The Optimal Sleeve Technique to Mitigate Reflux-related Revisions

by Gregg H. Jossart, MD, FACS, FASMBS

Dr. Jossart is Director, Minimally Invasive Surgery, California Pacific Medical Center in San Francisco, California.

Funding: This supplement was sponsored by Medtronic.

Disclosures: The author has no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Bariatric Times. 2023;20(5–6 Suppl 1):S6–S7.

Key Points

- Reflux, esophagitis, and hiatal hernia occur in up to 40 percent of the bariatric population.

- Sleeve gastrectomy (SG) alone can worsen reflux and increase the presence of Barrett’s esophagus due to undetected hiatal hernias or intrathoracic migration.

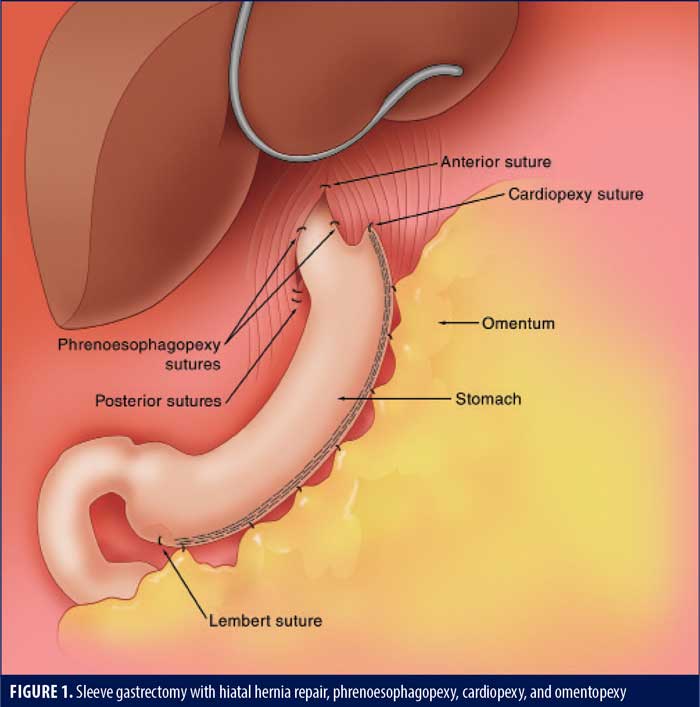

- SG in patients who have a hiatal hernia detected intraoperatively can be augmented with hiatal hernia repair, cardiopexy, and phrenoesophagopexy, as well as omentopexy, to reduce the incidence of reflux-associated problems.

- Omentopexy, independent of any hiatal hernia repair, should be done to reduce obstructive and reflux symptoms in SG patients.

The sleeve gastrectomy (SG) has emerged as the most common bariatric surgical procedure. However, concerns regarding the development of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), Barrett’s esophagus, and weight loss failure post-SG have increased in recent years. Presently, there are essentially two types of SG operations. The most common and most published is SG where the hiatus is ignored, and a significant number of patients are left with an undetected or missed hiatal hernia. They progress to develop worsening reflux, hiatal hernias, and Barrett’s esophagus and are often revised to a gastric bypass.1 The less common SG is augmented by detection and repair of a hiatal hernia, omentopexy, cardiopexy, and phrenoesophagopexy. Emerging literature suggests these additional technical components might reduce the incidence of postoperative GERD and hiatal hernia/intrathoracic migration and the need for GERD-associated revisions. The goal of this article is to provide the reader with the latest information on these additional techniques.

Historical reports have documented that up to 40 percent of bariatric patients have esophagitis or a hiatal hernia objectively documented prior to surgery.2–4 This should alert the bariatric surgeon that approximately 40 percent of patients might require a hiatal hernia repair at the time of SG.

Hiatal Hernia Repair

Historically, the Allison and Hill procedures included a full hiatal dissection and closure of the hiatus, with the Hill repair being augmented by an anterolateral imbrication anchored to the posterior hiatus. One can review these historical articles to note that they were quite effective and not the abject failures most surgeons think they are today.5,6 Modern EndoFLIP™ (Medtronic; Minneapolis, MN, US) studies have revealed that crural closure contributes to approximately 80 percent of the antireflux mechanism in hiatal hernia repairs.7,8 Thus, we now have recent objective studies supporting the concept that hiatal hernia repair, without fundoplication, is a reasonable technical option.

Daes et al9 detected and repaired (esophageal lengthening and hiatal closure) hiatal hernias in 52 percent of 373 patients undergoing SG. Persistent or de novo reflux was less than 2.6 percent at up to 22-month follow-up.9 A systematic review of 14 studies by Mahawar et al10 confirmed that hiatal hernia repair with SG has a 12.5-percent rate of postoperative GERD that is easily managed with antacid medications. In a study of 59 patients undergoing SG with a full hiatal dissection and posterior crural closure, Ece et al11 showed the percentage of patients with a DeMeester score greater than 14.7 decreased from 84 to 3 percent after surgery.

Omentopexy/Gastropexy

SG with omentopexy was first described by Santoro12 as a fixation method to reduce coiling of the stomach and associated obstructive symptoms. In a two-cohort, prospective study, Våge et al13 showed that only 14.2 percent of the gastropexy group was using acid reducing medications at one year, compared to 30.6 percent of the group without a gastropexy. A recent meta-analysis by Wu et al14 on the effect of omentopexy/gastropexy on gastrointestinal symptoms included 3,515 patients. The omentopexy group had less nausea, reflux, vomiting, bleeding, and leakage.14 There are many technical variations, from a single antral suture, a running suture, and sutures at each staple line junction (author’s preferred method, Figure 1).

Cardiopexy

Cardiopexy involves suturing the apex of the gastric staple line to the diaphragm either anterior or lateral to the inferior phrenic vein (this avoids a branch of the phrenic nerve that can cause left shoulder pain). The goal of this suture is to restore the angle of His and prevent migration of the sleeve into the mediastinum. It may be considered the apical suture of the omentopexy. It might also reduce the risk of leaks at the site where most leaks occur. In a retrospective review of 161 patients undergoing SG, Moon et al15 were not able to prove a reduced rate of symptomatic GERD at six months. Ultimately, independent effectiveness of cardiopexy may be difficult to prove, as it is often the apical suture of the omentopexy and therefore part of the omentopexy.

Phrenoesophagopexy

The phrenoesophagopexy involves suturing the esophagus to the crus at 2 to 3 locations. Ellens et al16 showed that this technique was feasible in 106 patients by placing sutures at the three, seven, and 11 o’clock locations. Follow-up was only 30 days.16 Placing these sutures during a Nissen fundoplication reduced the rate of recurrence and dysphagia in a group of 40 patients three years postoperatively.17 Hutopila et al16 recently published a series of SG patients with concomitant hiatal hernia repairs with one year of follow-up. The subgroup with phrenoesophagopexy sutures (sutures at 3 and 9 o’clock) had a rate of intrathoracic migration seven times lower than the group without a phrenoesophagopexy; severe esophagitis was four times lower. Both groups had an omentopexy, suggesting the phrenoesophagopexy is an independent antireflux technical maneuver.18

Conclusion

In summary, it is clear from the abundant literature base that SG without attention to the hiatus tends to yield worsening reflux and can potentially lead to Barrett’s esophagus and a high rate of revision to a gastric bypass due to missed hiatal hernias and intrathoracic migration. Emerging literature supports the use of intraoperative detection and repair of hiatal hernias at the time of SG. This repair should involve circumferential dissection with crural approximation anteriorly and posteriorly (Figure 1). Cardiopexy and phrenoesophagopexy should be placed to secure the distal esophagus in the abdomen. Omentopexy should be done in all SG patients to reduce the obstructive and reflux symptoms that can occur in patients with or without a hiatal hernia repair.

References

- Qumseya BJ, Qumsiyeh Y, Ponniah SA, et al. Barrett’s esophagus after sleeve gastrectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;93(2):343–352.e2.

- Dutta SK, Arora M, Kireet A, et al. Upper gastrointestinal symptoms and associated disorders in morbidly obese patients: a prospective study. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54(6):1243–1236.

- Csendes A, Burdiles P, Rojas J, et al. Pathological gastroesophageal reflux in patients with severe, morbid and hyper obesity. Rev Med Chil. 2001;129(9):1038–1043.

- Braghetto L, Korn O, Valladares H, et al. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: surgical technique, indications and clinical results. Obes Surg. 2007;17(11):1442–1450.

- Allison PR. Hiatus hernia: a 20-year retrospective survey. Ann Surg. 1973;178(3):273–276.

- Hill LD. An effective operation for hiatal hernia repair: an eight-year appraisal. Ann Surg. 1967;166(4):681–692.

- Stefanova DI, Limberg JN, Ullmann TM, et al. Quantifying factors essential to the integrity of the esophagogastric junction during antireflux procedures. Ann Surg. 2020;272(3):488–494.

- Wu H, Attaar M, Wong HJ, et al. Impedance planimetry (EndoFLIP™) reveals changes in gastroesophageal junction compliance during fundoplication. Surg Endosc. 2022;36(9):6801–6808.

- Daes J, Jimenez ME, Said N, Dennis R. Improvement of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms after standardized laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2014;24(4):536–540.

- Mahawar KK, Carr WR, Jennings N, et al. Simultaneous sleeve gastrectomy and hiatus hernia repair: a systematic review. Obes Surg. 2015;25(1):159–166.

- Ece I, Yilmaz H, Acar F, et al. A new algorithm to reduce the incidence of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2017;27(6):1460–1465.

- Santoro S. Technical aspects in sleeve gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2007;17(11):1534–1535.

- Våge V, Behme J, Jossart G, Andersen JR. Gastropexy predicts lower use of acid-reducing medication after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. A prospective cohort study. Int J Surg. 2020;74:113–117.

- Wu QL, Zhu Z, Yuan Y, et al. Effect of omentopexy/gastropexy on gastrointestinal symptoms after laparoscopoic sleeve gastrectomy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and systematic review. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2023. Epub ahead of print.

- Moon RD, Teixeira AF, Treto J, Jawad MA. Cardiopexy at the time of sleeve gastrectomy as a preventive measure for reflux. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2020;30(5):464–466.

- Ellens NR, Simon JE, Kemmeter KD, et al. Evaluating the feasibility of phrenoesophagopexy during hiatal hernia repair in sleeve gastrectomy patients. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13(12):1952–1956.

- Bardini R, Simon JE, Kemmeter KD, et al. A modification of Nissen fundoplication improves patients’ outcome and may reduce procedure-related failure rate. Int J Surg. 2017;38:83–89.

- Hutopila I, Ciocoiu M, Paunescu L, Copaescu C. Reconstruction of the phreno-esophageal ligament (R-PEL) prevents the intrathoracic migration (ITM) after concomitant sleeve gastrectomy and hiatal hernia repair. Surg Endosc. 2023;37(5):3747–3759.

Category: Supplement Articles