Reducing Early Hospital Readmission Rates After Bariatric Surgery

by Payal Sharma, MSN, RN, FNP-BC, CBN, and Soohyun Nam, PhD, APRN, ANP-BC

by Payal Sharma, MSN, RN, FNP-BC, CBN, and Soohyun Nam, PhD, APRN, ANP-BC

Ms. Sharma and Dr. Nam are with the Yale University School of Nursing in Orange, Connecticut.

Funding: No funding was provided.

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Abstract: Bariatric surgery is a well-established means of treating obesity but readmission after surgery is a prevalent problem. Nausea, vomiting, dehydration, and abdominal pain are the most common, but preventable causes of readmission after bariatric surgery. Understanding the underlying reasons and factors associated with postsurgical readmission and exploring current interventions might help healthcare providers identify high-risk patients and target therapy to reduce avoidable early readmission.

Keywords: bariatric surgery, sleeve gastrectomy, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, readmission, readmissions, readmission rates, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, dehydration, adjustable gastric band, complications

Bariatric Times. 2019;16(6):12–15.

The obesity epidemic is a major public health concern globally. Since 1980, the prevalence of obesity worldwide has doubled to 30 percent in the adult population.1 The prevalence of clinically severe obesity (body mass index [BMI]>40kg/m2) in adults, however, has increased at an even faster rate, quadrupling from 1986 through 2000 to 4.8 percent.1 As the prevalence of obesity rises, so does the demand for successful therapies. Bariatric surgery remains the most effective treatment option for individuals who have clinically severe obesity. It is one of the most frequently performed operations in North America. However, early readmission (i.e., 30-day readmission) after bariatric surgery remains a prevalent problem.1,2

Bariatric surgery is the surgical alteration of the stomach and/or intestine to produce weight loss. There are four types of bariatric surgery, including sleeve gastrectomy (SG), Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), adjustable gastric band (AGB), and biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD-DS). Patients who have a BMI of at least 40kg/m² or at least 35kg/m² plus one or more obesity-related comorbidity, such as Type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and obstructive sleep apnea, are considered potential candidates for bariatric surgery.3 Patients with BMI of 30kg/m² or higher with obesity-related comorbidities are potential candidates for adjustable gastric band only.3

Currently, SG is the most common procedure, accounting for approximately 53.8 percent of all bariatric procedures.4 It is a suitable option for high-risk patients, but it is irreversible and can cause gastroesophageal reflux.5 RYGB is the second-most common procedure, accounting for approximately 23.1 percent of all bariatric procedures.4 This procedure leads to rapid weight loss but can cause malabsorption, which can lead to vitamin deficiencies.5

AGB and BPD-DS are less commonly performed bariatric operations. The AGB is a reversible procedure. The band can be loosened or tightened by adding or removing saline from the port to achieve desired results. However, weight loss is achieved slower than SG and RYGB. The band also requires frequent adjustments and can slip.5 BPD-DS is a malabsorptive procedure that is less commonly performed in the United States.

Bariatric surgery is a well-established means of treating obesity; however, early readmission is a prevalent problem, with readmission rates ranging from 0.6 to 11.3 percent.2 A hospital readmission nearly triples the average 180-day cost of a bariatric operation.6 Nausea, vomiting, dehydration, and abdominal pain are the most common but preventable, causes of readmission after bariatric surgery.2,6–10 Understanding the underlying reasons for a patient’s readmission, associated factors, and current or future interventions might facilitate healthcare providers to target their efforts to reduce avoidable early readmission rates.2

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) and ASMBS11 combined their respective national bariatric surgery accreditation programs into a single unified program to achieve one national accreditation standard, the Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program (MBSAQIP).

Economic Burden Related to Readmissions

Readmissions are identified as an important quality metric for MBSAQIP. While MBSAQIP does have mechanisms in place to minimize under-reporting of readmissions, not every institution participates. In addition, not every insurer captures these data.10 Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) also tie reimbursement to readmissions through their Hospital Readmissions Reduction program, yet there is a paucity of strategies to prevent readmission.2,8 In 2011, 3.3 million adults were readmitted within 30 days, costing $41.3 billion.12 Medicare expenditures for potentially preventable readmissions are approximately $12 billion a year.13 It is estimated that 1 in 10 primary bariatric operations will result in an emergency room visit.10 Telem et al10 found that 17.5 percent of patients had more than one emergency department visit within 30 days, with a range of up to seven visitations in the 30-day period. It is evident that preventable readmissions cause an economic burden on patients, hospitals, and payers.

Factors Associated with Early Readmission

The likelihood of a patient being admitted after evaluation in the emergency department differed based on whether the patient presented to an index (i.e., the hospital where the patient had bariatric surgery) versus a nonindex hospital (i.e., a hospital other than where the patient had bariatric surgery). Patients were more likely to be admitted if they presented to their index hospital versus nonindex hospital.10 They pointed out that the accuracy of the reported readmission rates in studies are uncertain because the majority of studies center on single-institution experiences and do not capture patient admissions to nonindex hospitals.10

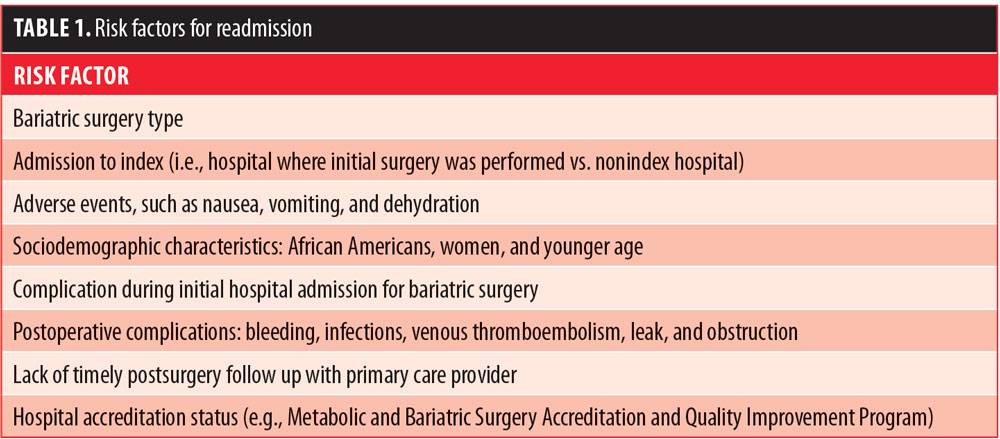

Table 1 outlines risk factors for readmission based on the available literature. First, the type of bariatric surgery selected is considered a risk factor for readmission. Studies consistently demonstrate that RYGB was associated with the greatest readmission rate, followed by SG, and then AGB.2,7,10,14

In addition to the type of bariatric procedure, a patient’s sociodemographic characteristics were associated with readmission; for example, African American patients were found to be at higher risk for readmission than other racial or ethnic groups.6,7,10 Female sex was significantly associated with unplanned readmission.14 Age was also identified as a risk factor for readmission.2 Older patients were found to have lower readmission rates indicating that there is the possibility of better coordination of care for older patients who might have established relationships with their primary care providers (PCPs).2 Therefore, it is suggested that healthcare providers should pay more attention to the younger patient population by providing closer postoperative follow-up.

Postoperative complications are also considered risk factors for readmission; having a complication during the initial hospital admission increases the risk for readmission.2,7,8 These patients would benefit from more vigilant postoperative monitoring. Bleeding,14–17 infections,14–17 venous thromboembolism,14–16 leak,15–17 and obstruction16,17 were identified as other reasons for readmission. Intervention strategies should be addressed to mitigate these complications. Recognizing these risk factors can enable healthcare professionals to provide closer postoperative follow-up to these higher risk patients.

Postoperative follow-up with PCPs might play a role in readmission. For example, patients who did not have timely postsurgery follow up with their PCPs had readmission rates 10 times higher than those who did.18 These findings indicate that healthcare providers should encourage their patients to follow up with their PCPs after their bariatric operation.

Hospital accreditation status also plays a role in readmission. Patients undergoing bariatric surgery at accredited centers were readmitted within 30 days of their procedure 3.4 to 7.6 percent of the time during the four years of the study compared to the nonaccredited program’s readmission rates of 8.3 to 16.5 percent annually.17

There are also conflicting views on whether factors, such as prolonged length of stay (LoS), high BMI classification, high American Society for Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status classification, and insurance type, are risk factors for readmission.2,6,8–10,14,16,17 The study conducted by Berger et al2 was the first to use MBSAQIP data registry and specifically report on “related” readmissions, therefore making it a more robust study. They concluded that BMI class, ASA class, and LoS did not have an association with readmission. However, the authors did not evaluate insurance type as a risk factor, which was a limitation of this study. Hong et al17 stated that patients who have publicly funded insurance were at risk for readmission. Conversely, Petrick et al9 concluded that payer status was not associated with an increased risk for readmission. Therefore, more studies examining the relationship between these factors and readmission are needed to guide healthcare professionals who work with patients who undergo bariatric surgery.

Current Interventions to Reduce Early Readmission Rates

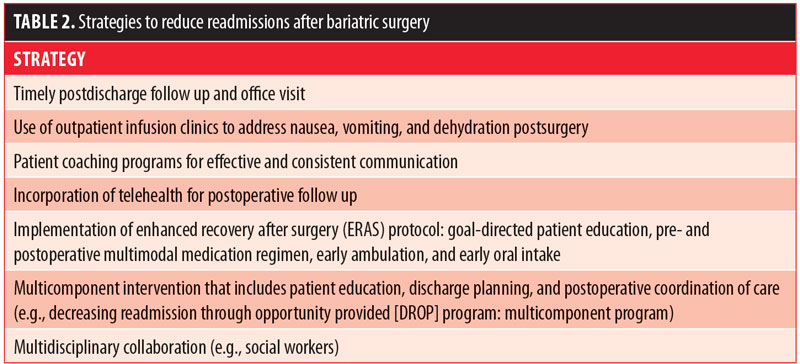

There were mixed findings on whether interventions to reduce early readmission rates were associated with follow-up time frame. Table 2 lists recommended strategies to reduce readmissions after bariatric surgery. Many studies have highlighted the importance of closer postoperative follow up, but the actual recommendations for close follow up varied across studies.2,6–10 A few studies revealed that timely postdischarge telephone follow up to supplement standard care effectively reduced early readmissions, and thus, provided a means of reducing costs.18,19 Several studies also suggested that timely outpatient follow up contributed to reduced readmission.18 However, the optimal frequency of postdischarge follow up also remains unknown. To date, healthcare providers are advised to take multiple factors into account when considering follow-up frequency, including type of bariatric surgery performed and severity of comorbidities.20

Providing an outpatient infusion clinic was shown to be an effective intervention to reduce early readmission rates related to nausea, vomiting, and dehydration.6–10 Increased access to outpatient and after-hours resources to ensure proper evaluation and mandated office-based hydration capability might limit the cost burden. Furthermore, validating and increasing postoperative surveillance in identified high-risk patient subsets could drastically reduce unplanned healthcare use.10

Multicomponent interventions were likely to reduce readmission rates significantly.21 For example, Stanford University’s 2008 pilot project on reducing readmissions evolved into the nationwide Decreasing Readmission through Opportunity Provided (DROP) program, which involved bundled processes aimed to reduce 30-day readmission rates nationwide by 20 percent. This project led Stanford’s bariatric program to reduce its readmission rates from 8 to 2.5 percent in four years.22 The DROP project focused on multicomponents, including patient education, discharge planning, and postoperative coordination of care.2,7,23 Hong et al17 support collaboration with social workers to coordinate the care of patients who have publicly funded insurance or are unemployed or disabled in an effort to reduce readmission rates.

Implementation of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocol has been effective to reduce complication rates in many disciplines, including colorectal, gastric, pancreatic, as well as in nongastrointestinal specialties.24 In a single-center based, retrosoective study, Lam et al25 evaluated an ERAS protocol comprising goal-directed patient education, pre- and postoperative multimodal medication regimen, early ambulation, and early oral intake. They found that although there was no significant difference in hospital readmission rates and postoperative complications between those in the ERAS group (n=130) and those who received standard care (n=84); LoS was significantly shorter in the ERAS group compared to the standard care group (1 vs. 2 days; p<0.001), and the ERAS group also had decreased median intraoperative opioid consumption and self-reported pain scores on Postoperative Day 1. It should be noted that this study was conducted in a single institution and a larger multi-institutional study is needed to determine if ERAS protocol has an impact on complication rates and/or early readmission rates.

Patient coaching programs have been shown to be effective in reducing early readmission after bariatric surgery. Jalilvand et al26 created a care coaching program for patients who undergo bariatric surgery to provide improved and more consistent communication with patients from the time of their initial hospital stay and discharge through to their first postoperative visit. Patients received a phone call at one, three, and seven days postdischarge by the care coach team. A specialized nursing team mitigated preventable causes of early postoperative readmissions, phone calls, and prolonged length of stay. Patients who received care coaching had reduced rates of intractable nausea and vomiting.26 Although a causal relationship between this program and decreased postoperative nausea or vomiting cannot be drawn due to its retrospective design, the results demonstrated the role of care coaches in providing consistent information to patients about controlling their symptoms through timely use of anti-emetic medication and measured oral intake.26 In contrary to this study, Macht et al23 found that bariatric coaching programs did not significantly reduce readmissions. Quality of patient education and strategies used to implement practices might be critical in the success of these types of interventions. Future efforts should focus on evaluating the patient’s understanding of educational practices.23

Studies showed the potential utility of telehealth to follow up on patients after bariatric surgery21 to reduce readmission. A study with telehealth in a large urban academic medical center found that the 30-day readmission rate was low.27 Additionally, it was found that telehealth visits improved access to care at high convenience and led to potential cost savings for surgical patients.27 Therefore, telehealth might be a suitable option for following up on patients after bariatric surgery.

Databases and Tools to Track Readmissions

There are several databases and tools that can be helpful in tracking readmissions and postoperative complications after bariatric surgery. For instance, New York State Department of Health, Statewide Planning and Research Cooperative System (SPARCS) is a database to capture unplanned emergency department visitation and readmissions, tracking data across all participating New York hospitals and facilities.10 Patients expected to be at a high risk based on the ACS National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) MORBPROB (estimated probability of morbidity) tool had a significantly higher rate of readmissions. It might be a useful tool to identify and target patients at risk for readmission.14 Bariatric Outcomes Longitudinal Database (BOLD) is the largest prospective database of bariatric patient outcomes worldwide; it can help identify predictors of serious postoperative complications requiring hospital readmission within 30 days of discharge.6 The database also captures surgeries performed by either a participant in the ASMBS designed Bariatric Surgery Centers of Excellence or by a fellow of the ASMBS. Healthcare professionals should familiarize themselves with the tools and databases that are available to them.

There is a dearth of studies that have evaluated national readmission rates for primary bariatric surgery with national, bariatric-specific data.2 Using the MBSAQIP database provides benefits of a large sample size and heterogeneity of practice type and volume, and thus, offers perhaps the best representation of bariatric surgery on a national level.4 However, MBSAQIP data registry measures 30-day outcomes from the operative date rather than discharge date, thus the definition of outcomes might differ from that used by Medicare. Additionally, identifying the causes of readmission is often challenging. Its multifactorial nature makes it difficult to isolate a single, definitive reason for readmission. If readmissions happen at a hospital other than MBSAQIP center in which the index procedure was done, it is difficult to capture those readmissions in this analysis. Data abstractors attempt to capture readmissions to any hospital; however, it might be more difficult to accurately identify readmissions to hospitals outside their own compared to payer-based databases.2

Conclusion

Developing innovative programs targeting high-risk patients could result in significant and achievable healthcare cost reduction.10 Given that nearly half of the early bariatric readmissions are due to preventable causes, close postoperative follow up might allow for early identification of high-risk patients. Then, healthcare providers can deliver appropriate interventions in a timely manner, potentially reducing avoidable readmission in patients who have bariatric surgery.

Multi-institutional studies with a large sample size are needed to further evaluate risk factors for readmission following bariatric surgery.28 Additionally, future studies are needed to assess whether some of the proposed interventions result in clinically meaningful improvement in the care of patients after bariatric surgery.

References

- Chen SY, Stem M, Schweitzer MA, et al. Assessment of postdischarge complications after bariatric surgery: a National Surgical Quality Improvement Program analysis. Surgery. 2015;158: 777–786.

- Berger ER, Huffman KM, Fraker T, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for bariatric surgery readmissions: findings from 130,007 admissions in the Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program. Ann Surg. 2018;267:122–131.

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (2016). Potential candidates for bariatric surgery. Available from: https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health- information/weight-management/bariatric-surgery/potential-candidates. Accessed February 27, 2019.

- Chaar ME, Lundberg P, Stoltzfus J. Thirty-day outcomes of sleeve gastrectomy versus Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: first report based on Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program database. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018;14:545–551.

- Gagnon L, Sheff E. Outcomes and complications after bariatric surgery. Am J Nurs. 2012;112:26–37.

- Dorman RB, Miller CJ, Leslie DB, et al. Risk for hospital readmission following bariatric surgery. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e32506.

- Aman MW, Stem M, Schweitzer MA, et al. Early hospital readmission after bariatric surgery. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:2231–2238.

- Doumouras AG, Saleh F, Hong D. 30-day readmission after bariatric surgery in a publicly funded regionalized center of excellence system. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:2066–2072.

- Petrick A, Brindle SA, Vogels E, et al. The readmission contradiction: toward clarifying common misconceptions about bariatric readmissions and quality improvement. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018;14:1026–1032.

- Telem DA, Yang J, Altieri M, et al. Rates and risk factors for unplanned emergency department utilization and hospital readmission following bariatric surgery. Ann Surg. 2016;263:956–960.

- American College of Surgeons & American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. (2017). Decreasing Readmissions through Opportunities Provided: Project summary [PDF]. Department of Gastrointestinal and Metabolic Surgery, NY Presbyterian Hospital – Cornell Campus, New York, NY.

- Chopra I, Wilkins TL, Sambamoorthi U. Hospital length of stay and all-cause 30-day readmissions among high-risk Medicaid beneficiaries. J Hosp Med. 2015;11:283–288.

- Costantino ME, Frey B, Hall B, Painter P. The influence of a postdischarge intervention on reducing hospital readmissions in a Medicare population. Popul Health Manag. 2013;16:310–316.

- Abraham CR, Werter CR, Ata A, et al. Predictors of hospital readmission after bariatric surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;221(1):220–227.

- Daigle CR, Brethauer SA, Tu C, et al. Which postoperative complications matter most after bariatric surgery? Prioritizing quality improvement efforts to improve national outcomes. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018;14:652–657.

- Garg T, Rosas U, Rogan D, et al. Characterizing readmissions after bariatric surgery. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;20:1797–1801.

- Hong B, Stanley E, Reinhardt S, et al. Factors associated with readmission after laparoscopic gastric bypass surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2012;8:691–695.

- Hudali T, Robinson R, Bhattarai M. Reducing 30-day rehospitalization rates using a transition of care clinic model in a single medical center. Adv Med. 2017:5132536.

- Harrison PL, Hara PA, Pope JE. The impact of postdischarge telephonic follow-up on hospital readmissions. Popul Health Manag. 2011;14:27–32.

- Mechanick JI, Youdim A, Jones DB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the perioperative nutritional, metabolic, and nonsurgical support of the bariatric surgery patient—2013 update. Obesity. 2013;21:S1–27.

- Kripalani S, Theobald CN, Anctil B, Vasilevskis EE. Reducing hospital readmission rates: current strategies and future directions. Annu Rev Med. 2013;65:471–485.

- Freeman GA. (2016). Reducing bariatric readmissions, HealthLeaders. https://www.healthleadersmedia.com/clinical-care/reducing-bariatric-readmissions. Accessed February 27, 2019.

- Macht R, Cassidy R, Cabral H, et al. Evaluating organizational factors associated with postoperative bariatric surgery readmissions. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13:1004–1009.

- Pędziwiatr M, Mavrikis J, Witowski J, et al. Current status of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocol in gastrointestinal surgery. Med Oncol. 2018;35.

- Lam J, Suzuki T, Bernstein D, et al. An ERAS protocol for bariatric surgery: Is it safe to discharge on post-operative Day 1? Surg Endosc. 2019;33(2):580–586.

- Jalilvand A, Suzo A, Hornor M, et al. Impact of care coaching on hospital length of stay, readmission rates, postdischarge phone calls, and patient satisfaction after bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12:1737–1745.

- Nandra K, Koenig G, DelMastro A, et al. Telehealth provides a comprehensive approach to the surgical patient. Am J Surg. 2018:1–4.

- Willson TD, Gomberawalla A, Mahoney K, Lutfi RE. Factors influencing 30-day emergency visits and readmissions after sleeve gastrectomy: results from a community bariatric center. Obes Surg. 2015;25:975–981.

Category: Past Articles, Review