Raising the Standard: Bariatric Surgery in the Time of a COVID-19 Pandemic

by ANTHONY T. PETRICK, MD, FACS, FASMBS; DOMINICK GADALETA, MD, FACS, FASMBS; and JOHN M. MORTON, MD, MPH, MHA, FACS, FASMBS, ABOM

by ANTHONY T. PETRICK, MD, FACS, FASMBS; DOMINICK GADALETA, MD, FACS, FASMBS; and JOHN M. MORTON, MD, MPH, MHA, FACS, FASMBS, ABOM

Dr. Petrick is Quality Director, Geisinger Surgical Institute; Director of Bariatric and Foregut Surgery, Geisinger Health System, Danville, Pennsylvania. Dr. Gadaleta is Chair, Department of Surgery, Southside Hospital; Director, Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery, North Shore University Hospital, Northwell Health, Manhasset, New York; Associate Professor of Surgery, Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell, Hempstead, New York. Dr. Morton is Vice-Chair of Quality and Division Chief of Bariatric and Minimally Invasive Surgery in the Department of Surgery at Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut.

FUNDING: No funding was provided for this article.

DISCLOSURES: The authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Bariatric Times. 2020;17(4):18–19

“…we must have a citizenship less concerned about what the government can do for it and more anxious about what it can do for the nation.”

–Warren G. Harding

While many are familiar with John F. Kennedy’s variation of this quote, we chose to start with Harding’s speech from the Republican National Convention in June 1916 as a small reminder of facts we all take for granted. Since publication of our last column, the United States (US) healthcare system has been cast into turmoil on a scale inconceivable just a month before. Our columns are written about one month ahead of print. As of mid-February 2020, the COVID-19 virus was largely confined to mainland China (>70,000 cases) with less than 1,000 cases worldwide. As of March 26, there are over 500,000 cases worldwide and over 75,000 cases in the US.¹ Understanding that these statistics will be of only historical interest by the time the column is published, our objective this month is to provide tools to evaluate the place of bariatric surgery in our rapidly changing healthcare environment.

We have all come to understand the term “flattening the curve” and its importance in permitting our healthcare system to maintain facilities, providers, and supplies to care for patients with COVID-19. However, as we think about the stress the COVID-19 pandemic has placed on the US healthcare system, it is important to understand that the stress has not and will not impact all portions of the country uniformly. Currently, and for the foreseeable future, hospitals in New York City are in crisis facing shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE), providers, and hospital beds, while states with low population density have experienced proportionately fewer cases.

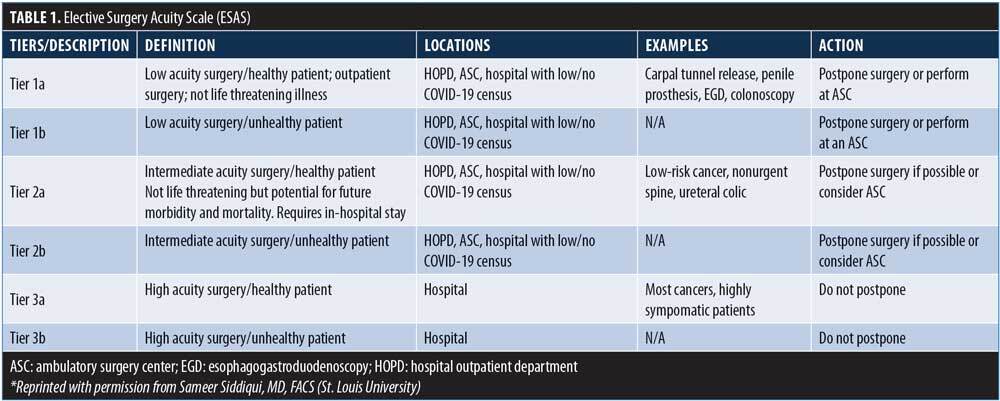

However, the definition of “elective” remains elusive and is different in relatively unaffected areas compared to urban population centers. While ESAS represents a comprehensive tool for assessment of case acuity, it falls short for bariatric as well as other interventional procedures. At Geisinger Health System, the risk-benefit analysis has changed daily. On March 15, we had no COVID-19 cases in our health system. We had beds, providers and a tenuous but reliable PPE supply chain. There were no community COVID-19 cases, and our plan was to continue with elective surgery. We identified critical benchmarks for reassessment of this strategy. These included: 1) first case in the community, 2) first case in our hospitals, 3) first community acquired case, 4) surge in community, and 5) surge in hospitals. While we were not able to develop a specific action plan for any combination of these events, we had a COVID Preparedness Leadership Team that met at least daily with “elective” procedures as a standing agenda item. We adopted a three-tier designation to interventional procedures.

Tier I. Easily identifiable elective procedures with no threat of progressive clinical impact

Tier II. Progressive threat to life and limb or threat of progressive clinical deterioration. These cases fall into the difficult decision tree for “elective” surgery.

Tier III. Immediate threat to life and limb. These cases would not be affected by restricting procedures

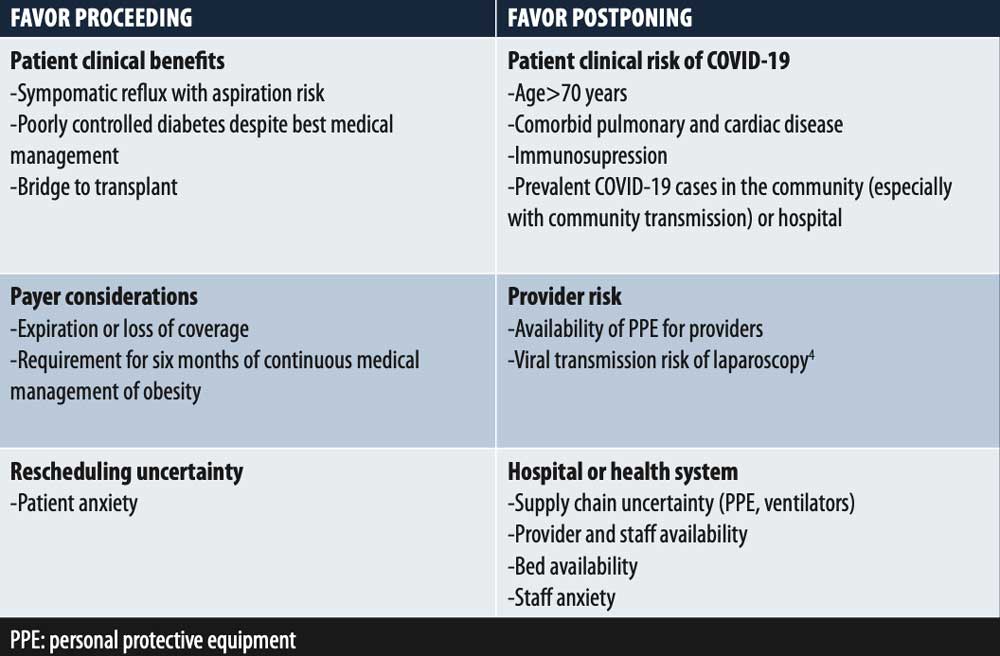

As COVID-19 cases mounted, many hospitals viewed bariatric surgery as a Tier I procedure. However, we made a case that many bariatric patients were actually Tier II patients. Unfortunately, significant obesity bias has been expressed by both administrators and other providers as these discussions progressed in different centers. In light of these issues, a partial list of factors to consider when assessing the acuity of bariatric cases is presented in Table 2.

On March 16, we admitted our first two COVID-19 patients to intensive care units (ICUs) in our health system. Providers with potential exposure were quarantined. We also identified a supply trajectory that both Level 3 face shield and N95 masks were at risk to be exhausted prior to our resupply schedule. There was also uncertainty as to what proportion of our PPE orders would be delivered. On March 17, we had a provider test positive and quarantined additional providers. The decision to postpone“elective”surgery was made at this time. All surgical procedures were reviewed by the charge anesthesiologist and the Chief Quality Officer. At that time we canceled several, but elected to perform two bariatric procedures, including a patient with expiring insurance and a patient awaiting listing for liver transplant. While our community and hospital census of COVID-19 infected patients remains low, our supply chain has continued to deteriorate and staff anxiety has risen. Our definition of “elective” has broadened as the factors favoring postponement have increased.

TABLE 2. Factors to consider for “elective” bariatric surgery

The Northwell Health (NWH) experience as a whole mirrored other urban and suburban health systems, which eliminated all but Tier III procedures early on in the process. Although areas across the country with lower population density and fewer or no COVID-19 cases were continuing to perform “elective” surgery, in an effort to provide material and personnel support, all hospitals at NWH were held to the same standard. For those still trying to prioritize, Table 2 can provide a framework for these centers to perform a risk–benefit analysis for bariatric patients. Specific considerations include the recognition that these centers might have a brief window of opportunity for their bariatric patients as the pandemic progresses. Providers should evaluate the risk to payer benefits due to the shutdown of “nonessential” businesses in many areas. The loosening of restrictions and reimbursement for telehealth provide an opportunity for continuous management of patients whose bariatric procedures are delayed. Finally, providers must consider the regional and national impact of utilizing PPE supplies for bariatric surgery.

A determination to proceed with bariatric surgery is straightforward in some patients, but case triage should avoid blanket policies. Providers must remember that COVID-19 is one of many competing risks for our surgical patients.4 We remain acutely aware that publishing a column in a time of such rapid change in both our health care and personal priorities is destined to be quickly outdated. Our hope is that many bariatric centers will be able to use this information to prioritize their bariatric surgical procedures when the crisis ends. Better yet, it would be great if centers were positioned to use this framework to ramp up “elective”bariatric surgery in a time when the restrictions are lifted. We cannot know the future; however, as Abraham Lincoln said, “The best way to predict the future is to create it.”As a community of healthcare providers and citizens, let’s work together to create the better future.

Editor’s Note

by JOHN M. MORTON, MD, MPH, MHA, FACS, FASMBS, ABOM

Dr. Morton is Vice-Chair of Quality and Division Chief of Bariatric and Minimally Invasive Surgery in the Department of Surgery at Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut.

These are unprecedented times. As expressed here, surgeons are natural team leaders and well poised to meet challenges. Surgeons are often at the intersection of the microbial and human worlds—it is no different now. Please read my editorial the single experience of bariatric surgery emergency (see below). At Yale Bariatrics, we also cancelled elective bariatric surgery and confined our interventions to emergency cases such as internal hernias. Additionally, we moved over 500 in-person clinic visits to teleheath and performed our informational seminar and preoperative online. Time will tell what the new normal will be, but I do know that surgeons will be there—ready, willing, and able to care for our patients in need.

REFERENCES

- Coronavirus COVID-19 Global Cases by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU). https://coronavirus.jhu. edu/map.html. Accessed March 22, 2020.

- COVID-19: Guidance for Triage of Non-Emergent Surgical Procedures. American College of Surgeons. https://www.facs.org/about-acs/covid-19/ information-for-surgeons/triage. Accessed March 20, 2020.

- Alp E, Bijl D, Bleichrodt RP, et al. Surgical smoke and infection control. J Hosp Infect. 2006;62(1):1–5. Epub 2005 Jul 5.

- Miller J. SAGES Recommendations Regarding Surgical Response to COVID-19 Crisis. SAGES. https://www.sages.org/recommendations-surgical- response-covid-19/. Accessed March 20, 2020.

Category: Past Articles, Raising the Standard