Perforated Marginal Ulcer Secondary to Marijuana Smoking

by Ari Sapin, MD; Anirudha Goparaju, MD; Jun Levine, MD, FACS, FASMBS; Venkata Kella, MD; Patricia Cherasard, PhD, MBA, PA-C; and Collin Brathwaite, MD, MS, FACS

All authors are with the Department of Surgery, NYU Langone–Long Island in Mineola, New York.

Funding: No funding was provided for this article.

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Bariatric Times. 2022;19(8):12–13.

Abstract

Historically, smoking and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use have been the most common causes of marginal ulcer formation in the bariatric population. However, with more patients reporting marijuana use, it is essential, as providers, to counsel patients that marijuana smoking can also increase their risk of marginal ulcer formation. We present a patient with a perforated marginal ulcer whose only risk factor was marijuana smoking.

Keywords: Marginal ulcer, marijuana

In 2019, there were over 256,000 bariatric procedures performed in the United States (US). The majority of procedures currently performed are sleeve gastrectomies; however, almost 20 percent of these patients (about 50,000) underwent a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB).1 RYGB was developed by Ed Mason et al2 in the 1960s and has been modified over the years to be performed as a minimally invasive procedure with fewer complications. The first laparoscopic gastric bypass was performed by Alan Wittgrove in 1994.2

However, even with newer technology and knowledge about human physiology, this procedure still comes with risks. One of the biggest risks is marginal ulcers, which refer to the development of mucosal erosion at the gastrojejunal anastomosis.2 The incidence of marginal ulcers ranges from 0.6 to 16 percent.2 There has been ongoing debate over the years concerning the etiology of how marginal ulcers develop, and current data supports high gastric pouch acidity.3 A number of risk factors have been studied and identified as contributing to marginal ulcer formation, with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents and smoking being the main contributors.4 When counseling patients, the common teaching is to educate and encourage tobacco and nicotine cessation.

It is important, due to the legalization of marijuana in states across the country and increased incidence of consumption, that we counsel our bariatric patients about the pitfalls of marijuana smoking, as it could potentially lead to marginal ulcer formation the same way cigarette smoking does.5 We present a case report about a patient who presented to our institution with a perforated marginal ulcer whose only identifiable risk factor was marijuana smoking.

Case Report

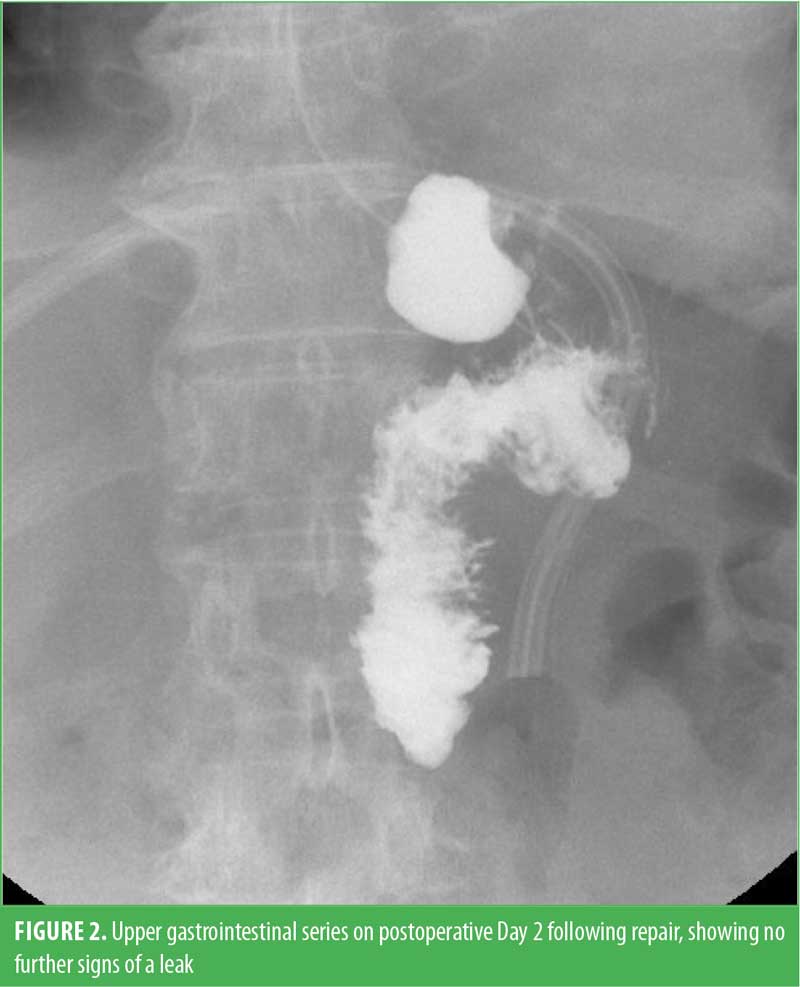

A 65-year-old female patient presented to our emergency room with a one-day history of severe left upper quadrant abdominal pain and nausea. Her past medical history included hypertension, well-controlled with medication, and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), for which she used a continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) machine at night. Her past surgical history was significant for a laparoscopic RYGB 10 months prior. She denied any recent nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use or cigarette smoking. Her vital signs were within normal limits. On the physical exam, she was tender and exhibited guarding and rebound in the left upper quadrant. Her lab work was significant for leukocytosis, with a white blood cell count of 15.7/μL. Computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis was performed, which showed free peritoneal air and a small volume of extraluminal contrast near the gastrojejunal anastomosis concerning for a perforation, likely from a marginal ulcer (Figure 1). She was started on broad spectrum antibiotics and antifungals and booked to go to the operating room for a diagnostic laparoscopy. In the operating room, purulent peritonitis was encountered, and a 3mm marginal ulcer was identified on the jejunal side of the gastrojejunal anastomosis. The ulcer was repaired primarily and buttressed with omentum for a Graham patch repair. The abdomen was thoroughly irrigated with six liters of saline. The patient did well postoperatively, with an upper gastrointestinal series on postoperative Day 2 showing no signs of a leak (Figure 2). She was started on a diet and discharged home on postoperative Day 3. On further questioning, while the patient was in the hospital, she admitted to smoking marijuana multiple times a day for many years to help with her anxiety.

Discussion

Even though marijuana is still considered a Class 1 federally illegal drug in the US, almost 20 percent of Americans used it at least once in 2019.5 Over the past decade, many states have legalized the use of marijuana, and there are currently 18 states that allow its consumption.6 Marijuana can be consumed in a multitude of different ways, including edibles, transdermal patches, pills, vapes, and topicals. However, the oldest and most common method of consumption is smoking, whether it is through a pipe, bong, joint, or blunt.

There are several mechanisms by which smoking is proposed to increase the risk of postoperative complications that relate to both the acute effects of smoking on the human body and the long-term disease processes related to smoking. In the acute setting, smoking leads to altered wound healing through several mechanisms. Smoking damages the cells that line the blood vessels, which leads to an increase in the permeability of the vascular system. Vasospasm and swelling then lead to the activation of the sympathetic nervous system.6 Within the coagulation cascade, platelet aggregation increases and prostaglandins decrease, which leads to further breakdown of tissue barriers. An increase in the availability of carbon monoxide binding to hemoglobin also decreases the oxygen-carrying capacity of blood, therefore interfering with normal tissue healing.7 The nicotine in tobacco has also been known to contribute to states of hypercoagulability and hypoxia. Additionally, the effects of smoking on the pulmonary system include an increase in airway inflammation and overall blunting of the pulmonary immune system by inhibiting alveolar macrophages and ciliary clearance.7

While marijuana smoke does not contain nicotine, it has been shown to have similar toxic chemicals, such as naphthalene, acrylamide, and acrylonitrile.8 Marijuana smokers tend to inhale more deeply and hold their breath longer than cigarette smokers, which leads to a greater exposure per breath to tar.9 There have been many studies looking at how marijuana smoke affects the lungs. Smoking marijuana can cause chronic bronchitis, and marijuana smoke has been shown to injure the cell linings of the large airways, which could explain why smoking marijuana leads to symptoms such as chronic cough, phlegm production, wheezing, and acute bronchitis.10 Smoking marijuana hurts the lungs’ first line of defense against infection by killing cells that help remove dust and germs, as well as causing more mucus to be formed.11

Smoking any amount of tobacco after undergoing bariatric surgery is a risk factor for marginal ulcer development.12 Therefore, more research is needed regarding whether or not any amount of marijuana smoking after bariatric surgery can increase the risks of marginal ulcers as well.

Conclusion

During the initial encounter with a patient being evaluated to undergo bariatric surgery, it is important to not only go over the risks of tobacco smoking and its relationship to developing marginal ulcers, but to counsel them on the potential risks of marijuana smoking and the potential to develop marginal ulcers.

References

- American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. Estimate of bariatric surgery numbers, 2011–2020. Jun 2022. https://asmbs.org/resources/estimate-of-bariatric-surgery-numbers. Accessed 21 Jul 2022.

- American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. Story of obesity surgery. Jan 2004. https://asmbs.org/resources/story-of-obesity-surgery. Accessed 21 Jul 2022.

- Racu C, Mehran A. Marginal ulcers after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: pain for the patient…pain for the surgeon. Bariatric Times. 2010;7(1):23–25.

- Azagury DE, Abu Dayyeh BK, Greenwalt IT, Thompson CC. Marginal ulceration after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery: characteristics, risk factors, treatment, and outcomes. Endoscopy. 2011;43(11):950–954.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Data and Statistics. Reviewed 8 Jun 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/marijuana/data-statistics.htm. Accessed 21 Jul 2022.

- Hansen C, Alas H, Davis Jr. E. Where is marijuana legal? A guide to marijuana legalization. US News. 6 Jan 2022. https://www.usnews.com/news/best-states/articles/where-is-marijuana-legal-a-guide-to-marijuana-legalization. Accessed 4 Apr 2022.

- Muleta H. Smoking associated postoperative complications of bariatric surgery: a review. Bariatric Times. 2018;15(10):22–23.

- Lamotte S. Toxins in marijuana smoke may be harmful to health, study finds. CNN Health. 11 Jan 2021. https://www.cnn.com/2021/01/11/health/weed-marijuana-smokers-toxins-wellness/index.html. Accessed 4 Apr 2022.

- Wu TC, Tashkin DP, Djahed B, Rose JE. Pulmonary hazards of smoking marijuana as compared with tobacco. N Engl J Med. 1988;318(6):347–351.

- Howden ML, Naughton MT. Pulmonary effects of marijuana inhalation. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2011;5(1):87–92.

- Tashkin DP. Effects of marijuana smoking on the lung. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2013;10(3):239–247.

- Dittrich L, Schwenninger MV, Dittrich K, et al. Marginal ulcers after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: analysis of the amount of daily and lifetime smoking on postoperative risk. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2020;16(3):389–396.

Category: Case Report, Past Articles