Conversion of Sleeve Gastrectomy to OAGB

by Helmuth T. Billy, MD

Dr. Billy is with Ventura Advanced Surgical Associates in Ventura, California; Medical Director, Bariatric Surgery, St. John’s Regional Medical Center in Oxnard, California; and Medical Director, Bariatric Surgery, Community Memorial Hospital in Ventura, California.

Funding: This supplement was sponsored by Medtronic.

Disclosures: Dr. Billy is a speaker for Medtronic, Lexington Medical, and W. L. Gore.

Bariatric Times. 2023;20(5–6 Suppl 1):S4–S5.

Key Points

- Learn how to identify the anatomic landmarks in revision of sleeve gastrectomy (SG) to one anastomosis gastric bypass (OAGB).

- Learn how to perform a reproducible and standardized revision to OAGB.

- Review important steps in the preoperative evaluation of SG prior to OAGB.

Sleeve gastrectomy (SG) continues to be one of the most popular and commonly performed bariatric operations in the world, accounting for over 53 percent of bariatric operations, compared to Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), which accounts for 30 percent.1 SG frequently requires revision due to gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and weight regain, and revision can occur in at least 30 percent of patients following SG.2 Weight regain is reported to occur in 5.7 percent of patients at two years, increasing to a staggering 75.6 percent at six years.3 Revisional one anastomosis gastric bypass (OAGB) after SG is becoming increasingly popular following the 2022 endorsement of OAGB as a primary bariatric operation by the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS). A 2022 systematic review and meta-analysis of multiple revisional procedures following SG, including endoscopic gastroplasty (ESG), re-SG, RYGB, OAGB, single anastomosis duodenoileal bypass (SADI), and duodenal switch (DS), suggested that revisional OAGB was the most effective operation.4

OAGB as a revisional operation following SG is an efficient, straightforward operation that avoids the more challenging dissection and anastomosis associated with the RYGB and DS operations. Revisional RYGB following SG has been associated with a higher, 7.2-percent overall complication rate when compared to primary RYGB.5 Revision from SG to OAGB avoids the two anastomoses necessary with the RYGB, eliminates the mesenteric defect associated with internal herniation at the enteroenterostomy, and maintains weight loss that is comparable to RYGB.6

SG is ideally suited for utilizing OAGB as a revisional approach. SG that has resulted in dilation of the gastric conduit can be resected using a 40 French bougie. The high pressure system associated with SG is decompressed with a single anastomosis, while still preserving a long gastric conduit and requiring minimal operative dissection. Successful revision from SG to OAGB is a reproducible operation that can be standardized between surgeons.

As a revisional operation that requires less operative dissection, OAGB is a time-efficient operation that lends itself well to short hospital stays or outpatient procedures. There are several important steps that contribute to a reproducible operation, thus maintaining consistency of the overall operation. Each patient undergoes preoperative assessment, including upper gastrointestinal (GI) swallow to assess gastric sleeve dilation and severity of reflux. SG has been associated with conversion to Barrett’s esophagus,7 and each patient undergoes preoperative EGD with distal esophageal biopsies at multiple levels. Bile reflux following SG is a common finding on preoperative EGD, and those patients with evidence of changes due to Barrett’s esophagus are ruled out as OAGB candidates. Successful insurance authorization is enhanced with those patients requiring revision for GERD-related complications who are demonstrated to have significant gastroesophageal reflux on upper GI swallow, distal esophagitis on EGD proven biopsy, and bile reflux requiring biliary diversion utilizing an antral transection and gastrojejunostomy. Key anatomic steps include the following operative goals:

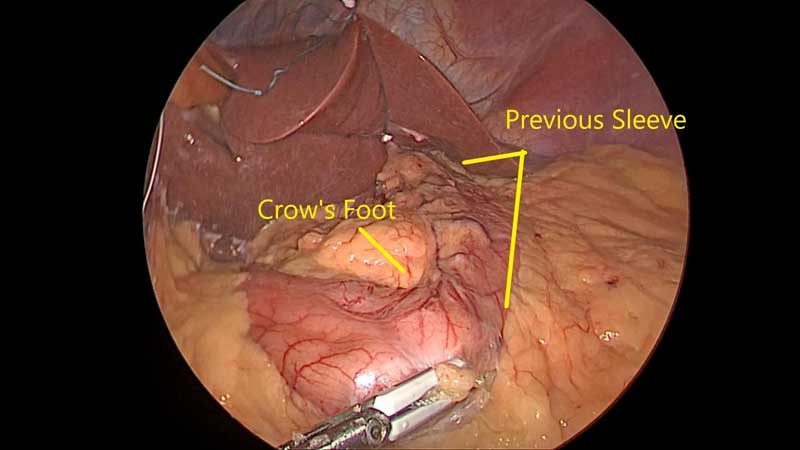

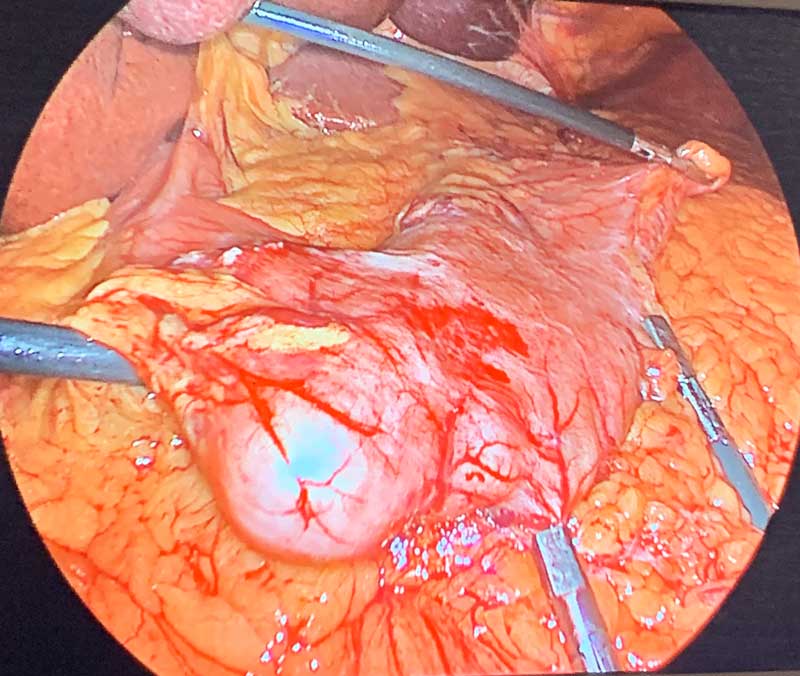

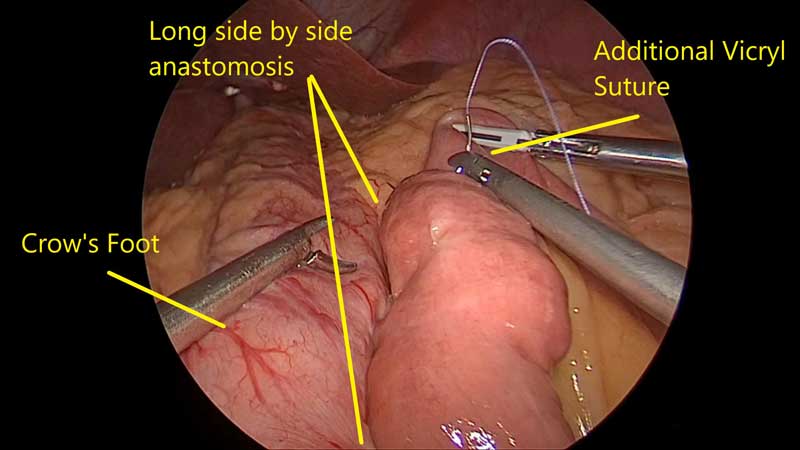

- Identification of the “crow’s foot” as an anatomic landmark (Figure 1). Maintaining a gastric conduit that is between 12 and 15cm will require a dissection that begins 1 to 2cm below the crow’s foot, between the angularus incisura and the pylorus.

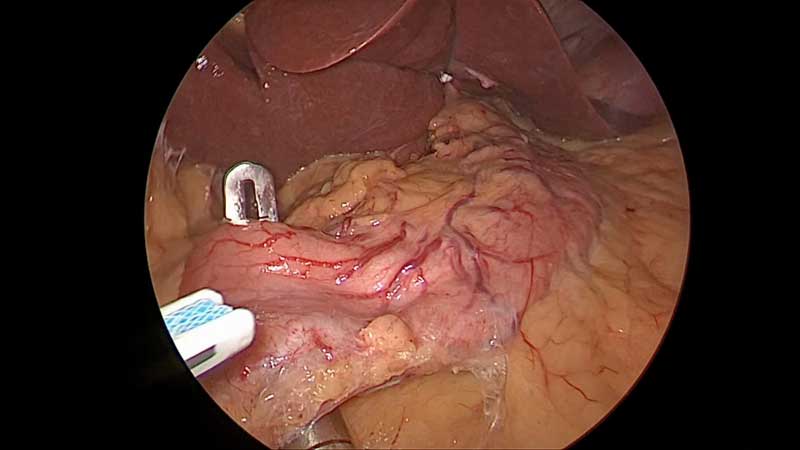

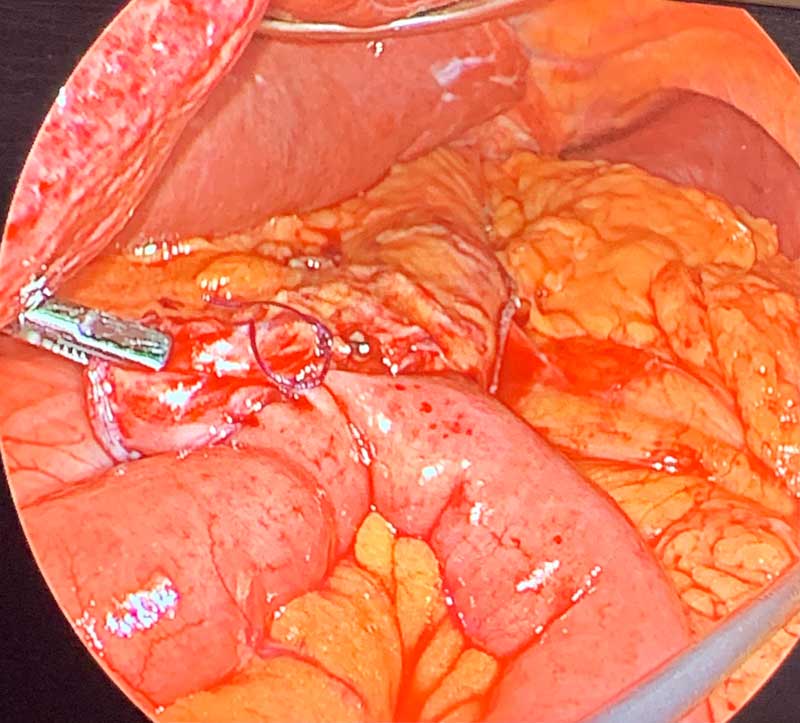

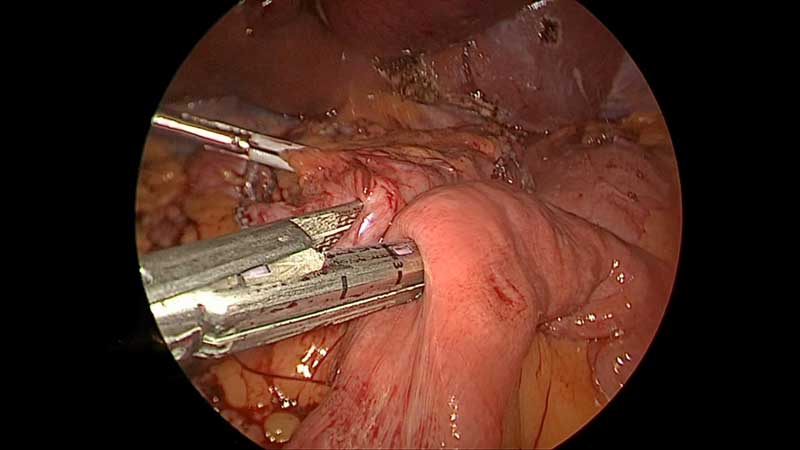

- A dissection 1 to 2cm below the crow’s foot along the lesser curvature of the stomach is required to allow entry into the lesser sac (Figure 2).

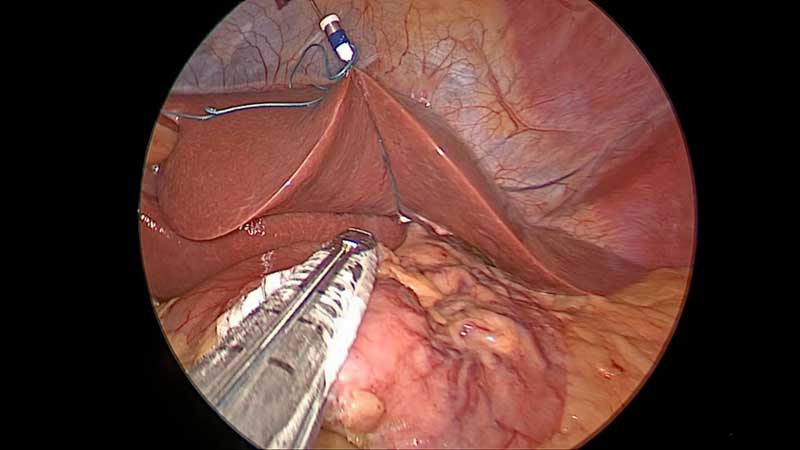

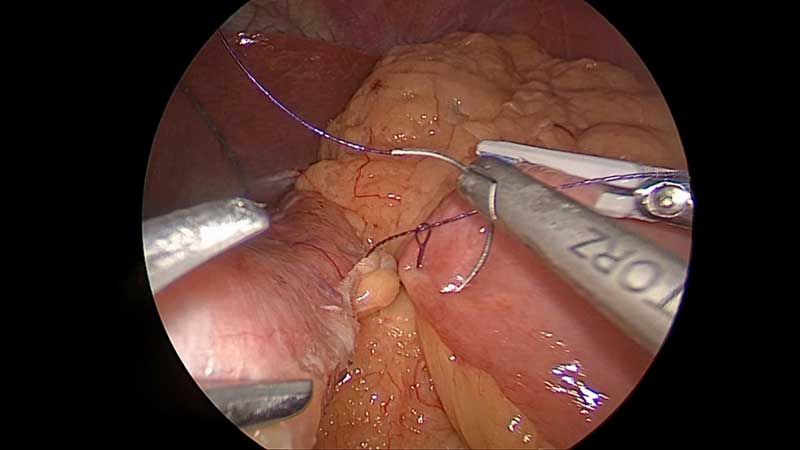

- Upon entering the lesser sac, a posterior gastric dissection behind the antrum is necessary for stapler placement, which will allow transection of the antrum below the crow’s foot and creation of the 12 to 15cm gastric conduit (Figure 3).

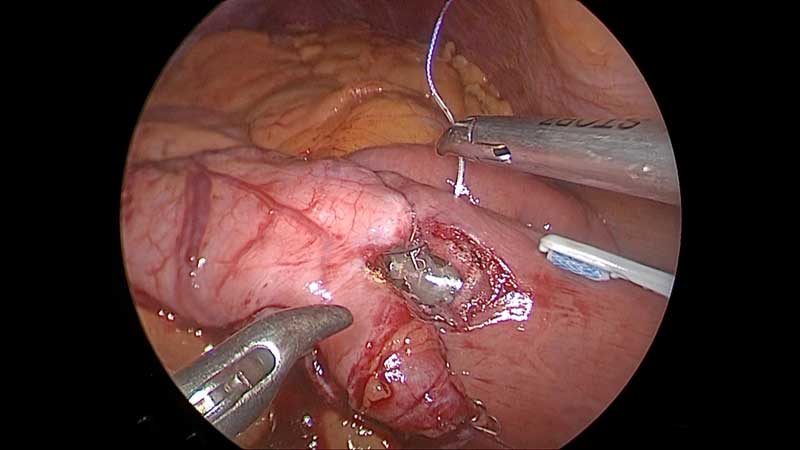

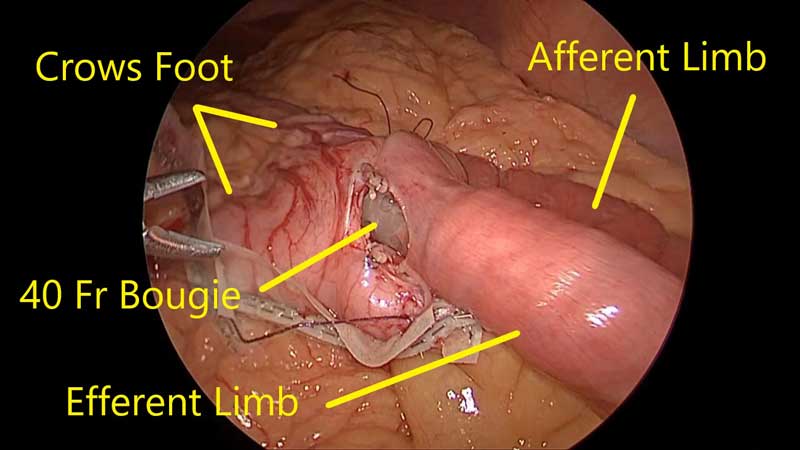

- Once the antrum has been transected below the crow’s foot, a 40 French bougie is positioned, and the gastric conduit can be assessed (Figure 4).

- If a hiatal hernia is present, the hiatal hernia is repaired.

- If the gastric conduit appears significantly dilated, a lateral gastric resection (re-sleeve) is considered and performed, if necessary (Figures 5–7).

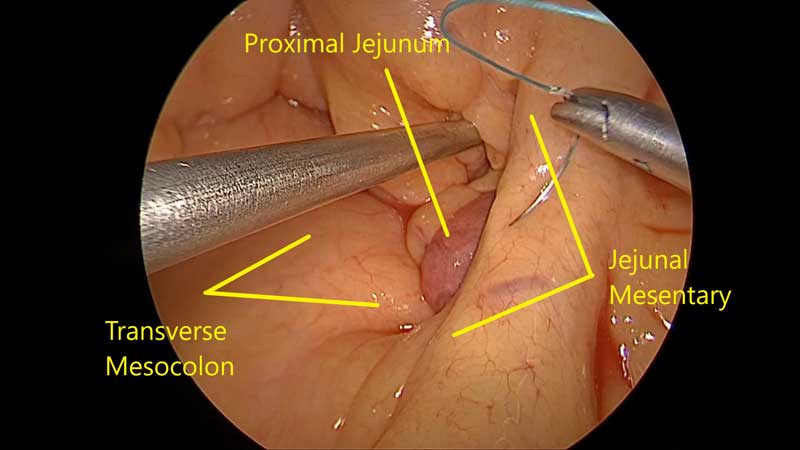

- The ligament of treitz is identified, and a 200cm bilioancreatic limb is carefully measured.

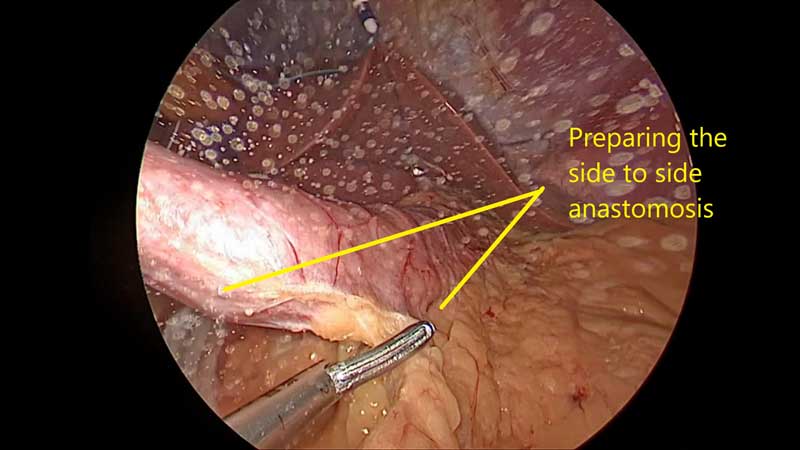

- The mesenteric border of the biliopancreatic limb at the proposed gastrojejunostomy is approximated to the distal gastric conduit (Figure 8).

- The common channel (efferent limb) is carefully measured to ensure that there is at least 350cm of distal common channel. In the event the common channel is less than 350cm, the biliopancreatic limb is appropriately shortened to preserve a 350cm common channel.

- The gastrojejunostomy is performed using a hand-sewn technique or 45mm linear staple anastomosis (Figure 9–11).

- The mesenteric defect between the mesentery of the efferent limb and the transverse mesocolon is closed using a nonabsorbable suture (Figure 13).

Patients are discharged either the same day or after an overnight stay and are maintained on proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy for 3 to 6 months. OAGB after SG has the appeal of being relatively easy to perform, compared to SADI operations, and has weight loss data that consistently demonstrate outcomes comparable to or better than RYGB. When following the above steps and maintaining a reproducible approach to revision of SG to OAGB, the operation becomes a reliable and effective alternative to RYGB.

Video: See Dr. Billy perform conversion of sleeve gastrectomy to one anastomosis gastric bypass.

References

- Angrisani L, Santonicola A, Iovino P, et al. IFSO worldwide survey 2016: primary, endoluminal, and revisional procedures. Obes Surg. 2018;28(12):3783–3794.

- Silecchia G, De Angelis F, Rizzello M, et al. Residual fundus or neofundus after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: is fundectomy safe and effective as revision surgery? Surg Endosc. 2015;29(10):2899–2903.

- Lauti M, Kularatna M, Hill AG, MacCormick AD. Weight regain following sleeve gastrectomy–a systematic review. Obes Surg. 2016;26(6):1326–1334.

- Franken RJ, Sluiter NR, Franken J, et al. Treatment options for weight regain or insufficient weight loss after sleeve gastrectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2022;32(6):2035–2046.

- Dang JT, Vaughan T, Mocanu V, et al. Conversion of sleeve gastrectomy to Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: indications, prevalence, and safety. Obes Surg. 2023;33(5):1486–1493.

- Hany M, Zidan A, Elmongui E, Torensma B. Revisional Roux-en-Y gastric bypass versus revisional one-anastomosis gastric bypass after failed sleeve gastrectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Obes Surg. 2022;32(11):3491–3503.

- Genco A, Castagneto-Gissey L, Lorenzo M, Ernesti I, et al. Esophageal adenocarcinoma after sleeve gastrectomy: actual or potential threat? Italian series and literature review. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2021;17(5):848–854.

Figure 1. Identification of the “crow’s foot” as an anatomic landmark.

Figure 2. Begin a dissection 1-2 cm below the crow’s foot along the lesser curvature of the stomach to allow entry into the lesser sac.

Figure 3. Upon entering the lesser sac, begin a posterior gastric dissection behind the antrum to allow stapler placement which will allow transection of the antrum below the crow’s foot and creation of the 12-15 cm gastric conduit.

Figure 4. Once the antrum has been transected below the crow’s foot a 40 french bougie is positioned and the gastric conduit can be assessed.

Figures 5–7. If the gastric conduit appears significantly dilated a lateral gastric resection (re-sleeve) is considered and if necessary performed.

Figure 8. The mesenteric border of the biliopancreatic limb at the proposed gastrojejunostomy is approximated to the distal gastric conduit.

Figures 9–11. The gastrojejunostomy is performed using a hand sewn technique or a 45 mm linear staple anastomosis.

Figure 12. Passing the bougie for the one anastomosis gastric bypass.

Figure 13. The mesenteric defect between the mesentery of the efferent limb and the transverse mesocolon is closed using nonabsorbable suture.

Category: Supplement Articles