The Role of Facebook Support Groups in Bariatric Surgery

by Spyridon Giannopoulos, MD, and Dimitrios Stefanidis, MD, PhD

Drs. Giannopoulos and Stefanidis are with the Department of Surgery, Indiana University School of Medicine in Indianapolis, Indiana.

Funding: No funding was provided for this article.

Disclosures: Dr. Stefanidis received research support from Becton Dickinson and Intuitive. Dr. Giannopoulos has no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Bariatric Times. 2022;19(10):12–14.

Abstract

Social support plays a critical role in helping patients undergoing bariatric surgery achieve higher postoperative weight loss and improved satisfaction. However, the recent restrictions of the COVID-19 pandemic have challenged traditional support groups, leading to the suspension of in-person meetings and severely limiting patient access to this important resource. As a consequence, a shift toward web-based healthcare resources has occurred, making Facebook a popular online platform for support groups for several chronic conditions. In this context, Facebook support groups offer a tool to overcome the difficulties of conventional social support methods and concurrently deliver high-quality health support. Several studies have demonstrated bariatric Facebook groups to be effective in providing educational, emotional, and social support to their members. To maximize the benefits of Facebook support groups and improve patient adherence to bariatric surgeon recommendations in the long term, Facebook support groups should be monitored frequently by healthcare facilitators filtering inappropriate or disrespectful comments and posts. However, there is limited guidance on developing content, effective engagement, and communication strategies for Facebook groups because of the differences in communication mechanisms between in-person and social media support groups. In this article, we discuss our experience with a monitored bariatric surgery patient Facebook group, review the available literature, and provide recommendations for the optimal patient engagement.

Keywords: Social support groups, Facebook, bariatric surgery

In light of the increasing prevalence of obesity in the United States (US), the number of bariatric surgeries performed has been growing, reaching 256,000 cases in 2019.1,2 Unfortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic has led to a temporary decrease in the number of bariatric operations, due to the cancellation of millions of elective surgical procedures.3 At the same time, it has created an environment with decreased access to bariatric care and treatment of obesity-related comorbidities. Despite that, bariatric surgery remains a first-line obesity treatment, as it has been shown to produce significant long-term weight loss4 and a higher remission rate of obesity-related comorbidities, such as Type 2 diabetes mellitus, compared to nonsurgical treatment options.5,6

Nevertheless, patients exhibit a great variability of outcomes after bariatric surgery, depending on several factors, including both patient- (e.g., age, preoperative body mass index [BMI], hypertension, total comorbidities, depression/anxiety, previous abdominal surgery)7–9 and population-related characteristics.10 Social support plays a critical role in helping patients undergoing bariatric procedures achieve higher postoperative weight loss and increased satisfaction.11–15 The American Society of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) recommends that all bariatric patients attend support groups postoperatively and mandates that all centers accredited by the Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program (MBSAQIP) offer professionally supervised support groups.16,17

Support groups after bariatric surgery have been associated with greater weight loss;12 they cover many areas of interest for the patients (e.g., adherence to diet, physical activity, lifestyle changes, emotional and informational assistance regarding surgery) and are provided by a wide range of professionals in multiple settings (e.g., nonprofit advocacy organization, clinic, hospital or community organization, independent organization) and formats, including face-to-face meetings, teleconferences, and online communities.12,18 While the traditional in-person support groups have many benefits for bariatric patients, they have been challenged by accessibility-related limitations, such as fixed times and locations offered to patients. Furthermore, limitations on the number of participants, mobility and transportation issues associated with obesity, long distances from bariatric centers, and fear of stigmatization by healthcare professionals decrease the number of bariatric patients willing to participate in these groups.19–21 Moreover, the recent restrictions of the COVID-19 pandemic led to suspension of in-person support groups and face-to-face sessions, increasing uncertainty and mental health distress, which created difficulties for bariatric patients controlling their weight.22,23

In this context, online-based social support groups address many of these limitations,24 similar to telemedicine services offered to patients with limited access to healthcare resources.25,26 As such, online social support groups have increasingly been implemented in the post-bariatric surgery setting, giving patients the opportunity to ask questions, give recommendations, and share their experiences with their peers.27 They can be divided into synchronous (e.g., Zoom groups), asynchronous (e.g., online forums), or hybrid support groups.28 For instance, Facebook groups are generally considered an asynchronous support method; however, sometimes the provided assistance can be synchronous (e.g., live Facebook stream).29,30

Social media support groups (e.g., Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube, online forums) allow members to easily access information at any time from any location, thus avoiding most of the difficulties associated with in-person meetings. This convenience can facilitate more frequent participation from patients, and a great degree of flexibility is present. The content can be shared in different ways depending on the design and goal of the support group (e.g., open, private, closed) without losing the advantage of providing case-specific feedback to patients. In other words, by choosing what type of group patients join, they can control who will have access to their posts and are able to choose how much information they want to communicate. As such, groups that focus on patient-specific advice would benefit from a private or closed approach. In contrast, groups emphasizing diet, lifestyle changes, or patient motivation would have greater efficacy if accessed by more people, which is the case with open social support groups. Additionally, a certain degree of anonymity or privacy is essential to create an open and nonjudgmental atmosphere and help individuals feel more comfortable sharing sensitive or personal issues. The patients can determine their level of privacy and thus avoid inconvenient situations, which could otherwise lead to quitting support groups.

Several social media platforms have extensive educational material and content related to obesity. However, Facebook seems to be the most popular and has already been described as a useful tool to exchange health-related knowledge between patients and healthcare providers in a nonjudgmental manner.31 A recent study showed that 84 percent of bariatric patients follow support groups on Facebook.32 Similar Facebook groups (public or supervised by professionals) also exist for other conditions that require support and situation-specific information, such as pregnancy, general chronic conditions, diabetic foot care, hypertension, dialysis/renal issues, multiple sclerosis, and diabetes.33–40 Several centers have incorporated Facebook support groups in the follow-up care for bariatric patients, allowing patients to join the community during their supervised weight loss period and receive valuable information shared by experienced peers or healthcare professionals.

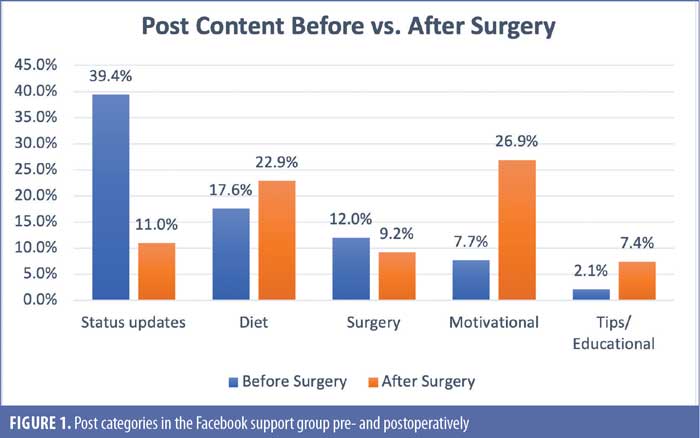

A recent thematic analysis of such a group, conducted by our research team, reported the most common themes in the posts of an organization-supervised bariatric Facebook support group.41 As expected, the content was related to questions or advice around bariatric surgery, motivation, diet, physical activity, and patient status updates. Interestingly, the study also showed different needs for information between pre- and postoperative patients. Specifically, preoperative patients sought information related to diet (17.6%) and surgery (12%), while 39.4 percent of these participants provided updates of their status.41 In contrast, postoperative patients tended to post motivational (26.9%) or educational content (7.4%), questions regarding diet (22.9%), and limited personal status updates (11%) (Figure 1). This variation in content might reflect an alteration in the behavior of post-bariatric surgery patients to avoid weight regain. Acknowledging the different needs of pre- and post-bariatric surgery patients has led some programs to offer different support groups before and after bariatric surgery. However, it is not known whether having separate social support groups for pre-and postoperative patients would have a potential added benefit. The advantage of such a separation would be to focus specifically on areas of interest for pre- and postoperative patients, respectively. In this way, irrelevant content would decrease significantly and more details could be provided and analyzed in depth. However, this would reduce the peer-to-peer contact and interaction, with unknown effects on the effectiveness of the assistance provided. Therefore, future research efforts should focus on this fundamental aspect of Facebook support groups, which could be a determinant factor for success.

In the same study,41 participants reported that the emotional support and information received through the Facebook group was helpful overall. Notably, the members stated that the support group was a convenient way to help them keep focusing on their goals, get the feeling of being understood, and connect with other people experiencing similar difficulties. Unfortunately, members admitted that the Facebook support group was less effective in certain areas, such as stress relief and adherence to diet. Interestingly, patients reported having an overall benefit from the group even without actively seeking advice or posting questions. This finding aligns with previous studies reporting that even patients who do not participate in discussions or share information and use the online support groups passively also seem to benefit from the experiences and material posted.40 Despite that, the group administrators should direct their efforts to engage all group members by using creative initiatives to maximize emotional support, informational support, and social companionship. Such strategies include, but are not limited to, posting educational videos by experts, polls, surveys, quizzes, motivational quotes, and challenges; organizing storytelling events; using Facebook live videos; and recommending users to activate their group notifications.

A study by Koball et al43 investigating Facebook groups thematically after bariatric surgery showed that information related to diet was the most discussed topic, making up 35 percent of posts. However, concern was raised, as it was found that over half of the posts contained inaccurate or incomplete information related to obesity. Specifically, seven percent of posts did not comply with ASMBS nutritional guidelines or dietitian recommendations, 22 percent included some imprecise information, and it was not possible to determine the accuracy of 24 percent of posts.42,43 Considering that many bariatric patients search the internet to find health-related information and perceive online sources as the same or higher quality information than a healthcare provider, the authors suggested this could harm bariatric patients.44,45 As such, they asked for caution when recommending the use of bariatric Facebook support groups. Other studies have shared similar concerns about the safety and dangers of web-based support groups in various fields, such as eating disorders, highlighting the need for safe and effective integration of technological tools in clinical services.46

Nevertheless, it has been shown that closed bariatric Facebook support groups, accessible only by pre- or post-bariatric surgery patients and monitored by healthcare providers and other specialists, can help avoid inaccurate information while maintaining the effectiveness and assistance provided by the group.41 The design of such a successful private support group for bariatric patients was recently described by our group.41 Patients voluntarily enrolled in the Facebook support group during their first bariatric consultation. Healthcare facilitators monitored the group daily and excluded inappropriate comments and posts. The support group consisted only of program patients and specialized staff members responsible for maintaining high-quality, evidence-based responses to patients’ questions, free of intolerable behaviors or inaccurate information. However, the program invested a significant amount of time and effort to reach this level of quality and offer a highly protected environment.

This concept of a professionally supervised social support group inspired trust and confidence in the group members, affecting the content of information shared by users.41 A higher percentage of pictures posted before and after bariatric surgery (42%) were found in a professionally supervised Facebook group offered by a bariatric center, compared to other Facebook groups (18.5%).41 The reason behind this might be that the supervision of professional facilitators (e.g., bariatric surgeon or clinician, nurse, social worker or psychologist) caused members to feel protected and safe uploading personal information and experiences. This, in turn, had positive benefits for the group members, as it promoted the undistracted, peer-to-peer exchange of experiences and encouraged the participants to ask questions on sensitive topics freely (e.g., weight regain, side effects of surgery, talking openly about feelings and challenges). In contrast, nonsupervised social support groups might cause reluctance and mistrust between members, inhibiting the supportive role of these platforms.46

Conclusion

In view of the above, Facebook support groups offer a great tool to overcome the difficulties of conventional social support methods and concurrently deliver high-quality health support. The bariatric patient population seems to be an ideal group to benefit from Facebook social support, as obesity is still perceived as a social stigma, which can affect the participation of bariatric patients. Several studies based on patient feedback have demonstrated bariatric Facebook groups to be effective in providing educational, emotional, and social support to their members. To maximize the benefits of Facebook support groups, they should be monitored frequently by healthcare facilitators filtering inappropriate or disrespectful comments and posts. However, Facebook support groups should be used in conjunction with the conventional in-person groups, as some patients might not be familiar with using online platforms or have no internet access. Online support groups adjunctive to in-person sessions are not only perceived positively from the patient, but also seem to improve adherence in the long term.47

Finally, creating online support groups through social media can be challenging, as the communication mechanisms differ significantly from in-person groups. Although a significant number of studies provide information on how to organize in-person support groups, there is limited guidance on developing content, effective engagement, and communication strategies for Facebook groups.48 Therefore, more input from members of online bariatric groups and further thematic analyses are warranted.

References

- Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and severe obesity among adults: United States, 2017–2018. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db360.htm. Accessed 11 Apr 2022.

- American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. Estimate of bariatric surgery numbers, 2011–2019. 2021. https://asmbs.org/resources/estimate-of-bariatric-surgery-numbers. Accessed 11 Apr 2022.

- COVIDSurg Collaborative. Elective surgery cancellations due to the COVID-19 pandemic: global predictive modelling to inform surgical recovery plans. Br J Surg. 2020;107(11):1440–14449.

- O’Brien PE, Hindle A, Brennan L, et al. Long-term outcomes after bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of weight loss at 10 or more years for all bariatric procedures and a single-centre review of 20-year outcomes after adjustable gastric banding. Obes Surg. 2019;29(1):3–14.

- Gloy VL, Briel M, Bhatt DL, et al. Bariatric surgery versus non-surgical treatment for obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2013;347:f5934.

- Ricci C, Gaeta M, Rausa E, et al. Early impact of bariatric surgery on type II diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia: a systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression on 6,587 patients. Obes Surg. 2014;24(4):522–528.

- Cadena-Obando D, Ramírez-Rentería C, Ferreira-Hermosillo A, et al. Are there really any predictive factors for a successful weight loss after bariatric surgery? BMC Endocrine Disorders. 2020;20(1):20.

- Contreras JE, Santander C, Court I, Bravo J. Correlation between age and weight loss after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2013;23(8):1286–1289.

- Nelbom B, Naver L, Ladelund S, Hornnes N. Patient characteristics associated with a successful weight loss after bariatric surgery. Bariatr Nurs Surg Patient Care. 2010;5(4):313–319.

- Ibrahim AM, Ghaferi AA, Thumma JR, Dimick JB. Variation in outcomes at bariatric surgery centers of excellence. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(7):629–636.

- Orth WS, Madan AK, Taddeucci RJ, et al. Support group meeting attendance is associated with better weight loss. Obes Surg. 2008;18(4):391–394.

- Livhits M, Mercado C, Yermilov I, et al. Is social support associated with greater weight loss after bariatric surgery? A systematic review. Obes Rev. 2011;12(2):142–148.

- Lauti M, Kularatna M, Pillai A, et al. A randomised trial of text message support for reducing weight regain following sleeve gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2018;28(8):2178–2186.

- Stromberg SE, Gonzalez-Louis R, Engel M, et al. Pre-surgical stress and social support predict post-surgical percent excess weight loss in a population of bariatric surgery patients. Psychol Health Med. 2020;25(10):1258–1265.

- Tymoszuk U, Kumari M, Pucci A, et al. Is pre-operation social connectedness associated with weight loss up to 2 years post bariatric surgery? Obes Surg. 2018;28(11):3524–3530.

- Pratt GM, McLees B, Pories WJ. The ASBS Bariatric Surgery Centers of Excellence program: a blueprint for quality improvement. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2006;2(5):497–503; discussion 503.

- Mechanick JI, Youdim A, Jones DB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the perioperative nutritional, metabolic, and nonsurgical support of the bariatric surgery patient–2013 update: cosponsored by American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, the Obesity Society, and American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2013;9(2):159–191.

- Hameed S, Salem V, Tan TM, et al. Beyond weight loss: establishing a postbariatric surgery patient support group–what do patients want? J Obes. 2018;2018:8419120.

- Peytremann-Bridevaux I, Santos-Eggimann B. Health correlates of overweight and obesity in adults aged 50 years and over: results from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). Obesity and health in Europeans aged > or = 50 years. Swiss Med Wkly. 2008;138(17–18):261–266.

- Kuo LE, Simmons KD, Kelz RR. Bariatric Centers of Excellence: effect of centralization on access to care. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;221(5):914–922.

- Anderson DA, Wadden TA. Bariatric surgery patients’ views of their physicians’ weight-related attitudes and practices. Obes Res. 2004;12(10):1587–1595.

- Youssef A, Cassin SE, Wnuk S, et al. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on bariatric patients’ self-management post-surgery. Appetite. 2021;162:105166.

- Ahmed B, Altarawni M, Ellison J, Alkhaffaf BH. Serious impacts of postponing bariatric surgery as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic: the patient perspective. J Patient Exp. 2021;8:23743735211008282.

- Yeo C, Ahmed S, Oo AM, et al. COVID-19 and obesity–the management of pre- and post-bariatric patients amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Obes Surg. 2020;30(9):3607–3609.

- Salwen-Deremer JK, Lauretti JM, et al. Remote unaffiliated presurgical psychosocial evaluations: a qualitative assessment of the attitudes of ASMBS members. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2021;17(6):1182–1189.

- Coldebella B, Armfield NR, Bambling M, et al. The use of telemedicine for delivering healthcare to bariatric surgery patients: a literature review. J Telemed Telecare. 2018;24(10):651–660.

- Koball AM, Jester DJ, Domoff SE, et al. Examination of bariatric surgery Facebook support groups: a content analysis. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13(8):1369–1375.

- Sockalingam S, Leung SE, Cassin SE. The impact of coronavirus disease 2019 on bariatric surgery: redefining psychosocial care. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2020;28(6):1010–1012.

- Thrul J, Belohlavek A, Hambrick D, et a;. Conducting online focus groups on Facebook to inform health behavior change interventions: two case studies and lessons learned. Internet Interv. 2017;9:106–111.

- Grainger R, White B, Morton C, Day K. A health professional-led synchronous discussion on Facebook: descriptive analysis of users and activities. JMIR Form Res. 2017;1(1):e6.

- Adzharuddin NA, Ramly NM. Nourishing healthcare information over Facebook. Soc Behav Sci. 2015;172:383–389.

- Martins MP, Abreu-Rodrigues M, Souza JR. The use of the internet by the patient after bariatric surgery: contributions and obstacles for the follow-up of multidisciplinary monitoring. Arq Bras Cir Dig. 2015;28(Suppl 1):46–51.

- Harpel T. Pregnant women sharing pregnancy-related information on Facebook: web-based survey study. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(3):e115.

- Stellefson M, Paige S, Apperson A, Spratt S. Social media content analysis of public diabetes Facebook groups. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2019;13(3):428–438.

- De la Torre-Díez I, Díaz-Pernas FJ, Antón-Rodríguez M. A content analysis of chronic diseases social groups on Facebook and Twitter. Telemed J E Health. 2012;18(6):404–408.

- Abedin T, Al Mamun M, Lasker MAA, et al. Social media as a platform for information about diabetes foot care: a study of Facebook groups. Can J Diabetes. 2017;41(1):97–101.

- Al Mamun M, Ibrahim HM, Turin TC. Social media in communicating health information: an analysis of Facebook groups related to hypertension. Prev Chronic Dis. 2015;12:E11.

- Ahmed S, Haines-Saah RJ, Afzal AR, et al. User-driven conversations about dialysis through Facebook: a qualitative thematic analysis. Nephrology (Carlton). 2017;22(4):301–307.

- Tan J, Sesagiri Raamkumar A, Wee HL. Digital support for renal patients before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: examining the efforts of Singapore social service agencies in Facebook. Front Big Data. 2021;4:737507.

- Steadman J, Pretorius C. The impact of an online Facebook support group for people with multiple sclerosis on non-active users. Afr J Disabil. 2014;3(1):132.

- Athanasiadis DI, Roper A, Hilgendorf W, et al. Facebook groups provide effective social support to patients after bariatric surgery. Surg Endosc. 2021;35(8):4595–4601.

- Parrott J, Frank L, Rabena R, et al. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery integrated health nutritional guidelines for the surgical weight loss patient 2016 update: micronutrients. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13(5):727–741.

- Koball AM, Jester DJ, Pruitt MA, et al. Content and accuracy of nutrition-related posts in bariatric surgery Facebook support groups. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018;14(12):1897–1902.

- Paolino L, Genser L, Fritsch S, et al. The web-surfing bariatic patient: the role of the internet in the decision-making process. Obes Surg. 2015;25(4):738–743.

- Diaz JA, Griffith RA, Ng JJ, Reinert SE, et al. Patients’ use of the Internet for medical information. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(3):180–185.

- Basterfield A, Dimitropoulos G, Bills D, et al. “I would love to have online support but I don’t trust it:” positive and negative views of technology from the perspective of those with eating disorders in Canada. Health Soc Care Community. 2018 Jul;26(4):604-12.

- Ufholz K. Peer support groups for weight loss. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep. 2020;14(10):19.

- Embuldeniya G, Veinot P, Bell E, et al. The experience and impact of chronic disease peer support interventions: a qualitative synthesis. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;92(1):3–12.

Category: Commentary, Past Articles