Raising the Standard: Team-based Care: Enhanced Recovery in Bariatric Surgery

by Anthony T. Petrick, MD, FACS, FASMBS, and Dominick Gadaleta, MD, FACS, FASMBS

by Anthony T. Petrick, MD, FACS, FASMBS, and Dominick Gadaleta, MD, FACS, FASMBS

Dr. Petrick is the Quality Director at Geisinger Surgical Institute and Director of Bariatric and Foregut Surgery for Geisinger Health System in Danville, Pennsylvania. Dr. Gadaleta is Chair of the Department of Surgery at Southside Hospital and Director of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery at North Shore University Hospital, Northwell Health in Manhasset, New York; and Associate Professor of Surgery at Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell in Hempstead, New York.

Funding: No funding was provided for this article.

Disclosures: The authors reports no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Bariatric Times. 2019;16(4):8–10.

“Coming together is a beginning. Keeping together is progress. Working together is success.”

-Henry Ford

In October 2018, we focused on comprehensive team-based care for the bariatric patient. This month, we will take a closer look at perioperative team-based care, also called enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS). The key steps in ERAS are as follows: 1) protocol development, 2) standardizing order sets, 3) implementation of protocol, and 4) outcomes measurement. Creating standardizations and pre-selection of ERAS elements helps drive adherence to protocols and assure best practices.

One of the first to advocate for the concept of standardized multimodal surgical care was Professor Henrik Kehlet from the University of Copenhagen in Denmark in the 1990s. Fearon and Ljungqvist1 created a collaborative group on perioperative care called the ERAS® Study Group, which had an evidence-based consensus protocol published for patients undergoing colonic surgery. The first ERAS® Symposia was held in Stockholm, Sweden, in 2005.2 McGlynn et al3 reported that most patients in the United States only receive about 55 percent of the care intended by medical practitioner. The ERAS® study group recognized this concept and reported data indicating that adding a protocol was not enough to change practice and that measuring “adherence” was the key to improving outcomes.4 In 2010, the ERAS® Society was officially registered as a non-for-profit medical society based in Stockholm, Sweden.

Enhanced recovery protocols are organized by phases of care (Figure 1). The objectives differ based on the acuity and risks associated with the procedure. Hallmarks of the pre-admission phase include nutrition and patient education. In bariatric patients, nutrition is focused on high-protein liquid diets. The use of carbohydrate loading is unclear in the bariatric population due to the prevalence of diabetes. Education should include skin preparation and set expectations for hospital stay, diet, activity, and postoperative pain control. The postanesthesia care unit (PACU) preoperative phase should include a multimodal pain management plan, skin preparation, and orders for venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis, antibiotics, and glucose monitoring.

The intraoperative phase of care emphasizes communication between the anesthesia and surgical teams. The World Health Organization (WHO) Safe Surgery Checklist5 provides an opportunity to communicate the enhanced recovery elements to the entire operative team. The checklist identifies a “time out” period in which the surgical team must verbally review the patient, surgical procedure, and side/site to confirm that they are performing the correct operation on the correct patient and site.

These teams should have a standardized plan to minimize the use of lines and urethral catheters, as well as opioid use. The routine use of transversus abdominus plane (TAP) block should be considered in all bariatric procedures as a tool to minimize use of opioid pain medications.

The postoperative inpatient phase of care is characterized by early nutrition and ambulation. If lines, drains, or catheters were utilized, they should be removed as soon as clinically possible. Multimodal pain regimens should prioritize scheduled dosing of nonopioid pain medications as this has been shown to reduce opioid requirements.

Confirmation of postoperative appointments and care team contact information (e.g., a “HELP” card) should be a routine part of the postoperative discharge process.6 Assessment of opioid needs and prescribing should be individualized according to patient needs, as should risk-assessment for extended VTE prophylaxis. A scheduled multimodal pain regimen should be continued for 3 to 5 days after surgery. Postdischarge phone calls from the surgical team are an important tool to reduce emergency room visits and improve patient satisfaction.

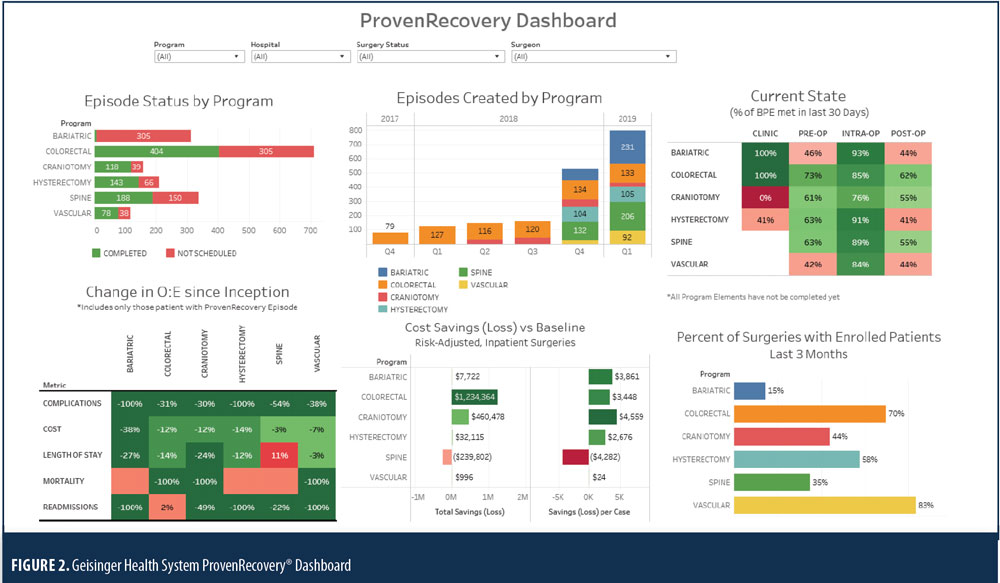

Tailoring standardized order sets according to specific enhanced recovery pathways is essential to their implementation as part of the ERAS process and will help to ensure patient adherence to prescribed treatment regimens. Electronic medical records enable electronic reporting, and enhance recovery order sets can be programmed to pre-select preferred enhanced recovery measures, which might help improve the healthcare team’s adherence to protocol elements. See Figure 1 for an example of a comprehensive enhanced recovery dashboard used by Geisinger Health in Danville, Pennsylvania.

Programs interested in the development and implementation of enhanced recovery pathways should develop clear outcomes objectives. Early studies of enhanced recovery protocols focused primarily on clinical outcomes demonstrating improvements in length of hospital stay (LOS), readmission, reintervention, mortality and complications.7 These outcomes measures have become the benchmarks for success as enhanced recovery pathways are developed in clinical programs, such as in bariatric and metabolic surgery. While these remain important metrics, there might not be much room for improvement in clinical outcomes by experienced bariatric centers that have already implemented many of the quality improvement measures through standards set forth by the Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Accreditation and Quality Program (MBSAQIP) for accreditation. It is important for clinicians to recognize additional benefits of implementing enhanced recovery protocols, such as cost reduction, opioid use reduction, and improvements in patient experience. For outpatient procedures or those requiring overnight stays, opioid use reduction might be the primary outcome benefit. For both simple and complex procedures, the standardization associated with enhanced recovery creates opportunities for significant cost savings. Finally, standardization benefits not only the surgical care team, but also the nursing and ancillary personnel who frequently struggle with adhering to care protocols when care pathways vary between providers. Coordination between all healthcare providers along the continuum of care is critical to improving the patient experience.

References

- Fearona K, Ljungqvist O, Von Meyenfeld M, et al. Enhanced recovery after surgery: A consensus review of clinical care for patients undergoing colonic resection. Clin Nutr. 2005;24(3):466–477. Epub 2005 Apr 21.

- ERAS® Society. History of the ERAS Society. http://erassociety.org/about/history. Accessed April 1, 2019.

- McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, et al. The quality of health care delivered in adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2635–2645.

- Maessen J, Dejong CH, Hausel J, et al. A protocol is not enough to implement an enhanced recovery programme for colorectal resection. Br J Surg. 2007;94(2):224–231.

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for Safe Surgery. Geneva, Switzerland; WHO Press: 2008.

- Morton JM. The first metabolic and bariatric surgery accreditation and quality improvement program quality initiative: Decreasing readmissions through opportunities provided. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10(3):377–378.

- Alvarez MP, Foley KE, Zebley DM, Fassler SA. Comprehensive enhanced recovery pathway significantly reduces postoperative length of stay and opioid usage in elective laparoscopic colectomy. Surg Endosc. 2015;29(9):2506–2511.

Category: Past Articles, Raising the Standard