Robotic-assisted Laparoscopic Adjustable Gastric Band Removal with Roux-en-Y Anatomy for Band Erosion

by Carolyn G. Judge, USN, MC; Christopher G. Yheulon, MD, FACS; and Gordon Wisbach, MD, MBA, FACS, FASMBS

by Carolyn G. Judge, USN, MC; Christopher G. Yheulon, MD, FACS; and Gordon Wisbach, MD, MBA, FACS, FASMBS

Drs. Judge and Yheulon are with the Tripler Army Medical Center in Honolulu, Hawaii. Dr. Wisbach is with the Naval Medical Center San Diego in San Diego, California.

Funding: No funding was provided for this article.

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Bariatric Times. 2021;18(9):9–11.

Abstract

Background: Laparoscopic adjustable gastric bands (LAGB) have fallen out of favor for the surgical treatment of morbid obesity because of their inferior weight loss to alternative procedures, as well as their high rates of complications, including but not limited to band erosion. Although endoscopic removal is the preferred approach for the management of LAGB erosion with or without migration, it is not always successful. Rather than wait for erosion to progress and perhaps allow for endoscopic removal, minimally invasive surgical options can be employed to treat the problem immediately. Definitive removal at the time of discovery is imperative to prevent additional complications. In this article, we report a case of a 50-year-old woman with a remote history of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) for obesity with interval placement of an LAGB for the management of gastric reflux. She was found to have band erosion six years after initial placement, which required surgical intervention following failed endoscopic management. This case represents the only known reported case of gastric band erosion in the setting of Roux-en-Y anatomy.

Laparoscopic adjustable gastric bands (LAGB) were the most common bariatric procedure in the 1990s but have seen a significant decline, perhaps due to more stringent and invasive follow-up requirements, inferior weight loss as compared to the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) and the sleeve gastrectomy (SG), and a greater incidence of revisional surgery.1–3 In 2019, LAGBs made up just 15 percent of bariatric procedures worldwide and have significantly declined, perhaps due to reported complication rates as high as 26 percent.1,4 Common complications include port malfunction and infection, hernias, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and pouch dilation.4, 5 More severe complications include band erosion, slippage, gastric perforation, and intragastric migration.4,6

A study by Trujillo et al7 in 2016 demonstrated the need for definitive removal of lap bands in 54.8 percent of patients in favor of conversion to gastric bypass secondary to the following: leakage, 21.9 percent; slipping, 20.5 percent; and insufficient weight loss, 12.3 percent. Significantly, the annual band removal rate is six percent, with two-thirds of that cohort requiring revisional surgery afterwards.8 Revisional surgery is defined as all procedures performed in patients with a previous LAGB, such as repositioning/removal, port repositioning/removal, and conversions to SG or RYGB.9

Band erosion was first described in 1998, and the incidence had been reported from 0.2 percent to 28 percent.9–14 Today, that range is more consistently 2 to 4 percent.4,10 The average time between primary surgery and diagnosed erosion is almost five years, but the rate of erosion has been shown to be highest in the first two years and decreases over time.6,9,14

Case Report

Case Report

A 50-year-old woman with a remote history of RYGB for obesity, which was complicated by gastric reflux, was managed by interval placement of an LAGB. She presented with subacute left abdominal pain localized to one inch below her subcutaneous port site, nausea, and emesis. Her exam was notable only for a small firm mass in the left upper quadrant without overlying erythema or fluctuance. A computerized tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen demonstrated inflammatory changes surrounding the gastric band without evidence of abscess, obstruction, internal hernia, anastomotic leak, or free air. Her symptoms were attributed to constipation, given a high stool burden without evidence of alternate pathology in the setting of a recent colonoscopy aborted for inadequate preparation.

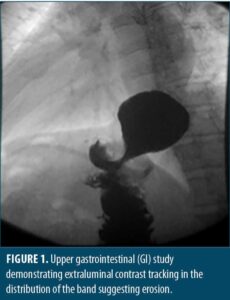

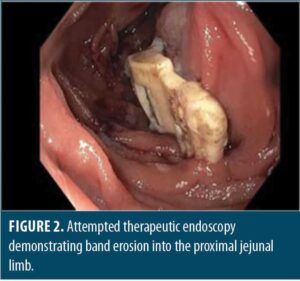

She was referred to bariatric surgery where she underwent a diagnostic endoscopy, which visualized erosion of the gastric band into the proximal roux limb. Further study by upper gatrointestinal (GI) series demonstrated tracking of contrast along the LAGB consistent with known pathology. The access port was exposed and removed by sharp dissection and electrocautery. Attempts were made to remove the band endoscopically. Using a sphincterotome, a 0.035in wire was wrapped around the band and retrieved with raptor forceps. A metal sheath from an emergency lithotripsy kit was passed over the wire to the level of the band to prevent mucosal injury. The wire and sheath were attached to the emergency lithotripsy kit and slowly cranked under endoscopic visualization, resulting in the cutting of what was determined to be the inflating tube, not the band. Two additional attempts were made to cut the band in this manner, which resulted in the wire breaking. Attempts to unbuckle the band using a snare were also unsuccessful, and the decision was made to convert to a minimally invasive robotic-assisted laparoscopic approach.

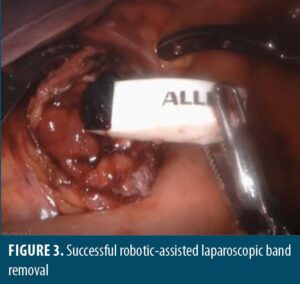

Upon entry into the abdomen, gastric bypass anatomy was noted without injury, pathology, or band visualization, except tubing along the left upper abdomen with associated inflammatory changes. An enterotomy was made along the proximal roux limb using scissor electrocautery, which allowed for visualization of the LAGB buckle. The gastric band was found to be eroding into the posterior proximal roux limb, just past the gastrojejunal anastomosis. Unbuckling was accomplished with subsequent removal through the anterior roux limb enterotomy and ultimately via the 12mm trocar. Removal was uncomplicated, and the enterotomy was closed with a two layer 3-0 vicryl suture with a v-loc closure, followed by a negative air leak test. Proceeding laparoscopically, the left abdominal port was upsized to 12mm to allow for band removal via the corresponding trocar, followed by drain placement and fascial closure with a 0 vicryl suture using an endoclose device. The procedure was uncomplicated, and the patient tolerated it well.

On postoperative Day 1, the patient noted significant left upper quadrant abdominal pain, which was evaluated by acute abdominal series without significant finding. Her pain was successfully medically managed, her diet was advanced, and she was discharged the following day without issue. No postoperative contrast studies were performed due to the patient’s reassuring clinical picture. She developed an abdominal wall abscess at the port-incision on postoperative Day 7, which was drained in the emergency department. Perioperative antibiotics and antithrombotic medication, as well as 24-hour intravenous antibiotics were given. She has had no other complications and continues to do well to date.

Discussion

Discussion

Band erosion is a serious complication of LAGB placement. There have been multiple case reports of small bowel obstruction and even one case of migration to the large bowel with rectal transit.15–19 Intragastric migration has also been shown to cause intra-abdominal abscess, vascular injury resulting in life-threatening hemorrhage, peritonitis, and sepsis.20–25 Complications in some cases have been severe enough to require a total gastrectomy.24, 26

Band erosion is most commonly diagnosed through screening endoscopy and might be associated with loss of satiety, port-site infection, and weight recidivism.6,12,13,20,27,28 Silecchia et al29 proposed a screening upper endoscopy every four months in patients with known LAGB, based on their diagnosis of band erosion in 7.5 percent of their patients, all of whom were asymptomatic. A CT scan is generally not sensitive enough to detect band erosion, but suggestive findings include a perigastric abscess and extraluminal air.13,30

Factors influencing the method and timing of removal include the patient’s clinical presentation, the extent of the band erosion, secondary complications, the equipment available, and the surgeon’s experience. It is generally recommended to remove the band at the time erosion is diagnosed. Band erosion does not necessarily require emergency surgical removal and will allow for endoscopic surveillance as dictated by the clinical scenario.29

Factors influencing the method and timing of removal include the patient’s clinical presentation, the extent of the band erosion, secondary complications, the equipment available, and the surgeon’s experience. It is generally recommended to remove the band at the time erosion is diagnosed. Band erosion does not necessarily require emergency surgical removal and will allow for endoscopic surveillance as dictated by the clinical scenario.29

Early erosion is thought to be due to procedural mircoperforations, which might also contribute to gastric wall perforation.29,31–33 Late erosion is thought to be due to relative gastric wall ischemia, which is possibly due to direct pressure of the band, compromised blood supply following more aggressive dissection, the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs), or smoking and alcohol.27,32 Increased pressure secondary to rapid filling or overfilling might also promote erosion; however, erosions have been observed in uninflated bands.34,35 Inclusion of excess gastric wall during placement or ingestion of large food boluses in the initial postoperative period might also be a contributing factor.12

The data at this time suggests band erosion might be more closely related to infection or intraoperative surgical damage than foreign body reaction.33 In a histological study examining fibroadipose tissue in the immediate vicinity of the band, no cases of foreign body granulomatous reaction were observed, nor were silicone inclusions found within the inflammatory cells.33 Protracted port-site infection has been shown to be the most common clinical manifestation of band erosion; it has been observed to be as high as 16.5 percent in patients who experienced an erosion, compared to the anticipated rate of postoperative infection at this site of 0.36 percent.13,27,36 Additionally, there is evidence that systemic infection (cholecystitis, pancreatitis, diverticulitis) might also be related to band erosion.37 The postoperative port-site infection in this case was likely due to bacterial seeding in the setting of band erosion and might have been prevented by delayed closure.

Hepatomegaly might predispose patients to operative trauma and has been associated with higher rates of conversion and abortion.38,39 Suture tension might also be a contributing factor, as the erosions typically correlate with the ends of the suture lines.13 Additionally, surgeon inexperience has been consistently demonstrated to correlate with incidence of band erosion.6,14,29,38,39 A particularly striking study demonstrated an incidence of 4.7 percent in the first 300 cases of LAGB placement versus 0.53 percent in the last 565.6

There are two techniques used to place an LAGB: the pars flaccida (PF) and the perigastric (PG) technique. The PG technique involves a potentially more dangerous dissection and seats the band lower than the PF technique.40 While both are associated with equal and substantial weight loss, as well as major improvements in metabolic syndrome and quality of life, the PF technique has been shown to be easier to perform and has fewer complications.26,40–42 Band erosion has been demonstrated to be as high as 8.77 percent and 1.07 percent within PG and PF cohorts, respectively, perhaps because of lesser microtrauma and a preserved lesser curve fat.13,43

In symptomatic individuals, immediate removal of the band might decrease the risk of further complications.5 Endoscopic removal has been demonstrated to be safe and effective with low rates of complications, even in advanced cases complicated by intragastric migration.5,9,20,28,44–46 An experienced endoscopic team with advanced skills and a surgical suite to remove the access port are required. Immediate endoscopic removal of eroded bands has been shown to be effective even when the erosion is only partial, but generally, at least 50 percent of the band, as well as the buckle, must be eroded into the gastric lumen for endoscopic removal to be successful.9,28,47,48 Expectant management introduces the risk that erosion will not progress, owing to the decreased pressure with the loss of luminal integrity.49 This technique is acceptable only in an asymptomatic and informed patient intended to be surveilled endoscopically.43 In patients with limited erosion and poorly controlled pain, an endoscopic incision overlying the area covering the band near the erosion might alleviate symptoms and hasten the process, thereby facilitating earlier removal.50

Endoscopic success rates range from 77 to 94 percent, with complications ranging from 0 to 10 percent, the most common being symptomatic pneumoperitoneum.9,20,47,51 While 85 percent of endoscopic removal attempts are successful on the first try, more than one attempt might be needed.47,50 Endoscopic failure is most commonly due to perigastric sutures and adhesions, as well as complications with the cutting wire.12,51 Should endoscopic therapy fail, laparoscopic removal has been demonstrated to be safe.48

Should replacement of the band be desired, it is recommended that the patient wait three months after removal to allow inflammation to settle.14,43 Interestingly, re-banding has been shown to result in acceptable weight loss, but it is associated with a high secondary failure rate and recurrent erosion, with rates as high as 17 percent, thought to be due to relative ischemia of tissue from the previous erosion.7,13,20 Additionally, gastric bypass procedures have been shown to not only affect greater weight loss but also to more effectively control comorbidities.52

Conclusion

Band erosion is a severe complication of LAGB placement. The presentation of this complication is variable, and the etiology is likely multifactorial. It most commonly presents with port-site infection and should be managed with immediate band removal using the preferred technique. Endoscopic therapy is generally successful in patients with altered anatomy or in patients where only a small portion of the band is eroded. Minimally invasive techniques including laparoscopy, robotic-assisted procedures, and hybrid procedures, as well as expectant management might be considered. Given the known complications and inferior weight loss of LAGB as compared to RYGB and SG, as well as the high rates of recurrent erosions following rebanding procedures after primary erosion, conversion to an alternate bariatric procedure should be considered in LAGB patients who have experienced erosion as a staged procedure.

References

- O’Brien PE. The laparoscopic gastric band technique of placement. In: Fischer, J. E. (ed.) Fischer’s Mastery of Surgery, Seventh Edition. Wolters Kluwer (Philadelphia). 2019;2:1198–1203.

- Hutter MM, Schirmer BD, Jones DB, et al. First report from the American College of Surgeons–Bariatric Surgery Center Network: laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy has morbidity and effectiveness positioned between the band and the bypass. Ann Surg. 2011;254(3):410.

- Weber M, Müller M, Bucher T, et al. Laparoscopic gastric bypass is superior to laparoscopic gastric banding for treatment of morbid obesity. Ann Surg. 2004;240(6):975.

- Hota P, Caroline D, Gupta S, Agosto O. Laparoscopic adjustable gastric band erosion with intragastric band migration: a rare but serious complication. Radiol Case Rep. 2018;13(1):76–80.

- Aarts EO, van Wageningen B, Berends F, et al. Intragastric band erosion: experiences with gastrointestinal endoscopic removal. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(5):1567.

- Cherian PT, Goussous G, Ashori F, Sigurdsson A. Band erosion after laparoscopic gastric banding: a retrospective analysis of 865 patients over 5 years. Surg Endosc. 2010;24(8):2031–2038.

- Trujillo MR, Muller D, Widmer JD, et al. Long-term follow-up of gastric banding 10 years and beyond. Obes Surg. 2016;26(3):581–587.

- Lazzati A, De Antonio M, Paolino L, et al. Natural history of adjustable gastric banding: lifespan and revisional rate. Ann Surg. 2017;265(3):439–445.

- Quadri P, Gonzalez-Heredia R, Masrur M, et al. Management of laparoscopic adjustable gastric band erosion. Surg Endosc. 2017;31(4):1505–1512.

- Himpens J, Cadière G-B, Bazi M, et al. Long-term outcomes of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. Arch Surg. 2011;146(7):802–807.

- Weiner R, Emmerlich V, Wagner D, Bockhorn H. Management and therapy of postoperative complications after “gastric banding” for morbid obesity. Chir Z Alle Geb Oper Medizen. 1998;69(10):1082–1088.

- Mozzi E, Lattuada E, Zappo MA, et al. Treatment of band erosion: feasibility and safety of endoscopic band removal. Surg Endosc. 2011;25(12):3918–3922.

- Brown WA, Egberts KJ, Franke-Richard D, et al. Erosions after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding: diagnosis and management. Ann Surg. 2013;257(6):1047–1052.

- Egberts K, Brown WA, O’Brien PE. Systematic review of erosion after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. Obes Surg. 2011;21(8):1272–1279.

- Taskin M, Zengin K, Unal E. Intraluminal duodenal obstruction by a gastric band following erosion. Obes Surg. 2011;11(1):90–92.

- Abeysekera A, Lee J, Ghosh S, Hacking C. Migration of eroded laparoscopic adjustable gastric band causing small bowel obstruction and perforation. Case Rep. 2017;2017:1–3.

- Zengin K, Sen B, Ozben V, Taskin M. Detachment of the connecting tube from the port and migration into jejunal wall. Obes Surg. 2006;16(2):206–207.

- Egbeare DM, Myers AF, Lawrance RJ. Small bowel obstruction secondary to intragastric erosion and migration of a gastric band. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12(5):983–984.

- Bassam A. Unusual gastric band migration outcome: distal small bowel obstruction and coming out per-rectum. Pan Afr Med J. 2012;13(59).

- Chisholm J, Kitan N, Toouli J, Kow L. Gastric band erosion in 63 cases: endoscopic removal and rebanding evaluated. Obes Surg. 2011;21(11):1676–1681.

- Wylezol M, Sitkiewicz T, Gluck M, et al. Intra-abdominal abscess in the course of intragastric migration of an adjustable gastric band: a potentially life-threatening complication. Obes Surg. 2006;16(1):102–104.

- Rao AD, Ramalingam G. Exsanguinating hemorrhage following gastric erosion after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. Obes Surg. 2006;16(12):1675–1678.

- Iqbal M, Manjunath S, Seenath M, Khan A. Massive upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: an unusual presentation after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding due to erosion into the celiac axis. Obes Surg. 2008;18(6):759–760.

- De Roover A, Detry O, Coimbra C, et al. Pylephlebitis of the portal vein complicating intragastric migration of an adjustable gastric band. Obes Surg. 2006;16(3):369–371.

- Campos J, Ramos A, Galvão Neto M, et al. Hypovolemic shock due to intragastric migration of an adjustable gastric band. Obes Surg. 2007;17(4):562–564.

- Dargent J. Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding: lessons from the first 500 patients in a single institution. Obes Surg. 1999;9(5):446–452.

- Abu-Abeid S, Keidar A, Gavert N, et al. The clinical spectrum of band erosion following laparoscopic adjustable silicone gastric banding for morbid obesity. Surg Endosc. 2003;17(6).

- Regusci L, Groebli Y, Meyer JL, et al. Gastroscopic removal of an adjustable gastric band after partial intragastric migration. Obes Surg. 2003;13(2):281–284.

- Silecchia G, Restuccia A, Elmore U, et al. Laparoscopic adjustable silicone gastric banding: prospective evaluation of intragastric migration of the lap-band. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2001;11(4):229–234.

- Hainaux B, Agneessens E, Rubesova E, et al. Intragastric band erosion after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding for morbid obesity: imaging characteristics of an underreported complication. Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184(1):109–112.

- Bilkhu A, Harvey H, Davies JB, et al. Laparoscopic repair of a migrated adjustable gastric band connecting tube with colonic erosion. J Surg Case Rep. 2017;2017(5):rjx089.

- Meir E, Van Baden M. Adjustable silicone gastric banding and band erosion: personal experience and hypotheses. Obes Surg. 1999;9(2):191–193.

- Lattuada E, Zappa MA, Mozzi E, et al. Histologic study of tissue reaction to the gastric band: does it contribute to the problem of band erosion? Obes Surg. 2006;16(9):1155–1159.

- Forsell P, Hallerbäck B, Glise H, Hellers G. Complications following Swedish adjustable gastric banding: a long-term follow-up. Obes Surg. 1999;9(1):11–16.

- Angus LG, Rizvon K, Zhou D, et al. Intra-gastric band erosion from an un-inflated lap-band: a case report. Obes Surg. 2008;18(12):1636–1639.

- Chapman AE, Kiroff G, Game P, et al. Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding in the treatment of obesity: a systematic literature review. Surgery. 2004;135(3):326–351.

- Naim HJ, Gorecki PJ, Wise L. Early lap-band erosion associated with colonic inflammation: a case report and literature review. JSLS. 2005;9(1):102.

- Chevallier J-M, Zinzindohoué F, Douard R, et al. Complications after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding for morbid obesity: experience with 1,000 patients over 7 years. Obes Surg. 2004;14(3):407–414.

- Chelala E, Cadiére GB, Favretti F, et al. Conversions and complications in 185 laparoscopic adjustable silicone gastric banding cases. Surg Endosc. 1997;11(3):268–271.

- O’Brien PE, Dixon JB, Laurie C, Anderson M. A prospective randomized trial of placement of the laparoscopic adjustable gastric band: comparison of the perigastric and pars flaccida pathways. Obes Surg. 2005;15(6):820–826.

- Ren CJ, Fielding GA. Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding: surgical technique. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech. 2003;13(4):257–263.

- Weiner R, Bockhorn H, Rosenthal R, Wagner D. A prospective randomized trial of different laparoscopic gastric banding techniques for morbid obesity. Surg Endosc., 2001;15(1):63–68.

- Nocca D, Frering V, Gallix B, et al. Migration of adjustable gastric banding from a cohort study of 4236 patients. Surg Endosc Interv Tech. 2005;19(7):947–950.

- Baldinger R, Mluench R, Steffen R, et al. Conservative management of intragastric migration of Swedish adjustable gastric band by endoscopic retrieval. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53(1):98–101.

- Rodarte-Shade M, Barrera GT, Arredondo JHF, Diaz RR. Hybrid technique for removal of eroded adjustable gastric band. JSLS. 2013;17(2):338.

- Weiss H, Nehoda H, Labeck B, et al. Gastroscopic band removal after intragastric migration of adjustable gastric band: a new minimal invasive technique. Obes Surg. 2000;10(2):167–170.

- Neto MPG, Ramos AC, Campos JM, et al. Endoscopic removal of eroded adjustable gastric band: lessons learned after 5 years and 78 cases. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2010;6(4):423–427.

- Kohn GP, Hansen CA, Gilhome RW, et al. Laparoscopic management of gastric band erosions: a 10-year series of 49 cases. Surg Endosc. 2012;26(2):541–545.

- Vantienen B, Vaneerdeweg W, D’Hoore A, et al. Intragastric erosion of laparoscopic adjustable silicone gastric band. Obes Surg. 2000;10(5):474–476.

- Campos JM, Evangelista LF, Galvão Neto MP, et al. Small erosion of adjustable gastric band: endoscopic removal through incision in gastric wall. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2010;20(6):e215–e217.

- Dogan ÜB, Akin MS, Yalaki S, et al. Endoscopic management of gastric band erosions: a 7-year series of 14 patients. Can J Surg. 2014;57(2):106.

- Weber M, Müller MK, Michel JM, et al. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, but not rebanding, should be proposed as rescue procedure for patients with failed laparoscopic gastric banding. Ann Surg. 2003;238(6):827.

Category: Case Report, Past Articles