Alarming Increase in Malpractice Claims Related to Wernicke’s Encephalopathy Post Bariatric Surgery: An Alert to Monitor for Thiamine Deficiency

by Eric DeMaria, MD, FACS, FASMBS, and Christa Trigilio-Black, PA-C

by Eric DeMaria, MD, FACS, FASMBS, and Christa Trigilio-Black, PA-C

Dr. DeMaria is Bariatric Surgeon, Bon Secours General Surgery at St. Mary’s Hospital, Richmond, Virginia; President-elect, American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. Dr. Trigilio-Black is Bariatric Surgery, Bon Secours Surgical Specialists, Suffolk, Virginia; Integrated Health Executive Council, Member-at-Large, American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery

Funding: No funding was provided for this article.

Disclosures: The authors reports no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this manuscript.

Bariatric Times. 2018;15(7):8–9.

Introduction

Texas Medical Liability Trust (TMLT), a malpractice carrier in Texas, recently published an alert1,2 stating that they have observed an alarming increase in the number of claims filed related to Wernicke’s encephalopathy (WE) following bariatric surgery. In the following case, which was not a TMLT case, a lawsuit was filed in Texas against the healthcare professionals caring for a patient, alleging failure to administer thiamine.

Case Vignette

A 35-year-old woman presented to the hospital with complaints of vomiting and dehydration that began one month after a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) procedure. She sought treatment from her surgeon, who discovered an anastomotic stricture and successfully performed endoscopic dilation. Despite the procedure, the patient continued to experience vomiting and was unable to keep down any supplemental nutrients, food, or liquid.

Shortly thereafter, she was admitted to the hospital where she was diagnosed with a variety of problems, including dehydration, persistent vomiting, and malnutrition. She was made nil per os (NPO), though for nine days following admission to the hospital, she was unable to retain any kind of vitamin or nutrient.

Two days after admission, a registered dietitian categorized her as high risk for malnutrition and recommended that she receive total parenteral nutrition (TPN), which was not started. As her 12-day stay at the hospital continued, she began developing several worrisome symptoms, many of which suggested neurological causes, including tingling, fixed gaze, hearing impairment, dizziness, weakness, difficulty walking, altered gait, and nystagmus. The patient was discharged home, although she continued to have vision issues, dizziness, headaches, vomiting, altered gait, and weakness. Within one week of her discharge, she was back in the hospital suffering the same symptoms but also with the new onset of delirium, and she became obtunded. During the second hospital stay, she continued to decline and eventually became unresponsive for a period of time.

The patient was moved to a nursing home, where she displayed impaired short-term memory and inability to walk or stand and was mobile only by wheelchair. She was unable to care for herself or for her 11-year-old daughter.

A medical malpractice suit was filed in the above case. The plaintiff alleged that the patient was catastrophically and permanently injured as a result of the medical staff’s failure to administer thiamine. At trial, expert testimony concluded that the patient suffered from WE, a serious neurological disorder caused by thiamine deficiency that is characterized by confusion, inability to coordinate voluntary movement, eye abnormalities, memory loss, and other mental deficits. The plaintiff experts argued the standard of care in this case required that a patient after receiving bariatric surgery who is persistently vomiting should receive thiamine immediately upon admission to prevent this permanent condition.

The jury returned a verdict in favor of the patient and held that the attending physician and his employer were negligent and liable for malpractice. The patient was awarded $14.2 million in damages.

Risk Management Considerations

It is important to recognize that WE and beriberi are neurologic complications resulting from vitamin B1/thiamine deficiency. Both of these complications are 100-percent preventable if adequate thiamine supplementation is ensured. Even when the patient is already experiencing some or all of the characteristic neurologic changes, immediate administration of therapeutic doses of thiamine can result in complete resolution of those symptoms if given within the first 24 to 48 hours of onset.

Malpractice claims related to the development of WE or beriberi typically involve allegations that care providers deviated from the standard of care in terms of both preventing and/or urgently treating the early presentation of signs of vitamin B1/thiamine deficiency. There are multiple scenarios that can contribute to the development of WE and beriberi in a patient following bariatric surgery, including the following:

- Insufficient monitoring of thiamine levels in patients following bariatric surgery

- Inadequate treatment of nausea and vomiting that prevents patients being able to tolerate their oral vitamin supplements

- Failure to identify a patient at risk for thiamine deficiency due to intolerance of oral intake who will require high doses of thiamine in order to prevent WE

- Failure to identify when a patient, who is taking adequate oral thiamine, is not absorbing the vitamin due to vomiting and will require parenteral thiamine to prevent WE

- Failure to identify when a patient might require alternate routes of nutrition and hydration (J-tube or TPN)

- Failure to identify when a patient with visual disturbances, cognitive changes, motor impairments, gait disturbance (often reported simply as “dizziness”), and/or paresthesias and peripheral neuropathies might have the onset of WE or beriberi due to thiamine deficiency and will be requiring immediate, empiric parenteral thiamine supplementation without waiting for blood vitamin B1 levels to be reported

- Failure to identify when, following bariatric surgery, a patient who is having difficulty tolerating oral intake and is having new onset neurologic symptoms, including visual disturbances, cognitive changes, motor impairments, and/or paresthesias that might come and go and vary in severity should be considered vitamin B1/thiamine deficient and be treated empirically.

- Failure to administer thiamine, due to delays in obtaining blood levels from the laboratory, in a patient who might have WE

- Insufficient knowledge to understand that, when dealing with potential B1/thiamine deficiency, the administration of thiamine should not be delayed. “If you think it, give it”—Don’t wait to administer thiamine—it is cheap and innocuous if the patient does not need it in the end.

- Failure to recognize that vitamin B1/thiamine deficiency can result in new onset, and sometimes profound, peripheral neuropathy in the post-bariatric surgery patient and/or too quickly attributing this symptom to the patient’s Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) or the more common vitamin B12 deficiency.

It is important to note that bariatric surgeons are typically the primary defendant in a malpractice suit brought by a patient who has had bariatric surgery and is suffering from WE, even when other healthcare providers are also named as defendants. In fact, nonsurgeon physicians have occasionally used the defense that it is primarily the duty of the treating bariatric surgeon as the relevant specialist who best understands complications of bariatric surgery and who has the primary responsibility to diagnose and treat nutritional deficiencies caused by the bariatric surgery procedure.

The Key Facts about THIAMINE deficiency: Bariatric “Beriberi”3,4

Thiamine is a water-soluble B vitamin (vitamin B1) used by the body for energy production. The biologically active form, thiamine pyrophosphate, acts as a coenzyme in carbohydrate metabolism. The body cannot synthesize thiamine and can only store 30mg, making the human body at risk for quick depletion when nutritional needs are not met. Several contributing factors can exacerbate thiamine deficiency, including alcohol use, bariatric surgery, vomiting, diarrhea, or inadequate nutritional intake. Obesity itself can also be considered an independent risk factor.

The daily recommended dietary allowances (RDAs) of thiamine sufficient to prevent thiamine deficiency in people with normal thiamine levels is 1.2mg per day for men 14 years and older and 1.1mg per day for women over 18 years of age. Adequate thiamine supplementation is found in the form of most standard multivitamin tablets available over the counter, typically 1.5mg per tablet.

A patient is susceptible to thiamine deficiency at any time after bariatric surgery, but especially during the first six months when rapid weight loss occurs. Early signs and symptoms of deficiency are often nonspecific and vague, such as fatigue, anorexia, nausea, poor memory, sleep disturbance, and lower extremity paresthesia. If the vitamin B1/thiamine deficiency develops suddenly and is profound, progression to more debilitating and severe symptoms can occur rapidly in the form of WE (e.g., vomiting, nystagmus, ataxia, progressive mental impairment).

If treatment is delayed at this stage, progression to Korsakoff syndrome (severe cognitive impairment) can result, the symptoms of which are often irreversible. If the vitamin B1/thiamine deficiency develops gradually or recurs chronically, often related to waxing and waning tolerance of oral intake, the patient is more likely to develop beriberi/peripheral neuropathy, the consequences of which can also be profound and disabling. Aggressive treatment is warranted for beriberi as well.

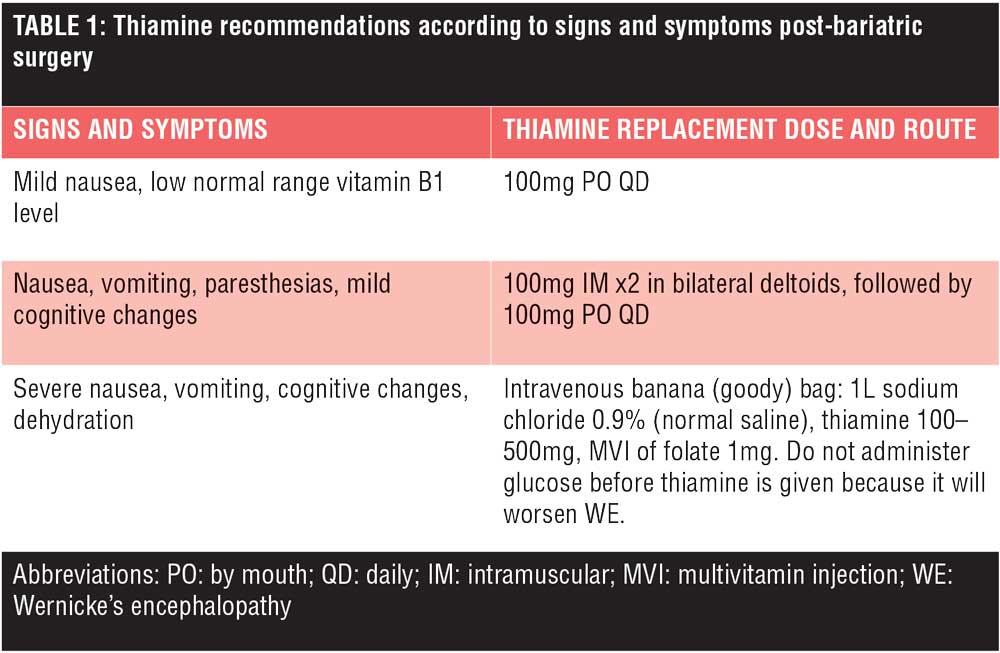

Thiamine is nontoxic, even in high concentrations; therefore, it is most practical to replace thiamine empirically in any patient with suspected thiamine deficiency, even in the absence of a blood test result to confirm the diagnosis. If at all possible, the healthcare provider should obtain a blood sample for vitamin B1 level before administering parenteral thiamine only if it will delay administration of thiamine by a few minutes. The goals of pharmacotherapy are to reduce morbidity and progression of complications, and, therefore, prompt replacement is critical. If a patient is symptomatic, parenteral replacement is initially indicated with transition to oral replacement once symptoms improve (Table 1).

It is recommended that parenteral thiamine via the intramuscular route be available in the bariatric office setting and used liberally. In addition, all post-bariatric surgery patients treated for nausea/vomiting/dehydration in hospital emergency departments, infusion centers, or as inpatients, should be initially rehydrated with an intravenous “banana (goody) bag” containing 100–500mg of thiamine and multivitamin injection (MVI) of folate 1mg. Do not administer glucose before thiamine is given because this will worsen WE. High doses of intravenous thiamine (e.g., 500mg IV on prescription [TID] for 2 to 3 days) can reverse some of the neurologic changes of WE and might be appropriate in suspected cases due to the detrimental consequences of thiamine deficiency undertreatment.5

Warning Issued by TMLT

All healthcare professionals should be aware of the risk factors and symptoms associated with nutritional deficiencies, particularly when treating patients who have had bariatric surgery, to minimize any adverse effects. Early recognition of symptoms is important for all providers caring for this patient population.

References

- McNeil M. Failure to monitor vitamin levels after bariatric surgery. 2017. The Reporter. Texas Medical Liability Trust. http://resources.tmlt.org.s3.amazonaws.com/PDFs/Reporter/GeneralSurgery2017.pdf. Accessed 27 Jun 2018.

- Texas Medical Liability Trust. Wernicke’s encephalopathy after bariatric surgery (slide show). May 17, 2017. https://www.slideshare.net/tmlt/wernickes-encephalopathy-after-bariatric-surgery. Accessed 27 Jun 2018.

- Aasheim ET. Wernicke encephalopathy after bariatric surgery: a systematic review. Ann Surg. 2008;248(5):714–720.

- Kröll D, Laimer M, Borbély YM, et al. Wernicke encephalopathy: a future problem even after sleeve gastrectomy? A systematic literature review. Obes Surg. 2016;26(1):

205–212. - Thomson AD, Cook CC, Touquet R, Henry JA. The Royal College of Physicians report on alcohol: guidelines for managing Wernicke’s encephalopathy in the accident and Emergency Department. Alcohol. 2002;37(6):513–521.

Category: Commentary, Past Articles