Recognizing and Addressing Physician Burnout

by Adrian Dan, MD, FACS, FASMBS

by Adrian Dan, MD, FACS, FASMBS

Dr. Dan is Medical Director, Weight Management Institute at Summa Health in Akron, Ohio, and Associate Professor of Surgery at Northeastern Ohio Medical University (NEOMED) in Rootstown, Ohio

Funding: No funding was provided.

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Bariatric Times 2021;18(10):8–10

Not long ago, one of my American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) colleagues reached out to clarify a minor mix-up in her emails. This situation we all know too well, as we tend to responsibilities taken on beyond our clinical duties. The explanation that followed was a sobering reminder of a perilous occupational hazard for surgeons. One of her surgical partners died from suicide. Such a tragic event leads to much more than just absorbing patients to one’s clinic or operative schedule. It takes a massive emotional toll as families, colleagues, patients, institutions, and communities grieve their loss together.

Sadly, accounts of physicians committing suicide are much too frequent, and the risk is significantly higher than that of the general population.1 Everyone reading this column has probably known an individual in their professional life who has succumbed to such tragedy. A common theme seems to be the shock and surprise expressed by others, as the signs are difficult to detect. Individuals who seem to be in complete control can yield to unsurmountable pressures and enter an inescapable abyss. Regrettably, we have seen this first-hand at my own institution.

As medical professionals, we contend with much more than long hours and the heavy burden of clinical responsibility. Early in our careers, we might feel guilty for leaving the hospital at a decent hour. We still possess some youth and energy left over from training and strive to earn our keep. As our practices mature, hours get longer and responsibilities become greater. We further develop professionally and take on administrative and service duties to serve our institutions and professional societies. Our colleagues in private practice must also contend with the difficulties of running a business. We do our best to maintain personal relationships and allocate time devoted to family. Add to that a global epidemic, a growing backlog of cases, and an increasing demand for metabolic surgery, and it is easy to see how any one of us could be overwhelmed. Our approach to do it all might be well intended and ingrained in our DNA, but it is certainly unsustainable and not unique to our specialty.

Without a doubt, I am as guilty as anybody of overloading my clinical schedule, taking on excessive additional responsibilities, and finding it hard to actually say no once in a while. Imagine my surprise, a couple of years ago, when my surgical fellow at the time (now our junior partner), asked me to include a discussion on “work–life balance” in our didactic schedule. My own lack of knowledge about physician burnout and its potentially catastrophic consequences quickly became apparent. It led me to reconsider my personal work–life balance and the professional responsibilities that I assume.

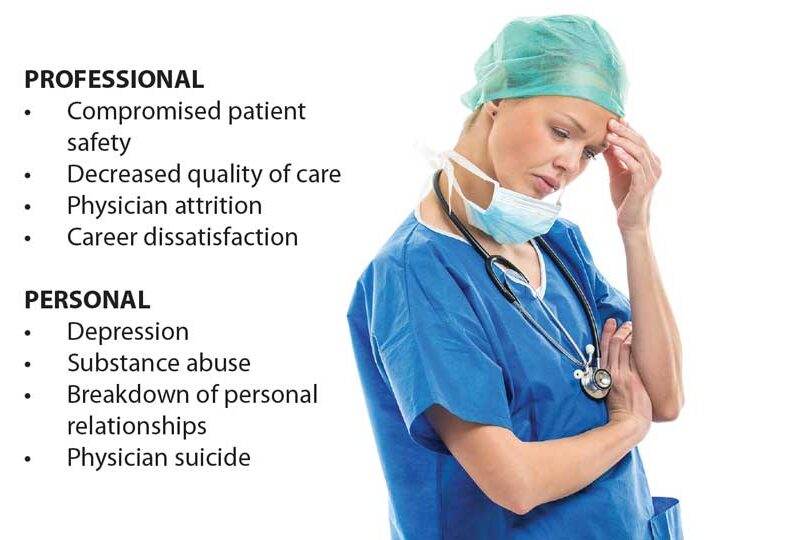

Wellness has numerous facets, which include the psychological, physical, emotional, social, and professional. Various factors that we contend with might threaten our well-being. Among them are professional regulations, loss of autonomy, inefficient workplace processes, difficult coworker relations, demanding administrative duties, medico-legal matters, and the infinite medical record charting responsibilities.2,3 It is not surprising that an estimated 50 percent of practicing surgeons and 70 percent of general surgery residents meet the established criteria for burnout.4,5 In addition, a poor balance and lack of attention to one’s own healthcare needs can result in frustration, emotional exhaustion, and doubt of personal accomplishment. There is a palpable correlation between this perfect storm of burnout emotions and its after-effects, such as compromised patient safety, decreased quality of care, physician attrition, career dissatisfaction, depression, substance abuse, breakdown of personal relationships, and even physician suicide.6

While pondering a topic for this installment of Perspectives, it became clear that this concern should take precedence in the very next issue. True to the column’s mission statement, we aim to bring attention to matters pertinent to professionals in bariatric surgery and obesity medicine. This time, the epidemic is physician burnout and the patients are us. At my own institution, this hazard is taken seriously, but, sorrowfully, after the loss of some of our own. I didn’t have to look far to find a champion for physician wellness and burnout prevention. Dr. Ronald Jones is an internal medicine physician whose research interests and endeavors have greatly increased our awareness of this subject. Fortunately, there are actions that can be taken to achieve a better work–life balance, recognize burnout, and prevent tragedy if we sense that one of our colleagues is struggling. In his portion of this issue, Dr. Jones discusses the topic of physician wellness, as well as the steps that can be taken to combat burnout for physicians across medical specialties.

References

- Schernhammer ES, Colditz GA. Suicide rates among physicians: a quantitative and gender assessment (meta-analysis). Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(12):2295–2302.

- Senturk JC, Melnitchouk N. Surgeon burnout: defining, identifying, and addressing the new reality. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2019;32(6):407–414.

- Dimou FM, Eckelbarger D, Riall TS. Surgeon burnout: a systematic review. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;222(6):1230–1239.

- Elmore LC, Jeffe DB, Jin L, et al. National survey of burnout among US general surgery residents. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;223(3):440–451.

- Brandt ML. Sustaining a career in surgery. Am J Surg. 2017;214(4):707–714.

- Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH. Executive leadership and physician well-being: nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(1):129–146.

Guest Perspective

by Ronald Jones, MD, FACP

Program Director, Transitional Year Residency; Chair, GMEC Wellness Subcommittee; Summa Health System

“Is there something wrong with me?”

Tricia, in her fifth year of surgical practice after residency, is having a typically busy week. Her morning cases held few surprises, but as she looks at her hospital list, her patients blend together and all seem to be the same person. She sighs as she picks up a patient satisfaction survey placed on her desk from the recent quarter. Her scores are running lower than some of her peers.

“I took a vacation last week that was so relaxing, but I feel just as tired after a few days back to work. I wonder if there is something wrong with me?”

Tricia’s colleagues would describe her as positive and cheerful, but they aren’t aware that she is, at times, having feelings of anxiety that she has not experienced since her college years. She has thought about seeing a counselor, but she is concerned that it might affect her career if it becomes known. Later, after the kids are in bed, she sits at home in her pajamas trying to finish up notes in the electronic medical record (EMR). The blue screen of her laptop bathes her bedroom in the modern light of isolation. “I guess I just need to try harder tomorrow,” she says to herself with a sigh, closing the keyboard and falling asleep.

Are you feeling a little like Tricia? Me too. There is a strong likelihood many of us are working while already experiencing burnout—a prolonged, work-related stress reaction that turns patients into irritants, saps our joy as doctors, and leaves us perplexed and emotionally exhausted. There is a lot being written about this reality right now, especially since pandemic conditions have highlighted healthcare worker exhaustion to the public. But what can you and I do about it as practicing physicians?

Our profession attracts focused workers who are trained by medical culture to be able to ignore or minimize personal needs for long periods and who rarely seek help from others. Shouldn’t we minimize or ignore the signs of burnout as just part of the job? New information about burnout and well-being says otherwise. We can learn to identify signs of burnout and address it with intentionality and rediscover some of our joy as doctors along the way.

“Burnout doesn’t look like what I thought.”

The prevalence of burnout is higher than you might think. Physician burnout is measured at 54 percent nationwide. Forty percent of surgeons showed signs of burnout in a recent survey, and 30 percent had signs of depression.1

The severity of the issue can be seen in the sporadic but ongoing occurrence of suicide among physicians. Has your health system endured such loss? Six percent of surgeons have experienced suicidal ideation in the preceding 12 months. Three hundred to 400 physicians die by suicide each year—the equivalent of three graduating medical school classes. This represents a 3 to 5 times higher incidence of suicide than in groups of nonphysicians controlled for known variables, including pre-existing behavioral illness.2 This is not a problem we should ignore.

Talking about burnout and depression is discouraged as early as the first year of medical school. In our rush to build a professional core of values, including self-sacrifice, we might have stigmatized recognition and management of burnout for those already out in practice. Today’s medical schools and residencies are actively talking about the signs of burnout and providing tools to recognize and address it as an occupational risk.3

When we think about burnout in ourselves or in a colleague, the signs of its presence probably won’t register for us at first, unless we have intentionally learned to recognize them. Like a subtle diagnosis, it is time for us as practicing physicians to learn to see the patterns in ourselves that, taken together, identify the burnout we have probably already normalized in ourselves and our colleagues. Signs can include a persistent dissatisfaction with job duties or a lack of enjoyment in our work. Maslach calls this a “lost meaning or significance of our work.”4 A second sign is depersonalization of our patients. We might tend to see them as cases or interruptions rather than as individuals with a need we are prepared to address. A third sign is emotional exhaustion that affects our work–life balance. We might find ourselves disengaging from our organization, not being as invested as before, missing meetings, and avoiding committee participation. At home, we can become distant and less engaged with the people who normally balance us and bring us pleasure to be around.

Above all, physicians tend to protect their craft, their livelihood, and their powerful source of identity—their medical or surgical practice. They show up day after day and strive for normalcy, even when they are emotionally crushed and depleted on the inside. This is admirable, but it also can mask the presence of need that could be addressed if it were recognized.

Healthcare workforce burnout carries risks for others as well. Burnout in physicians affects their patients and their host institutions through a reduction in the quality and productivity of their work. In one study, a 16-percent drop in patient satisfaction scores characterized a burnout state in their physicians.5 Surgeons who are burnt out reported an 11-percent increase in medical errors, and their patients had longer postdischarge recovery times.6

Your organization may or may not realize that some of their quality outcomes are being affected by physician or healthcare workforce burnout. It’s important that we, as physicians, understand this connection and begin to bring up the need for change in the health systems where we work and provide leadership.

“Resilience is the ability to adjust to changing stress while maintaining good work quality and outcomes.”

A new understanding of physician wellness describes it not as an end state but as a process in which positive and negative influences continuously build or weaken physician well-being. And contrary to what we might imagine, external factors—the way your corporation or health system creates the context for physician and nurses—is more a contributor to your well-being than solely working on your own internal resilience; in fact, internal and external factors are complementary in producing wellness. The level of physician engagement with achieving quality, compensation systems that favor over-adherence to regulatory statutes, and use of the electronic health record (EHR) that shifts clerical work to doctors have been shown to affect physician well-being.

The work conditions we take for granted in a healthcare system can contribute to burnout—things that could be recognized and changed, improving the wellness of everyone working in that system. Modern health system solutions, while addressing cost and quality, have also resulted in disruption to the known physician drivers of well-being and motivation. Physicians are motivated intrinsically by autonomy (time spent with the patient), achieving personal competence in patient care (which might not be reflected in compliance with targeted metrics), and experiencing relatedness (being valued and recognized in giving the patient time and support). When reconfigured health systems fail to align with these physician values and motivators, there is a loss of physician well-being.8,9

“The qualities that make people good physicians are a double-edged sword. It’s those who are most dedicated to their work who are at greatest risk to be most consumed by it.”10

“So how do I stay resilient?”

Learning to recognize and manage one’s own wellness or resilience is now being taught to medical and surgical residents as part of their medical skill training. We who are already in practice should see learning to recognize our own emotional state of burnout and knowing what we need to do to become and stay well and productive as a part of our own continuing medical education. In my own work as a practicing physician and residency educator, I have found that anyone can learn to recognize and address contributors to our well-being. What’s more, you and I can, by modest effort, change the trajectory of how our healthcare organizations think about and address physician well-being. Let’s look at three things every one of us can do to impact our own resilience and help our organization create the culture of wellness.

Step One: Self-care—Become aware of your own current physical, mental, and emotional state.

As physicians, we need to take our own advice and become aware of our current state of health. We won’t be sacrificing for patients very long if we don’t learn what we ourselves need to favor resilience and make the needed changes.

Tools can help us be more objective about our current overall health. In our institution we started by encouraging all the physicians in our group, along with our residents, to download the free My Well-Being Index app from the Apple or Android stores and to take the one-minute survey. This validated tool developed by the Mayo Clinic can accurately score your own wellness and compare it to thousands of working physicians. Its real strength lies in the three-minute resources available in the app and keyed to your score and its ability to track your wellness over time. Your answers are confidential and useful in becoming aware of how you and your work environment are interacting and the effect that has on your interface with home or life outside of medicine. This is called your work–life balance.

Step Two: Talk about wellness with colleagues.

Now that you know your wellness score, take the next step and bring it up informally with colleagues and younger learners. At lunch or after clinical conference, share your wellness score and your initial thoughts about how you will respond. We circulated a pocket card to clinical leaders detailing talking points on wellness so they would know how to bring up the topic in a natural way with colleagues. This conversation breaks the professional stigma of never discussing burnout and begins the process of creating a culture that promotes physician well-being. Never underestimate the importance of a colleague talking about their own wellness and working on change.

Step Three: Bring up wellness as a quality indicator at your institution or healthcare organization.

Do you want to see a culture of wellness spring up at your healthcare organization? Use some of the references mentioned in this article to become familiar with talking points about the benefits of wellness among healthcare professionals. Bring those along to your next committee meeting for quality improvement or residency education meeting. Ask the group, “What are we doing to measure and improve physician wellness?” In our organization, that question led to an institutional change.

“Yes, something’s wrong, Tricia. But there is help and a way forward.”

Tricia, the surgeon with burnout we met early on, overheard a colleague talking about his wellness score. Later, she privately completed a survey showing her profound level of burnout. “I guess I didn’t know how bad I was,” she told a physician friend and mentor, who was trained to provide “Psychologic First Aid” (a lay person approach to support available for free through Johns Hopkins University).11 She chose to meet with a wellness counselor and made several key changes to her schedule based on more realistic expectations. Months later, she is an advocate for wellness at her institution.

You and I can join Tricia in this work. It’s critical to our own joy as physicians, our patient’s care, and to our institution’s culture that we do.

References

- Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps GJ, et al. Burnout and career satisfaction among American surgeons. Ann Surg. 2009;250(3):463–471.

- Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Dyrbye L, et al. Special report: suicidal ideation among American surgeons. Arch Surg. 2011;146(1):54–62.

- Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Commentary: medical student distress: a call to action. Acad Med. 2011;86(7):801–803.

- Maslach Burnout Inventory—human services survey for medical professionals. Results from Summa Health GMEC 2017–2018.

- Burnout measured by degree of emotional exhaustion. Advisory Board: Medical Group Strategy Council.

- Burnout measured by degree of depersonalization. Advisory Board: Medical Group Strategy Council.

- West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, Shanafelt TD. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;388(10057):2272–2281

- Hartzband P, Groopman J. Physician burnout, interrupted. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(26):2485–2487.

- Gagné M, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and work motivation. J Organiz Behav. 2005;26:331–362.

- Shanafelt T. 2016 AMA Interim Meeting.

- Coursera website. Psychological first aid. https://www.coursera.org/lecture/psychological-first-aid/full-simulation-video-xvcxb. Accessed 9 Sept 2021.

Category: Past Articles, Perspectives