Operating Room Set-up for Patients with Class III Obesity Who Undergo a Cesarean Section

by Rachelle Shirley, MD, DM(OG), FACOG; Rachel Hamilton, BKin, BScN; Kim Ngo, BScN; Catherine Agnotti, RN, BScN, MN; and Cynthia Maxwell, MD, FRCSC, DABOM

Dr. Shirley is Clinical Fellow-Pregnancy Obesity Medicine and Surgery, Maternal Fetal Medicine Division, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Sinai Health, University of Toronto in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Ms. Hamilton is Clinical and Systems Flow Facilitator, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Sinai Health in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Ms. Ngo is Nursing Clinical Coordinator, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Sinai Health in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Ms. Angotti is Clinical Nurse Specialist, Mount Sinai Hospital in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Dr. Maxwell is with the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Sinai Health, University of Toronto in Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Funding: No funding was provided for this article.

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Bariatric Times. 2023;20(2):16–20.

Abstract

Pregnant patients with Class III obesity are at an increased risk of perinatal morbidity and mortality, as well as delivering by cesarean section. It has been postulated that the risk of caesarean section within this group is increased due to dysfunctional labour resulting from excess adipose tissue in the maternal pelvis which narrows the birth canal, failure to progress in the first or second stage of labor, and decreased responsiveness to oxytocin. There is even a higher risk of antepartum and intrapartum stillbirth among this population of patients. Whether patients with Class III obesity are to be routinely offered a cesarean section or may be allowed a trial of labor is still debatable. Preoperative planning with a multidisciplinary team is the first important step in ensuring safety. For the purpose of this article, we endeavor to discuss the ideal operating room setup for patients with Class III obesity who undergo cesarean delivery to allow for safety and efficiency.

Keywords: Obesity, class III obesity, pregnancy, delivery, cesarean section, operating room, OR

Pregnant patients with Class III obesity are at an increased risk of perinatal morbidity and mortality.1 This risk is increased due to numerous factors related to the effect of obesity on pregnancy and its associated physiological changes, and the effect of the pregnancy on obesity.

Pregnant patients with Class III obesity are at an increased risk of delivering by cesarean section. There is a three-fold risk of cesarean section in patients with severe obesity compared to those of normal weight.2,3 The risk of patients with obesity undergoing an emergency cesarean section was two-fold based on a systematic review and meta-analysis.3 It has been postulated that the risk of cesarean section within this group is increased due to dysfunctional labor resulting from excess adipose tissue in the maternal pelvis which narrows the birth canal, failure to progress in the first or second stage of labor, and decreased responsiveness to oxytocin.2 Maternal obesity is also associated with fetal macrosomia, intrapartum fetal distress and cord accidents, which all might influence the decision for performing a cesarean section.2 Maternal obesity increases the risk of medical disorders of pregnancy, such as gestational diabetes, which increases the risk of perinatal morbidity and cesarean section.2 There is even a higher risk of antepartum and intrapartum stillbirth among this population of patients.2,4,5

Whether patients with Class III obesity are to be routinely offered a cesarean section or may be allowed a trial of labor is still debatable.6 This can be due to the vast interindividual variability in body mass index (BMI) and body fat distribution and their effects on the pregnancy. However, what we do know is the higher the BMI within this category, the higher the chance of cesarean section.1,2,5

Preoperative planning with a multidisciplinary team is the first important step in ensuring patient safety. For the purpose of this article, we endeavor to discuss the ideal operating room (OR) set-up for patients with Class III obesity who undergo cesarean delivery to allow for safety and efficiency.

With increasing trends in obesity worldwide and in Canada,7 it is useful to review the tools that would allow for safety in the OR at the time of cesarean section, as patients with Class III obesity are at higher risk for intraoperative complications. Pre- and postoperative strategies for safe outcomes at the time of cesarean section within this population have been well documented, but there are few reports of intraoperative strategies at the time of cesarean section for this population.

Completing a surgical safety checklist (i.e., the World Health Organization [WHO] Surgical Safety Checklist8) before induction of anesthesia, before the skin incision, and before the patient leaves the OR is advisable to ensure that the entire team is aware of important patient risk factors and concerns.

Operating Room Equipment

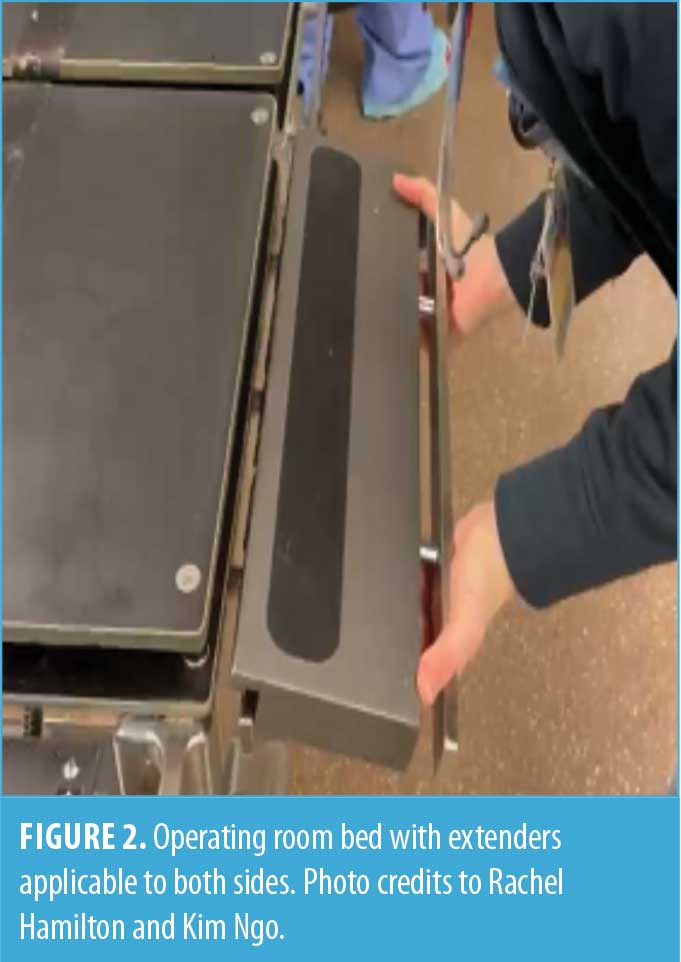

An OR bed that has the appropriate weight capacity and the ability for adding extenders on either side is suitable for these cases (Figures 1 and 2). The patient’s lower limbs can be secured with straps that are attached to the bed, and the team should consider special care of pressure areas.

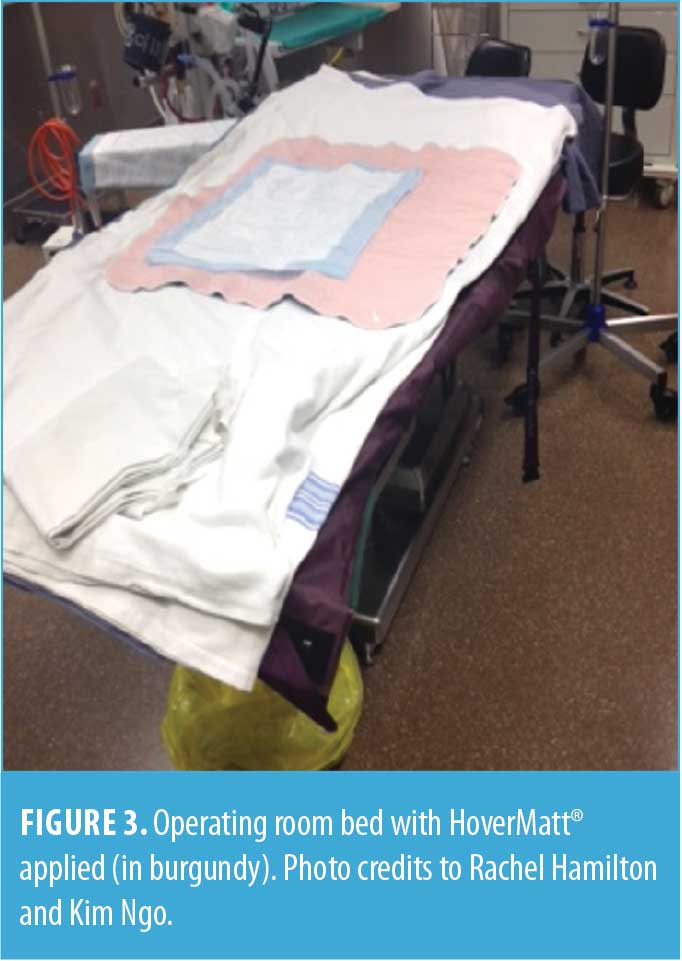

Application of an appropriate lateral transfer equipment, such as an air transfer system, (i.e ., Hover Matt® Air Transfer System, HoverTech International, Allentown, PA) allows ease of transfer of the patient (Figure 3). Appropriate positioning of the patient in the supine position prior to regional anesthesia can suit the ergonomics of the surgeons and reduce physical burden.

Anesthetic Considerations

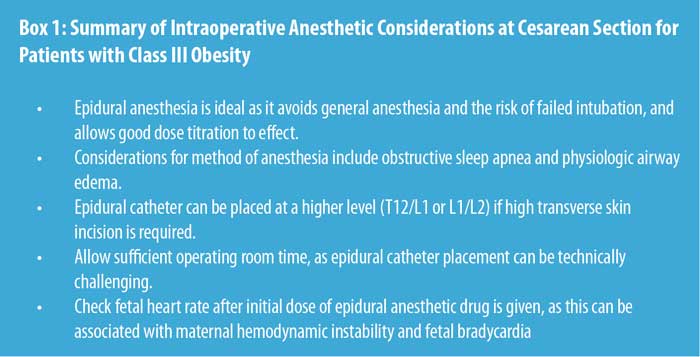

Preoperative assessment of the abdominal panniculus and the planned incision site should be discussed with the anesthesia team. Patients with Class III obesity might require a high transverse skin incision (supra- or subumbilical); therefore, the epidural catheter placement might be best suited at a higher level (i.e., at T12/L1 or L1/L2). Epidural anesthesia can be technically challenging in this population,9,10 and sufficient surgical time should be allowed for these cases to proceed successfully without pain for the patient. Pregnant patients with Class III obesity are likely to have physiologic airway edema, as well as obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), resulting in a difficult airway. Therefore, epidural is a safe option, as the need for airway management is avoided.10 It allows good dose titration to effect and sufficient pain management throughout the length of the surgery, while avoiding general anesthesia (GA), which is associated with failed endotracheal intubation and aspiration in this population.11 The anesthesiologist might choose to avoid use of sedative drugs due to risks associated with OSA, and therefore, it is important for the team to be aware of undue exposure of the patient and to use person-first language—as always—which is nonstigmatizing.

Due to the likelihood of maternal hemodynamic instability and subsequent fetal bradycardia when epidural anesthesia is initiated, the external fetal heart rate monitor may be used to assess the fetal heart rate. Other routine preoperative measures, such as urinary catheter insertion (while coordinating with the anesthesia team) and correct placement of diathermy grounding plate is expected. See Box 1 for a summary of anesthetic considerations.

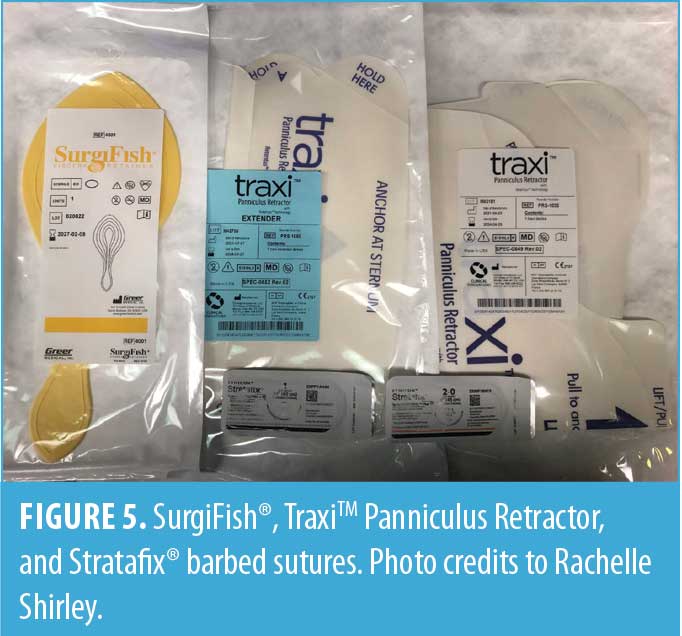

Abdominal preparation can be a two-step process depending on the size of the abdominal panniculus. Use of a panniculus retractor with or without extenders for patients who are candidates for pfannensteil incisions can reduce physical burden and improve the ergonomics of the surgeons (Figure 5). The clinical use and effectiveness of the panniculus retractor for patients with Class III obesity who undergo cesarean section is an area of research, and such studies are underway.12

Operating Instruments

The bariatric instruments (Figure 4, Table 1, Addendum A, and Figure 8) can aid abdominal entry, hysterotomy, uterine closure, abdominal closure, and skin closure. These instruments are similar to instruments used for a routine cesarean section, but they are larger and sturdier for the purpose of operating on thicker tissues. In addition to retractors listed in Table 1 and Addendum A, the use of a disposable, self-retaining, 360-degree circumferential retractor assists in retracting adipose tissue away from the area of focus (Figure 6). A latex-free thermoplastic visceral retainer can also be useful for retracting omentum and bowel, while closing the peritoneal cavity and abdominal fascia (Figure 5).

Sutures

With a high transverse skin incision and abdominal entry, the transverse incision on the uterus is likely to be higher than is typical within the lower uterine segment or even midcorpus. The myometrium is often thicker at this level, requiring double layer closure with a size 1 absorbable suture13 to achieve hemostasis in some cases. Peritoneal closure is optional and can be individualized. A size 1 delayed absorbable suture is typically used to close the anterior rectus sheath/fascia using a continuous technique.13,14 Use of a size 1 delayed absorbable barbed suture (Figure 5) provides uniform tensile strength throughout the length of fascial closure and avoids the need for knot tying and for an assistant to follow placement of the suture, thereby providing efficient fascial closure.15 These attributes can be applied in the closure of the rectus fascia in persons with Class III obesity, in whom there is a higher risk of wound infections, wound dehiscence, and incisional hernias.16 However, if the surgeon intends to close the fascia with a size 1 delayed absorbable barbed suture, then peritoneal closure might reduce the risk of visceral entanglement within the barbs and subsequent bowel complications.17

Ideally, the subcutaneous layer should be closed in equidistant layers with an appropriate monofilament absorbable suture to aid healing and reduce the risk of wound seroma formation and wound infection. A 2-0 barbed suture (Figure 4) can assist with this endeavor, as it stays in place and has uniform tensile strength. Skin closure with a 3-0 monofilament absorbable suture might also reduce the risk of wound infection in this population.

Application of a negative pressure dressing (Figure 7) to the closed wound for seven days postoperatively assists with decreasing hematoma and seroma formation and wound infection.18

Conclusion

Safe, efficient surgery for patients with Class III obesity undergoing a cesarean section requires having individualized care plans, multidisciplinary team coordination, and physical space and equipment planning. It will be interesting to see how contemporary modalities that assist with surgeons’ ergonomics, surgical efficiency, and patient safety evolve with further research and become integrated into routine intraoperative care of this population.

References

- Rogers AJG, Harper LM, Mari G. A conceptual framework for the impact of obesity on risk of cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219(4):356–363.

- Chu SY, Kim SY, Schmid CH, et al. Maternal obesity and risk of cesarean delivery: a meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2007;8(5):385–394.

- Poobalan AS, Aucott LS, Gurung T, et al. Obesity as an independent risk factor for elective and emergency caesarean delivery in nulliparous women—systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Obes Rev. 2009;10(1):28–35.

- Chu SY, Kim SY, Lau J, et al. Maternal obesity and risk of stillbirth: a metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197(3):223–228.

- Cedergren MI. Maternal morbid obesity and the risk of adverse pregnancy outcome. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(2):219–224.

- Machado LS. Cesarean section in morbidly obese parturients: practical implications and complications. N Am J Med Sci. 2012;4(1):13–18.

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Obesity in Canada – Snapshot. Public Health Agency of Canada; 2009.

- van Klei WA, Hoff RG, van Aarnhem EE, et al. Effects of the introduction of the WHO “Surgical Safety Checklist” on in-hospital mortality: a cohort study. Ann Surg. 2012;255(1):44–49.

- Bamgbade OA, Khalaf WM, Ajai O, et al. Obstetric anaesthesia outcome in obese and non-obese parturients undergoing caesarean delivery: an observational study. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2009;18(3):221–225.

- An X, Zhao Y, Zhang Y, et al. Risk assessment of morbidly obese parturient in cesarean section delivery: a prospective, cohort, single-center study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(42):e8265.

- Cho A, So J, Ko EY, Choi D. Spinal anesthesia for cesarean section in a super morbidly obese parturient: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(31):e21435.

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Traxi Panniculus Retractor for cesarean delivery. Updated 23 Aug 2021. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03651076. Accessed 1 Dec 2022.

- Cunningham, FG, Leveno, KJ, Bloom, SL, et al. Williams Obstetrics. 23rd ed. McGraw Hill Medical; 2010:553–555.

- Shand AW, Chen JS, Schnitzler M, Roberts CL. Incisional hernia repair after caesarean section: a population-based study. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2015;55(2):170–175.

- Agarwal S, D’Souza R, Ryu M, Maxwell C. Barbed vs conventional suture at cesarean delivery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2021;100(6):1010–1018.

- Paul MD. Bidirectional barbed sutures for wound closure: evolution and applications. J Am Col Certif Wound Spec. 2009;1(2):51–57.

- Stabile G, Romano F, De Santo D, et al. Case report: bowel occlusion following the use of barbed sutures in abdominal surgery. A single-center experience and literature review. Front Surg. 2021;8:626505.

- Anglim B, O’Connor H, Daly S. Prevena™, negative pressure wound therapy applied to closed Pfannenstiel incisions at time of caesarean section in patients deemed at high risk for wound infection. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2015 Apr;35(3):255–258.

Category: Obesity Medicine Fellow Corner, Past Articles