Jejunal Interposition as a Definitive Treatment for Gastric Fistula after Sleeve Gastrectomy

by Luis Fernando Zorrilla Núñez, MD; Pablo Gerardo Zorrilla Blanco, MD; Noé Núñez Jasso, MD; and Álvaro Tristán Peralta, MD

Luis Fernando Zorrilla Núñez, MD; Pablo Gerardo Zorrilla Blanco, MD; Noé Núñez Jasso, MD; and Álvaro Tristán Peralta, MD, are from University Hospital, Autonomous University of Nuevo Leon, Mexico.

Funding: No funding was provided.

Disclosures: The authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this manuscript.

Abstract: Although the available literature describes treatment of gastric fistula post-laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, no one approach has been proven to be superior. The authors present two cases of two patients who experienced fistula secondary to laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy in which conservative treatment failed. Both patients were treated with jejunal interposition, which is conversion to a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass with an interposed jejunal loop. Both patients had good results, tolerating oral feeding with no evidence of the fistula using contrast media in the postoperative period. They concluded that in cases where conservative treatment fails, conversion to Roux-en-Y gastric bypass with an interposed jejunal loop, may be considered.

Bariatric Times. 2017;14(9):18–20.

Introduction

The global epidemic of obesity has given rise to available therapies in which to treat the disease, including pharmacotherapy, endoscopic devices and procedure, and metabolic and weight loss surgeries. Currently, the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) and sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) are the two most commonly performed bariatric operations worldwide, and LSG continues to grow in popularity among the surgical community.[1] In the United States, the proportion of LSG procedures increased from 17.8 percent in 2011 to 53.8 percent in 2015.[2,3] Though RYGB procedures have declined, it remains the gold standard.[2]

Leakage from the staple line is among the most feared complications of LSG, likely because of the complexity in diagnosing and treating leaks. Recent studies report leak rate incidence after LSG up to three percent.[4]

Multiple efforts, including stent usage, have been proposed to avoid re-intervention in patients with a post-gastric sleeve fistula with encouraging results,[5] however this conservative treatment has failed in a considerable number of patients.[6] Patients who fail conservative treatment require reoperation. The current consensus states that Roux-en-Y reconstruction is a valid and effective treatment option for leaks, yet it should always be considered last.[5] Other laparoscopic treatment options described in the literature include the following: fistulo-jejuno anastomosis, conversion to bypass with fistulo-jejuno anastomosis, and total gastrectomy with esophageal-jejuno anastomosis.[7]

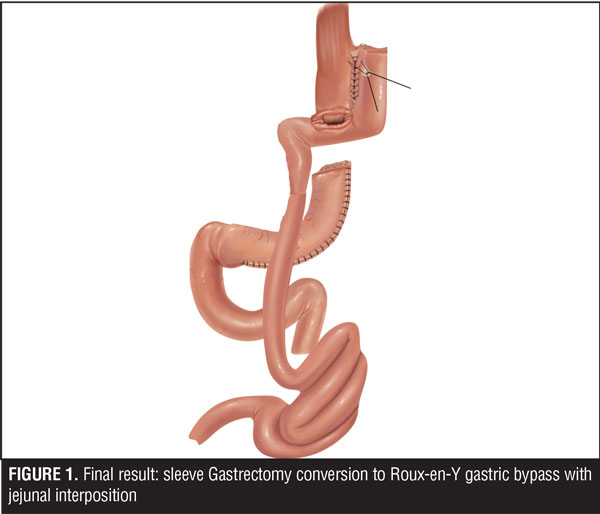

Here, the authors report the cases of two patients who experienced fistula secondary to LSG in which conservative treatment failed. Both patients were treated with jejunal interposition, which is conversion to a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass with an interposed jejunal loop (Figure 1).

Case 1

A 30-year-old woman with a history of overweight (body mass index [BMI] 28kg/m2 at time of presentation) underwent an LSG operation at an outside facility. Three weeks postoperative, she presented with generalized peritonitis secondary to a leak from the LSG. She underwent re-operation laparoscopically; peritoneal lavage was performed, drains were placed, and enteral access was achieved with the naso-jejunal catheter. Broad spectrum antibiotics and enteral feed were initiated and the patient was referred to the authors’ facility.

After resolving the acute stage, upper endoscopy was performed, and an opening 1cm in diameter was found in the proximal stomach; stenosis of the trajectory of the gastric sleeve was found. A metallic prosthesis 15cm x 23mm in diameter was placed as conservative treatment; however, due to poor tolerance it was removed three weeks later. The patient continued with purulent secretion through the intra-abdominal drain, feeding through a naso-jejunal catheter, and with broad-spectrum antibiotics.

Four months after conservative treatment was started and because of radiologic evidence of fistula persistence, the care team decided on a definitive surgical treatment plan that included diagnostic laparoscopy, primary closure of the fistula, and conversion to gastric bypass versus total gastrectomy with an esophago-jejuno anastomosis. At the time of re-operation, the patient’s BMI was 23kg/m2.

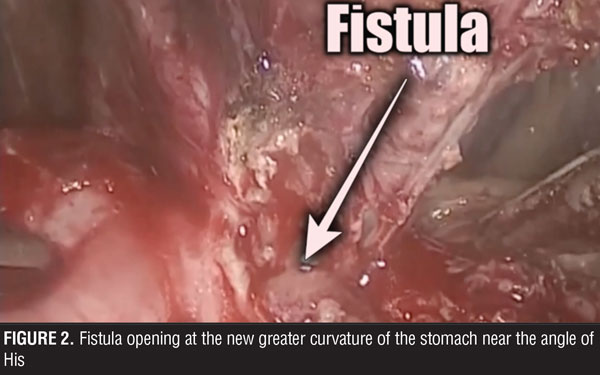

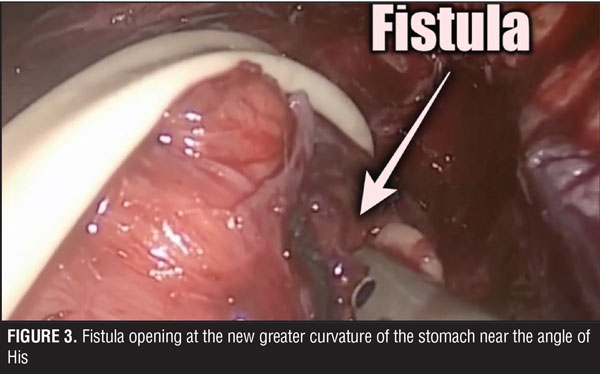

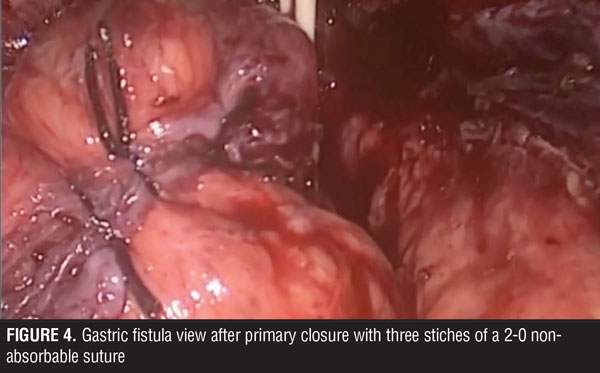

The surgical team performed the procedure laparoscopically, and accessed the abdominal cavity using the open Hasson technique. The rest of the trocars were located in the upper abdomen, supra-umbilical, and below both costal margins. During surgery, multiple adhesions were found in the abdominal cavity surrounding the stomach. These were dissected and the trajectory of the fistula was followed up to its origin close to the angle of His (Figures 2 and 3). Primary closure of the fistula was performed with three stiches of a 2-0 non-absorbable suture (Figure 4). Later, a gastric pouch of approximately 15mL was created with a lineal stapler to convert to gastric bypass.

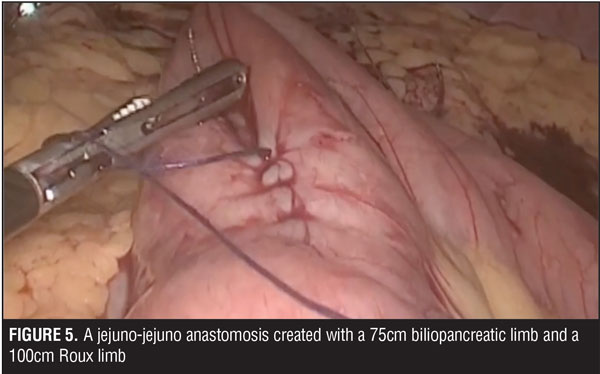

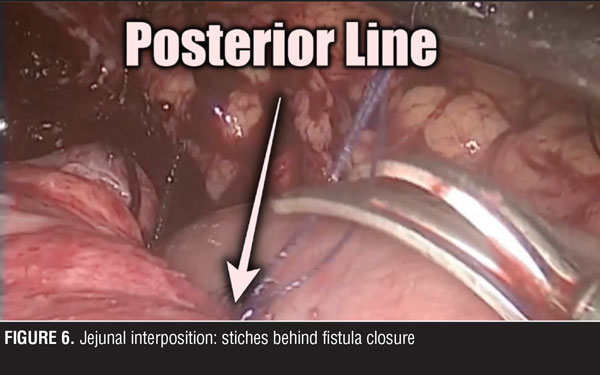

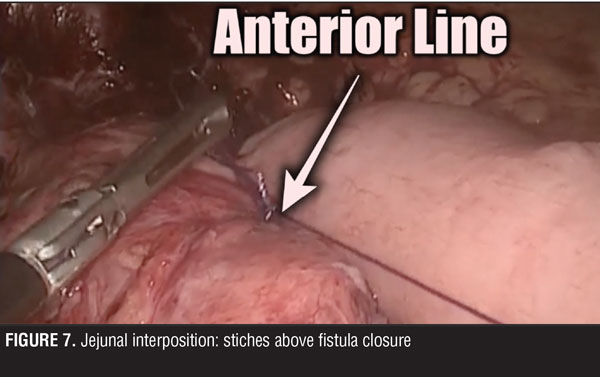

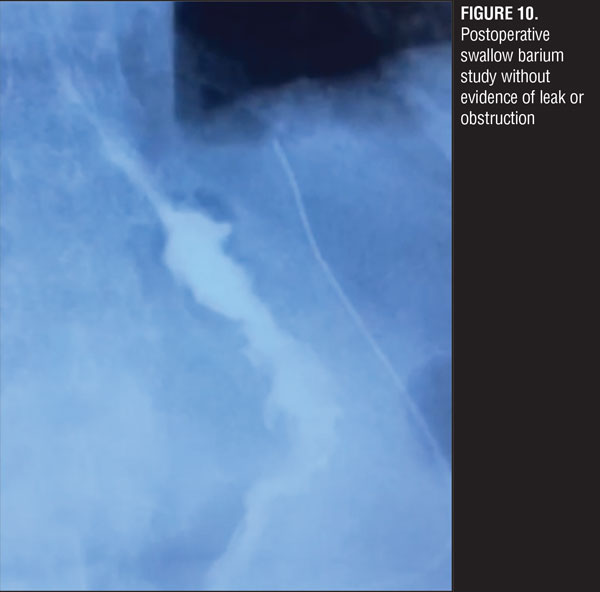

A jejuno-jejuno anastomosis was created with a 75cm biliopancreatic limb and a 100cm Roux limb (Figure 5). Afterwards, the Roux limb was placed over the fistula as an interposed segment, fixing it to the anterior and posterior part of the fistula with PDS 00 (polydioxanone) sutures, creating a serosal patch (Figures 6 and 7). To finalize, an end-to-side gastro-jejuno anastomosis was manually created with 00 absorbable sutures (Figure 8). With this, pressure to the fistula was released and closure was achieved with the help of the serosal patch of the Roux limb. The patient had a good evolution, tolerating oral feeding with no evidence of the fistula using contrast media in the postoperative period (Figures 9 and 10).

Case 2

A 51-year-old female patient presented to the authors’ facility. Prior to presentation she underwent a laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (LAGB) procedure more than 10 years prior to presentation that was complicated by erosion. She had the band removed by laparoscopy, and then underwent laparoscopic gastric plication. Weight loss results following this procedure were unsuccessful. She then underwent a conversion procedure to convert the plication to a LSG. She developed a leak in postoperative period for which conservative management was not successful. The leak continued with the left pleura developing an empyema treated by thoracotomy and inferior left lobectomy. The gastric leak converted into a gastro-pleuro-cutaneus fistula.

At the time of presentation to the authors’ facility, the patient had been living with the fistula for one year. Her BMI was 22kg/m2. The authors’ prepared the patient for surgical treatment with nutrition by a naso-jejunal catheter for six weeks. At the time of surgery, after adequate nutrition, the patient’s BMI was 25kg/m2. They decided to convert the LSG to RYGB with an interposed jejunal bowel as a serosal path.

The surgical team found multiple adhesions between the stomach and the liver. After a thorough dissection, they located the fistula at the angle of His of the Stomach (2cm). There was bleeding near the spleen, so the surgical team converted to a laparotomy in order to control the bleed. After that, they continued the surgery in the open approach.

Primary closure of the fistula was performed with three stiches of a 2-0 non-absorbable suture; later a gastric pouch of approximately 15mL was created with a lineal stapler to convert to RYGB. A jejuno-jejuno anastomosis was created with a 75cm biliopancreatic limb and a 100cm Roux limb. The Roux limb was placed over the fistula as an interposed segment, fixing it to the anterior and posterior part of the fistula with 2-0 non-absorbable suture, creating a serosal patch. To finalize, an end-to-side gastro-jejuno anastomosis was manually created with 00 absorbable suture.

With this, pressure to the fistula was released and closure was achieved with the help of the serosal patch of the Roux limb. The patient had a good evolution, tolerating oral feeding with no evidence of the fistula using contrast media in the postoperative period.

Discussion

One critical step in performing the RYGB is the creation of the gastric pouch along with the gastro-jejuno anastomosis. Complications of the gastric pouch, such as leaks, stenosis of the anastomosis, and marginal ulcers with bleeding, seem to be related to staple line disruption and the formation of fistulas between the gastric pouch and the excluded stomach.[8]

Capella et al and Fobi et al[9–11] have recommended gastric bypass techniques that interpose a segment of jejunum between the gastric reservoir and the excluded stomach. This works as a patch and prevents fistulas occurring between these two structures. It is important to note that the jejunal interposition is a safeguard that minimizes the recurrence of leak, but is not the reason for the healing of the fistula; placement of the stitches to close the fistula and converting to a gastric bypass reduced the pressure in the pouch that resulted in the healing.

Capella et al[10] reported good results with interposition among 652 consecutive patients (average BMI 50kg/m2 [range: 38–86kg/m2] with no previous bariatric surgical history who underwent RYGB using this technique. In this retrospective analysis, they found, at five years postoperative, no incidences of fistula. Early reoperation rate was 0.5 percent and the incidence of late complications that required reoperation was 0.5 percent. At five years, the patients average BMI was reduced to 29kg/m2 [range: 20–43kg/m2], and 93 percent of patients lost more than 50 percent excess weight.

The authors have reported their experience with this technique, demonstrating a reduction in postoperative complications.[12] Although the available literature describes treatment of gastric fistula post-LSG, no one approach has been proved to be superior. In the cases presented herein, the authors applied the same methods described by Capella et al and Fobi and Lee, and obtained successful results.

Although the authors believe that the best way to treat a complication is with a good surgical technique to avoid its appearance, they acknowledge the importance and need of prospective studies that demonstrate the effectiveness of treatments, such as jejunal interposition, when complications occur.

Conclusion

Given the rise in popularity of the LSG procedure worldwide, surgical teams must prepare for possible complications in the postoperative period. Gastric fistula, though not the most common complication of LSG, has many treatments described in the literature, from conservative to more aggressive.

The authors still believe that the treatment for a gastric fistula should start with the less aggressive option and give the patient the opportunity to heal without re-intervention. In cases where this approach fails, conversion to RYGB with an interposed jejunal loop, may be considered.

References

- Angrisani L, Santonicola A, Iovino P, et al. Erratum to: Bariatric surgery and endoluminal procedures: IFSO Worldwide Survey 2014. Obes Surg. 2017;27(9):2290–2292.

- American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. Estimate of Bariatric Surgery Numbers, 2011-2015. https://asmbs.org/resources/estimate-of-bariatric-surgery-numbers. Accessed June 8, 2017.

- Abraham A, Ikramuddin S, Jahansouz C, et al. Trends in bariatric surgery: procedure selection, revisional surgeries, and readmissions. Obes Surg. 2016;26(7):1371–1377.

- Abou Rached A, Basile M, El Masri H. Gastric leaks post sleeve gastrectomy: Review of its prevention and management. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(38):13904–13910.

- Rosenthal RJ. International Sleeve gastrectomy expert panel consensus statement: best practice guidelines based on experience of more than 12,000 cases. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2012;8(1):8–19

- El Mourad H, Himpens J, Verhufstadt J. Stent treatment for fistula after obesity surgery: results in 47 consecutive patients. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:808–816

- van de Vrande S, Himpens J, El Mourad H, Debaerdemaeker R, Leman G. Management of chronic proximal fistulas after sleeve gastrectomy by laparoscopic Roux-limb placement. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2013;9(6):856–861.

- Byrne TK. Complications of surgery for obesity. Surg Clin North Am. 2001;81:1181e93.

- Capella JF, Capella RF. Gastro-gastric fistulas and marginal ulcers in gastric bypass procedures for weight reduction. Obes Surg. 1999;9:22–27

- Capella JF, Capella RF. An assessment of vertical banded gastroplasty-Roux- en-Y gastric bypass for the treatment of morbid obesity. Am J Surg. 2002;183(2):117–123.

- Fobi MAL, Lee H. The surgical technique of the Fobi-Pouch operation for obesity (the transected silastic vertical gastric bypass). Obes Surg. 1998;8(3):283–288.

- Zorrilla PG, Salinas RJ, Salinas-Martinez AM. Vertical banded gastroplasty-gastric bypass with and without the interposition of jejunum: preliminary report. Obes Surg. 1999;9(1):29–32.

Category: Case Series, Past Articles