Process Improvement: A Case Study Utilizing Pain Management Guidelines in the Care of Patients Following Bariatric Surgery

by Patti Murray, DNP, ANP-BC, ACHPN, RN-BC, and Donna Barker, MS, ANP-BC, RN-BC

by Patti Murray, DNP, ANP-BC, ACHPN, RN-BC, and Donna Barker, MS, ANP-BC, RN-BC

Ms. Murray is a nurse practitioner at Charlotte Medical Center in Charlotte, North Carolina. Ms. Barker is a pain nurse practitioner from Lake Barrington, Illinois.

Funding: No funding was provided.

Disclosures: The authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Abstract: Bariatric surgery is a disease-modifying procedure that assists with weight loss and mitigates or eliminates secondary comorbidities in patients with obesity. Patients with obesity who undergo bariatric surgery have a high rate of comorbidities, which places them at high risk for complications when attempting to control postoperative pain. Combining the Words, Intensity, Location and Duration measures, that Aggravating/Alleviating Factors, the (WILDA) pain assessment scale, and the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) protocols provided a framework that assisted us in the development of a new pain management protocol for patients who undergo bariatric surgery.

Keywords: Bariatric surgery, pain management, Words, Intensity, Location, Duration, Aggravating/Alleviating Factors (WILDA), enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS)

Bariatric Times. 2019;16(4):18–21.

According to the American Society of Bariatric and Metabolic Surgery (ASMBS), the first operation for the purpose of weight loss therapy occurred in 1950 at the University of Minnesota.1 Ten years later, Dr. Edward Mason developed the gastric bypass procedure. Since that time, multiple modifications of the original procedure, as well as improvements in surgical technique, have been developed. Coupled with technological innovations, bariatric surgery has developed into a highly specialized surgical field with excellent patient outcomes. Bariatric surgery can result in the improvement of multiple medical conditions, such as Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), cardiovascular disease, liver disease, urinary incontinence, myofascial disease, and arthritis.2 Multiple studies have identified a link between obesity and cancer, which suggests that bariatric surgery might also be effective in reducing rates of certain cancers.2 Bariatric surgery is well supported by research as a durable method of weight loss, and the more recent minimally invasive surgical approaches have reduced patient recovery time.3

Incidence

The National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease (NIDDK) classifies obesity as a chronic disease. Despite education and focus on wellness, obesity remains a major public health challenge in the United States. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC),3 35 percent of adults in the United States have chronic obesity. More than one-third of adults in the United States have morbid obesity, and, of those adults, more than 1 in 20 are considered to have extreme obesity. The incidence of obesity exceeds 20 percent in all 50 states, with the highest incidence occurring in the southern (32.4%) and midwestern (32.3%) regions of the United States.3 Between the years 2015 and 2016, the incidence of obesity in the United States was highest among individuals 40 to 59 years of age (40.2%), followed by ages 60 years or older (37%) and ages 20 to 39 years (32.3%).4 The annual medical cost spent in the United States related to obesity in 2008 was $147 billion. The care of a patient with obesity costs more than $1,400 annually compared to a patient of normal weight.2

Epidemiologic studies have identified a high body mass index (BMI) as a risk factor for a multitude of diseases that are modifiable by weight loss surgery. Patients with obesity are also at risk for many musculoskeletal diseases, including arthralgia and myalgia, with associated low quality of life (QOL) due to immobility, debility, and poor functionality. The combination of cardiac disease and T2DM with concomitant musculoskeletal disorders creates a cyclic scenario for sustained obesity. The secondary consequences, debility and immobility, can impact the patient socially, emotionally, and financially. Studies have reported there is a direct relationship between exercise, weight loss, and the treatment of musculoskeletal disease and surgical intervention, suggesting that weight loss surgery can positively impact whole-person, quality-of-life indicators.5

In addition to musculoskeletal disease and weight-bearing arthralgia, obesity can induce a systemic inflammatory state in which excess adipose tissue produces metabolically active pro-inflammatory cytokines and adipokines.6,7

This production can result in chronic pain syndromes, such as degenerative joint disease, osteoarthritis, fibromyalgia, low back pain, abdominal pain, and neuropathic pain. These pain syndromes have been associated with fatigue, stiffness, numbness, insomnia, poor sleep quality, anxiety, and depression. In a study by Okifuji and Hare,8 the likelihood of patients with obesity having a pain complaint was four times higher than the general population. The painful conditions associated with obesity can make the simple activities of daily living challenging, if not impossible. Investigators have estimated that 5 to 15 million Americans are negatively affected by obesity. Okifuji and Hare also found patients with chronic pain syndromes who also had obesity were more likely to take pain medications.8

In 2005, the American Pain Society (APS) guidelines for postoperative pain management6 recommended that pre-operative evaluation of patients with with complex medical issues is imperative for the most favorable postoperative outcomes. The APS recommends that patients should be assessed prior to surgery to establish a perioperative pain plan tailored to each patient’s individual needs and comorbities. In 2015, the APS recommended, that patients undergoing surgery should be managed using a multimodal approach to pain.9 Taking these guidelines into consideration, we began developing our own pain management protocol, which now recommends that all surgery patients meet with the pain nurse practitioner preoperatively to formulate an individualized perioperative plan. Patients on chronic opioid therapy are strongly advised to have a pre-operative evaluation to ensure a seamless postoperative course. All patients on long-acting or extended-release opioids are seen perioperatively in person or receive a telephone consultation as a condition of surgical clearance by the surgical team.

The perioperative consultation included the initiation of pain education, and counseling. Patients were educated about pain assessment and tools that would be used during the course of their care. Goals of care, including pain and functionality in the context of the postoperative course, were discussed. A mutually agreed upon plan was put in place with orders for the postoperative care. Patients on long-acting opioids perioperatively were asked to bring their healthcare provider’s contact information to ensure continuity of care at the time of discharge.

We have developed a perioperative pain management guideline specifically for the care of the bariatric surgical population to ensure continuity of care. This patient population presents with innate challenges due to lifestyle habits and potential emotional dysfunction. We worked with a single group of four bariatric certified physicians who supported the process improvement project. The goals of the project were to prevent opioid withdrawal in patients on chronic opioid therapy, which could potentially confound care in the immediate postoperative course. The project also sought to prevent inappropriate use of the intensive care unit (ICU) in the immediate perioperative period, monitor the need for opioid reversal with naloxone in the perioperative patient, and improve patient satisfaction in this complex patient population.

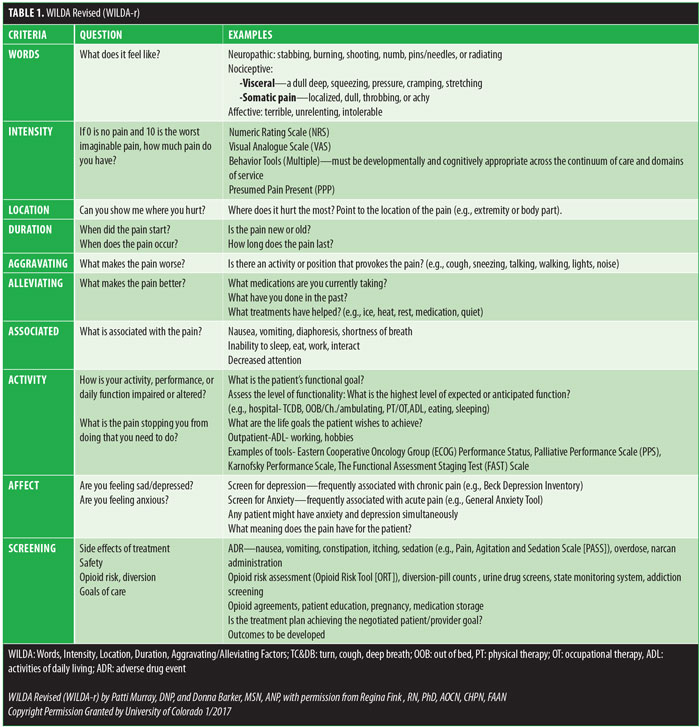

We found that patients who met with the pain nurse practitioner prior to surgery had more realistic expectations related to pain goals and management, which we believe helps decrease the risk of oversedation. Secondary outcome measurement included tracking with our interdisciplinary team. Outcomes related to the interaction with physical therapy (PT) and occupational therapy (OT) improved with fewer missed appointments due to uncontrolled pain or side effects of treatment. Nutritionists found that patients were able to have their swallow evaluation earlier, and time to feed was shorter. Using Fink’s WILDA approach,5 the acronym for Words, Intensity, Location, Duration, Aggravating/Alleviating Factors, we were able to create WILDA-Revised (WILDA-r), multimodal treatment algorithm that acts as a guide but is not rigidly prescriptive (Table 1). It allows for individual surgical preference and approach for the different types of bariatric surgical techniques. This guideline is one that we feel is flexible and applicable to most surgical techniques and surgeries.

Pain Plan Case Study

Mrs. B was a 41-year-old woman who was 5 foot 4 inches tall, weighed 351 pounds at clinical presentation, and had a BMI of 60.24kg/m2. She had chronic low back, knee, hip, and ankle pain from joint overload, which had been present for more than five years. She reported trying “every kind of diet imaginable” to lose weight. The most weight lost was 26 pounds, which she attributed to a starvation diet. She reported using ice, heat, topical analgesics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and prescribed opioid combination drugs for pain relief. She rated her daily pain as 6 out of 10 on average, noting that the pain medication was generally not effective.

Mrs. B was referred to the bariatric team by her internal medicine physician, who was concerned by her increasing metabolic syndrome comorbidities, T2DM, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and obesity. Mrs. B’s medications included metoprolol XL (100mg once daily), oral pantoprazole (20mg daily) for acid reflux, oral metformin (100mg daily), and oral insulin glargine (34 units daily) for T2DM. For pain management, she used hydrocodone/acetaminophen (10/325mg, 6 tabs in 24 hours) for her chronic joint pain. In anticipation of surgery, the NSAIDs were discontinued and oxycodone ER (10mg every 12 hours) was initiated. Her daily morphine equivalents, using the CDC conversion, totaled 90mg, thus identifying her as opioid tolerant and dependent, requiring a pain management consult.

Mrs. B and her husband met with the clinic’s bariatric surgeon, nurse, dietitian/nutritionist, psychologist, and physical therapist prior to surgery. She brought her insurance referral, a copy of her latest physical, and lab work. The different types of bariatric surgery were explained in detail, including laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (LAGB), sleeve gastrectomy (SG), and Roux-ex-Y-gastric bypass (RYGB). Mrs. B opted for the SG. She was required to attend a class prior to surgery that reviewed her preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative courses of treatment. In addition, she received referrals to meet with the pulmonologist and pain team for perioperative assessment.

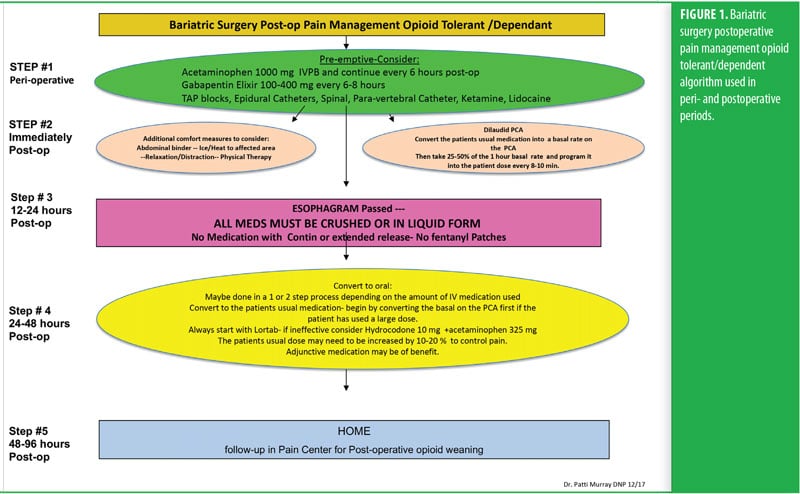

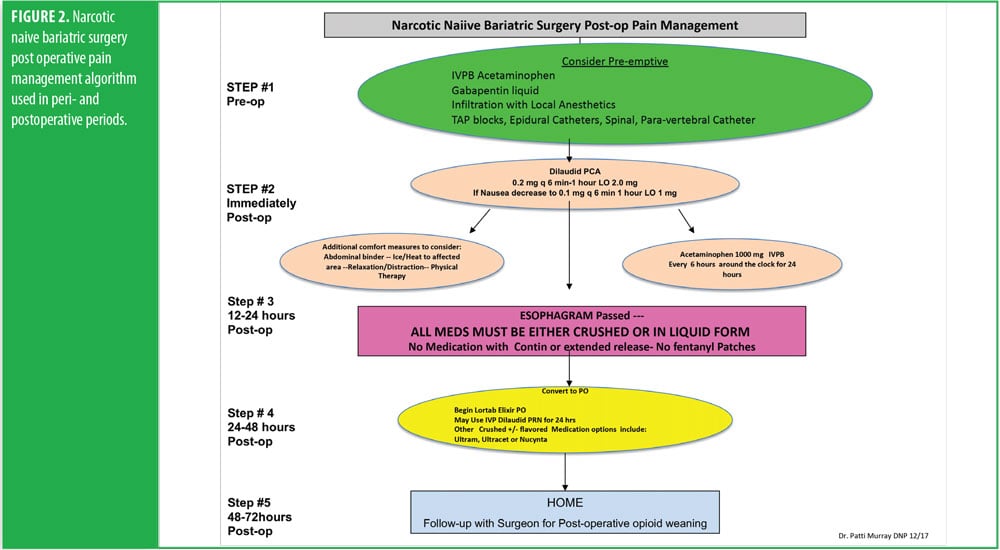

One week before her surgery, Mrs. B met with the pain team, who performed a comprehensive baseline pain assessment using the WILDA-r approach. She was able to describe her pain in words (i.e., stabbing and achy), intensity (i.e., 4–5/10 on a 0–10 pain scale), location (back, hip, and knees), duration (i.e., constantly for the past 3 years), and aggravating/alleviating factors (i.e., pain increased with activity and improved when lying down). Her pain severely impacted her QoL: she had declining ability to do her activities of daily living and felt “defeated and depressed” due to her lack of ability to lose weight on her own. She denied using her medication other than as prescribed and reported that she never ran out of medication before the end of the prescription period. She was followed closely in a pain center with the goals of increasing her activities-of-daily-living functioning and weaning off of the pain medication. A perioperative plan was created using her WILDA-r assessment and opioid tolerant and dependent treatment plan (Figures 1 and 2). The team educated her on preparedness planning related to the perioperative plan, expectations, and postoperative goals. Her pain management consult and perioperative pain management plan was sent to the preoperative surgery department to be initiated on arrival the day of surgery.

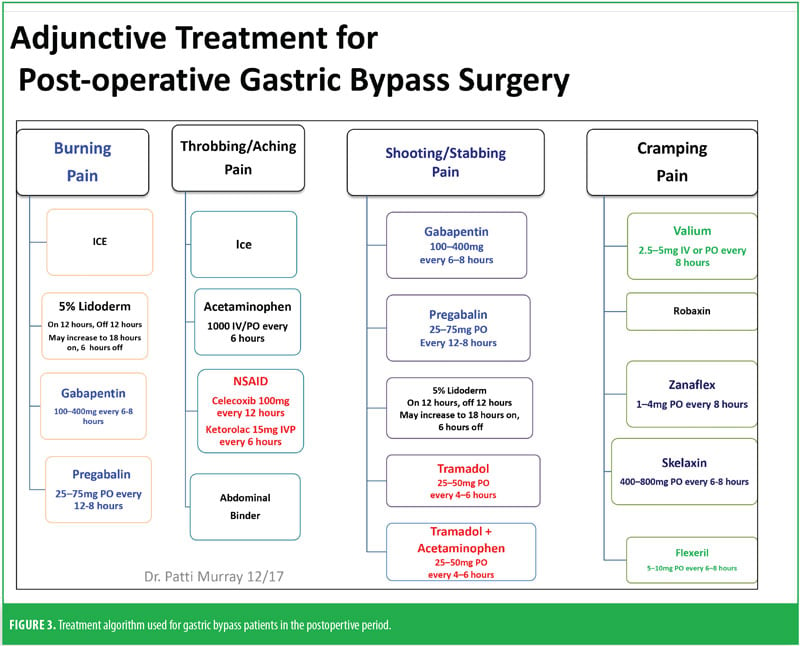

The RYGB algorithm was used for Mrs. B. because she was opioid tolerant (Figure 3). The bariatric surgical team, including the surgeon, nurse practitioner (NP), physician assistant (PA), and nurses, were previously educated on the use of WILDA-r. This facilitated communication between the members of the bariatric team through the use of a common language to regarding the patient’s assessments, treatments, education, and quality improvement related to outcomes.

Preoperatively, Mrs. B was given 1g acetaminophen intravenous (IV) and 400mg oral liquid gabapentin. She was managed intraoperatively by anesthesia. Postoperatively, she was on an opioid-tolerant, patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) of 0.3mg hydromorphone every 10 minutes, with a lockout of 2mg/hour until she passed a barium swallow. Adjunctively, strips of 5% lidocaine patches were placed along her incision lines 12 hours on and 12 hours off. She was offered ice and heat packs for comfort, which she declined. She did not have any muscle spasms and she reported her postoperative pain to be well controlled. She demonstrated appropriate functional outcomes and did not require an escalation in her pain treatment plan. She was able to use her incentive spirometer, her oxygen saturation was maintained above 93 percent, and she was ambulatory with assistance from the PT on the day of surgery.

Immediately after Mrs. B passed the barium swallow test, bariatric clear liquids were initiated, her PCA was stopped, and the patient transitioned to oral liquid medications (gabapentin liquid oral 300mg every 8 hours and hydrocodone/acetaminophen liquid 7.5/500mg per 15mL every 4 hours as needed for breakthrough pain) and a liquid diet. Additionally, the lidocaine patches were continued. If the hydrocodone/ acetaminophen liquid failed to adequately control her pain (i.e., ≥8/10 on pain scale), she could be administered hydromorphone liquid 0.5mg every four hours PRN, of which she only used once immediately following removal of PCA.

Mrs. B was discharged from the hospital 48 hours postsurgery. She was prescribed an oral solution of hydrocodone and acetaminophen (5 to 10mL every 4 hours as needed for pain) to be taken for one week post discharge and gabapentin elixir (300mg every 8 hours around the clock for neuropathic pain) to be used for 30 days, and lidocaine patches 5% to be placed on the surgical incision lines. Her recovery was uneventful, and she had lost 21 pounds by her first postoperative visit one week after surgery. Postoperative self-weaning of hydrocodone/acetaminophen elixir was encouraged. Opioid use was discussed and it was decided that if opioid was still required to manage pain greater than a 5 out of 10, the patient would make a subsequent appointment with the pain management nurse practitioner .

Discussion

Our goal is to wean patients off opioids as quickly as possible after surgery, followed by discontinuation of the gabapentin. If the patient is having difficulty with weaning off the opioids, as assessed during the first postoperative visit, a return visit to the pain team is recommended to revise the pain plan in accordance with the patient’s needs. In this patient case study, the team support assisted the patient in achieving rapid weight loss, which positively impacted her pain and allowed a rapid weaning off of opioids. We did not have missed appointments, as the pain team was responsible for prescribing medications if patient self-weaning was a challenge. Long-term follow-up for more than 2 to 3 postoperative consults was rarely required.

Summary

Despite the tremendous progress that has been made in our understanding of the pathophysiology of pain, there are few randomized studies that provide reproducible, generalizable, evidence-based recommendations, protocols, or guidelines.10 There remains a great need for the development of guidelines grounded in the pathophysiologic understanding of acute pain, as well as the need for clinicians to implement evidence-based, procedure-specific, multimodal analgesic protocols focusing on outcomes. Perioperative collaboration between the various members of the healthcare team (e.g., anesthesiologists, surgeons, nurses, PT) is imperative for the integration of effective perioperative pain management protocol.

Our project with the bariatric algorithm is in line with Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) protocol, which employs evidence-based, fast-track recovery paradigms. We were able to reduce the hospital stay, decrease adverse drug reactions, potentially decrease postoperative morbidity, and shorten the postoperative recovery course while improving patient satisfaction. Future research should be directed at prospective, randomized clinical studies focused on the evaluation combined of different analgesic combinations as part of multimodal analgesic treatment regimens in combination with interventional management in the postoperative period.

References

- American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. The story of obesity surgery. 2004. Available: https://asmbs.org/resources/story-of-obesity-surgery. Accessed April 1, 2019.

- GBD 2015 Obesity Collaborators, Afshin A, Forouzanfar MH, et al. Health effects of overweight and obesity in 195 countries over 25 years. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(1):13–27. Epub 2017 Jun 12

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Overweight and Obesity Data and Statistics: Adult Obesity Prevalence Maps. https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/prevalence-maps.html. Accessed April 1, 2019.

- Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2015–2016. NCHS data brief, no 288. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2017.

- Fink R. Pain assessment: the cornerstone to optimal pain management. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2000;13(3): 236–239.

- Gordon D, Dahl J, Miaskowski C, et al. American pain society recommendations for improving the quality of acute and cancer pain management: American Pain Society Quality of Care Task Force. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(14):1574–1580.

- McCaffery M, Ferrell B, O’Neil-Page E, Lester M, Ferrell B. Nurses’ knowledge of opioid analgesic drugs and psychological dependence. Cancer Nurs.1990;13(1):21–27.

- Okifugi, A, Hare BD. The association between chronic pain and obesity. J Pain Res. 2015;8:399–408.

- Chou R, Gordon DB, de Leon-Casasola OA. Management of Postoperative Pain: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American Pain Society, the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ Committee on Regional Anesthesia, Executive Committee, and Administrative Council. J Pain. 2016;17(2):131–157.

- White PF, Kehlet, H. Improving postoperative pain management: what are the unresolved issues? Anesthesiology. 2010;112(1):220–225.

Category: Case Study, Past Articles