The Importance of Anesthesiology in Treating Bariatric Surgery Patients

Bariatric Times. 2018;15(6):16–18.

Funding: No funding was provided for this article.

Disclosures: The author has no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

An interview with:

An interview with:

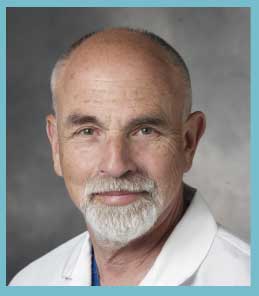

Jay B. Brodsky, MD

- Professor (Anesthesia), Associate Medical Director of Perioperative Services, Stanford University Medical Center, in Stanford, California

- 1971: Graduated from State University of New York Upstate Medical School, Syracuse, New York

- 1971–72: Intern at SUNY Upstate in Medicine.

- 1972–75: Anesthesia residency at Beth Israel Hospital, Harvard Medical School

- 1975-77: US Army, rank Major. Stationed at Letterman Army Medical Center, Presidio of San Francisco, in San Francisco, California

- 1977 to present: Faculty member, Department of Anesthesia at Stanford University School of Medicine

- 1988–present: Professor of Anesthesia

- Former Medical Director of the Postoperative Care Units and Former Medical Director of Operating Rooms at Stanford University, Stanford, California

- Co-founder, International Society for the Perioperative Care of the Obese Patient (ISPCOP)

Compared to patients of normal weight, are the anesthesiology needs of a patient with obesity different when undergoing surgery?

Dr. Brodsky: Bariatric patients, by nature of their obesity alone, have an altered anatomy and physiology. In addition, patients with obesity often have medical comorbidities, which can affect anesthesia management. As anesthesiologists, we must manage patients with obesity differently than other patients.

For example, lung volume is reduced in obesity, especially when a patient with obesity lies flat. Anesthesia is normally induced with the patient supine. However, in the patient with obesity, the supine position might cause the patient’s oxygen levels to rapidly desaturate, resulting in hypoxemia. The endotracheal tube must be inserted as quickly as possible once the patient is given muscle relaxants. Complete preoxygenation before inducing a patient with obesity is very important. A patient with obesity should also be induced with the head and upper body elevated in the head elevated laryngoscopy position (HELP), often with the operating room table in reverse Trendelenburg position. These steps improve the view during laryngoscopy, increasing tracheal intubation success and prolonging the patient’s “safe apnea time,” (i.e., the time between paralysis for intubation until the oxyhemoglobin drops to a critical level of 90 to 92%).

Mask ventilation is frequently more difficult in patients with obesity when compared to patients of normal weight. The anesthesiologist often needs a second pair of hands—one person to hold the face mask and to lift the patient’s jaw, while the second person squeezes the bag to ventilate.

The 4th National Audit Project (NAP4) audit of major complications of airway management in the United Kingdom1 documented a significant incidence of morbidity and mortality from gastric aspiration in patients with obesity ventilated through a supraglottic airway. In my opinion, intubation with an endotracheal tube for controlled ventilation during laparoscopy is mandatory for patients with obesity. This has become a controversial topic since some of my European colleagues use a laryngeal mask airway during laparoscopic bariatric operations. The newer supraglottic airways that include gastric ports for suctioning might reduce that risk; however, there are no studies yet to demonstrate the safety.

Obviously, proper padding and physiologic positioning are extremely important to avoid pressure sores and stretch injuries. A patient with extreme obesity, especially during long-duration procedures, is at great risk for developing rhabdomyolysis, a breakdown of muscle tissue that releases a damaging protein into the blood. Significant muscle breakdown can lead to renal failure, electrolyte disturbances, and compartment syndromes. Besides padding, the anesthesiologist must adequately hydrate bariatric patients intra-operatively to reduce the risk of rhabdomyolysis.

Do you think anesthesiologists should undergo special training in the management of patients with obesity?

Dr. Brodsky: All anesthesiologists and nurse anesthetists must be familiar with the special needs of these patients. Most residency programs, including ours at Stanford University, have rotations for anesthetic management of bariatric patients. All major anesthesia meetings have sections dealing with anesthesia and obesity, anesthesiology journals frequently publish clinical studies in this area, and there are several textbooks entirely devoted to this subject. The information is definitely out there.

Several anesthesia specialty societies are dedicated to educating anesthesiologists on the special needs of patients with obesity, including the International Society for the Perioperative Care of the Obese Patient (ISPCOP) and its European counterpart (ESPCOP), and the United Kingdom’s Society of Bariatric Anaesthetists (SOBA). Each of these groups has a website to disperse information and their own educational venues for anesthesia professionals who are not specialists in the field.

When did you develop an interest in anesthesia and obesity?

Dr. Brodsky: Extreme obesity was rare when I started my career 45 years ago. We didn’t understand the unique needs of these patients, and even areas as important as the proper dosages of anesthetic drugs in obesity were unknown. Additionally bariatric surgery was not that common. We had two surgeons at Stanford—Roy Cohn and Ron Merrill—both of whom performed open gastric stapling operations. Their patients were very big—what we would call “super obese” today. Of course, body mass index (BMI) was not used to describe obesity classes back then.

I found anesthetizing these patients to be complex, and I always enjoyed the challenging aspects of anesthesia. The very first surgical patients to have epidural opioids for postoperative analgesia at our hospital back in the early 1980s were my bariatric patients. The results were so profound we expanded our intra- and postoperative epidural management to all types of procedures for all patients. Over the years, we have continued to develop and refine management techniques to meet the challenges of obesity. With my colleagues, Harry Lemmens and Jerry Ingrande, we’ve had several important studies published on airway management, anesthetic drug dosing, patient positioning, and almost every aspect of anesthesia for bariatrics.

What are some lessons anesthesiologists can apply to managing patients with obesity undergoing procedures other than bariatric operations?

Dr. Brodsky: Most anesthesia reports on obesity come from studies of bariatric patients. With the tremendous worldwide increase in obesity, the lessons we have learned from the bariatric surgery speciality are now being applied to all areas of surgery that treat patients with obesity. The most important lessons being applied include positioning for anesthetic induction, ensuring adequate preoxygenation, having a trained assistant close by if needed, and using video laryngoscopy if difficult intubation is anticipated. Other lessons include appropriate drug dosing based on lean body weight (not total body weight), controlled mechanical ventilation with an endotracheal tube, goal-directed intravenous fluid management, prophylaxis for postoperative nausea, and multimodal analgesia. These same concerns gained from our extensive experience with bariatrics are applied to nonbariatric patients with obesity.

What future developments in anesthesia for patients with obesity do you anticipate?

Dr. Brodsky: Even more minimally invasive procedures are replacing laparoscopy for obesity management, including gastric balloons and natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES). The anesthesiologist must tailor the management of their patients when shorter, less invasive and less painful procedures are performed. Fast-track techniques to enable short-stays in the post-anesthesia care unit (PACU) and in ambulatory surgical centers, with minimal pain and reduced postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV), are being developed. For example, there is a lot of interest in opioid-free anesthesia. Since so many patients with obesity have obstructive sleep apnea, the reduction or complete elimination of opioid drugs during anesthesia will presumably reduce postoperative morbidity.

It has been exciting for me to have participated in the evolution of anesthetic practice for surgical patients with obesity during my career. When I started, anesthesiologists considered every patient with obesity to be at high risk for anesthetic complications. Awake fiberoptic intubation to establish an airway was once recommended for all patients with morbid obesity, but now it is seldom performed. High dosages of potent opioids have been replaced with a multimodal approach to analgesia. Today, with appropriate management by skilled anesthesiologists, patients with obesity now share the same rate of anesthetic complications as patients of normal weight.

References

- 4th National Audit Project (NAP4) of the Royal College of Anaesthetists and the Difficult Airway Society. March 2011. https://www.rcoa.ac.uk/nap4. Accessed May 19, 2018.

Category: Interviews, Past Articles