The Case for Metabolic Surgery: Lessons from the 4th World Congress on Therapeutic Interventions for Diabetes

by Adrian Dan, MD, FACS, FASMBS, Column Editor

by Adrian Dan, MD, FACS, FASMBS, Column Editor

Dr. Dan is Medical Director, Weight Management Institute at Summa Health in Akron, Ohio, and Associate Professor of Surgery at Northeastern Ohio Medical University (NEOMED) in Rootstown, Ohio

Funding: No funding was provided.

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

This is the inaugural article in a quarterly column edited by Adrian Dan, MD, FACS, FASMBS, that is designed to bring attention to current topics and issues pertinent to professionals treating the disease of obesity.

Bariatric Times. 2020;17(1):9–10

Imagine the following experiment that was suggested to me by a wise colleague. Ask one of your medical students, who is enthusiastically scrubbing on a laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB), to tell you what they know about Type 2 diabetes. I recently tried this bit with a bright young student doctor who was able to tell me an impressive amount of details about the pathophysiology, diagnostic work-up, and medical therapy of the condition. When asked if surgery had any role in its management, he did mention amputations and then realized he had been set up. He did redeem himself with some help from the surgical resident, who was a tad more in tune with my ploy, and indicated that he had just recently learned on this rotation about the potential for remission of diabetes with bariatric surgery.

Like much of our readership, I spend my days caring for patients afflicted with obesity and diabetes. Long before its much overdue designation as a disease by the American Medical Association (AMA) in 2013, we have recognized obesity to be a ravaging condition associated with a multitude of ailments, such as Type 2 diabetes. Attending the 4th World Congress on Therapeutic Interventions for Diabetes in New York, New York, on April 8 to 10, 2019, a multidisciplinary global symposium, has further solidified my understanding of this disease and had me rethinking how medical professionals and the general public perceive obesity and its treatment.

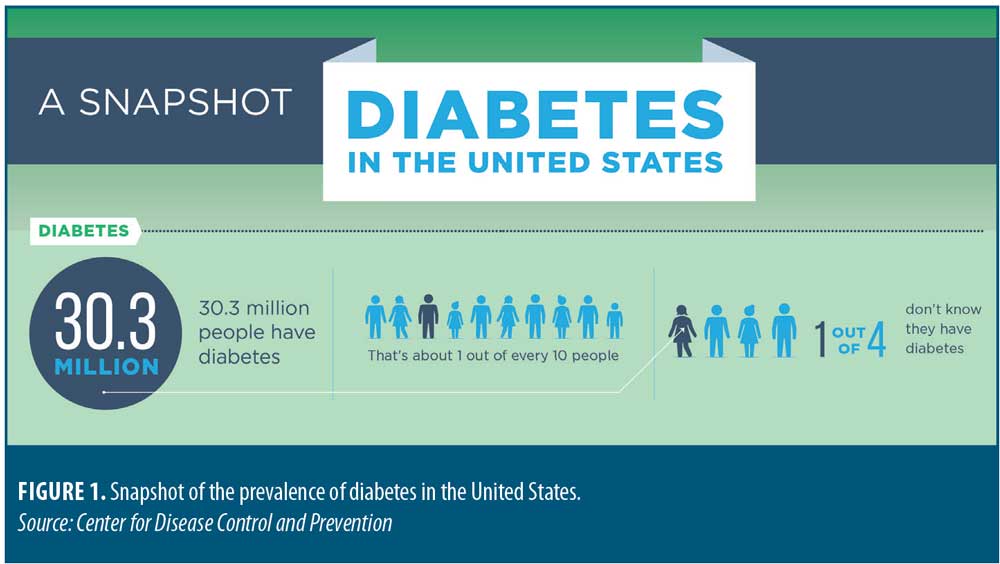

The prevalence of obesity and diabetes in the United States are estimated to be at 40 percent (~100 million) and 10 percent (~30 million), respectively (Figure 1). According to the American Diabetes Association, the total cost of diagnosed diabetes in the United States in 2017 was a staggering $327 billion. With the multitude of randomized trials and the observational studies that show a substantial remission rate of Type 2 diabetes with LRYGB, the astounding underutilization of our operations remains a point of considerable frustration among bariatric surgeons. Our societal beliefs remain that the consequences of obesity are social rather than medical. On average, a considerable knowledge gap remains in our understanding of obesity and in the medical community’s overall awareness of the robust body of evidence that now exists to support its definition as a disease. This is a result of the deficit of obesity education in most medical schools and residency programs, and also because most of the supporting evidence generated by researchers from around the world is still fairly new. Scientific breakthroughs in our understanding of the mechanisms of the disease of obesity are elucidating in convincing fashion how our metabolic make-up is largely responsible for the loss of weight regulation. Some notable areas of exploration, although way too many to mention here, include the human microbiome, gut hormones, bile-acid circulation, neuro-endocrine response to food intake, and genetics.

Earlier in my career, I myself counseled patients with the viewpoint that it all boils down to “calories in versus calories out” and that bariatric procedures only work by “restriction and/or malabsorption.” While I know better now, that dogma still persists in many circles of clinicians, most of whom have not had the benefit of learning about the newly gained advancements in the understandings of the disease. Misinformation can lead to misconceptions about the causes of obesity and the reliance solely on diet and exercise in situations where the underlying metabolic mechanisms of the disease can make such therapies futile. Furthermore, it perpetuates the false assumption that individuals with obesity have the necessary control within their grasp and that their lack of will-power and discipline is the real obstacle. Such bias is often internalized by patients and leads to self-blame, lack of self-esteem, and loss of interest in seeking effective therapy for their affliction.

As it turns out, the original simplistic theories on weight gain and mechanisms of action by which bariatric operations work were off their mark. Bariatric surgery, however, has provided a platform upon which researchers have been able to discern the metabolic implications of such operations and make countless advances in the understanding of human nutrition and metabolism. This itself could set up future metabolic discoveries that might eventually be as effective as surgery. As our understanding of these mechanisms evolve, so must the focus from obesity surgery to surgical therapy delivered to repair the metabolic derangements responsible for obesity and Type 2 diabetes. While focusing so much on the obvious benefits of long-term sustainable weight loss, we have omitted to stress to the general public and the medical community that we consistently impact and often cure Type 2 diabetes.

The evidence appears clear that obesity and diabetes are diseases of metabolic dysfunctions that are far more complex than initially thought. Our patients suffer not from lack of will power and discipline but from a metabolic disease. As a result, many groups and societies, including the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS), have changed their names to reflect this facet. Clinical centers have now rebranded their names and their messages to finally be more palatable to the general public. The notion of metabolic surgery and medicine might be the avenue to overcoming the stigma that is attached to words such as “weight,” “morbid,” and “obese,” stigma that will likely take generations for us to overcome. Metabolic medicine and surgery, and even diabetes surgery as some have proposed, might be the essential opportunity to rebrand our specialty. In this manner, surgical intervention for amelioration of metabolic dysfunction and diabetes might be associated with less prejudice and bias. We could finally bridge the educational gap on obesity in the medical community and, most importantly, finally gain the public acceptance for our operations as the life-saving therapy they have been proven to be.

Guest Perspective

by Walter Pories, MD, FACS

Dr. Pories is Professor of Surgery, Biochemistry, and Kinesiology, Brody School of Medicine, East Carolina University, Greenville, North Carolina.

It makes no sense. How could removing half of a healthy stomach produce full and durable remission of Type 2 diabetes in less than a week, before there is any significant change in adiposity? It leads to full remissions, with prevention of blindness, renal failure, amputations, and even reduced all-cause mortality by 73 percent.1

Furthermore, how could the same procedure also reverse hypertension, severe obesity, dyslipidemia, nonalcoholic steatotic hepatitis (NASH), and even polycystic ovary syndrome? Even more puzzling is that the same effects can be produced by the gastric bypass, the duodenal switch, as well as other very different operations on the foregut.

It might not make sense, but these observations are true and suggest diabetes, obesity, and NASH are not three different diseases but are only different expressions of a metabolic defect that appears to be in mitochondrial membranes, perhaps caused by a signal from the proximal intestinal mucosa.

These new findings are most encouraging, but these new approaches are most costly, and cruel diseases also present big challenges. How should we treat patients who have faithfully controlled their glucose values with insulin, now that we are learning that this might be harmful? How can we decide who should have the surgery? What are the long-term effects and complications of these procedures? Who should provide that care?

I therefore applaud Dr. Adrian Dan’s intent to offer a series of articles for primary care physicians, consultants, patients, and insurance carriers to provide a long-needed impartial overview of the metabolic syndrome, as well as currently accepted optimal medical and surgical therapy. That communication is long overdue.

Reference

- MacDonald KG Jr, Long SD, Swanson MS, et al. J Gastrointest Surg. 1997;1(3):213–220; discussion 220.

Category: Past Articles, Perspectives