Patient Perception of Surgical Preparation and Recovery Following Bariatric Surgery: A Phenomenological Study

by Karen Schulz, RN, MSN, CBN; Esther I. Bernhofer, PhD, RN-BC, CPE; Mary Ellen Satava, RN, BSN; Camille Ross, RN, BSN; Beth Janssen, RN, CBN; Beth Ianello, RN, BSN; and Diane Kompan, RN, BSN

by Karen Schulz, RN, MSN, CBN; Esther I. Bernhofer, PhD, RN-BC, CPE; Mary Ellen Satava, RN, BSN; Camille Ross, RN, BSN; Beth Janssen, RN, CBN; Beth Ianello, RN, BSN; and Diane Kompan, RN, BSN

Ms. Schulz is Nurse Manager, Bariatric and Metabolic Institute; Ms. Satava is Data Registry Coordinator, Enterprise Quality and Patient Safety; and Mss. Ross, Janssen, Ianello, and Kompan are Care Coordinators, Bariatric and Metabolic Institute, at the Cleveland Clinic in Cleveland, Ohio. Dr. Bernhofer is Associate Professor at Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio.

Funding: No funding was provided.

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Abstract: Background: Bariatric surgery as a treatment for obesity and associated chronic health conditions is increasing; although effective, it is not without risk. The success of bariatric surgery depends on how patients prepare for it and adhere to a recovery plan at home. Patients frequently face challenges that might not be fully understood by the nurses who educate and care for them. Methods: A qualitative, phenomenological design with focus group methodology was used to answer the research questions related to patient descriptions of personal experiences before and after surgery. Fifteen patients from a large Midwest United States quaternary care hospital participated. Results: Three overarching themes were discovered: 1) The meaning of health, 2) Patient experience along the perioperative journey, and 3) The “new normal” following surgery. Seven sub-themes were also uncovered, revealing that patients consistently experienced unexpected challenges in the areas of new eating habits, social support, and changes in family dynamics related to food. Participants often sought online resources to obtain information they felt was missing from that which was provided to them by their weight loss clinic and to validate their experiences. Patients valued interacting with other patients and often expressed frustration with the amount of time they had to wait for their surgery. Conclusions: Patients described a variety of frustrations, displayed ingenuity in obtaining information beyond the surgical education program provided to them by the nurses at the hospital, and looked forward to a healthier, yet challenging “new normal” life. When building a quality surgical education program, patient experiences and needs should be closely considered and valued.

Keywords: Patient education, focus groups, patient experience, chronic health education, bariatric surgery, qualitative research, nursing research

Bariatric Times. 2019;16(12):16–19.

Bariatric surgery is a life-changing procedure for many patients with obesity, but it is not without risk. Education regarding necessary lifestyle interventions, preoperation preparation, and education regarding postsurgery healthy behaviors are essential components of a comprehensive bariatric surgery program. This helps ensure that patients will recover well, experience limited complications, and attain better health and quality of life. The current patient bariatric education program in the large hospital system where this study took place was created through nursing assessment of potential patient needs. However, nurses (especially patient educators) found that patients still did not always adhere to postsurgical behavior and dietary recommendations. It is imperative for nurse educators in bariatric surgery programs to fully understand how patients perceive their presurgery education and their experiences following surgery so that any unaddressed needs can be met.

Background

Bariatric surgery is the most consistently successful method of weight loss in patients with morbid obesity.1 In 2017, there were 228,000 bariatric surgeries performed in the United States.2 However, bariatric surgery does carry risk. In a literature review by Khorgami et al,1 4.9 percent of patients who had undergone gastric bypass or gastric sleeve surgery were readmitted within 30 days of their surgery for postoperative complications. The top reasons for readmission were nausea, vomiting, or dehydration. A similar review by Rosenthal3 indicated that five percent of bariatric patients were readmitted within 30 days of their surgery, noting that specific readmission rates were based on different surgery types: 11.6 percent for the gastric bypass and 7.6 percent for the gastric sleeve.3 Although cause for readmissions to the hospital after bariatric surgery has been studied, the patient experience surrounding bariatric surgery has not been adequately explored. A better understanding of what patients know, do, and feel before, during, and after surgery might be helpful in educating and caring for them pre- and postoperatively, and lead to less risk for complications.

Study purpose and research questions.The purpose of this qualitative study was to understand how patients experience surgical preparation and recovery at home following bariatric surgery. In exploring patient experiences, the researchers aimed to understand more about perceptions of individual health, challenges, and resources available to those patients. The results may assist nurses on bariatric surgery teams to more fully understand patient experiences and thoughts about their health following bariatric surgery, which might lead to more effective care and better outcomes.

The primary research question posed for this qualitative study was as follows: In patients who underwent bariatric surgery in the past two years, how do they describe their experience at home within the first 30 days following surgery? The secondary research questions were: 1) What do bariatric patients identify as facilitators and barriers to healthy recovery at home? 2) How do they describe “being or feeling healthy?” 3) What do they wish they knew more about? 4) What do they describe as their challenges during this time? 5) What do they describe as positive experiences during this time? And 6) What education/information that they received prior to surgery do they describe as helpful to the postsurgery at home?

Methods

This study used a qualitative, phenomenological approach with a focus group methodology to answer the research questions.

Study setting. The study was conducted in the metabolic and bariatric surgery program of a large quaternary care medical center in the Midwestern United States. The surgery program there consists of a multidisciplinary team comprising surgeons, psychologists, dietitians, nurses, and administrative caregivers. The team works to support patients from initial inquiry through lifelong follow-up.

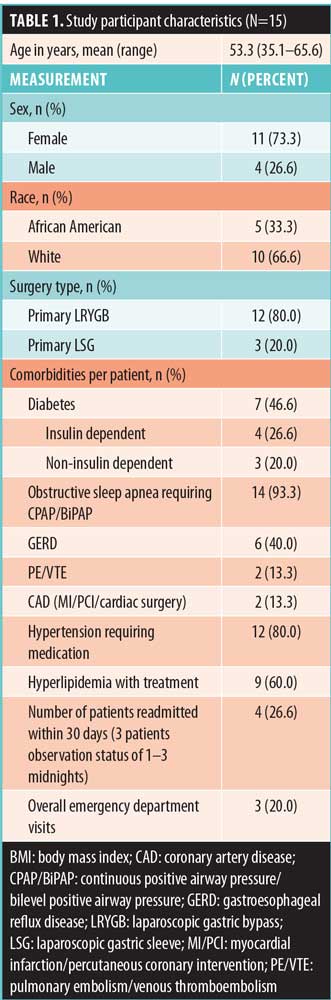

Sample. The sample for this study was recruited from patients identified in a surgical database who had undergone a primary laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB) or primary laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) surgery between the years 2015 and 2017. Inclusion criteria included those with an age greater than 18 years, having had weight loss surgery within the past 3 to 24 months, and English speaking. Patients were invited to participate in one of five focus groups. The cohort consisted of 15 total participants. All participants were functionally independent, with a hospital stay ranging between one and four days. Only one participant had a complication, which was minor (mild dehydration). Table 1 includes a description of the sample.

Data collection procedures. Following Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval, patients who met inclusion criteria were invited to participate in the study by a member of the research team by phone, using a set phone script. Prospective participants were informed that the purpose of the groups was to learn more about their experiences before, during, and after surgery. To elicit responses regarding recent memories, the participants were selected from a list of patients who had a primary bariatric procedure (gastric bypass or sleeve) within the past two years. No reimbursement or other incentive was provided to the participants for participation, and invitees signed informed consent prior to commencement of the focus group discussions.

Three interviewers, who were professionally trained in focus group facilitation techniques, led the discussions. The interviewers were purposely chosen for their nonclinical perspective and limited understanding of the postoperative bariatric care to limit biases.

A user-centered design (UCD) method was used to facilitate participant discussions in the focus group regarding personal experiences in the bariatric surgery perioperative period. UCD is a philosophy that places the person at the center, focusing on his or her experiences.4 Dwivedi et al4 describes the user-centered principle as human centered with data and information gathered directly from the users through interviews, surveys, workshops, focus groups, and/or field studies. In this study, the focus group method was used to obtain data using a nonbiased interviewer without direct connection to the caregivers in the bariatric program.

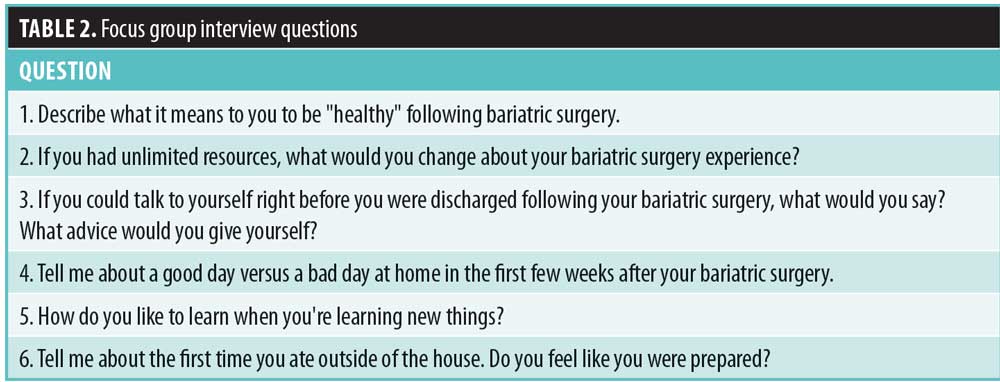

A total of five focus groups were convened. Interviewers directed the discussion through the use of a series of questions that revolved around the participant experiences at home within the first 30 days following surgery and were intended to solicit information without influencing patient responses to the questions. The interview questions are listed in Table 2. The sessions varied from 53 to 73 minutes in length and were held at the location where the surgery was done for the convenience of the participants. Group discussions were audio-recorded in an unobtrusive way using a digital audio recorder and transcribed for accurate compilation of results and data analysis. Consistency of the interviewing techniques and group leaders added to the reliability and validity measures throughout the process.

Instruments/technique. Six interview questions were asked during each focus group, with follow-up questions discussed as time permitted. At the beginning of the session, the first two questions were listed on a white board at the front of the meeting room for attendees who wished to write their responses to facilitate deeper conversation and discussion.

To generate further discussion, the interviewers used a research technique called a card sort. Card sorting is a participatory, user-centered technique used to facilitate discussion on attitudes, values, desires, and/or behaviors of participants as they relate to the subject being studied.5 The card sort technique included categorizing and ranking topics in a way that participants felt made the best sense to them and assisted in organizing findings into groups.

Data analysis. Van Manen’s approach to data analysis of phenomenological research was used to identify themes in the qualitative data.6 The nurse-comprised research team conducted the analysis with the assistance of a nurse scientist proficient in qualitative analysis. The group used a triangulation approach to qualitative data analysis; they listened to the five audio recordings individually and reviewed the typed transcripts as a group over a period of several months. A series of regular meetings were held to discuss the emerging themes, which included interpreting the meaning of patient responses, and the findings were compared to the relevant literature. Categorizing, coding, and grouping participant responses into themes and subthemes was done methodically, with any disagreements resolved through cooperative discussion. Qualitative data analysis software was not used due to unavailability.

Validity. Throughout this study, validity of the data and ensuing results were established by crafting a single purpose at the outset, with clear a priori research questions and rigorous data collection that utilized nonresearch-team interviewers to reduce bias during the focus group process.7 The research team also adhered to a predetermined, structured analysis procedure.8 Through triangulation, the work of individuals on the team was discussed and audited by the group before final consensus was reached.9,10

Results

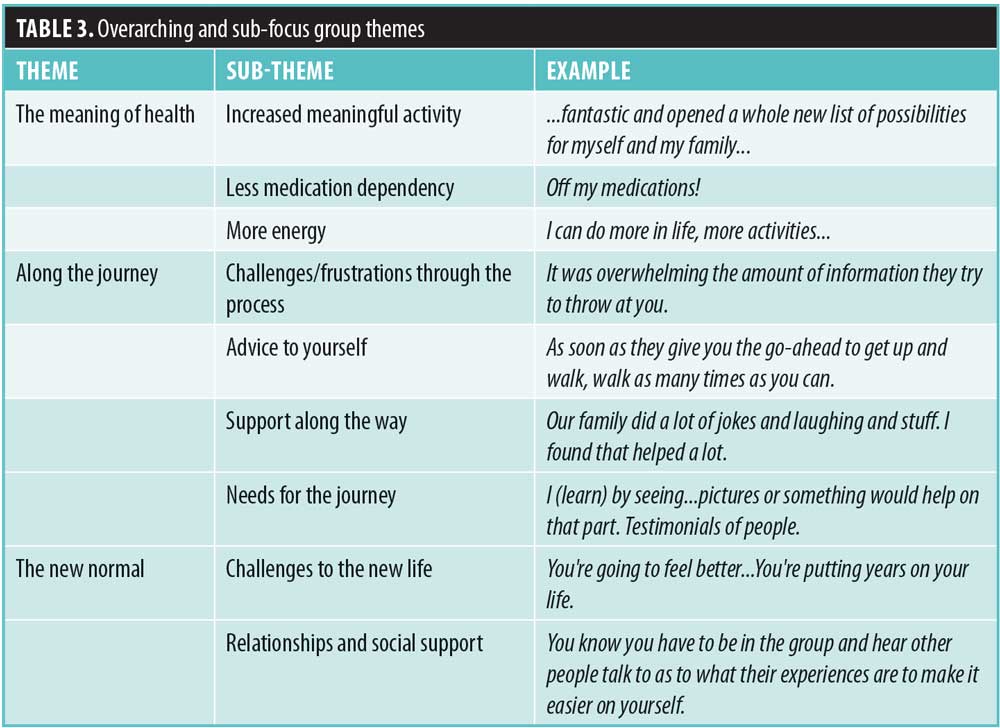

The data revealed three overarching themes: 1) “the meaning of health, 2) “along the journey,” and 3) “the new normal.” Seven subthemes were also identified. Table 3 provides an overview of the themes with subthemes.

“The meaning of health.” Participants in all focus groups expressed an overall renewed sense of health and universally expressed their satisfaction in having more energy; they described their perceptions of health in terms of increased meaningful activities. Participants talked about positive changes, stating, “I can do more in life, more activities,” “not as tired,” and “able to breathe better.” Participants also spoke frequently of a reduction in health problems and being “off … medications.”

Many statements of health independence also emerged throughout the conversations. In describing what it means for them to be “healthy,” some patients spoke of new experiences: “It means I can do more in life. Where I would get tired fast just climbing a flight of stairs … I am able to move, do more activities, and it gives me a different outlook on life and a reason to keep pushing forward.” Many patients included family/loved ones in their description of improved health: “It was fantastic, and it opened a whole new list of possibilities for myself and my family.”

“Along the journey.” Participant experiences varied between the positive and the negative. Frustrations were expressed by patients regarding logistics, such as parking, convenience of locations, and wait times. Several participants commented that “I would’ve liked to (have) gotten it done sooner” and “It takes time to go through the program.” Some expressed frustration with “all the prerequisites and so many meetings.” One person said “Half of it was the insurance part. If I could pay cash, I wouldn’t have to worry about it.”

Some of the most revealing answers came from the question, “What advice would you give to yourself before surgery?” Participants made statements about how important it was to follow the program, saying they would have told themselves, “Don’t be so hard-headed and listen, and read, and understand what you’re reading.” Others stated, “You’re going to feel better … you’re putting years on your life.”

There were general discussions about what participants did not expect. One person said, “Make sure you stay on the right track. Do what you are supposed to do.” Another said, “You need to remember your stomach is the size of a walnut with swelling.”

The most frequently encountered comment regarding challenges after surgery was about the “foamies” (a large foaming of saliva). Many participants in the focus groups seemed to be taken by surprise when foamies were experienced after surgery, stating, “You get all this saliva. Like it just comes up on the top of this stuck food.” Participants made comments about the difficulty adjusting to postsurgery eating with statements such as, “It just feels like it sits there. It doesn’t go anywhere” and “I had to retrain myself to eat.”

In response to the question “How do you like to learn when you’re learning new things?” there were comments about the comprehensive program book (distributed to patients as part of the surgery education) and its helpfulness: “This book is phenomenal” and “You refer back to it so often after you have surgery.” Some mentioned the “overwhelming amount of information they try to throw at you,” and “I read everything, read it page by page.”

The study team also noted there was a significant amount of conversation about patient use of social media for seeking information around the time of surgery. YouTube was the most frequently mentioned online source, followed by Facebook. One individual offered, “Pictures speak volumes to me.” Also, “instructions with photos” were mentioned as lacking from the surgery education program.

Several participants mentioned they wished the hospital would “hire somebody who’s had this done so that they could talk to us, relate to us,” and another said, “I think that patients who have had surgery should come to the shared medical appointments of those prior to surgery.”

Social support or lack of it was also mentioned as a major piece of the perisurgical journey. Focus group members expressed the challenges of eating with their families after surgery: “I felt really bad if I didn’t sit with my family while they were eating;” “It was awkward to me, and I knew I couldn’t eat it;” and “When we get together with friends, sometimes that is really hard.” Another participant said, “my family had a really negative attitude about it” and “It’s cheating or whatever to lose weight.” Others talked about the helpfulness of family and support, with comments such as, “Our family did a lot of jokes and laughing, and I found that helped a lot,” and “We meal prep and cook together.” Another participant commented, “It’s very helpful to have a support system. Without my kids, I could never have done it.”

“The new normal.” The third overarching theme, “the new normal,” included how the lives of the focus group members had changed after surgery in a way that transitioned them into a new way of eating and living. There were a wide range of experiences, and participants enjoyed talking about foods and their new eating behaviors throughout the sessions. “You have to learn how to stay within the parameters,” was a common remark. Everything from “eating is not as fun anymore” to expressing that foods they never liked before were now pleasurable: “Vegetables, broccoli, and stuff I didn’t like, I’m enjoying, so that is a plus.” Eventually participants talked about the new way of eating as part of their new life. One group member stated, “It’s only a tool [eating] that we learn how to use.”

Throughout “the new normal” conversation, positive and optimistic comments prevailed: “I have 14 grandbabies,” one participant said. “I want to at least live to see all of them get grown.”

Discussion

The focus group data provided useful descriptions of experiences of patient-participants and what they found most meaningful regarding support and encouragement along the way. For example, several of the participants commented on the volume of information presented to them in the preoperative time period. Their advice to themselves was “to read the book” and listen to what the program educators had to say. According to adult learning theory literature, people must hear things at least seven times before it becomes part of their general knowledge base.11 Margolis goes on to say that about 50 percent of information provided by healthcare providers is retained, of which, depending on conditions, 40 to 80 percent can be forgotten immediately, further highlighting the importance of repetition in meaningful learning. Ideas from Margolis11 to maximize retention include presenting the most important information first and being careful not to present too much information.

At least one participant mentioned the overwhelming amount of information offered in the program. In reviewing the adult learning literature, it might be best to consider presenting only the information that is important for the patient to remember. Although a recent study found that some patients actually suggested adding more information: “front-loading preoperative education so an informed decision about weight loss surgery could be made.”12

Challenges around the time of surgery included getting to multiple appointments, learning how to eat, dealing with “the foamies,” feeling unsure if they were “on track,” eating difficulties, and experiencing weight loss plateaus. Researchers in one study also reported other challenges that included difficultly identifying a full pouch, coping with emotional eating, food preparation, and adjusting to their new body image.12

Participants also described frustration with conflicting health education from multiple sources; this was echoed as a source of frustration for patients in other studies as well.13 With the expansion of online medical information, the amount of differing opinions that is easily accessible by patients on healthcare is a growing challenge.

Many participants talked about the value of social media as a source of support. Focus group participants verbalized that they were often online, reviewing bariatric videos and patient Facebook testimonials. Internet as a source of patient education is consistent with recent literature.12 A review of the literature by Smailhodzic et al14 found that improved emotional and information support were found by patients using social media, and patients who used internet support felt empowered and an enhanced psychological well-being.14 Although there is limited research in the area of online support groups, researchers in one study reported that 6 to 12 months after participating in an online support group, people with chronic illnesses had a significant reduction in symptoms of depression.15 More research is needed on the potential benefits of online support.

Participants talked about how helpful it would be to have a coach or mentor who has been through the surgery as part of the preoperative education process. Peer mentoring as an intervention in chronic disease care is intended to help people manage their chronic conditions by connecting them with individuals from similar life circumstances and/or similar health conditions.16 Riegel and Carlson17 showed higher self-care behaviors in patients with heart failure who were in a peer mentoring intervention group compared to those who did not receive peer mentoring. Embuldeniya et al18 conducted a comprehensive review of chronic illness peer mentoring literature, reporting that many positive outcomes of peer mentoring were found, such as reducing isolation, providing support, and contributing to normalization. However, an equal number of negative effects, such as social comparison, a competitive culture of success, and emotional misunderstandings, were also reported.18 Those who are planning educational programs to assist patients undergoing bariatric surgery might take a lesson from those who have studied interventions in patients with chronic illness who were cautiously recommending peer mentoring.

Another subtheme that was considered interesting by the research team of our study was patients wishing their weight loss surgery could have been done sooner or more quickly, but access was often limited or underprescribed. The American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) defines morbid obesity as a disease with a body mass index (BMI) of at least 40kg/m2 or a BMI of at least 35kg/m2 in the presence of high-risk comorbid conditions.2 Worldwide, over 2.5 million deaths annually can be attributed to obesity; in the United States (US), that number is over 400,000, second only to cigarette smoking.2 The ASMBS estimates that 20 percent of the US population with obesity suffers from severe obesity, impacting a population of over eight million people. With approximately 228,000 surgeries performed in 2017, only about 2.5 percent of patients who met the criteria for bariatric surgery who had access to it.

Limitations. This study was conducted in one large medical center and was limited by the experience of participants in a single midwestern state. Similar to most qualitative, focus-group studies, data were elicited from a small subset of volunteers who were engaged and willing to travel to a focus group. The perceptions of these highly engaged participants included in our study might not be generalizable accross multiple populations of weight loss surgery patients. However, qualitative research is not intended to be generalizable and considers the data and analyses derived from a small subset important information, contributing to the science of a distinct patient population that might not have yet been fully considered.

Recommendations

Based on our limited, qualitative study, the research team developed general recommendations for nurses who care for patients pre- and postoperative weight loss surgery:

- Reduce the amount of information that is presented to patients at any given time. Though our patients appreciated comprehensive resources with visual components, information is better absorbed if it is spread out over small but meaningful sessions.

- Include preoperative information about the “foamies” and other physical experiences in the sessions, as well as content about the effects of new eating behaviors on family and social interactions.

- Discuss the impact and content of social media with patients before and after surgery.

- Consider instituting peer mentoring for new patients as they prepare for surgery

- Conduct your own research, both quantitative and qualitative, to determine how your program’s current educational and interventional programs might be improved by considering what is most important to your patients of program addressing patient needs can reduce postsurgical complications and experience better patient outcomes.

Conclusion

Participants in this study provided valuable data regarding their experiences surrounding bariatric surgery and gave the study team important insight into what patients undergoing this type of life-changing surgery need. The responses to the interview questions revolved around three overarching themes that described their journey toward better health. Valuable insight regarding the heretofore undescribed experiences of patients who undergo bariatric surgery was discovered. Further research is necessary to determine how education programs based on the themes discovered in this study could impact complications, outcomes, and readmissions. Until then, the nurse investigators intend to use the patient-generated ideas to enhance the quality of their own surgical educational program regarding educational content, internet resources, peer mentoring, and social media.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patients who participated in this qualitative study and took the time to discuss their personal experiences in great detail, all for the hope that their stories would help others who will undertake the journey of bariatric surgery in search of better health and quality of life. The research team would also like to thank Brian Allyn, Paige Wesolowski, and Edwin Wortham, who served as our professional focus group facilitators.

References

- Khorgami Z, Andalib A, Aminian A, et al. Predictors of readmission after laparoscopic gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy: a comparative analysis of ACS-NSQIP database. Surg Endosc. 2016;30(6):2342–2350.

- American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. (2018). Estimate of Bariatric Surgery Numbers 2011-2017. https://asmbs.org/resources/estimate-of-bariatric-surgery-numbers. Accessed July 1, 2018.

- Rosenthal RJ. Readmissions after bariatric surgery: does operative technique and procedure choice matter? Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10(3):385–386.

- Dwivedi MSKD, Upadhyay MS, Tripathi A. A working framework for the user-centered design approach and a survey of the available methods. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications. 2012;2(4):12–19.

- Cataldo EF, Johnson RM, Kellstedt LA, Milbrath LW. Card sorting as a technique for survey interviewing. Public Opin Q. 1970;34(2):202–215.

- Van Manen M. (2016). Phenomenology of practice: Meaning-giving methods in phenomenological research and writing. London: Routledge.

- Creswell JW. (2012). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288.

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG. (1985). Establishing trustworthiness. Naturalistic Inquiry, Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

- Elo S, Kääriäinen M, Kanste O, et al. Qualitative content analysis: a focus on trustworthiness. Sage Open. 2014;4(1).

- Margolis RH. (2004). In one ear and out the other: what patients remember. Audiology Online. https://www.audiologyonline.com/articles/in-one-ear-and-out-1102. Accessed July 1, 2018.

- Groller KD, Teel C, Stegenga KH, El Chaar, M. Patient perspectives about bariatric surgery unveil experiences, education, satisfaction, and recommendations for improvement. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018;14(6):785–796.

- Carpenter DM, Geryk LL, Chen AT, et al. Conflicting health information: a critical research need. Health Expect. 2016;19(6):1173–1182.

- Smailhodzic E, Hooijsma W, Boonstra A, Langley DJ. Social media use in healthcare: a systematic review of effects on patients and on their relationship with healthcare professionals. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(1):442.

- Griffiths KM, Mackinnon AJ, Crisp DA, et al. The effectiveness of an online support group for members of the community with depression: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e53244.

- Knox L, Huff J, Graham D, et al. (2015). What peer mentoring adds to already good patient care: implementing the carpeta roja peer mentoring program in a well-resourced health care system. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(Suppl 1):S59–S65.

- Riegel B, Carlson B. Is individual peer support a promising intervention for persons with heart failure? J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2004;19(3):174–183.

- Embuldeniya G, Veinot P, Bell E, et al. The experience and impact of chronic disease peer support interventions: A qualitative synthesis. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;92(1):3–12.

Category: Original Research, Past Articles