Management of Long-Term Complications of Gastric Banding and Gastric Balloon

by Christine Ren Fielding, MD, FACS, FASMBS

by Christine Ren Fielding, MD, FACS, FASMBS

Dr. Ren Fielding is Professor of Surgery, NYU School of Medicine; Chief, Division of Bariatric/Minimally Invasive Surgery; and Director, NYU Langone Weight Management Program in New York, New York.

Funding: No funding was provided.

Disclosures: The author has no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Abstract: Laparoscopic adjustable gastric band and gastric balloon devices are both options for treating the condition of obesity. By carrying the advantage of being less invasive, these interventions may increase patient acceptance to pursue treatment. Understanding the potential complications which may occur long-term with each of these devices, can help the provider counsel the patient properly on symptoms to be aware of, diagnose them early and provide adequate management.

Keywords: Gastric banding, gastric balloon, complications

Bariatric Times. 2019;16(11):12–16.

Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding and intragastric balloon devices offer different strategies and approaches to managing the condition of obesity. Compared to alternative surgical procedures, both of these devices are less invasive, reversible, and associated with a shorter hospital stay and decreased risk of malnutrition. As with any procedure, however, there can be complications that need to be recognized and treated. This article will address the management of long-term complications of gastric banding and gastric balloon.

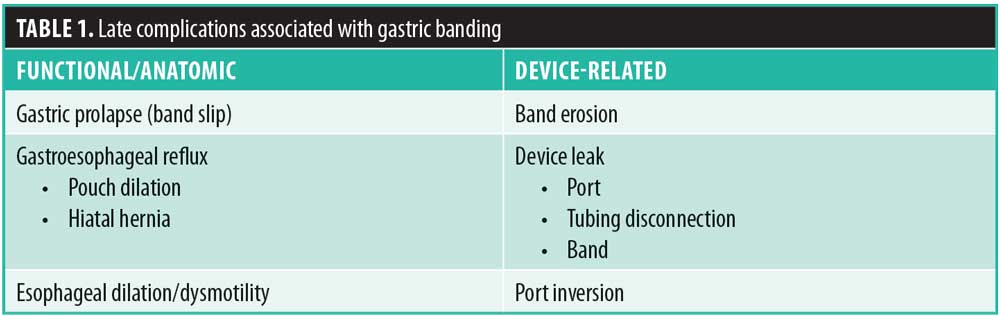

Laparoscopic Adjustable Gastric Banding

The laparoscopic adjustable gastric band (LAGB) involves the surgical placement of an adjustable silicone ring circumferentially around the gastric cardia in an effort to create appetite suppression, increased satiety, and overall decreased food consumption. The band is tightened or loosened by percutaneously injecting saline into a subcutaneous access port that is connected to the band. These band adjustments, in turn, can be modified according to patient symptoms of hunger, sense of fullness, dysphagia, vomiting, or reflux, with the goal being appetite control. If the band is not tightened enough, the patient will experience strong appetite, no satiety, and no weight loss. If the band is too tight, the patient will experience regurgitation, vomiting, heartburn, or nocturnal reflux (Table 1). Understanding these symptoms can guide the clinician with managing the gastric band, as well as recognizing long-term complications.

Band slippage/gastric prolapse. Gastric prolapse, alternatively known as “band slippage,” is a well-known complication of the LAGB. It is defined as prolapse or herniation of some portion of the stomach, most commonly the fundus, cephalad up through the gastric band. Gastric prolapse results in an enlarged gastric pouch and can cause complete or partial outlet obstruction. The rate of gastric prolapse varies, with a reported occurrence between one and 14 percent of patients at an average of 10 months after surgery.1 It remains one of the main indications for reoperation after gastric banding.

Symptoms of gastric prolapse commonly include nocturnal reflux, regurgitation or cough, inability to tolerate oral intake, increased ability to tolerate food with vomiting 2 to 3 hours later, and heartburn. Occasionally, patients can be asymptomatic. Acute onset of epigastric pain is a rare symptom of gastric prolapse and might represent a more severe complication, such as strangulation, leading to gastric ischemia, perforation, or volvulus, which are surgical emergencies requiring immediate operation.

Gastric prolapse can be subdivided into three varieties: anterior, posterior, and concentric. Anterior and posterior prolapse are eccentric “true prolapses” and occur when the stomach herniates up through the band on one side, creating an enlarged asymmetric gastric pouch. The normal position of the gastric band on esophagram is having it point on diagonal toward the patient’s left shoulder, located 1 to 2cm below the gastroesophageal junction, with a column of barium traversing from the esophagus, into the stomach pouch above the band and through the band into the lower stomach. The gastric pouch height and width dimensions should not be much larger than the length of the gastric band (Figure 1A). Instances when the fundus herniates through and above the band and comes to lie anterior to the esophagus are termed anterior prolapse (Figure 1B). Posterior slip occurs when the posterior fundus of the stomach prolapses through the band into the lesser sac.

Concentric prolapse represents a different entity than eccentric prolapse. Concentric prolapse is commonly viewed as dilation of the stomach pouch that lies above the band and could result from over-tightening of the band, patient nonadherence, or chronic volume overload of the pouch. However, concentric dilation could also be due to migration of the stomach from below to above the band and represent an actual mechanical prolapse. Symptoms could be similar to that of a true eccentric gastric band prolapse (e.g., vomiting, reflux, dysphagia), and might include failure to achieve adequate weight loss.

If gastric prolapse is suspected, initial management should include an esophagram to confirm the diagnosis. Barium studies can readily demonstrate slippage, with presence of a dilated gastric pouch or displacement of the band to the lower gastric fundus, body, or even antrum. Often times, a flat plate X-ray of the upper abdomen is useful in screening for slippage. In an anterior–posterior (AP) projection of an abdominal X-ray, the band normally lies about 5cm below the diaphragm, and the phi angle of the band is 45 degrees (phi angle corresponds to the angle between spinal column and the gastric band—normal range is between 4 and 58 degrees) (Figure 2A). Slipped bands tend to be more horizontal in orientation, with a phi angle greater than 58 degrees (Figure 2B). Recent studies in the radiology literature have demonstrated a common radiologic presentation known as the “O-shaped sign,” which occurs when the slipped band also tilts along its horizontal axis and resembles the letter “O” (Figure 2B). If the patient has an obstruction from a slipped band, an air-fluid level also might be present in the dilated pouch.

In a patient with gastric prolapse, the band should be completely deflated. If symptoms resolve, a repeat esophagram should be performed. Sometimes a small band slip will correct itself after the band is emptied. In this case, the band can be retightened gradually, but the patient and clinician should be aware that if symptoms recur, then it is highly likely that the gastric prolapse has recurred, and surgery should be scheduled electively after the band is emptied again. If liquids are not tolerated despite fluid removal from the band, the patient should be rehydrated with intravenous (IV) crystalloid and taken for surgery. Persistent epigastric pain in the presence of gastric prolapse, despite band loosening, is suspect for gastric strangulation and ischemia and is a surgical emergency; this requires immediate surgical intervention.

Surgical intervention involves band revision, replacement, or removal. Band unlocking is another alternative, particularly in a pregnant patient where time under anesthesia and fetal health are most important; the patient then can return for a definitive operation when she is postpartum. Although rarely a surgical emergency, band revision should be performed in a timely manner to avoid development of complications, such as aspiration pneumonia or gastric strangulation. In the operating room (OR), the deflated band should be mobilized by incising the overlying capsule and taking down the previous gastro-gastric plication. This includes the area at the angle of His. If the plication and capsule are not completely cleared at the angle of His, a recurrent slip might ensue. A concomitant conversion surgery to sleeve gastrectomy (SG) or Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) should not be performed at the time of band slip due to the presence of inflamed, thickened, or distorted gastric wall, which could contribute to compromised staple line creation.

Gastroesophageal reflux: pouch dilation and hiatal hernia. Gastroesophageal reflux disease, a common disorder in patients with obesity, is not a contraindication to LAGB placement. On the contrary, the LAGB might function as an anti-reflux barrier in patients with obesity gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). This, in conjunction with routine intraoperative repair of hiatal hernias during LAGB placement, can lead to complete resolution of reflux symptoms after surgery, as well as a decrease in band slippage.2

Postoperatively, a subgroup of patients can develop new onset GERD or worsening of pre-existing reflux symptoms. Studies have shown that the percentage of patients with continued GERD or aggravation of symptoms can be as high as 31.7 percent.3 Symptoms can vary from mild heartburn to severe nocturnal reflux, which can be accompanied by aspiration pneumonia or even new-onset asthma. Symptoms should be managed with antacids and proton-pump inhibitors; however, definitive treatment should be dictated by the physiologic cause of reflux.

Postoperative reflux after LAGB placement can occur by various etiologies, and an esophagram might aid in diagnosis. If the esophagram shows gastric pouch dilation, the band is likely too tight and should be treated with fluid removal. Gastric prolapse might be the culprit, and it can be fixed surgically.

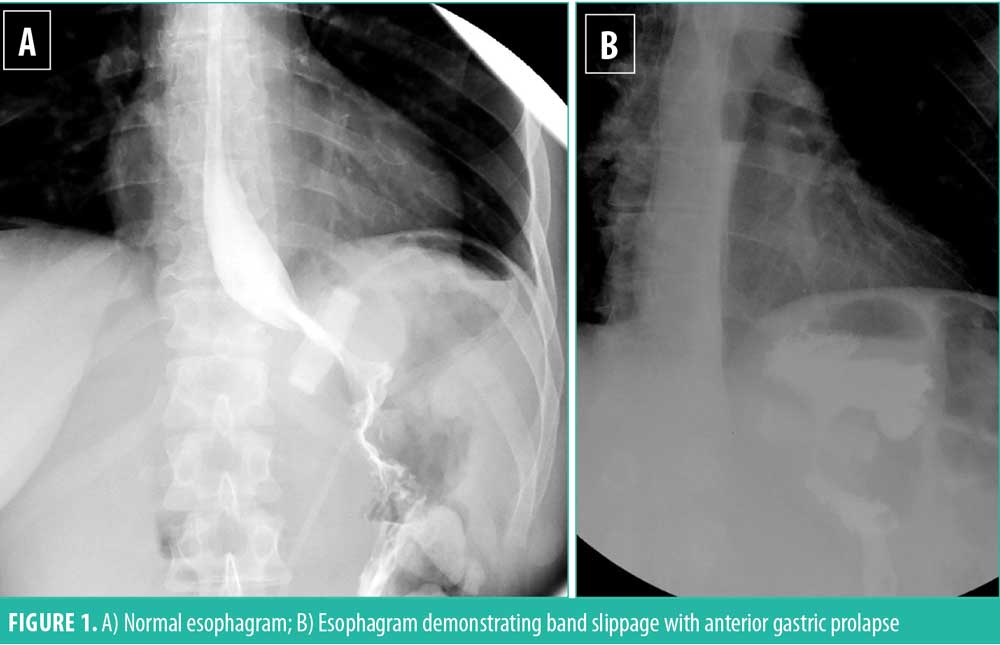

Postoperative GERD might also be due to a pre-existing physiologic condition. If the patient had a hiatal hernia preoperatively that was not noticed or repaired, LAGB might cause exacerbation of hiatal hernia and its symptoms. In fact, subclinical hernias might become more prominent after placement of an adjustable gastric band.4 Therefore, all hiatal hernias should be sought out and primarily repaired during the initial banding procedure. Clinical suspicion that a patient has a hiatal hernia should be made if the band is either too tight or too loose and no middle ground can be found. This refers to the patient developing nocturnal reflux when the band is tightened, and yet not achieving appetite suppression. The patient typically is a “frequent flyer” who comes into the office often to have the band tightened to lose weight, but then returns soon after because of subsequent reflux. This pattern should alert the clinician to send the patient for an esophagram, which sometimes can show an enlarged gastric pouch extending into the mediastinum (Figure 3). An upper endoscopy or a computed tomography (CT) scan can be more specific at identifying a hiatal hernia. In this circumstance, surgical repair with or without band repositioning can solve the problem.

Esophagitis from either frequent regurgitation or pills can affect motility of the distal esophagus, resulting in heartburn or reflux, particularly at night. Behavioral counselling consists of two primary types: 1) eating slowly with thorough chewing of a food bolus to avoid regurgitation, and 2) avoiding swallowing large pills. As such, it is helpful to assist the patient in finding their medications in crushable, chewable, or liquid formulations. In both cases, esophagitis is best treated with temporary band loosening, plus either sucralfate elixir or proton pump inhibitor for 2 to 4 weeks. The band can be subsequently retightened.

Esophageal dilatation. Although esophageal dilatation has been implicated in exacerbating GERD symptoms, the presentation of esophageal dilatation and its associated symptoms are quite broad. Some patients remain asymptomatic, some have decreased satiety, and others might develop reflux. This entity can be on the spectrum of concentric pouch dilation or can progress to psuedoachalasia.5 Similarly, a pre-existing esophageal motility disorder can play a role in the exacerbation of GERD. Some authors postulate that patients with obesity and defective esophageal contractions on manometry might not build up enough esophageal pressure to overcome the outflow resistance created by the LAGB. In addition to reflux, this can lead to esophageal dilatation. For this reason, some physicians advocate for alternative bariatric procedures to be performed in those with preoperative esophageal motility disorders; however, there is no consensus at this time.3

Overall, the current literature on esophageal dilatation is difficult to interpret because different studies use vastly differing definitions for esophageal dilation. The percentages of patients with esophageal dilatation reported in the literature vary widely from 0.5 to 77.8 percent.6 Nonetheless, a few concepts are generally accepted: 1) an adjustable gastric band placed close to the gastroesophageal (GE) junction might cause a relative outlet obstruction, causing the esophagus to function as a reservoir for food, leading to esophageal dilatation, and 2) in most cases, dilatation is at least partly reversible by removing fluid from the lap band. It is advisable to wait at least eight weeks to begin band reinflation. If esophageal dilatation and dysmotility fail to resolve, the band should be removed and possibly converted to an RYGB for weight control. Conversion to SG is not recommended due to the increased intraluminal pressure, which would exacerbate esophageal dysmotility and reflux.

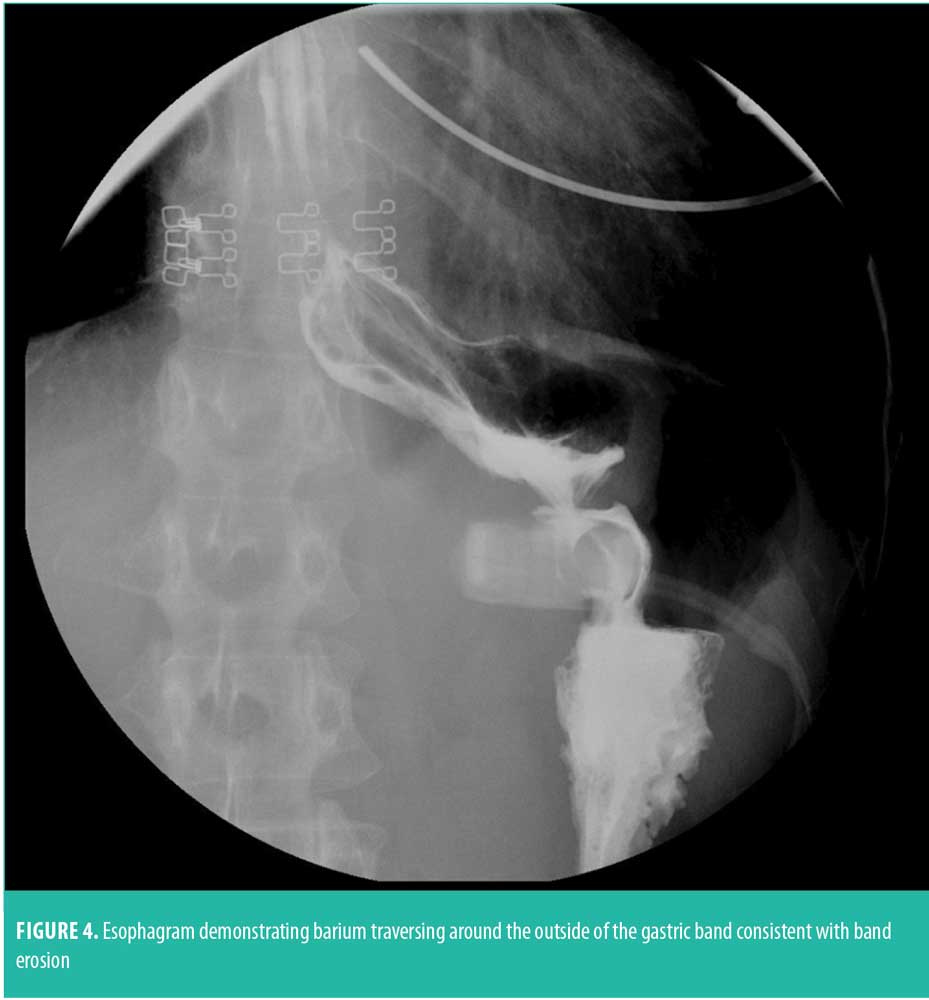

Band erosion. Band erosion is characterized by intragastric band migration, either partial or complete, due to the band eroding through the gastric wall over time. It is a rare complication, occurring in less than one percent of cases. Erosions might present with nonspecific upper abdominal discomfort, weight gain, increased hunger, or loss of satiety despite band adjustment. In some cases, the first indication is a late infection at the port site presenting as cellulitis.

The cause of erosion is unclear and might be due to injury to gastric serosa during the time of band insertion, gastric ischemia from an overly tight band, or ischemia from a prior bariatric procedure causing impaired vascular supply to the stomach. If band erosion is suspected, the patient should have an upper endoscopy to confirm the diagnosis (Figure 4). Band erosion can also be identified on a CT scan or upper gastrointestinal series (UGI) study by passage of barium around the intraluminal portion of the band or around all sides of the band if it has eroded completely into the gastric lumen. Rarely, a completely eroded intraluminal band might migrate distally or proximally causing a high-grade obstruction, which can also be visualized on UGI or CT scan. Band erosion rarely results in peritonitis because of the slow progression, which allows the stomach to heal around the band.

Surgical correction is warranted in a patient diagnosed with erosion. The band can be removed laparoscopically with subsequent repair of the stomach wall. An intraoperative leak test is recommended along with placement of a drain. Replacing a new band or performing another bariatric procedure, such as RYGB or SG at the time of gastric repair is not recommended due to the inflammation of tissue which may compromise wound healing. It is recommended to wait at least six months before replacing the gastric band or performing a different bariatric operation in an attempt to decrease adhesions created by the band erosion.

Successful endoscopic removal of the band has also been performed at some institutions.7 This technique is cost effective and less invasive than laparoscopy; however, the ability to treat free intraperitoneal perforation and other complications is severely limited with this approach. In addition, the entire band including the buckle must be inside the gastric lumen for endoscopic removal to take place, and the access port must be removed separately.

Port and tubing problems. As with any implantable device, there are expected technical complications with the gastric band. Most are not life threatening and can be easily corrected with a minor procedure. A patient’s presenting symptom(s) will vary depending on the type of the device malfunction; the treatment also will vary. Overall, the rate of port and tubing device complications is low, with approximate rate of three percent.8 Port migration might occur and is usually noticed at band adjustments. If the port is flipped upside-down, the membrane cannot be accessed to perform adjustments. An AP and lateral flat plate X-ray can confirm port position. During LAGB placement, the port should be secured to the anterior rectus fascia with permanent sutures. Patients should be discouraged from physical exertion for 4 to 6 weeks after surgery to allow for adequate healing and fixation of the access port to the rectus fascia. If the port does migrate, it can be managed with local wound exploration, port repositioning and fixation. This can be performed under local or general anesthesia.

Port-site infections can also occur but are rare, with a reported frequency of 0.6 percent. Infections are subdivided into early and late varieties. Early infections are infrequent and can be treated initially with oral antibiotics, but if there is a poor response, IV antibiotics should be administered. If the port infection does not respond to antibiotics or recurs, the port should be removed, the tubing capped and replaced into the abdominal cavity, and the wound allowed to heal by secondary intention. Once the wound heals, the tubing can be retrieved laparoscopically and a new port placed in a different location. An untreated port infection could lead to band erosion. Late infections require further evaluation of the band because an infection might indicate band erosion and necessitate band removal. Late, chronic, or recurrent infections might also represent other problems, such as intra-abdominal abscess, enterocutaneous fistula, intracolonic perforation of tubing, or other rare complications.

Another complication of the gastric band access component is breakage or leakage of the port or tubing, which has a reported frequency of 0.6 to 1 percent.8,9 Leakage should be suspected when filling volumes do not correspond with deflating volumes, the fluid appearance is altered, or the patient experiences loss of restriction. Leakage can occur from a variety of locations: 1) break in the tubing, 2) needle perforation of the nonmembrane portion of the port due to attempted adjustments, or 3) cored section of silicone membrane due to prior use of hyperdermic needle rather than noncoring Huber needle. A port leak can be rectified by simple port replacement and reconnection to the existing band. Leakage caused by tubing disconnection or break can be corrected by laparoscopic retrieval of tubing, mobilization of the access port, and reconnection of the tubing with a new access port. Of note, radiographic studies, such as an abdominal X-ray, can be helpful to show tubing disconnection, but injecting contrast material into the device and performing an X-ray does not typically provide optimal visualization of the defect.

Leakage can also occur from the band itself. This is usually due to an inadvertent needle puncture to the band in the operating room. Occasionally, a defect in the band material itself can give way to a crease defect in the balloon or a fractured seal between the balloon and band shell, resulting in leak. Leakage can occur from anywhere in the tubing, particularly if there is any angulation due to adhesions. Intraoperative methylene blue injection into the access port can be helpful in revealing location of the leak. Device leakage from either the band or the tubing warrants replacement of the gastric band component only, with reconnection to the existing access port. Regardless of which component is replaced, the corrected system should be checked to ensure that the source of the leak has been addressed, by injecting and retrieving the same amount of saline.

Weight regain and compliance. The LAGB can lead to significant weight loss and improvement in obesity-related comorbidities and quality of life. Mean excess weight loss (EWL) at 10 to 20 years postoperatively has been reported to be approximately 47 percent.8,10 Weight loss is typically gradual and constant over the course of 18 to 30 months, with a target loss of 1 to 2 pounds/week. The distribution of weight loss is heterogeneous and has been shown by the Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (LABS) group to be the following: 62 percent of patients lose 15 percent total weight loss (TWL), with 19 percent losing 35 percent plus TWL and 19 percent losing less than five percent TWL.11

Failure of weight loss or weight regain after LAGB surgery is due to a variety of reasons, and management must be based on the cause of failure. Sometimes it can be a symptom of a band complication. Primary malfunction of the band can cause failure to lose weight or weight regain; these include: device leakage (port, tubing, or band), and band erosion. Band slippage, gastric pouch, or esophageal dilation, which might present with food intolerance, can lead to maladaptive eating of soft high calorie foods and subsequent weight gain. Treatments of these entities are described in earlier portions of this article.

Adherence is critical among postoperative LAGB patients to achieve successful weight loss and avoid complications. These patients require strict postoperative dietary guidelines, which is typically a gradual progression of a liquid diet to puree and fully solid foods, as excess vomiting has been linked to gastric prolapse, pouch dilation, and esophageal dysmotility/dilation. Furthermore, patients are advised not to eat and drink simultaneously to maximize the amount of time the gastric pouch is filled with food. Patients will require dietary counseling even after the immediate postoperative period to successfully adapt their eating habits to the restrictive mechanism of the gastric band. They must be counseled on how to eat slowly and chew foods thoroughly. They also must learn to recognize satiety and when to stop eating because failure to do this can lead to regurgitation. Mindful eating is key to avoiding unpleasant side effects of the band.

Patients must be counseled to avoid high caloric intake in small volumes, such as sugary and sweet foods. Eating greater quantities of high-calorie sweet foods can lead to the failure of weight loss or weight regain. In this scenario, rigorous and repeated dietary and behavioral counselling might be beneficial. Some patients who adopt a maladaptive eating behavior might benefit from band removal and possible revision to another bariatric procedure. In addition, eating out of boredom or habit is one of the most difficult aspects of patients to overcome.

The most common reason for poor weight loss is suboptimal band tightness. Weight loss after LAGB is contingent on band adjustments, which necessitate frequent postoperative visits. Band adjustments should begin 4 to 6 weeks after surgery when the patient is tolerating regular food and can be reassessed every 4 to 6 weeks until the rate of weight loss is at goal levels. Titration of the band’s compression around the stomach will result in optimal appetite suppression and satiety. A band that is too loose will not be effective in portion control, and conversely, a band that is too tight will result in solid food intolerance with subsequent maladaptive eating of soft, high-calorie foods, such as ice cream, chocolate, and sugary beverages. We have found that frequent postoperative visits allow for physical titration of the band and repetitive behavioral and dietary counseling. Any psychosocial factors that prohibit the patient from making postoperative visits for band adjustments can contribute to failure of weight loss. In fact, patients who return more than six times in the first year after LAGB lose an average of 50 percent EWL, compared to 42 percent EWL among those who return six times or fewer.12 It is important to note that, in addition to patient adherence, the surgical practice must also have resources to accommodate the frequent patient follow-up necessary for successful weight loss after gastric banding. Furbetta et al13 showed that by adding an interdisciplinary program, LAGB patients can lose more weight and have decreasing complications.

Intragastric Balloon

The intragastric balloon is a space-occupying device made of thin synthetic material, filled with either saline or air, placed into the stomach lumen by either endoscopy or swallowed as a capsule and then inflated under direct vision. By filling the stomach, the balloon acts to increase satiety by making the patient feel full with a smaller amount of food. There are several gastric balloons on the market, as well as several in development. Due to the gastric acid environment, the balloon wall is at risk for deterioration and leak if it is not removed after one year. Balloon deflation would thus ensue, followed by potential migration out of the stomach into the intestine, causing obstruction (Figure 5).14 For this reason, almost all balloon manufacturers recommend endoscopic removal of the device at six months after implantation. However, it is possible that the balloon leaks and deflates prior to the planned explantation, and therefore, in fluid-filled balloons, many clinicians add methylene blue to the saline that fills the balloon. In this way, if the balloon leaks out saline, the methylene blue is absorbed and excreted through the kidneys, making the urine green in color. The alerted patient can then contact their clinician and schedule endoscopic retrieval of the gastric balloon device within 12 to 24 hours, before it can migrate out of the stomach. Development of a self-deflating balloon that is small enough to either pass through, or have the technology to be absorbed, are presently theoretic in nature and not yet available for use.

Spontaneous hyperinflation of liquid-filled balloons, with either air or liquid, has been reported to occur and might require the need for premature balloon removal. Symptoms include intense abdominal pain, abdominal distension, shortness of breath and vomiting. The etiology of spontaneous hyperinflation is unclear; however, endoscopic balloon removal is the only treatment. Similarly, pancreatitis might occur due to the extrinsic compression by the intragastric balloon in association with dehydration. Supportive care and removal of the gastric balloon when the patient is stabilized is indicated. Rare occurrences of death had been reported in 2017 by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in over 56,000 intragastric balloons implanted worldwide, many of which had unclear etiology.15 Therefore, clinicians must be alert to unusual and persistent symptoms experienced by the gastric balloon patient, that might reflect rare yet dangerous complications.

Because of the importance of balloon removal prior to a year, the patient must be educated on this risk so as to avoid patient nonadherence in returning. Many patients do well with their weight loss after balloon implantation and do not want to have the balloon removed for fear of weight regain, leading them to not return for the explantation procedure. For this reason, the patient should be counselled on a postballoon explantation strategy to ensure continued weight loss, or atleast, prevent weight regain. Starting the patient on pharmacotherapy a month prior to balloon removal can give the patient hope for continued weight loss, and strengthen the doctor–patient relationship, thus decreasing the risk for patient attrition. Common medications that can be used include phentermine, topiramate, bupropion, and liraglutide.

Once the gastric balloon is removed, there are no known long-term complications except for weight gain. If bariatric surgery is considered, it is recommended to wait at least two months after balloon removal, for the stomach to return to its baseline wall thickness and size.

Conclusion

The LAGB and intragastric balloon are implantable devices that assist in weight loss that can be optimized within a multidisciplinary program. Understanding the potential long-term complications can assist in early diagnosis and treatment, with relatively low-morbidity if managed appropriately.

References

- Egan, RJ, Monkhouse SJ, Meredith HE, et al. The reporting of gastric band slip and related complications: a review of the literature. Obes Surg. 2011;21(8):1280–1288.

- Gulkarov I, Wetterau M, Ren CJ, Fielding GA. Hiatal hernia repair at the initial laparoscopic adjustable gastric band operation reduces the need for reoperation. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:1035–1041.

- Klaus A, Gruber I, Wetscher G, et al. Prevalent esophageal body motility disorders underlie aggravation of GERD symptoms in morbidly obese patients following adjustable gastric banding. Arch Surg. 2006;141(3):247–251.

- Azagury DE, Varban O, Tavakkolizadeh A, et al. Does laparoscopic gastric banding create hiatal hernias? Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2013;9(1):48–52.

- Khan A, Ren-Fielding C, Traube M. Potentially reversible pseudoachalasia after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45(9):775–779.

- de Jong JR, Tiethof C, van Ramshorst B, et al. Esophageal dilation after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding: a more systematic approach is needed. Surg Endosc. 2009;23(12):2802–2808.

- Dogan, UB, Akin MS, Yalaki S, et al. Endoscopic management of gastric band erosions: a 7-year series of 14 patients. Can J Surg. 2014;57(2):106–111.

- Carelli AM, Youn HA, Kurian MS, et al. Safety of the laparoscopic adjustable gastric band: 7-year data from a U.S. center of excellence. Surg Endosc. 2010;24(8):1819–1823.

- Ponce J, Paynter S, Fromm R. Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding: 1,014 consecutive cases. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;201(4):529–535.

- O’Brien P, Hindle A, Brennan L, et al. Long-term outcomes after bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of weight loss at 10 or more years for all bariatric procedures and a single-centre review of 20-year outcomes after adjustable gastric banding. Obes Surg. 2019;29:3–14.

- Courcoulas AP, Christian NJ, Belle SH, et al. Weight change andhealth outcomes at 3 years after bariatric surgery among individuals with severe obesity. JAMA. 2013;310:2416–2425.

- Shen R, Dugay G, Rajaram K, et al. Impact of patient follow-up on weight loss after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2004;14:514–519.

- Furbetta N, Gragnani F, Flauti G, et al. Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding on 3566 patients up to 20-year follow-up: Long-term results of a standardized technique. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2019:15:409–416.

- Halm U, Grothoff M, Lamberts R. Gastric balloon causing small bowel obstruction: treatment by double-balloon enteroscopy. Endoscopy. 2013;45:E78

- The FDA alerts health care providers about potential risks with liquid-filled intragastric balloons. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/letters-health-care-providers/fda-alerts-health-care-providers-about-potential-risks-liquid-filled-intragastric-balloons. Accessed October 14, 2019

Category: Past Articles, Review