Surgical Management of Complications after Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass

by Julietta Chang, MD, and Edward Felix, MD, FACS, FASMBS

by Julietta Chang, MD, and Edward Felix, MD, FACS, FASMBS

Drs. Chang and Felix are with the Weight Loss Surgical Institute of the Central Coast, Marian Regional Medical Center, A Dignity Hospital, in Santa Maria, California.

FUNDING: No funding was provided.

DISCLOSURES: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

ABSTRACT: This article is about recognizing when complications of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) occur and expediting their diagnosis and treatment, which can improve the outcome for the bariatric patient.

KEYWORDS: Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, complications, ulceration, stricture, reflux, fistula

Bariatric Times. 2020;17(5):9–10

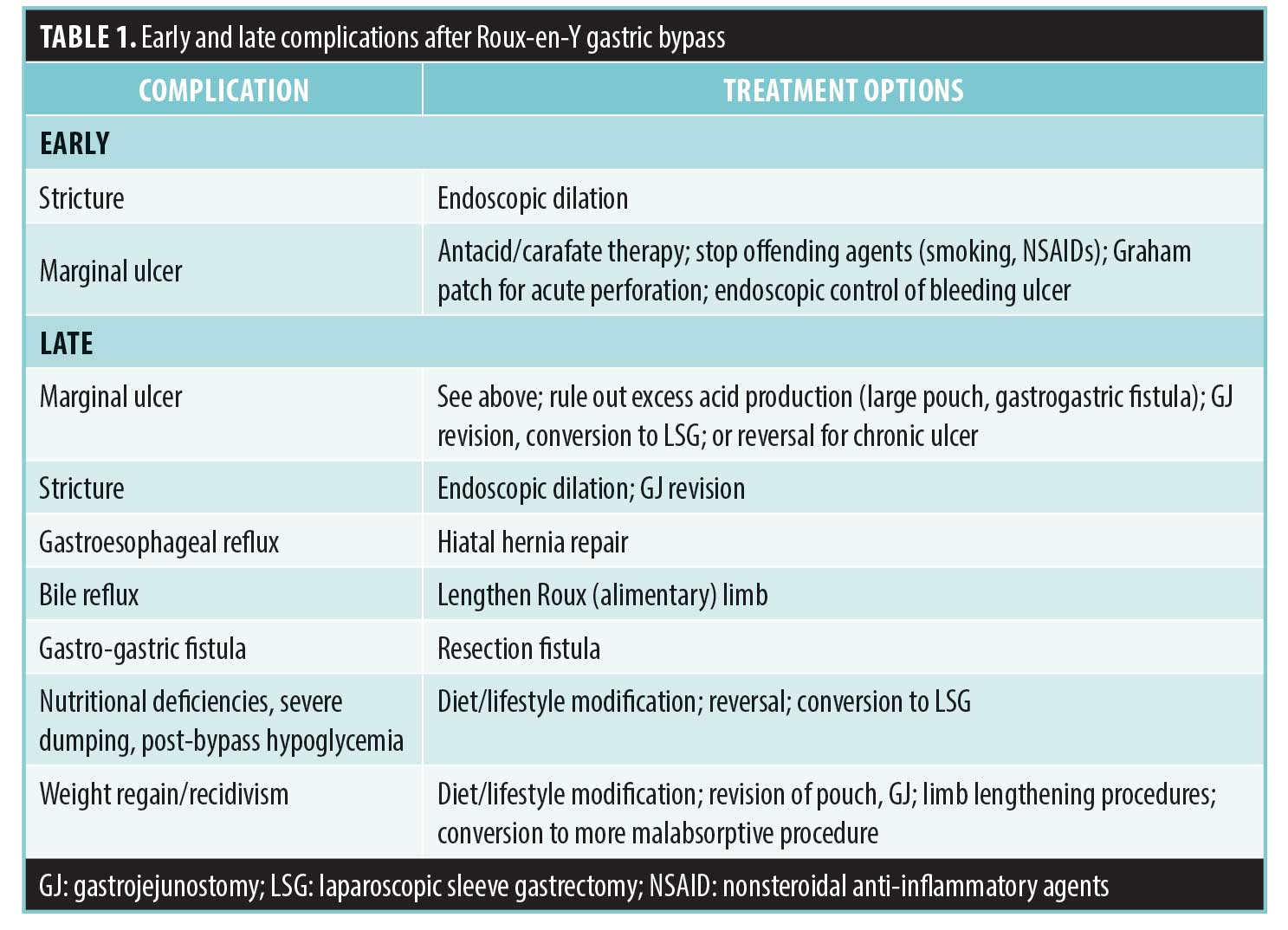

Over 200,000 patients in the United States were treated with bariatric surgery in 2017, and, of those patients, almost 18 percent underwent Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB).1 Though the safety and effectiveness of RYGB as a treatment for obesity are well-known, postoperative complications can still occur. Complications after gastric bypass can be divided into perioperative complications (within 72 hours); early (within first 3 months); or late (Table 1). This article addresses complications that could require surgical intervention or revisions, including ulceration, anastomotic strictures, gastroesophageal reflux, metabolic complications, and inadequate weight loss or weight gain.

Ulceration

Ulceration at the gastrojejunostomy can occur early or late after gastric bypass. Ulceration of the gastric pouch (stomal ulcers) is ischemic in nature and occurs early, while ulceration of the jejunum (marginal ulcers) is secondary to exposure of the small bowel to acid.2 The presence of foreign material, such as permanent suture or staples, can precipitate or prolong healing of ulcers. The use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and tobacco are known risk factors for the development of marginal ulcers at any point postoperatively. Later, excess acid production can play a role in recurrent or persistent ulcers, and a large pouch or the presence of a gastro-gastric fistula should be ruled out.

Patients with marginal ulcers present with epigastric pain, nausea, and vomiting. Upper endoscopy is diagnostic. First-line therapy is antacid therapy with a proton-pump inhibitor or H2 blockers and carafate with cessation of known inciting factors. If foreign bodies, such as intraluminal sutures, are seen during endoscopy, these should be gently removed. Endoscopy should be repeated in 8 to 12 weeks to document healing of the ulcer. As long as the patient has no risk factors for ulcer development (e.g., is not a smoker), antacid therapy can be tapered at this point. Patients with recurrent or persistent ulceration on maximal medical therapy need surgical revision of their gastrojejunostomy. Those with nonmodifiable risk factors (e.g., smokers or those requiring NSAID therapy for arthritis) should strongly consider either conversion to a sleeve gastrectomy (SG)3 or reversal to normal anatomy. Some patients present with acute perforation with the sudden onset of epigastric pain, and radiographic studies reveal free air. Treatment is laparoscopic patch repair of the perforation. If the perforation is extremely large, it can be converted to a gastrostomy with a Foley catheter or T-tube.4 Marginal ulcers might also bleed, and patients will present with acute or chronic blood loss. Endoscopy is both diagnostic and therapeutic, and the patient should be started on medical management concurrently, as detailed above.

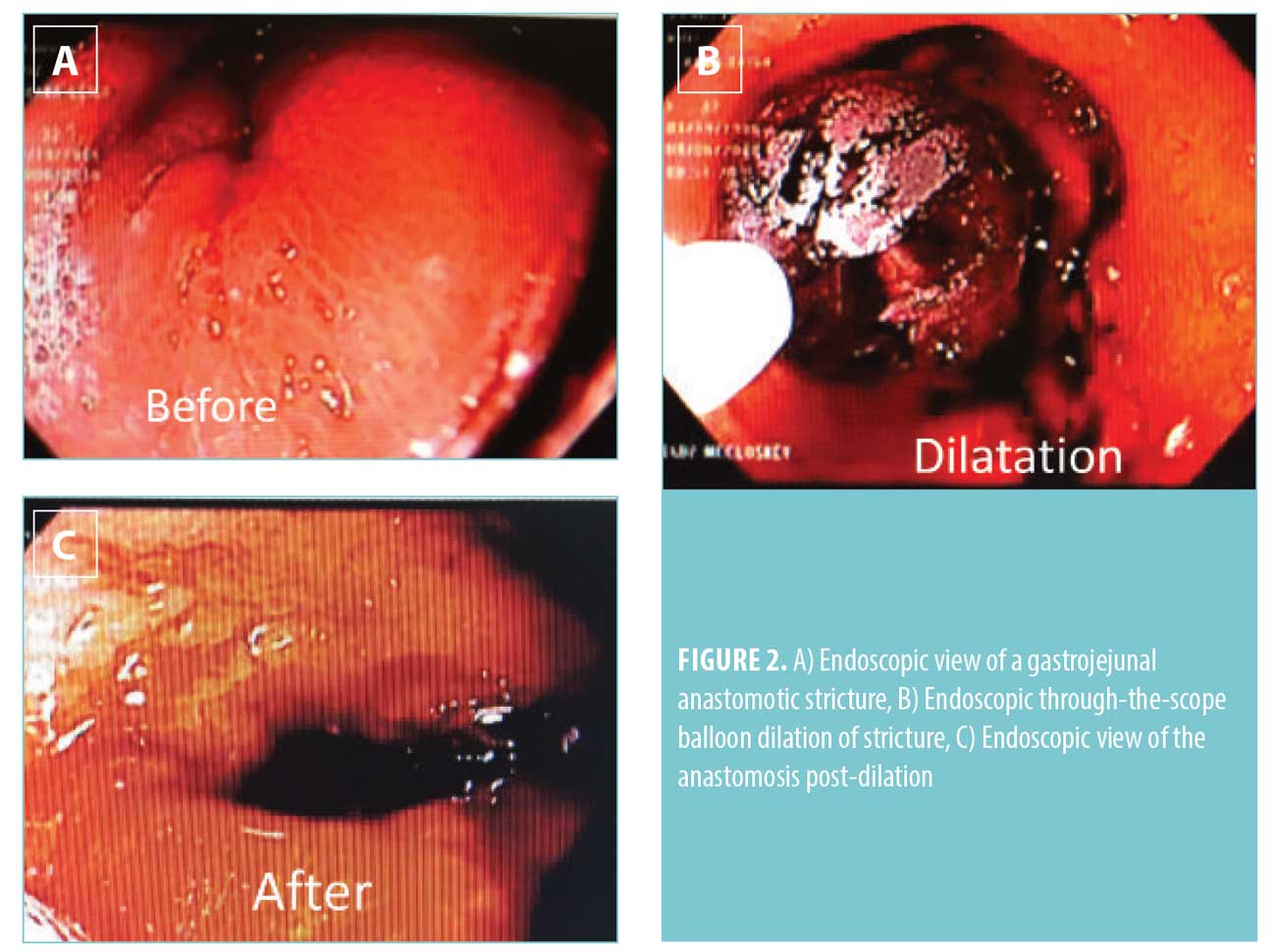

Anastomotic Strictures

Anastomotic strictures occur at the gastrojejunostomy and are one of the most common complications after bypass.5 Early strictures are generally technical, and the use of the 21mm end-to-end anastomosis (EEA) stapler has been associated with the highest incidence of strictures.6 Late strictures can form due to chronic ischemia from NSAID use or smoking, or from scarring as sequelae of marginal ulcers. The reported incidence of anastomotic strictures varies widely in the literature from 1.4 to 23.0 percent.7 Patients with strictures usually present with dysphagia to solid food within the first 3 to 6 weeks after RYGB. Endoscopy is both diagnostic and therapeutic. The stricture can be endoscopically dilated at the time of diagnosis. Repeat dilatation might be required for recurrent strictures.5 If a stricture occurs in the setting of an ulcer, concomitant ulcer therapy should be initiated as well. Recalcitrant strictures might require surgical revision of the gastrojejunostomy, but this is relatively rare, and most patients respond to endoscopic therapy alone.8

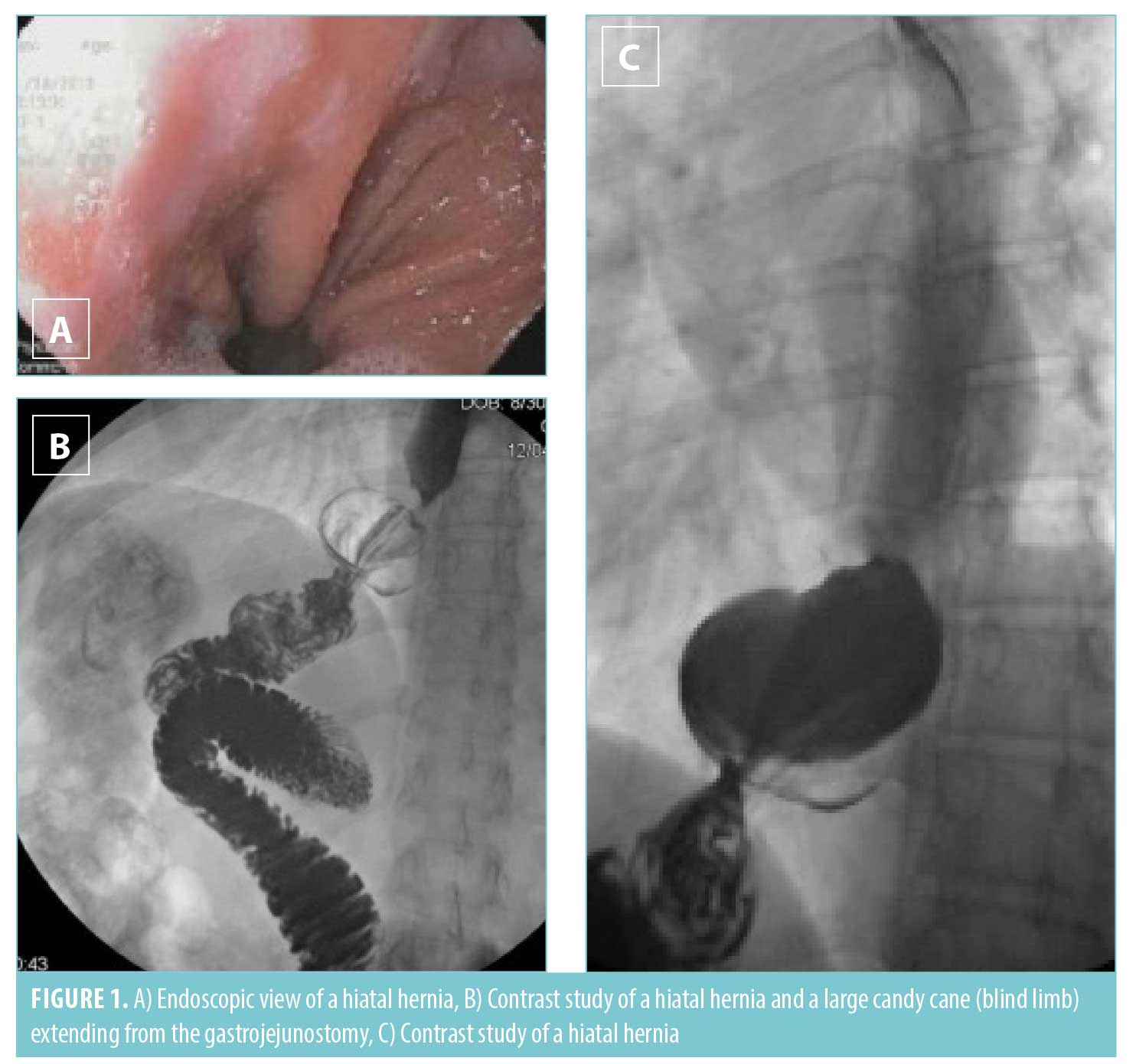

Gastroesophageal Reflux

Gastroesophageal reflux is usually a late complication due to an unrecognized hiatal hernia at the time of the index operation. With significant weight loss, fat at the gastroesophageal junction decreases, and the hiatus becomes more patulous, allowing the pouch to slip into the chest. Herniation of the pouch can also cause progressive outlet obstruction. Patients present with prandial epigastric pain and might present with weight loss if obstructive. Diagnosis is made on endoscopy or upper gastrointestinal series, and treatment is hiatal hernia repair. If acid reflux due to an enlarged pouch is a component of the patient’s constellation of symptoms, concomitant revision of the pouch at the time of hiatal repair should be considered.

Bile Reflux

Bile reflux is a rare cause of chronic epigastric pain, and the diagnosis should be considered if workup for other causes of pain is negative. The patient presents with epigastric pain and heartburn symptoms. Upper endoscopy reveals pouchitis and might reveal frank bile in the gastric pouch.9 A hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid (HIDA) scan is also diagnostic, which reveals retrograde reflux of bile up the Roux limb. The etiology is a short Roux limb; this could have been fashioned too short at the index operation or intestinal shortening. Treatment is surgery to lengthen the alimentary Roux limb.

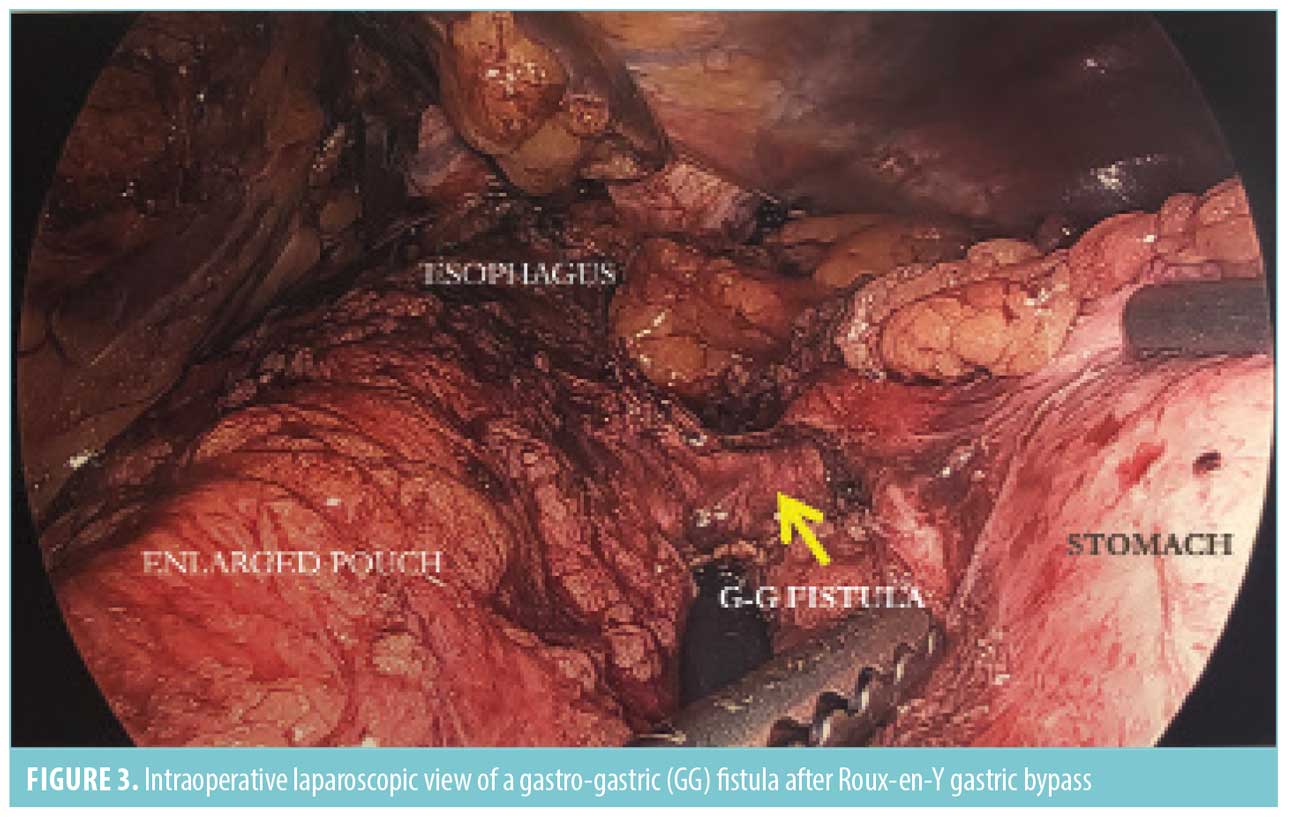

Gastro-gastric Fistulas

Gastro-gastric fistulas are abnormal connections between the gastric pouch and the bypassed remnant stomach. Due to increased acidic secretions from the bypassed stomach, this can lead to recurrent or refractory nonhealing ulcers. Large fistulous connections can cause weight regain by eliminating restriction and gastrointestinal neurohormonal changes that help maintain weight loss. Gastro-gastric fistulas were more common in the era of open RYGB with undivided gastric pouches. Incomplete transection at the gastroesophageal junction or anastomotic leak draining into the remnant stomach are causes of fistulas in the era of laparoscopic surgery. Fistulas are usually small and might be difficult to visualize on endoscopy, although the presence of bile in the gastric pouch should raise suspicion for a fistula. An upper gastrointestinal contrast study is the most sensitive study, which reveals prompt passage of contrast into the bypassed stomach prior to filling of the duodenum.10 Management of fistulas includes resection of the fistula, which might involve the gastro-jejunal anastomosis and thus involves revision of the gastrojejunostomy, as well as partial gastrectomy of the remnant stomach.

Metabolic Complications

Rare metabolic derangements include vitamin and mineral deficiencies, such as hypocalcemia, refractory hypoglycemia, and malnutrition. Patients might also have severe intolerance to their new bypass anatomy (i.e., dumping syndrome). First-line therapy is diet modification that involves increasing protein intake and avoidance of simple carbohydrates for hypoglycemia and dumping syndrome, and vitamin and mineral supplementation for associated deficiencies. However, patients might go on to require revisional surgery to a nonmalabsorptive anatomy, such as SG, or a reversal to normal anatomy.7,11 Pancreatic resection is no longer recommended.12 If an islet cell tumor is found on a computed tomography (CT) scan, it should be appropriately treated, but this is extremely rare event.

Inadequate Weight Loss or Regain

Inadequate weight loss or regain is seen in 10 to 20 percent of RYGB patients.13 The etiology can be anatomic, such as an enlarged pouch or a dilated gastrojejunostomy or a gastro-gastric fistula, or it can be due to patient-related factors, such as poor eating habits and sedentary lifestyle. Diet and lifestyle changes are addressed first. Medical therapy with prescription medications may be appropriate as well.14 Endoscopy and upper gastrointestinal series should be obtained to query the patient’s anatomy. If an enlarged pouch or patulous gastrojejunostomy is present, these potentially can be revised surgically. Although endoscopic revision of both pouch and stomal size are reported, the durability of these interventions is controversial.15 Surgical revision with distalization of the jejunojejunostomy or conversion to another more malabsorptive procedure, such as duodenal switch, are other alternatives for weight regain, recidivism, or the recurrence of a comorbid disease.7

Conclusion

In conclusion, RYGB remains a popular bariatric procedure for its known significant and durable weight loss with resolution of comorbid diseases. However, complications can occur at any point for years after surgery, and the surgeon must remain vigilant regarding the potential issues that might arise with a patient’s postbypass anatomy to address complications appropriately.

References

- Estimate of Bariatric Surgery Numbers, 2011-2017 | American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. June 2018. https://asmbs.org/resources/estimate-of-bariatric-surgery-numbers. Accessed July 31, 2018.

- Kane ED, Romanelli JR. Complications of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. SAGES Manual of Bariatric Surgery, Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2018, p. 403–429.

- Felix EL, Swartz DE. Conversion of laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Am J Surg. 2003;186:648–651.

- Felix EL, Kettelle J, Mobley E, Swartz D. Perforated marginal ulcers after laparoscopic gastric bypass. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:2128–2132.

- Carrodeguas L, Szomstein S, Zundel N, et al. Gastrojejunal anastomotic strictures following laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery: analysis of 1291 patients. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2006;2:92–97.

- Takata MC, Ciovica R, Cello JP, et al. Predictors, treatment, and outcomes of gastrojejunostomy stricture after gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Obes Surg. 2007;17:878–884.

- Brethauer SA, Kothari S, Sudan R, et al. Systematic review on reoperative bariatric surgery: American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Revision Task Force. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10:952–972.

- Swartz DE, Gonzalez V, Felix EL. Anastomotic stenosis after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a rational approach to treatment. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2006;2:632–636; discussion 637.

- Swartz DE, Mobley E, Felix EL. Bile reflux after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: an unrecognized cause of postoperative pain. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2009;5:27–30.

- Carrodeguas L, Szomstein S, Soto F, et al. Management of gastrogastric fistulas after divided Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery for morbid obesity: analysis of 1,292 consecutive patients and review of literature. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2005;1:467–474.

- Switzer NJ, Karmali S, Gill RS, Sherman V. Revisional bariatric surgery. Surg Clin North Am. 2016;96:827–842.

- Salehi M, Vella A, McLaughlin T, Patti ME. Hypoglycemia after gastric bypass surgery: current concepts and controversies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103(8):2815–2826.

- Tran DD, Nwokeabia ID, Purnell S, et al. Revision of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for weight regain: a systematic review of techniques and outcomes. Obes Surg. 2016;26:1627–1634.

- Stanford FC, Alfaris N, Gomez G, et al. The utility of weight loss medications after bariatric surgery for weight regain or inadequate weight loss: a multi-center study. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13:491–500.

- Gall AS, DuCoin CG, Berducci MA et al. Endoscopic revision of gastric bypass: holy grail or epic fail? Surg Endosc. 2016;30(9):3922–3927.

Category: Past Articles, Review