Raising the Standard: Time for Medicine to Catch Up to the Public Domain in Conflict of Interest Transparency

by Tara McGraw, DO; Anthony Petrick, MD, FACS, FASMBS; and Dominick Gadaleta, MD, FACS, FASMBS

by Tara McGraw, DO; Anthony Petrick, MD, FACS, FASMBS; and Dominick Gadaleta, MD, FACS, FASMBS

Dr. McGraw is a PGY5 Surgical Resident at Geisinger Wyoming Valley Medical Center in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. Dr. Petrick is Chief Quality Officer, Geisinger Clinic; Director of Bariatric and Foregut Surgery, Geisinger Health System, Danville, Pennsylvania. Dr. Gadaleta is Chair, Department of Surgery, South Shore University Hospital; Director, Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery, North Shore and South Shore University Hospitals, Northwell Health, Manhasset, New York; Associate Professor of Surgery, Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell in Hempstead, New York.

FUNDING: No funding was provided for this article.

DISCLOSURES: The authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Bariatric Times. 2021;18(6):14–15.

“Whenever there is a conflict between universal principals and self-interest, self-interest is likely to prevail.”

-George Soros

Medical device manufacturers and pharmaceutical companies rely on healthcare professionals for development and implementation of new drugs and devices. Clinicians, who have spent careers acquiring the proficiency to direct product development, appropriately expect to be compensated for their time and expertise. However, this relationship creates significant potential for a conflict of interest (COI). Georgetown University ethicist Dr. E.D. Pellegrino described this responsibility stating, “Medicine is a profession, defined, in part, by the obligation to place the interests of the patient, society, and the profession itself ahead of one’s own interests.”1 The difficult question has always been how can we regulate these relationships in a way that promotes the advancement of healthcare without sacrificing patient, societal and professional interests?

High-profile examples of the influence on healthcare policy by clinicians with substantial COI have been widely reported. In September 2018, the chief medical officer of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, resigned after Propublica and The New York Times reported his failure to disclose millions of dollars in payments from pharmaceutical companies. The Times reported that no disclosure was made in 60 percent of papers published, including those in the New England Journal of Medicine and Lancet. The source of the data cited in these reports was the publicly accessible website www.openpayment.cms.gov.2

The problem of COI was critically evaluated in a 2007 study by Campbell et al.3 Physicians in six specialties were surveyed. It was found that 35 percent of physicians received reimbursements for costs associated with professional meetings or continuing education, while 28 percent received payments for consulting, lectures, or enrolling patients in clinical trials.3 Similarly, Zia et al4 studied the 10 highest compensated physicians by the 10 companies with the largest payments reported in open payments in 2015. Fifty-four percent of the general payments received by the authors were relevant to published articles. However, in the relevant publications, the potential COI was disclosed by only 37 percent of authors, and 85 percent had a least one publication without disclosure of COI.4

There is good evidence that, in the United States (US), patient interests are better protected than they have ever been. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) rule entitled, “Transparency Reports and Reporting of Physician Ownership or Investment Interests” is also known as the Physician Payments Sunshine Act, which was instituted with the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010. The Sunshine Act requires CMS to “collect information from manufacturers and group purchasing organizations (GPOs) to report information on their financial relationships with physicians and hospitals.”5

This information has been publicly available since 2013 on the website www.openpayments.cms.gov. All physicians in the US are required to register in the Enterprise Identity Management System using their National Provider Identification (NPI) number as are all pharmaceutical and device manufactures. The site is updated on a 12-month cycle every June 30.6

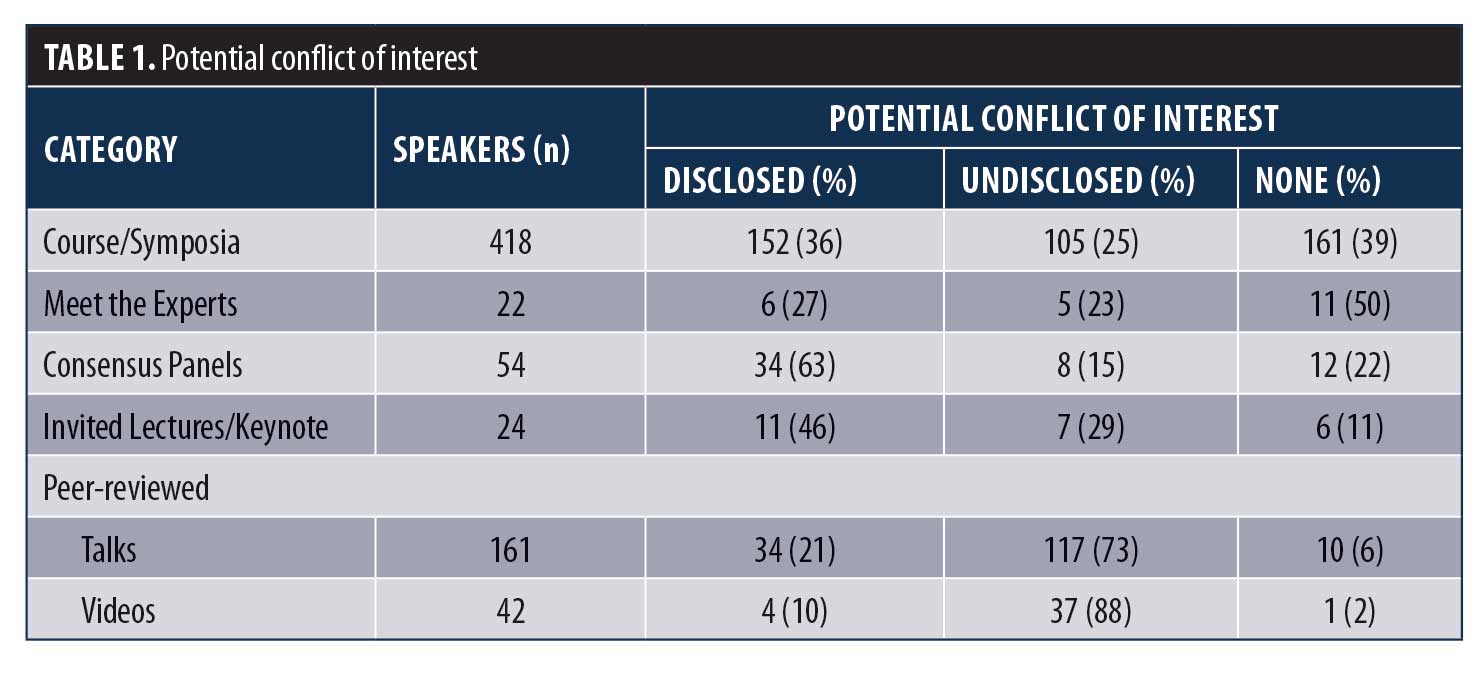

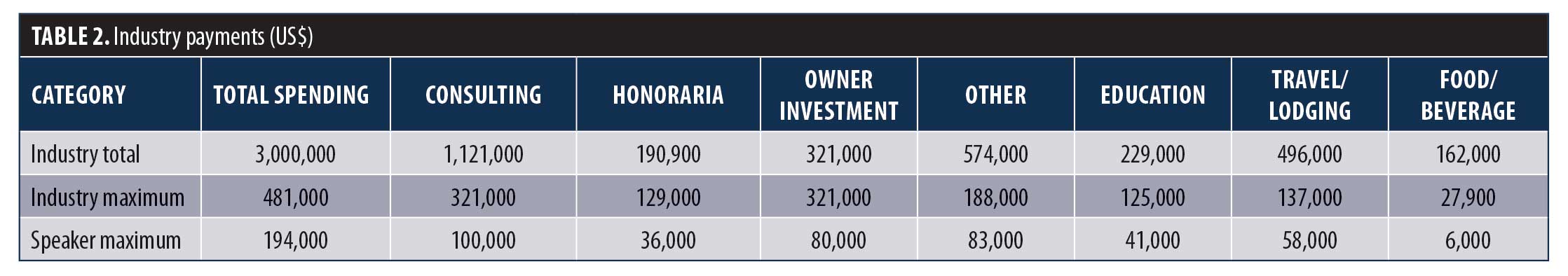

Our group reviewed the titles of all presentations and the names of all moderators, speakers and discussants at American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) or joint ASMBS Speaker sessions from the ObesityWeek 2016 (OW2016) conference schedule. Disclosure forms for all speakers were compared to Open Payments data for 2016. Taxable income was considered as potential COI, but food and travel reimbursements were not. A total of 370 speakers were identified. Based on their presentations, a potential COI was found for 45 percent of speakers (22% disclosed; 23% undisclosed). A potential COI was found in 72 percent of 721 presentations (33% disclosed; 39% undisclosed) (Table 1). A total of 109 companies made payments to speakers totaling $3,000,000 (Table 2).7

Open Payments data has made the exact dollar amounts and types of industry payments available to the public for 6 years, most recently for 2019. In 2019, Ethicon® paid three physicians over $1,000,000,8 Medtronic® paid one physician over $400,000,9 and Intuitive Surgical® paid 13 surgeons over $200,000.10 While the nature of these payments varied considerably, the current system of a general nondisclosure slides or statements is clearly outdated. The general public has access to more COI information than what is disclosed in our meetings and journals. There is no need for the authors to characterize their potential COI. All societies and scientific publications should consider redesigning the disclosure process to include the specific type and amount of compensation for each author. The potential for bias related to COI should be left to reviewers and readers.

References

- Pelligrino, Ed, Thomasma D. Chapter 12. In: The virtues in medical practice. London, UK: Oxford University Press; 1993: 144–144.

- Thomas K, Ornstein C. Top Sloan Kettering cancer doctor resigns after failing to disclose industry ties. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/13/health/jose-baselga-cancer-memorial-sloan-kettering.html. Published September 13, 2018. Accessed September 15, 2018.

- Campbell EG, Gruen RL, Mountford J, et al. A national survey of physician–industry relationships. New Engl J Med. 2007;356:1742–1750.

- Ziai K, Pigaszzi A, Smith BR, et al. Association of compensation from the surgical and medical device industry to physicians and self-declared conflict of interest. JAMA Surgery. 2018;153(11):997–1002.

- Cherla DV, Olavarria OA, Bernardi, K, et al. Investigation of financial conflict of interest

- among published ventral hernia research. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;226(3):230–234.

- Law and Policy. CMS. https://www.cms.gov/OpenPayments/About/Law-and-Policy.html. Published November 28, 2016. Accessed August 15, 2018.

- Open Payments Data. Open Payments Data CMS. https://www.cms.gov/OpenPayments/index.html. Published June 2017. Accessed April 2018.

- ASMBS Abstracts. https://asmbs.org/app/uploads/2019/02/53473_Obesity_Week_ASMBS-Abstracts.pdf. 147–148.

- Ethicon, Inc. OpenPaymentsData. https://openpaymentsdata.cms.gov/company/100000000122. Accessed May 23, 2021.

- Medtronic, Inc. OpenPaymentsData. https://openpaymentsdata.cms.gov/company/100000000106. Accessed May 23, 2021.

- Intuitive Surgical, Inc. https://openpaymentsdata.cms.gov/company/100000005384 Accessed May 23, 2021.

Category: Past Articles, Raising the Standard