss

Often, it is assumed that good weight loss programs will help maintain and increase postsurgical weight loss. Because of this assumption, many surgeons carefully design optimal weight loss follow-up programs. However, it is not certain that adherence to these follow-up programs actually results in increased weight loss success or decreased weight loss failure.

Our group has reported on the early-, mid-, and long-term outcomes of the single-anastomosis duodeno-ileal bypass with sleeve gastrectomy (SADI-S).1–10 This operation has shown remarkable effectiveness in comorbidity and weight reduction.1–18

It is assumed by many that adherence to a strict follow-up routine that is designed by surgeons with multidisciplinary follow-up experience is essential to success.19–22 Some studies that have looked at follow-up have concluded that those who followed up had better results than those who did not.23–27 If follow-up is indeed driving better results, what is the optimal follow-up regimen? Also, if follow-up drives weight loss, does this hold true across all bariatric procedures?

The primary aim of this study was to characterize program adherence and see if this increased weight loss after SADI-S. Our secondary aim was to determine if the total number of follow-up visits is related to weight loss.

Methods

Four hundred seventy-two patients underwent primary laparoscopic SADI-S surgery performed by three surgeons from June 2013 through May 2018. The patients’ data were gathered retrospectively from a prospectively kept database. Adherence to postoperative follow-ups was defined as attending at least four of the 1-, 3-, 6-, 12-, and 18-month follow-up appointments. The patients were categorized into two groups: those who adhered to postoperative follow-up (Group A) and those who did not adhere to postoperative follow-up (Group B). Demographic information from both groups was gathered and compared.

All patients were given the same instructions for postoperative care and were asked to follow-up with their doctor at one, three, six, 12, and 18 months. To increase follow-ups, the patients who had not followed-up at 18 months were called to ascertain their weight. The endpoint of this study was weight loss at 18 months. The patient’s first follow-up after 18 months was used to calculate their percentage excess weight loss (%EWL) and body mass index reduction (BMIR). The %EWL was calculated using an ideal body weight corresponding to a BMI of 25kg/m2, and BMIR is the change in BMI from the preoperative period to 18 months.

Additionally, a simple linear regression was done to determine if the total number of follow-ups during the entire postoperative period was correlated with weight loss by %EWL and BMIR. All comparisons were made using t-tests, Fisher exact tests, or Chi-square tests where appropriate. Statistical analysis was performed using R, a language and environment for statistical computing.

Our surgical technique of SADI-S has been described previously.1–3,5,9 Of note, a common channel of 300cm and a sleeve over 40 French bougie was created in all patients.

Results

Of the 472 patients, 275 patients were out 18 months from their bariatric surgery procedure and were identified for analysis. Of these 275 patients, 146 (53%) patients (Group A) adhered to the postoperative follow-up (postoperative 1, 3, 6, 12, 18 months), and 129 patients (47%) did not (Group B). However, the study had a 100 percent follow-up rate at 18 months in each group. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) was the only statistically significant preoperative difference between Group A and Group B, with Group A having higher rates of GERD. No other statistical difference were noted between the two groups (Table 1).

The %EWL for Group A and Group B was 81.7±23.2 percent and 75.8± 24.2 percent, respectively. This difference was significant (p=0.043). The BMIR for Group A and Group B was 19.2±6.5 and 18.1±7.4, respectively. This difference was not statistically significant (p=0.196).

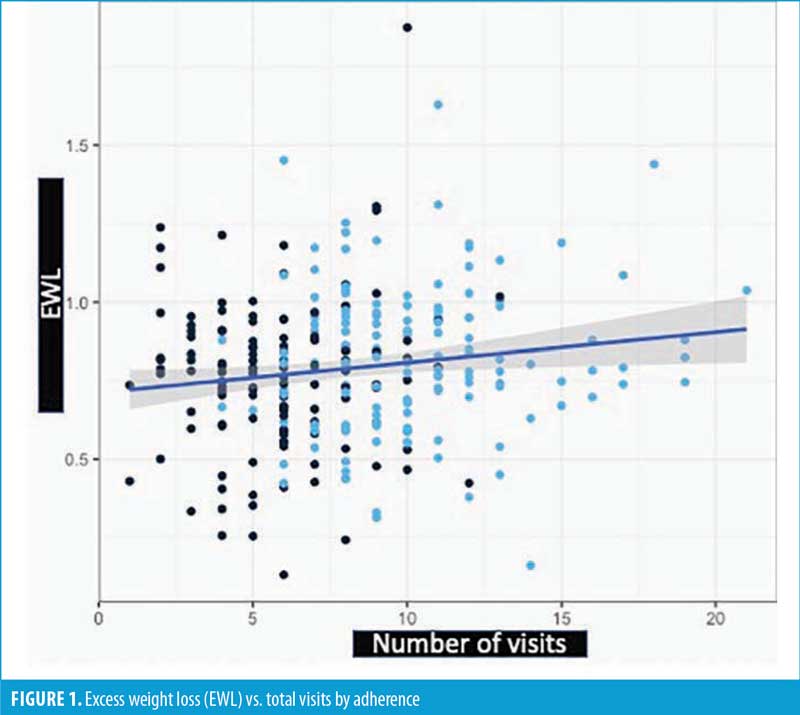

There was a statistically significant positive correlation between the total follow-up visits and %EWL (p=0.017). However, this correlation explained little of the variation in %EWL, as R2=0.021. A graphical representation is shown in Figure 1. The equation for this line is %EWL=71.22%+(0.959%*total follow-up visits).

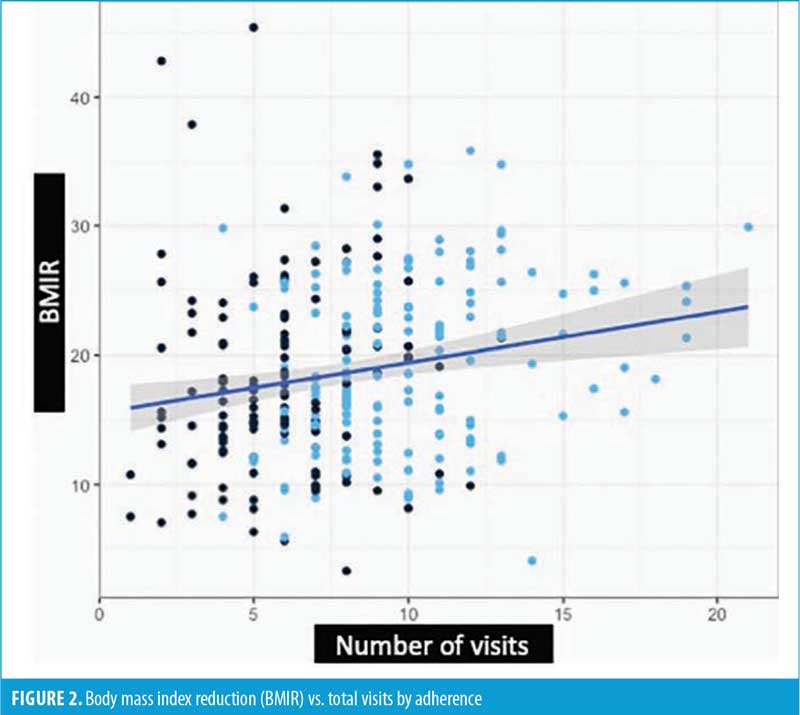

There was a statistically significant positive correlation between the total follow-up visits and BMIR (p=0.001). However, this correlation explained little of the variation in BMIR, as R2=0.039. A graphical representation is shown in Figure 2. The equation for this line is BMIR=15.55+(0.3885*total follow-up visits).

Discussion

The total follow-up visits were significantly correlated with an increase in weight loss, as shown by the linear regression. However, in both cases, the R2 was less than 0.04. This means that less than four percent of the variation in weight loss difference can be explained by the number of follow-up visits. Since this is a retrospective study, we cannot make a conclusion about the efficacy of follow-up visits, but this suggests that the number of follow-up visits alone makes little-to-no impact on a patient’s weight loss.

The %EWL was significantly different between Group A and Group B, while the BMIR was not. This information is contradictory in nature, and is likely explained by small variations in weight loss between the two groups at different BMIs. This contradiction also likely indicates that the effect of program adherence is not strong. If the effect of program adherence is significant but small, we would need a much larger sample size to effectively find the difference between the two groups.

Amongst bariatric surgeons, there is an assumption that continued follow-up and adherence with the program have significant benefits for the patients. We see this view in Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program (MBSAQIP) and Surgical Review Corporation (SRC) standards about follow-up. If it was viewed as unhelpful for weight loss, it would not be as emphasized as it currently is.

In literature, there is conflicting evidence of the effectiveness of follow-up. Numerous papers on both Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) and adjustable gastric banding (AGB) suggest a positive correlation between follow up and weight loss.27,28–32 However, multiple authors have found no significant association. Higa et al33 found that follow-ups are only pertinent to identifying nutritional deficiencies and not associated with increased weight loss. Kedestig et al23 found that patients with multiple follow-ups at two years did not report any additional weight loss over those with fewer follow-ups. Azagury et al34 found that when patients had minimal follow-ups, it was not clinically significant to weight loss. Mehaffey et al35 found no difference in 10-year outcomes between patients with routine clinic visits and those lost to follow-up.

A large and growing amount of presurgery and immediate postsurgery predictive data suggest that preoperative patient demographics and postoperative weight loss velocity can accurately predict long-term weight loss success independent of follow-up visits.23,36–38 When viewing the whole of the data available, we believe that follow-up and program adherence is more likely an associative variable, not a causative variable, for a very small change in weight loss results.

We chose to measure maximal weight loss, which we defined as weight loss at 18 months postoperative. While this is not the case for many patients, previous studies have shown that after 18 months, there is no statistically significant weight loss for sleeve patients as a whole. Therefore, we focused on the cohort as a whole, instead of individual patients, for ease of calculation and to minimize patients’ required visits after 18 months.

Limitations. This was a retrospective study, and as such, we are limited in the strength of conclusions we can make. A prospective trial designed to define adherence with both visits and at-home diet would better answer the question if patient follow-ups have an impact on weight loss through the visits themselves or through diet adherence. However, this study shows that simple adherence to the postoperative follow-up schedule and total visits are likely to have a small, if statistically significant, effect.

The last 20 years have seen a significant push by bariatric societies and programs to emphasize follow-up as one of the key metrics to achieve long-term optimal weight loss. It is a matter of faith for many surgeons that weight-loss failure in the 1990s and 2000s occurred because of the lack of programmatic follow-up. Perhaps this is not the case. This manuscript notes the current push for more follow-up visits might not be warranted after the SADI-S procedure.

Conclusion

Program adherence had conflicting outcomes in the study, with %EWL showing significant differences, while BMIR showed no differences. Additionally, there was no linear correlation between visits and outcomes. This leads us to believe there is no clinically significant way to achieve better weight loss outcomes with more postoperative visits.

References

- Surve A, Cottam D, Medlin W, et al. Long-term outcomes of primary single-anastomosis duodeno-ileal bypass with sleeve gastrectomy (SADI-S). Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2020;16(11):1638–1646.

- Surve A, Cottam D, Richards C, et al. A matched cohort comparison of long-term outcomes of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) versus single-anastomosis duodeno-ileostomy with sleeve gastrectomy (SADI-S). Obes Surg. 2020. Epub ahead of print.

- Surve A, Cottam D, Zaveri H, et al. Single anastomosis duodeno-ileostomy. In: Nguyen N, Brethauer S, Morton J, et al. (eds). The ASMBS Textbook of Bariatric Surgery. 2020; Springer, Cham.

- Surve A, Cottam D, Sanchez-Pernaute A, et al. The incidence of complications associated with loop duodeno-ileostomy after single-anastomosis duodenal switch procedures among 1328 patients: a multicenter experience. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018;14(5):594–601.

- Surve A, Zaveri H, Cottam D, et al. A retrospective comparison of biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch with single anastomosis duodenal switch (SIPS-stomach intestinal pylorus sparing surgery) at a single institution with two year follow-up. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13(3):415–422.

- Surve A, Zaveri H, Cottam D, et al. Mid-term outcomes of gastric bypass weight loss failure to duodenal switch. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12(9):1663–1670.

- Surve A, Zaveri H, Cottam D. Retrograde filling of the afferent limb as a cause of chronic nausea after single anastomosis loop duodenal switch. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12(4):e39–e42.

- Zaveri H, Surve A, Cottam D, et al. A comparison of outcomes of bariatric surgery in patient greater than 70 with 18 month of follow up. Springerplus. 2016;5(1):1740.

- Surve A, Zaveri H, Cottam D. A safer and simpler technique of duodenal dissection and transection of the duodenal bulb for duodenal switch. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12(4):923–924.

- Surve A, Cottam D, Horsley B. Internal hernia following primary laparoscopic SADI-S: the first reported case. Obes Surg. 2020;30(5):2066–2068.

- Mitzman B, Cottam D, Goriparthi R, et al. Stomach intestinal pylorus sparing (SIPS) surgery for morbid obesity: retrospective analyses of our preliminary experience. Obes Surg. 2016;26(9):2098–2104.

- Sánchez-Pernaute A, Rubio MA, Pérez-Aguirre E, et al, Single-anastomosis duodenoileal bypass with sleeve gastrectomy: metabolic improvement and weight loss in first 100 patients. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2013;9(5):731–735.

- Neichoy BT, Schniederjan B, Cottam DR, et al. Stomach intestinal pylorus-sparing surgery for morbid obesity. JSLS. 2018;22(1):e2017.00063.

- Sánchez-Pernaute A, Rubio MÁ, Cabrerizo L, et al. Single-anastomosis duodenoileal bypass with sleeve gastrectomy (SADI-S) for obese diabetic patients. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2015;11(5):1092–1098.

- Moon RC, Kirkpatrick V, Gaskins L, et al. Safety and effectiveness of single- versus double-anastomosis duodenal switch at a single institution. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2019;15(2):245–252.

- Nelson L, Moon RC, Teixeira AF, et al. Safety and effectiveness of single anastomosis duodenal switch procedure: preliminary results from a single institution. Arq Bras Cir Dig. 2016;29(Suppl 1):80–84.

- Enochs P, Bull J, Surve A, et al. Comparative analysis of the single-anastomosis duodenal-ileal bypass with sleeve gastrectomy (SADI-S) to established bariatric procedures: an assessment of 2-year postoperative data illustrating weight loss, type 2 diabetes, and nutritional status in a single US center. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2020;16(1):24–33.

- Surve A, Rao R, Cottam D, et al. Early outcomes of primary SADI-S: an Australian experience. Obes Surg. 2020;30(4):1429–1436.

- Puzziferri N, Roshek TB, Mayo HG, et al. Long-term follow-up after bariatric surgery: a systematic review. JAMA. 2014;312(9):934–942.

- Shoar S, Mahmoudzadeh H, Naderan M, et al. Long-term outcome of bariatric surgery in morbidly obese adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 950 patients with a minimum of 3 years follow-up. Obes Surg. 2017;27(12):3110–3117.

- Karmali S, Kadikoy H, Brandt ML, et al. What is my goal? Expected weight loss and comorbidity outcomes among bariatric surgery patients. Obes Surg. 2011;21(5):595–603.

- Lee W-J, Almulaifi A, Chong K, et al. Bariatric versus diabetes surgery after five years of follow up. Asian J Surg. 2016;39(2):96–102.

- Kedestig J, Stenberg E. Loss to follow-up after laparoscopic gastric bypass surgery – a post hoc analysis of a randomized clinical trial. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2019;15(6):880–886.

- Montastier E, Chalret du Rieu M, Tuyeras G, et al. Long-term nutritional follow-up post bariatric surgery. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2018;21(5):388–393.

- Harper J, Madan AK, Ternovits CA, et al. What happens to patients who do not follow-up after bariatric surgery? Am Surg. 2007;73(2):181–184.

- Belo GQMB, Siqueira LT, Melo Filho DAA, et al. Predictors of poor follow-up after bariatric surgery. Rev Col Bras Cir. 2018;45(2):e1779.

- Vidal P, Ramon JM, Goday A, et al. Lack of Adherence to follow-up visits after bariatric surgery: reasons and outcome. Obes Surg. 2014;24(2):179–183.

- Compher CW, Hanlon A, Kang Y, et al. Attendance at clinical visits predicts weight loss after gastric bypass surgery. Obes Surg. 2012;22(6):927–934.

- Kim HJ, Madan A, Fenton-Lee D. Does patient compliance with follow-up influence weight loss after gastric bypass surgery? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2014;24(4):647–651.

- Gould JC, Beverstein G, Reinhardt S, Garren MJ. Impact of routine and long-term follow-up on weight loss after laparoscopic gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2007;3(6):627–630; discussion 630.

- Vidal P, Ramón JM, Goday A, et al. Lack of adherence to follow-up visits after bariatric surgery: reasons and outcome. Obes Surg. 2014;24(2):179–183.

- Te Riele WW, Boerma D, Wiezer MJ, et al. Long-term results of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding in patients lost to follow-up. Br J Surg. 2010;97(10):1535–1540.

- Higa K, Ho T, Tercero F, et al. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: 10-year follow-up. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2011;7(4):516–525.

- Azagury D, Voller L, Dudley K, et al. Loss to follow-up after bariatric surgery: are lost patients doing better or worse? Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12(7):s145–s146.

- Mehaffey HJ, Turrentine FE, Miller MS, et al. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass 10-year follow-up: the found population. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12(4):778–782.

- Mor A, Sharp L, Portenier D, et al. Weight loss at first postoperative visit predicts long-term outcome of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass using Duke weight loss surgery chart. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2012;8(5):556–560.

- Cottam S, Cottam D, Cottam A. Sleeve gastrectomy weight loss and the preoperative and postoperative predictors: a systematic review. Obes Surg. 2019;29(4):1388–1396.

- Cottam S, Cottam D, Cottam A, et al. The use of predictive markers for the development of a model to predict weight loss following vertical sleeve gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2018;28(12):3769–3774.

Category: Original Research, Past Articles