The Prevalence of Musculoskeletal Injuries in Bariatric Surgeons

by Salman Al-Sabah, MD, MBA, FRSC, FACS; Eliana Al Haddad, ND; and Haris Khwaja, MD

by Salman Al-Sabah, MD, MBA, FRSC, FACS; Eliana Al Haddad, ND; and Haris Khwaja, MD

Drs. Al-Sabah, Al Haddad, and Khwaja are with the Al-Amiri Hospital in Kuwait.

Funding: No funding was provided for this article.

Disclosures: The authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Abstract: Background. As the popularity of bariatric surgery increases, efforts into improving its patient safety and decreasing its invasiveness have also been on the rise. However, with this shift toward minimal invasiveness, surgeon ergonomic constraints have been imposed, with a recent report showing a 73- to 88-percent prevalence of physical complaints in surgeons performing laparoscopic surgeries.

Methods. A web-based survey was designed and sent out to bariatric surgeons around the world. Participants were queried about professional background, primary practice setting, and various issues related to bariatric surgeries and musculoskeletal (MSK) injuries.

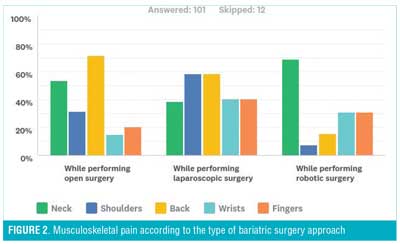

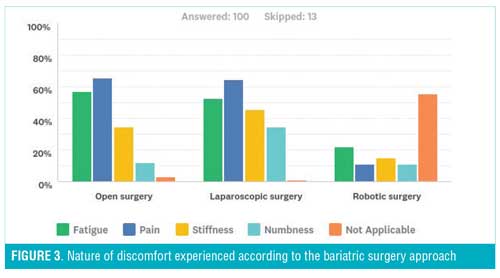

Results. There were 113 responses from surgeons from 34 countries around the world. Of the responses, 66 percent reported that they experienced discomfort/pain attributed to surgical reasons, causing their case load to decrease in 27.2 percent of the surgeons. The back was the most affected area in those performing open surgery, while shoulders and back were equally as affected in those performing laparoscopic surgery. For those performing robotic surgery, the neck was the most affected area, with 29.4 percent of the surgeons reporting that this pain affected their task accuracy/surgical performance. A higher percentage of female surgeons reported pain in the neck, back, and shoulder area when performing laparoscopic procedures. Supine positioning of patients evoked more discomfort in the wrists, while the French position caused more discomfort in the back region. Only 57.7 percent sought medical treatment for their MSK problem, of which 6.35 percent had to undergo surgery for their issue—55.6 percent of those felt that the treatment resolved their problem.

Conclusion. MSK injuries and pain are a common occurrence among the population of bariatric surgeons (66%) and has the ability to hinder performance at work. Therefore, it is important to investigate ways to improve ergonomics for these surgeons to improve quality of life.

Keywords: Musculoskeletal injuries, bariatric, surgery, laparoscopic, surgeons

Bariatric Times. 2018;15(3):16–19.

Introduction

Surgeons are known to be a unique group of healthcare professionals that are at a higher risk for the development of a range of work-related musculoskeletal (MSK) pains and injuries. MSK disorders are typically defined as musculoskeletal complaints, symptoms, or pain that reflect a number of conditions, such as neck pain, back pain, shoulder pain, limb pain, carpal tunnel syndrome, myofacial dysfunction syndrome, atypical facial pain, and so forth.1 These could range from mild, infrequent symptoms, to severe and debilitating ones,2 interfering with surgeons’ daily activities.

As the popularity of bariatric surgery increases,3 efforts into improving its patient safety and decreasing its invasiveness have also been on the rise. However, with this shift toward minimal invasiveness, surgeon ergonomic constraints have been imposed, with recent reports showing a 73- to 88-percent prevalence of physical complaints in surgeons performing laparoscopic surgeries.4–6 And while newer techniques in minimally invasive surgeries, such as natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) and single-incision laparoscopic surgery (SILS), have greater benefits for the patient,7,8 they have been shown to increase the physical workload for the surgeon.9–11 On the other hand, the recent emergence of robotic surgery might provide the surgeon with ergonomic benefits, allowing the surgeon to operate from a seated position, with more degrees of freedom for instrumental movement and three-dimensional vision.12,13

Therefore, the physical posture of a bariatric surgeon while providing care to their patients ideally should be that all muscles are in a relaxed, well-balanced, and neutral position. Postures outside of this neutral position for a prolonged period, such as those experienced during surgery, are likely what cause the musculoskeletal discomfort experienced by this population of physicians.14

We therefore conducted a study to explore the prevalence of MSK pain and injuries in bariatric surgeons from around the world, investigating possible factors contributing to these injuries.

Materials and Methods

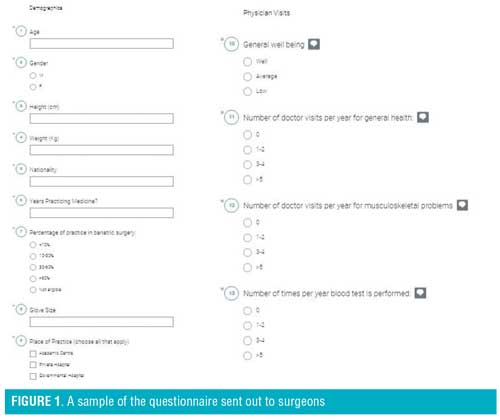

Survey. We developed an online, web-based survey adapted from the previously validated Nordic Musculoskeletal Questionnaire15 using an online survey generator. Figure 1 shows a sample of the questionnaire. The survey was then sent out to bariatric surgeons around the world through multiple social media platforms. Participants were queried about professional background and demographics, primary practice setting, and various issues related to bariatric surgeries and MSK injuries. Demographics collected included sex, age, height, weight, years practicing, average hours in the operating room per week, glove size, and most commonly employed operating position.

The sections of the survey included demographics, physician visits, bariatric surgery background data, bariatric procedures, revisional bariatric procedures, and discomfort and procedure duration. The symptom portion of the questionnaire inquired about the nine different anatomic regions used in the NMQ: neck, shoulders, elbows, wrists/hands, upper back, lower back, hips/thighs, knees, and ankles/feet. The survey skipped to the next section if a respondent indicated no pain experienced in any body region. If they answered positively, however, further questions followed. These included questions about interference with work, difficulties, and characterization of the difficulty (pain, stiffness, weakness, paresthesia, or other), severity (scale of 0–10), whether the symptoms stopped the surgeon from operating, and whether the surgeon attributed their symptoms to their work.

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Statistical analysis. The study was conducted anonymously between May 2017 and August 2017, receiving responses from 113 bariatric surgeons from around the world. Descriptive statistics were analyzed using SPSS software version 22. The significance of the difference between the two values was analyzed using a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test. Significant levels were assessed at p-value <0.05.

Results

A total of 113 bariatric surgeons from 34 countries completed the survey during the period of data collection, with the majority (15.9%) being from Kuwait. Of the respondents, 94.7 percent were men, with an average age of 45.2 years. The rest of the demographics are summarized in Table 1. Details on respondents’ health status are reported in Table 2.

Table 3 summarizes the experiences of the surgeons in open, laparoscopic, and robotic surgery. It was seen that the bariatric surgeries performed were mostly sleeve gastrecotmies (98.2%) and gastric bypasses (88%), with 65.7 percent performing the surgery in the French position (Table 4, Table 5).

Sixty-six percent of participants reported that they have experienced some level of discomfort/pain attributed to surgical reasons, causing the case load to decrease in 27.2 percent of the surgeons (Table 6). It was seen that the back was the most affected area in those performing open surgery, while shoulders and back were equally as affected in those performing laparoscopic, and the neck for those performing robotic (Figure 2), with 29.4 percent of the surgeons reporting that this pain has affected their task accuracy/surgical performance. As demonstrated by Figure 3, the nature of the discomfort experienced was shown to be mostly pain from performing open and laparoscopic surgery, but of the fatigue nature for robotic surgery. Table 6 illustrates the difference between the sexes when it came to assessing the location of pain according to the type of surgery. A higher percentage of female surgeons than male surgeons reported pain in the neck, back, and shoulder areas when performing laparoscopic procedures. Supine positioning of patients evoked more discomfort in the wrists, while the French position caused more discomfort in the back region. An interesting observation was seen when correlating amount of physical exercise per week with pain/discomfort during surgery. It was seen that a higher percentage of surgeons that did not exercise experienced more issues in the neck and back region, while those that exercised more than three hours a week experienced issues in their shoulders and wrists in both open and laparoscopic approaches (Table 7).

Only 36.9 percent of the respondents who had experienced pain/discomfort due to performing surgeries had some form of imaging done to diagnose the problem (Table 8) and 57.7 percent sought medical treatment for their MSK problem, of which 6.35 percent had to undergo surgery for their issue—55.6 percent of those felt that the treatment resolved their problem.

Discussion

Work-related MSK injuries are one of the most important occupational health issues among healthcare workers, and with the high physical demands of surgeons’ daily activities, high rates of MSK injuries have been reported, specifically between the orthopedic surgery group.16–18 This has been hypothesized to be due to the necessity of maintaining a static posture for long periods of time while using precision hand and wrist movements during surgical procedures.14 In a systemic review conducted, Alleblas et al19 was able to show that the prevalence of MSK complaints was 74 percent among surgeons. This number is comparable to our percentage of bariatric surgeons that had reported the existence of some form of MSK problem that they would attribute to their work. However, there are currently no studies that look specifically into the prevalence and cause of MSK injuries and pain the bariatric surgery group.

A possible angle to consider is that, while the prevalence of bariatric surgery is on the rise,3 the shift toward the laparoscopic approach has become more prominent, with 68.5 percent of our study population having over 10 years of experience in laparoscopic bariatric surgery as of 2017. This has been hypothesized to be due to the preference for laparoscopic bariatric surgeries among patients, as well as this being the most recommended approach by guidelines, given the lower complication rates and improved aesthetics over the open approach.20–22 However, this comes with its own consequences given a different form of physical demand and physical workload for the surgeon, taking little consideration of ergonomics. As shown by our study, 58.4 percent of bariatric surgeons complained of pain in their shoulders, as well as in the back region and 40.59 percent reported having pain in their wrists and fingers while performing laparoscopic bariatric surgeries. These numbers were shown to be notably higher than those for the open approach, with 15.2 percent and 20.7 percent reporting pain in their wrists and fingers, respectively. This observation is understandable given the equipment and surgical techniques employed in laparoscopic bariatric surgeries.

One reported benefit from the introduction of robotic surgery in bariatrics is the superior ergonomics that it is known to offer. However, from our study population, it was shown that 69.2 percent of the surgeons complained of having had some form of pain or discomfort in the neck that they attributed to performing bariatric surgery using the robotic approach. This can be explained given the position in which robotic surgery is performed. This has also been shown to be the case in several studies,4,23–25 but at a much lower average prevalence of 35 percent than in our study population.

An interesting observation noted was the difference in results when comparing sexes. On average, female surgeons are known to have smaller hands and glove sizes, and therefore the “one size fits all” of the laparoscopic equipment handles might be a cause of discomfort.4,9 However, according to our results, male participants tended to exhibit more pain during laparoscopic bariatric procedures in their wrists and fingers compared to female participants (17.6% and 18.0% vs. 11.8% and 5.9%, respectively), but vice versa when it came to neck and shoulder complaints (15.8% and 23.9% vs. 23.5% and 35.3%, respectively). This finding could be influenced by the anatomical muscular differences between the sexes, as well as the differences between working life and private circumstances.26

Physical complains might be thought of as “part of the job;” however, when such complaints appear to influence the quality of surgical care, it becomes a matter of concern. As was shown by our study, 27.2 percent of the surgeons felt that the pain they had experienced had caused them to decrease their caseload, with 29.4 percent of the surgeons reporting that this pain affected their task accuracy/surgical performance. Multiple studies illustrated the same finding, with surgeons believing that their surgical performance was negatively affected by their own injury or pain.27–29 This observation is of concern and raises the question as to what should be done to decrease these modifiable factors.

The limitations of our study include the use of self-reported measures to assess the degree of pain, as well as recall bias, as the disorders were surgeon-reported injuries. However, while subjective reports are not alone diagnostic of musculoskeletal pathology, subjective complaints remain the most common manifestation of musculoskeletal occupational injury.

Conclusion

MSK injuries and pain are a common occurrence among the population of bariatric surgeons, and have the ability to hinder performance at work, decreasing case loads and performance. Therefore, it is important to investigate ways to improve ergonomics for these surgeons to improve quality of life. From our results, we could see that the French position was a cause of back pain, while lack of exercise was correlated to neck and back issues.

References

- Karahan A, Kav S, Abbasoglu A, Dogan N. Low back pain: prevalence and associated risk factors among hospital staff. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65:516–24.

- United States: Department of labour; 2005. Labour statistics Workplace injuries and illnesses in 2005.

- “Estimate of Bariatric Surgery Numbers, 2011-2015.” American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. N.p., n.d. Web. 01 Aug. 2017.

- Franasiak J, Ko EM, Kidd J, et al. Physical strain and urgent need for ergonomic training among gynecologic oncologists who perform minimally invasive surgery. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;126:437–442.

- Park A, Lee G, Seagull FJ, et al. Patients benefit while surgeons suffer: an impending epidemic. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210:306–313.

- Sari V, Nieboer TE, Vierhout ME, et al. The operation room as a hostile environment for surgeons: physical complaints during and after laparoscopy. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2010;19:105–109.

- Sodergren MH, Aslanyan A, McGregor CG, et al. Pain, well-being, body image and cosmesis: a comparison of single-port and four-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2014;23:223–229.

- Autorino R, Stein RJ, Lima E, et al. Current status and future perspectives in laparoendoscopic single-site and natural orifice transluminal endoscopic urological surgery. Int J Urol. 2010;17:410–431.

- Lee G, Sutton E, Clanton T, et al. Higher physical workload risks with NOTES versus laparoscopy: a quantitative ergonomic assessment. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:1585–1593.

- Alleblas CC, Velthuis S, Nieboer TE, et al. The physical workload of surgeons: a comparison of SILS and conventional laparoscopy. Surg Innov. 2015;22:376–381.

- Koca D, Yildiz S, Soyupek F, et al. Physical and mental workload in singleincision laparoscopic surgery and conventional laparoscopy. Surg Innov. 2015;22:294–302.

- Zihni AM, Ohu I, Cavallo JA, et al. Ergonomic analysis of robot-assisted and traditional laparoscopic procedures. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:3379–3384.

- Lawson EH, Curet MJ, Sanchez BR, et al. Postural ergonomics during robotic and laparoscopic gastric bypass surgery: a pilot project. J Robot Surg. 2007;1:61–67.

- Luxembourg: European Communities; 2004. European Communities Work and health in the EU, a statistical portrait.

- Kuorinka I, Jonsson B, Kilbom A, et al. Standardised Nordic questionnaires for the analysis of musculoskeletal symptoms. Appl Ergon. 1987;18(3):233–237

- Lester JD, Hsu S, Ahmad CS. Occupational hazards facing orthopedic surgeons. Am J Orthop. 2012;41(3):132–139.

- Mirbod SM, Yoshida H, Miyamoto K, et al. Subjective complaints in orthopedists and general surgeons. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 1995;67(3):179–186.

- Auerbach JD, Weidner ZD, Milby AH, et al. Musculoskeletal disorders among spine surgeons: results of a survey of the Scoliosis Research Society membership. Spine. 2011;36(26):1715–1721.

- Alleblas, Chantal C. J., Anne Marie De Man, Lukas Van Den Haak, Mark E. Vierhout, Frank Willem Jansen, and Theodoor E. Nieboer. “Prevalence of Musculoskeletal Disorders Among Surgeons Performing Minimally Invasive Surgery.” Annals of Surgery (2017): 1. Web.

- Kolfschoten NE, van Leersum NJ, Gooiker GA, et al. Successful and safe introduction of laparoscopic colorectal cancer surgery in Dutch hospitals. Ann Surg. 2013;257:916–921.

- Keus F, de Jong JA, Gooszen HG, et al. Laparoscopic versus open cholecystectomy for patients with symptomatic cholecystolithiasis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;4:CD006231.

- Sauerland S, Jaschinski T, Neugebauer EA. Laparoscopic versus open surgery for suspected appendicitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;10:CD001546.

- Plerhoples TA, Hernandez-Boussard T, Wren SM. The aching surgeon: a survey of physical discomfort and symptoms following open, laparoscopic and robotic surgery. J Robot Surg. 2012;6:65–72.

- Santos-Carreras L, Hagen M, Gassert R, et al. Survey on surgical instrument handle design: ergonomics and acceptance. Surg Innov. 2012;19:50–59.

- Giberti C, Gallo F, Francini L, et al. Musculoskeletal disorders among robotic surgeons: a questionnaire analysis. Arch Ital Urol Androl. 2014;86:95–98.

- Krantz G, Berntsson L, Lundberg U. Total workload, work stress and perceived symptoms in Swedish male and female white-collar employees. Eur J Public Health. 2005;15:209–214.

- Adams SR, Hacker MR, McKinney JL, et al. Musculoskeletal pain in gynecologic surgeons. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013;20: 656–660.

- Ruitenburg MM, Frings-Dresen MH, Sluiter JK. Physical job demands and related health complaints among surgeons. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2013;86:271–279.

- Esposito C, Najmaldin A, Schier F, et al. Work-related upper limb musculoskeletal disorders in pediatric minimally invasive surgery: a multicentric survey comparing laparoscopic and sils ergonomy. Pediatr Surg Int. 2014;30:395–399.

Category: Original Research, Past Articles