Leaks and Single Anastomosis Duodenoileal Bypass with Sleeve Gastrectomy (SADI)

by Paul E. Enochs, MD, FACS, FASMBS

by Paul E. Enochs, MD, FACS, FASMBS

Dr. Enochs is with WakeMed Bariatric Specialists of NC in Cary, North Carolina.

Funding: No funding was provided.

Disclosures: The author has no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Abstract: The single anastomosis duodenoileal bypass with sleeve gastrectomy (SADI) is the latest surgical procedure that has been approved by the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) and the International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders (IFSO) for use on patients who undergo bariatric surgery. Now that this procedure has garnered approval and acceptance, there will likely be an increase in the number of these procedures performed. Historically, the traditional duodenal switch procedure has been less than one percent of all the bariatric procedures done nationwide. Since SADI is a variant of this traditional procedure, the duodenal anastomosis that is part of both of these procedures might be a new concept for many bariatric surgeons. As a result, the prevention and management of these potentially life-threatening complications is one in which all bariatric surgeons should be well versed.

Keywords: SADI, bariatric, surgery, leak, complications

Bariatric Times. 2020;17(6):20–21

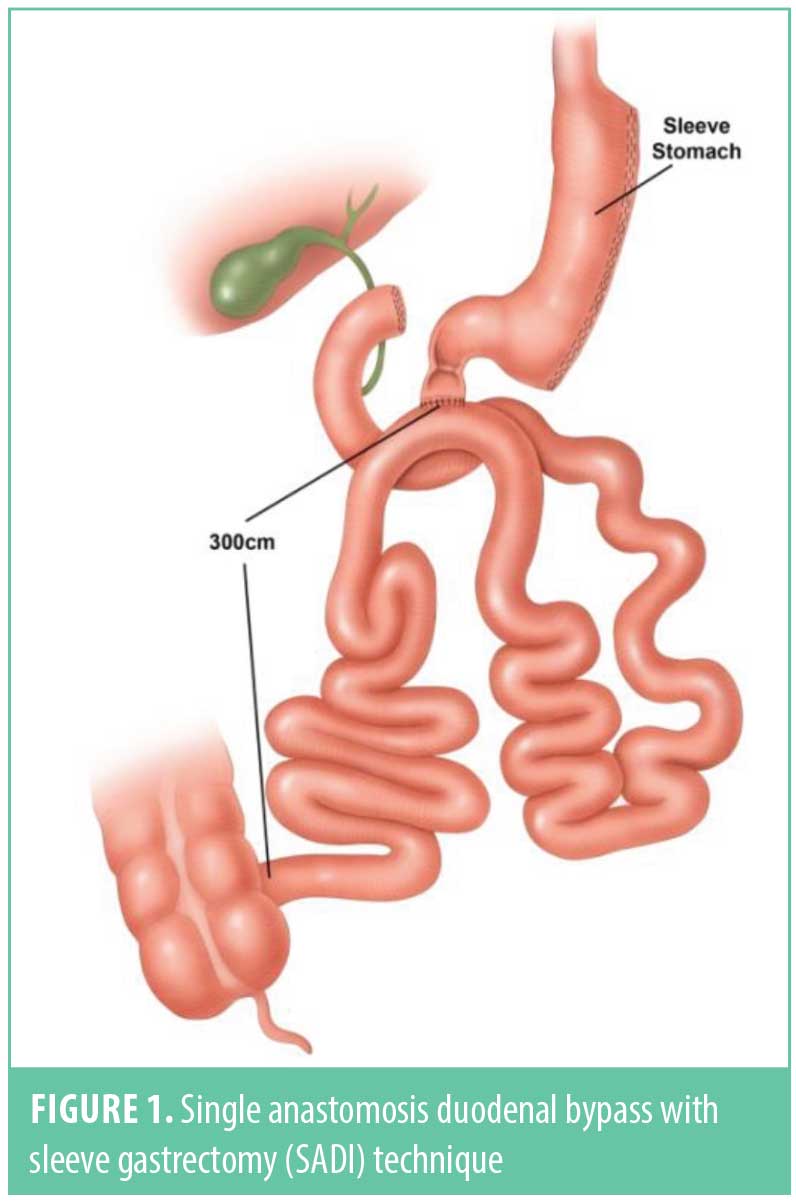

The sleeve gastrectomy (SG) and the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) are currently the two most common weight loss surgery procedures performed in the United States (US).1 Yet, it has long been determined that procedures with increased malabsorption, such as the biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch, can aid in greater weight loss and metabolic improvement in patients with morbid obesity, especially those with a higher body mass index (e.g., >50kg/m2).2 Since these procedures have ultimately had a greater operative risk profile and perceived technical difficulty than either the SG or RYGB, the traditional duodenal switch, until recently, has been relegated to less than one percent of the procedures performed nationwide. In an attempt to simplify the technique of the duodenal switch, but still maintain the principles of a malabsorptive procedure, Torres et al (Figure 1) introduced the single anastomosis duodenoileal bypass with SG (SADI) technique.3 Their technique was a novel bariatric operation based on the principles of Scopinaro’s biliopancreatic diversion, but eliminating the Roux-en-Y reconstruction of Douglas Hess’ duodenal switch modification and performing a Billroth II-type one-loop duodeno-ileostomy instead, located 250cm (since modified to 300cm) proximal to the ileocecal valve.3 Their data demonstrated similar weight loss and metabolic improvement as the more traditional two anastomosis duodenal switch without any increased risk of complication related to the loop reconstruction.3

Over the past several years, the SADI procedure has been gaining popularity in the US and around the world, not only as a primary procedure, but also a revisional procedure after SG. Given this increase in popularity, SADI has begun to garner the attention of bariatric societies to 1) determine if this is a valid procedure and, 2) if this procedure is one that should be added to our bariatric armamentarium. In May 2018, the International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders (IFSO) released a position statement on SADI, stating that it was a safe and effective procedure that should be considered as a surgical option for the treatment of obesity.4 This past year the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) Clinical Issues Committee reviewed the relevant published data and determined there were 18 publications with available data on over 1,700 patients undergoing SADI in the peer-reviewed literature. After review and deliberation, the ASMBS Executive Council concluded that SADI appears to be an effective primary and revisional bariatric operation with reduced nutritional and surgical complications compared to the Roux-en-Y configuration of the traditional duodenal switch. Following input by the membership, in March 2020 the ASMBS published an updated position statement to officially endorse SADI as an appropriate metabolic bariatric surgical procedure as a variant and modification of the classic duodenal switch.5

Historically the traditional duodenal switch procedure was less than one percent of all the bariatric procedures performed nationwide. This was likely due to the increased technical surgical complexity of the procedure, as well as the potential for increased nutritional issues. Both of these concerns are addressed with the SADI procedure. Since SADI has one less anastomosis than the traditional Roux-en-Y duodenal switch, the potential for surgical complications is reduced, yet obviously not completely eliminated since there are still staple lines and suture lines involved. Given that SADI is now an endorsed procedureby the IFSO4 and ASMBS,5 there will likely be an increase in the number of these procedures, and thus a potential increase in the number of complications specific to this procedure. One of these potential complications is the development of a leak after a SADI procedure. Given that a duodenal anastomosis could be a new concept for many bariatric surgeons, the prevention and management of these potentially life-threatening complications is one in which all bariatric surgeons should be well versed.

The best method to deal with leaks in any surgical procedure is to work toward preventing them in the first place. This, of course, is dependent on the surgeon’s experience, but there are a few pearls that can help a surgeon proceed quickly through his learning curve. The SADI technique that we utilize involves starting the procedure laparoscopically or robotically in the pelvis to count out and then tack up the small bowel 300cm proximal to the ileocecal valve. It is imperative, even at the start of the procedure, that an evaluation of the entire abdomen be performed before any stapling occurs because this will help determine if the procedure can be done safely. For example, excessive adhesions from pelvic surgery or an open cholecystectomy could create areas for potential leak or obstruction and perhaps should be avoided early in a surgeon’s learning curve with this procedure. The duodenum is then mobilized by carrying the greater curve dissection from the stomach down past the pylorus and along the duodenum to the level of the gastroduodenal artery, where the first portion of the duodenum is then transected. Care should be taken here to avoid excessive skeletalization and devascularization of the duodenum, which could potentially create areas of ischemia and necrosis. The ileum is then sutured to the duodenal staple line, and after creation of the enterotomies, a single layer hand sewn duodeno-ileostomy is performed with absorbable sutures. Finally, the SG is completed over at least a 40 French bougie. Standard surgical principles should apply here namely to avoid tension and to avoid areas that could cause a means of partial obstruction, such as narrowing at the angularis and kinking of the afferent limb. Creating a partial obstruction could cause an increase in pressure upstream, thereby leading to a blowout of a staple line or suture line.

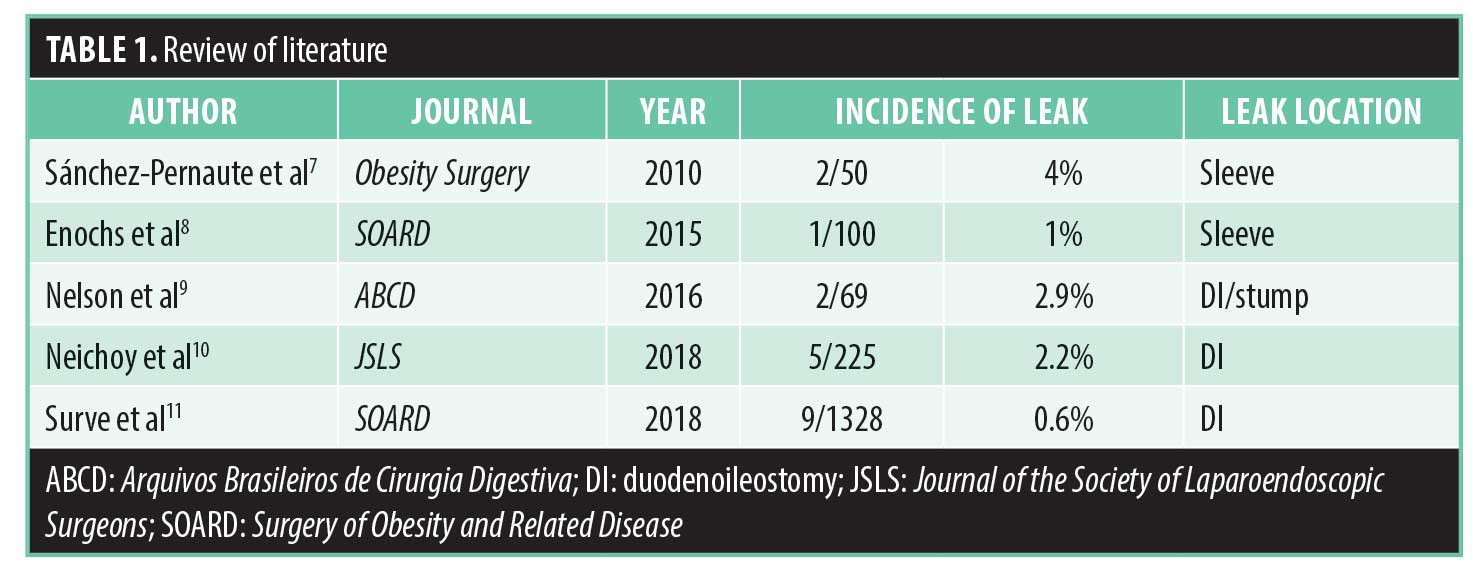

Recent studies have demonstrated that while the results are early and short term, there is an overall decrease in the incidence of surgical complications with the one anastomosis SADI procedure compared to the traditional two anastomosis duodenal switch, and in some cases, even less than the two anastomosis gastric bypass. In a review of the literature, Topart et al6 evaluated 19 studies that represented 1,041 single anastomoses patients who had their procedures performed across nine institutions. The procedures evaluated included 304 SADI-S procedures, 667 stomach, intestinal pylorus sparing (SIPS) procedures, and 70 single anastomosis duodeno-jejunal bypass with sleeve (SADJB-S). The overall early complication rate and reoperative rate among all these procedures was less than 1.6 percent. When evaluating specifically just the leak rate in the literature, it has ranged from 0.6 to 2.9 percent. The breakdown of the location of these leaks presented from the SG, the duodenal stump, and the duodenoileostomy (Table 1).7–11

Leaks from Sleeve Gastrectomy

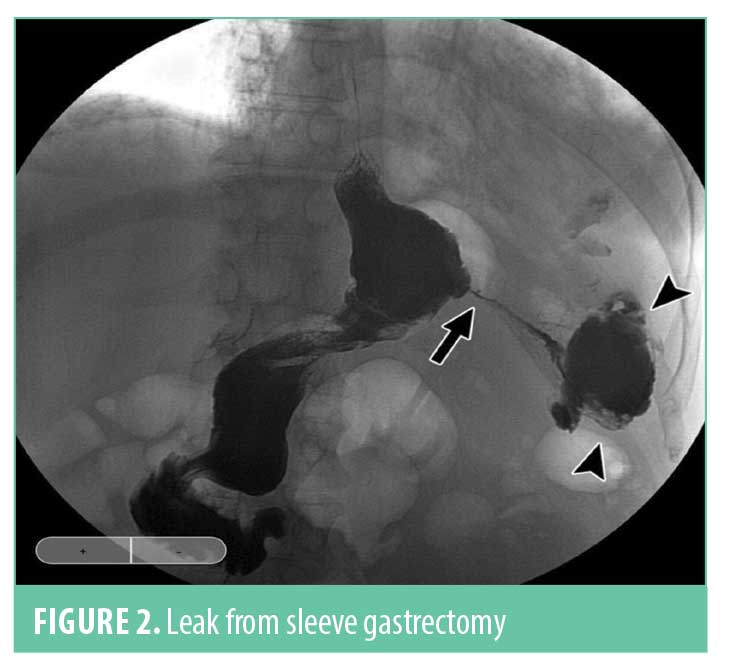

A leak from the SG portion of the procedure has historically been the most common area for a leak after a duodenal switch. The incidence has been reported as 1 to 4 percent, depending on the study evaluated. Over the last 5 to 10 years, the incidence has dropped as surgeon experience has increased in performing the SG as a stand-alone procedure. The most common area for a leak is in the upper one-third of the sleeve due to narrowing or stricture of the sleeve at the incisura angularis (Figure 2). This will cause an increase in pressure in the sleeve with a blowout at the upper portion of the staple line near the gastroesophageal junction since this is the weakest point in the sleeve. The treatment of a sleeve leak in the acute setting without a significant obstruction involves a washout of the affected area with resuturing or restapling of the sleeve. Many of these can heal completely if addressed early enough with minimal contamination. In the chronic setting or with a chronic fistula, it gets a bit more complicated. Nutritional support and antibiotics are required initially, combined with adequate drainage. Drains can usually be placed via a surgical approach or with the aid of interventional radiology, but recent studies have shown that drainage can also be facilitated with endoscopic techniques, such as an endoscopic wound vac or endoscopic septotomy. The most important aspect though for definitive treatment is to look for and relieve the obstructive point, which is usually at the angularis. This can be done with placement of an endoscopic stent, but in reticent cases, eventual surgical resection and Roux-en-Y reconstruction might be required.

Leaks from Duodenal Stump

Leaks from the duodenal stump can be a devastating complication. As with a sleeve leak, these duodenal stump blowouts result from increased pressure from distal obstruction with backup of duodenal contents. Many factors could contribute to this. They include, but are not limited to, postoperative adhesions, intraluminal hematoma, narrowing at the duodenoileostomy, inadequate stump closure, localized staple line hematoma or devascularization, thermal injury from electrocautery, and pancreatitis resulting in stump breakdown. It is important to note that, compared to the duodenal stump experience in the general surgery literature, the duodenum of a bariatric patient is relatively disease free without ulceration and scarring. As such, with proper surgical technique, the incidence of this complication can be minimized. When it does occur, the treatment is to stabilize the patient, drain the abscess, close the defect, and restore intestinal continuity. It is important to be aware, while this drainage is being performed, of possible involvement of the gastroduodenal artery, which will be in close proximity and might even be involved in the affected area. In the case of a stump leak, a duodenostomy tube will be required to achieve adequate drainage of the stump. Finally, and most importantly, it is imperative to find, identify, and relieve the distal obstruction that caused the buildup in pressure to begin with. Without doing this, the result will be a chronic fistula that will not heal.

Leaks from Duodenoileostomy

The last area to address for SADI leaks is leaks from the duodenoileostomy. In a recent multicenter review article by Surve et al,11 the incidence of leak at the duodenoileostomy was 0.6 percent (9/1328). This is lower than the reported incidence of anastomotic complications after RYGB or the traditional duodenal switch. It is important to keep in a mind a key difference between SADI and the gastrojejunostomy of the gastric bypass or the duodenoileostomy of the traditional duodenal switch. The loop construction in SADI can make this leak more problematic than the other two due to the presence of bile. As a result, to adequately manage this leak, it might be necessary to convert the patient to a two-anastomosis duodenal switch to divert bile away from the healing anastomosis. The other principles are similar to those mentioned before, which include oversewing and reinforcing the suture line with wide drainage and nutrition. The anastomosis might also be buttressed with omentum or falciform to facilitate healing. Finally, in the presence of a chronic fistula, it might be amenable to endoscopic management.

Conclusion

While less common than those from the two anastomosis procedures, leaks from SADI can occur. The sleeve staple line, duodenal stump, and duodenoileostomy are the three areas of concern for leaks in SADI. While less frequent, anastomotic leaks in the SADI patient can be more problematic due to the presence of bile. Finally, as a surgeon gains more experience with these technical considerations, the incidence of SADI leaks should be minimized. This will be a crucial step in the process of adding this promising new procedure to our bariatric armamentarium.

References

- English WJ, DeMaria EJ, Hutter MM, et al. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery 2018 estimate of metabolic and bariatric procedures performed in the United States. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2020;16(4):457–463.

- Prachand V, DaVee R, Alverdy J. Duodenal switch provides superior weight loss in super-obese (BMI>50) compared with gastric bypass. Ann Surg. 2006;244(4): 611-619.

- Sánchez-Pernaute A, Herrera MAR, Pérez-Aguirre ME, et al. Proximal duodenal-ileal end-to-side bypass with sleeve gastrectomy: proposed technique. Obes Surg. 2007;17(12):1614–1618.

- Brown WA, Ooi G, Higa K, et al. Single anastomosis duodenal-ileal bypass with sleeve gastrectomy/one anastomosis duodenal switch (SADI-S/OADS) IFSO position statement. Obes Surg. 2018;28(5):1207–1216.

- Kallies K, Rogers A. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery updated statement on single-anastomosis duodenal switch. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2020 Mar 30;S1550-7289(20)30149-0.

- Topart P, Becouarn G. The single anastomosis duodenal switch modifications: a review of the current literature on outcomes. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13(8):1306–1312.

- Sánchez-Pernaute A, Herrera MAR, Pérez-Aguirre ME, et al. Single anastomosis duodeno–ileal bypass with sleeve gastrectomy (SADI-S). One to three-year follow-up. Obes Surg. 2010;20(12):1720.

- Enochs PE. Review of single-port laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy as a routine procedure in 1000 patients. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12(7):1277.

- Nelson L, Moon RC, Teixeira AF, et al. Safety and effectiveness of single anastomosis duodenal switch procedure: preliminary result from a single institution. Arq Bras Cir Dig. 2016;29Suppl 1(Suppl 1):80–84.

- Neichoy BT, Schniederjan B, Cottam DR, et al. Stomach intestinal pylorus-sparing surgery for morbid obesity. JSLS. 2018;22(1):e2017.00063.

- Surve A, Cottam D, Sanchez-Pernaute A, et al. The incidence of complications associated with loop duodeno-ileostomy after single-anastomosis duodenal switch procedures among 1328 patients: a multicenter experience. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018;14(5):594–601.

Category: Past Articles, Review