When Endoscopic Therapies for Sleeve Leaks Fail: Safe Salvage Operations Including Esophagojejunostomy and Fistulajejunostomy

by Marc A. Ward, MD, FACS, FASMBS; Daniel G. Davis, DO, FACS, FASMBS; and Steven G. Leeds, FACS

Drs. Ward, Davis, and Leeds are with the Department of Minimally Invasive Surgery, Baylor University Medical Center in Dallas, Texas, and Texas A&M College of Medicine in College Station, Texas. Drs. Ward and Leeds are with the Center for Advanced Surgery, Baylor Scott and White Health in Dallas, Texas. Dr. Davis is with the Center for Metabolic and Weight Loss Surgery, Baylor Scott and White Health in Dallas, Texas.

Funding: No funding was provided for this article.

Disclosures: Steven G. Leeds is a consultant for Ethicon and Boston Scientific. Daniel G. Davis is a consultant for Intuitive. Marc A. Ward is a consultant for Boston Scientific.

Bariatric Times. 2022;19(6):14–15.

Abstract

Background: Sleeve gastrectomy is the most commonly performed bariatric surgery, and complications from staple line leaks occur in 1 to 3 percent of patients. Endoscopic management can avoid additional surgery by successfully healing the leak; however, in some cases, surgical intervention is required. Definitive surgical management is mainly accomplished with esophagojejunostomy (EJ) or fistulojejunostomy (FJ). Proceeding with surgical management of these leaks is poorly understood, given the rare need and high risk.

Methods: An institution-reviewed, board-approved, prospectively gathered database was used to identify patients undergoing definitive surgical management for bariatric surgery leaks with either an EJ or FJ. Initial data that led to the leak, intraoperative factors, and postoperative outcomes were collected.

Results: A total of 22 patients have undergone an EJ or FJ for definitive surgical management of a sleeve gastrectomy leak at our institution. Twelve patients underwent EJ, and 10 patients underwent FJ. There were six patients (27%) who had subsequent leaks after definitive surgery. Surgeries performed more than 90 days following the initial leak had a lower risk of subsequent leak at the definitive surgical operation. All subsequent leaks were healed with endoscopic therapy, and no further surgery was indicated. No deaths occurred.

Conclusion: Bariatric surgery leaks are difficult to manage. When endoscopic management fails, EJ and FJ are safe and feasible salvage options. Additional leaks following these salvage operations can occur in up to 27 percent of patients.

Keywords: Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy; esophagojejunostomy, fistulajejunostomy, anastomotic leak

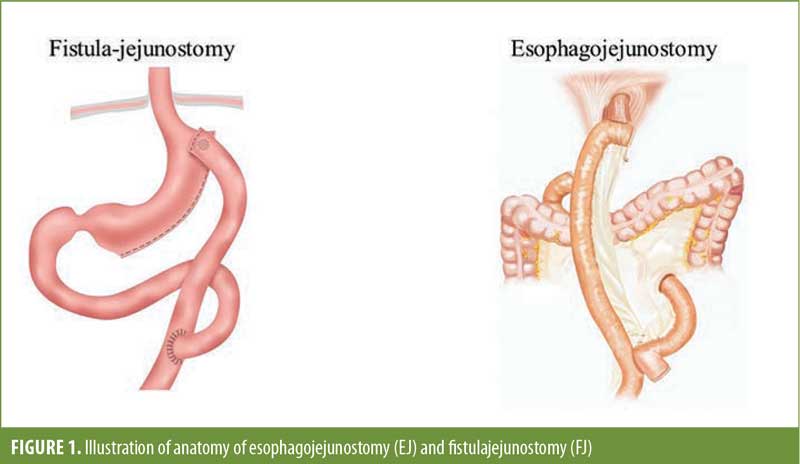

Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) has become the most common bariatric procedure performed since 2013.1 However, the growing popularity of this procedure has introduced the surgical community to a new set of complications that can be difficult to manage. These include gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), weight regain, dysphagia, and, probably the most worrisome, staple line leaks.2,3 The reported leak rate for LSG is about 1 to 3 percent,4–6 and with rising popularity and an increasing number of cases, leak management has become a significant concern and area of interest. The majority of the leaks occur at the top of the staple line near the angle of His. This is an area that is adjacent to the gastroesophageal junction and can be difficult to manage with endoscopic therapies. These endoscopic therapies have high rates of success, about 70 to 80 percent, and have been shown to limit morbidity compared to surgery.7,8 However, sometimes these therapies fail, and surgical intervention is required. Here, we discuss our experience with definitive surgical management of a sleeve leak by diversion of leak contents with either esophagojejunostomy (EJ) or fistulajejunostomy (FJ) (Figure 1).

Factors That Affect Endoscopic Management

There are several factors that play a role in the decision-making process for how to manage these patients. This patient population can present very differently than other patients, with the size of the leak, time to diagnosis, patient demographics, and location varying for each patient. The key to managing these patients is to choose the correct management plan, whether that is endoscopic therapy or surgery. Despite high rates of success with endoscopic therapy, it is important to determine if or when endoscopic management is futile and definitive surgery is more appropriate.

Recently, our group has developed a tool that can aid in predicting the success of endoscopic management in these patients. Although this study is currently in the peer review process, we identified four major factors that determine whether endoscopic therapy will fail. These factors include time to leak diagnosis, age, body mass index (BMI), and history of bariatric surgery. Our group has already shown that time to diagnosis and previous bariatric surgery are significant risk factors that might require these patients to have a definitive operation.9 When endoscopic management fails, surgical intervention is required.

Methods

We reviewed an institutional review board approved registry of all complications of the foregut from March 2013 to December 2020. There were 82 patients with leaks, and a total of 22 patients underwent EJ or FJ. A leak was defined as any instance where an anastomosis or transmural defect allowed luminal contents into the mediastinum or peritoneal cavity. This was identified on imaging, such as water-soluble contrast esophagram, upper gastrointestinal series, or computed tomography (CT) scan, or was found under direct visualization endoscopically. All 22 patients were transferred from other hospitals with intent to manage the leak. Demographics such as age, BMI, and sex were collected from all the patients. The sentinel operation that caused the leak was also identified. Patients were evaluated for postoperative healing of the leak, as well as postoperative complications.

Surgical intervention

Once the decision is made to proceed to the operating room for a contained leak, there are two options. The first option is washout and wide drainage to remove contaminated fluid and transform the leak site into a controlled fistula to the skin. Attempts can be made to surgically repair the leak at this time, but this often fails. The second option is definitive management with a gastrectomy and EJ or FJ with preservation of the continuity of sleeve anatomy. A conversion to a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) can also be considered if the leak is either in the mid or distal sleeve; however, this is rare, and the majority of sleeve leaks occur near at the proximal staple line near the gastroesophageal junction. In the case of an EJ, the gastric tube is typically deformed, causes the distal obstruction precipitating the LSG leak, and will continue its presence. In the case of an FJ, the leak site is amenable with an enteric drainage procedure. This will preserve the normal anatomy and allow for continued and desired weight loss.10,11 The decision between the two procedures needs to be done by an experienced surgeon due to the technical complexity, as well as the postoperative management.

Technique in Brief

Hiatal dissection. Both an EJ and FJ require a complete hiatal dissection to adequately mobilize the site of the perforation. Both robotic and laparoscopic platforms have been used during these operations at the preference of the operating surgeon. The expectation should be for a significant amount of adhesive disease in the left upper quadrant, and this needs to be navigated carefully. The bulk of the adhesive disease will be at the left crus, with extension to the spleen and posterior into the lesser sac. A complete mediastinal dissection should be performed to reduce the gastroesophageal junction below the hiatus to minimize tension on the new anastomosis. Frequent evaluation with endoscopy can assist in navigating this area by confirming anatomy in areas where it is obscured from gross contamination and adhesive disease.

Roux limb. Creation of the Roux limb will be required in both operations. The length of the biliopancreatic and Roux limbs can vary, but it must be long enough to avoid putting unneeded tension on the new anastomosis. Typically, our biliopancreatic limb measures about 50 to 70cm and the Roux limb measures about 70 to 100cm. The jejunojejunostomy is performed in a side-to-side fashion using a 60mm stapler. The mesenteric defects are closed with a nonabsorbable barbed 3-0 suture.

Esophagojejunostomy. Once the hiatal dissection is complete, a staple load is used to transect the esophagus just above the gastroesophageal junction. Endoscopy is useful to identify the exact location if needed. The middle of the sleeve is transected with the same staple load to include the perforation and affected site. The left gastric artery arcade is then transected immediately adjacent to the lesser curvature with a vascular stapler or clips. The proximal sleeve is then removed from the peritoneal cavity. A 25mm circular stapler or a two-layer, handsewn anastomosis using 3-0 barbed suture or 3-0 running polydioxanone (PDS) suture can then be performed. Upper endoscopy is used at this time to do a leak test and examine the anastomosis.

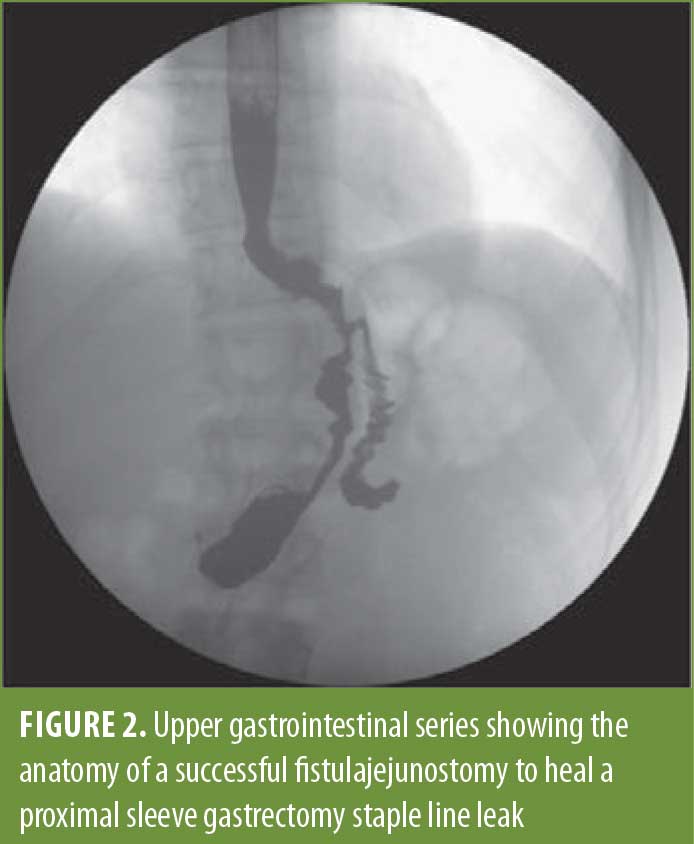

Fistulojejunostomy. The appearance of the perforation dictates when we perform an FJ. In cases where mobilization is difficult, this might be a better and safer option than the EJ. The perforation site is always larger than anticipated in this procedure, and the prior sleeve anatomy makes it difficult to perform a stapled anastomosis at this location. A two-layered, handsewn anastomosis is created using the same sutures as above. The endoscope is used as a bougie to make sure the connection is not too small and can also be used to perform a leak test once the anastomosis is complete. An upper gastrointestinal series of an FJ is shown in Figure 2.

Surgical Outcomes

We have performed more than 20 EJs and FJs for sleeve gastrectomy leaks at our institution. The majority of these patients had some endoscopic therapy prior to surgery, but some patients required immediate surgery due to gross contamination and hemodynamic instability. A total of 27 percent of patients had a leak following definitive surgical management with either procedure; 17 percent leaked following EJ, and 40 percent leaked following FJ. All of these leaks were healed with endoscopic interventions, and there were no deaths as a result of the leaks.

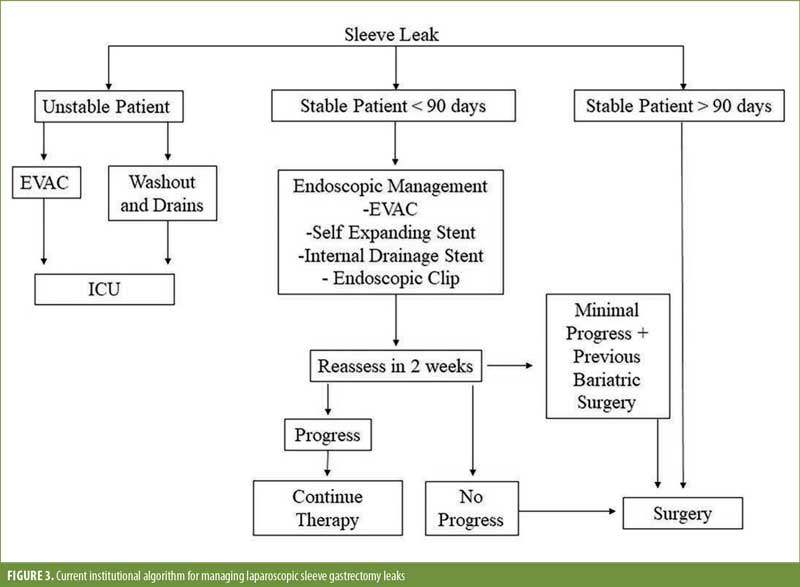

Interestingly, our data show that the likelihood an EJ or FJ leak decreases as the leak becomes more chronic. This is contrary to the data supporting the use of endoscopic therapy, where the earlier you intervene the better chance you have of endoscopic success. With surgical intervention, it appears that after 90 days following the initial leak, the leak rate following a definitive diversion procedure will decrease and plateau. This would explain why the FJ patients had a higher leak rate, as these patients were more often done earlier than 90 days. We typically use FJ as an earlier surgical intervention before chronic indurated tissue develops. We previously published an algorithm regarding our management of sleeve leaks, where leaks persisting for more than 90 days would more often benefit from definitive surgery, compared to endoscopic therapies (Figure 3).9 In addition, by waiting more than 90 days, the success of the EJ or FJ is higher, likely due to a reduction in tissue inflammation and infected material.

Conclusion

Although endoscopic therapies are successful 70 to 80 percent of the time, sometimes they fail. When endoscopic therapies fail, there needs to be a definitive surgical option available. Both EJ and FJ are safe salvage operations for these complex patients. Despite a subsequent leak rate of 27 percent after EJ and FJ, all these patients were healed using endoscopic methods following these operations. As a result, we recommend that any facility performing these operations needs to also be able to manage leaks endoscopically. When managing sleeve leaks, it is our recommendation to manage these endoscopically early in their progression, but as the leak becomes more chronic, definitive surgical management is safe and effective.

References

- Khorgami Z, Shoar S, Andalib A, et al. Trends in utilization of bariatric surgery, 2010–2014: sleeve gastrectomy dominates. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13(5):774–778.

- Clapp B, Wynn M, Martyn C, et al. Long term (7 or more years) outcomes of the sleeve gastrectomy: a meta-analysis. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018;14(6):741–747.

- Genco A, Soricelli E, Casella G, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux disease and Barrett’s esophagus after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: a possible, underestimated long-term complication. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13(4):568–574.

- Gagner M, Hutchinson C, Rosenthal R. Fifth International Consensus Conference: current status of sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12(4):750–756.

- Rosenthal RJ; International Sleeve Gastrectomy Expert Panel, Diaz AA, et al. International Sleeve Gastrectomy Expert Panel Consensus Statement: best practice guidelines based on experience of >12,000 cases. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2012;8(1):8–19.

- Knapps J, Ghanem M, Clements J, Merchant AM. A systematic review of staple-line reinforcement in laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. JSLS. 2013;17(3):390–399.

- Rogalski P, Swidnicka-Siergiejko A, Wasielica-Berger J, et al. Endoscopic management of leaks and fistulas after bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 2021;35(3):1067–1087.

- Smith ZL, Park KH, Llano EM, et al. Outcomes of endoscopic treatment of leaks and fistulae after sleeve gastrectomy: results from a large multicenter US cohort. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2019;15(6):850–855.

- Ward MA, Ebrahim A, Clothier JS, et al. Factors that promote successful endoscopic management of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy leaks. Surg Endosc. 2021;35(8):4638–4643.

- Chouillard E, Chahine E, Schoucair N, et al. Roux-en-Y fistulo-jejunostomy as a salvage procedure in patients with post-sleeve gastrectomy fistula: mid-term results. Surg Endosc. 2016;30(10):4200–4204.

- Szymanski K, Ontiveros E, Burdick JS, et al. Endolumenal vacuum therapy and fistulojejunostomy in the management of sleeve gastrectomy staple line leaks. Case Rep Surg. 2018;2018:2494069.

Category: Past Articles, Review