Stapler Reload Misfires During Sleeve Gastrectomy: Isolated Events or Cause for Concern?

by George Woodman, MD, FACS, FASMBS; Alexander Wells, BS; and Guy Voeller, MD

Dr. Woodman is with Baptist Memorial Hospital–Memphis in Memphis, Tennessee, and Methodist Hospital Germantown in Germantown, Tennessee. Mr. Wells is a medical student at the University of Tennessee Health Sciences Center in Memphis, Tennessee. Dr. Voeller is with Baptist Health Sciences University in Memphis, Tennessee.

Funding: No funding was provided for this article.

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the contents of this article.

Correspondence: George Woodman, MD, FACS, FASMBS; Email: [email protected]

Bariatric Times. 2023;20(7–8). Published online July 21, 2023.

Abstract

Mechanical staplers are a requirement for advanced laparoscopic bariatric surgery. There is little margin for error, and a misfire during a sleeve gastrectomy can potentially have catastrophic consequences. We present a series of six staple load misfires involving one manufacturer in a 10-month period by an experienced team, which includes a single surgeon and single scrub technician who have together fired a linear stapler over 60,000 times and performed 417 sleeve gastrectomies total during this 10-month period. Prior to this 10-month period we had only a single linear stapler misfire over the previous 14 years.

Keywords: Bariatric surgery, obesity, mechanical staplers, weight loss, MAUDE database

Obesity is a global epidemic, and bariatric surgery is accepted as a common treatment option. Sleeve gastrectomy is now the single most common procedure performed for severe obesity.1–3 Although there are multiple nuances to the surgical technique, the procedure generally requires multiple firings of a linear stapler with a bougie in place.

There are multiple stapler manufacturers with products on the market including, but not limited to, Medtronic, Ethicon, and Intuitive. Our practice has had extensive experience with both Medtronic and Ethicon, but over the last 10 years, we have used exclusively Ethicon staplers (Ethicon, Inc.; Raritan, NJ) due primarily to hospital contracts. We have had excellent results with both manufacturers until recently.

Our surgical team is experienced with multiple bariatric procedures and has performed over 3,400 sleeve gastrectomies, consisting of the same primary surgeon and the same scrub technician for every case. This has been unchanged for more than 20 years. We make this statement to clarify the experience of the team, both overall and with the specific staplers and proper loading of these instruments.

Safety profiles by major stapler manufacturers state very low rates of malfunction.4 We report a significant recent series of stapler reload misfires from a single manufacturer during sleeve gastrectomy.

Description of Procedure

The sleeve gastrectomy involves a longitudinal resection of the gastric fundus, body, and antrum, resulting in a tubularized stomach conduit based on the lesser curve.5 Mobilization of the greater curvature is performed with a harmonic scalpel (Ethicon Endo-Surgery; Cincinnati, OH). This dissection is started 3cm from the pylorus and taken proximally to the angle of His and left crus. A 36 French Ewald tube is advanced into the distal stomach under visualization, and the gastric transection is started 3cm from the pylorus, with care taken to avoid narrowing of the gastric outlet at the incisura. Proximal gastric mobilization and complete fundic excision are performed in all cases.

The Ethicon Echelon Flex™ Powered Plus Articulating Endoscopic Linear Cutter (60mm) with Ethicon Echelon™ Surgical Care Green Staple Loads (2.0mm) and a bioabsorbable staple line reinforcement (SLR) product made of copolymer polyglycolic acid/trimethylene carbonate (GORE® SEAMGUARD® Bioabsorbable Staple Line Reinforcement, WL Gore & Associates; Newark, DE) is used to divide the stomach along the Ewald tube and completed just distal to the esophagogastric junction at the angle of His. Care is taken not to cross staple lines. In our series of sleeve gastrectomy cases, the Ethicon powered stapler was used in all cases.

When a misfire or malfunction occurred, the stapler was replaced, and the subsequent staple firing was performed to better visualize the defect resulting from the misfire. Ethibond suture was used to anchor the defect at each end, and a subsequent 2-0 ethibond suture was run inferiorly from the most superior aspect and tied. We were mindful to minimize narrowing of the gastric conduit. The gastric transection was then completed. Fibrin glue (Ethicon Vistaseal™) was used to cover the staple and suture lines after a misfire but not routinely in every case. The omentum was used to cover the handsewn segment without tension.

We follow manufacturer guidelines and regularly review the instructions for use (IFU) to ensure compliance with our instruments and products. Ethicon powered staplers and green loads are used for all firings. SEAMGUARD is routinely used for all gastric stapler firings. The previous staple line is examined prior to each subsequent firing, making sure that no loose staples are present. The stapler itself is aggressively washed between each firing, ensuring that no tissue or staples are present within the mechanism of the device. Once tissue is compressed, we wait 15 seconds prior to initiating the firing process.

Discussion

Obesity is a worldwide epidemic that will continue to require treatment options, such as bariatric surgery, for the foreseeable future. Surgical staplers and other surgical devices are critical to performing these life-saving procedures in a safe fashion and through minimally invasive techniques.

As surgeons, we rely on these advanced products to perform complex tasks that, in the past, were much riskier and technically demanding and certainly resulted in longer operative times and higher morbidity.6–8 When these typically reliable instruments fail, we must be ready to address the highly frustrating and potentially disastrous situation.

We believe that in our case series, we have minimized variability with a team consisting of a single surgeon, the same experienced assistant surgeon, and the same surgical technician who loads the stapler for every case. Certainly, variability among the operating room personnel increases risk throughout a procedure, particularly when an inexperienced team member is handling staplers. We have eliminated that variable. Our routine has worked for years, and we have not experienced a series of stapler malfunctions such as this until year 23 of practice. Considering our sleeve gastrectomy experience alone, we have performed more than 3,400 procedures to date, and this series of misfires began after the 2,900th case. Product lot numbers were also reviewed, and multiple lots were utilized during this study period.

SEAMGUARD is a SLR product that we believe strongly helps solidify our tissue substrate and has helped us achieve excellent results.1 SLR remains an area of controversy, and there are many experienced surgeons who do not use SLR with good results.9 In addition, we use green load staples for every firing in every case. This also significantly reduces our variability and likely minimizes the potential for stapler misfires due to a short staple height. We use electrocautery and fibrin glue on an as-needed basis.

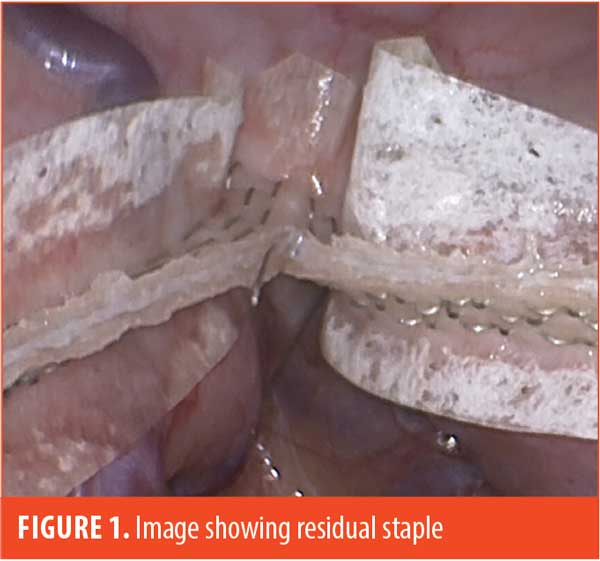

We have noticed that some unformed staples will collect in the crotch of the finished staple line, and careful attention is required to remove residual buttress material and residual staples prior to firing the next staple load (Figure 1).

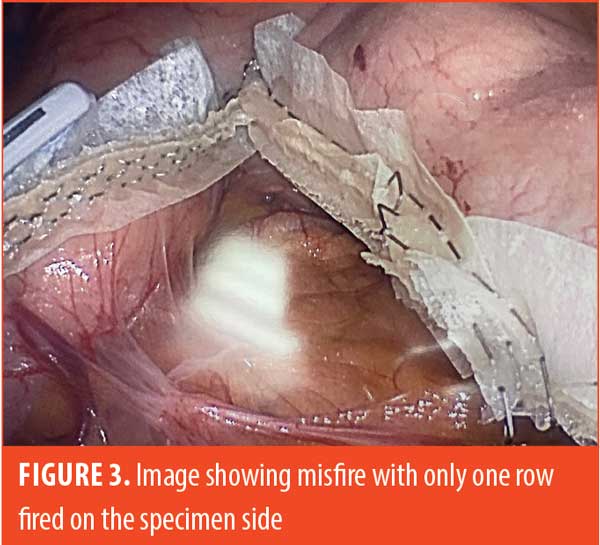

The staple load misfires have not occurred on the first firing, and therefore on the thickest tissue bite, but only after placing a reload into the stapler. Four of the six misfires occurred on the second firing at the incisura, and one each occurred during the third and fourth firing of the stapler. It is noteworthy that each Ethicon stapler reload does not utilize a fresh knife blade, which could theoretically cause issues after several firings. During a typical misfire, the powered stapler starts normally, then a mechanical click sound occurs midway during the firing process. After completion of the firing cycle, the stapler is removed and reveals that one side has a completed staple line and the other has no formed staples, with a gaping defect in the stomach. In four of these instances, the unformed staples were on the sleeve side, and in two instances, they were on the specimen side.

Some examples of our findings are shown in Figures 2 through 4. Figure 2 illustrates an embedded staple, which could potentially cause a misfire if not removed. Figure 3 illustrates a misfire in which there were three complete rows of staples fired on the gastric side and only one row of completed staples on the specimen side. Figure 4 shows a stapler firing and cutting, without actually firing any formed staples on the gastric side. The specimen side had three completed rows of staples.

Each of the misfires was treated in an identical fashion by hand-sewing the defect, taking care not to narrow the gastric lumen. Fibrin glue was then used to cover the suture line. These patients were placed on our standard postoperative diet advancement plan, and none of them have had problems postoperatively.

One previous stapler misfire three years prior to this recent series was identical to those stated above. That was our first stapler misfire requiring gastric repair, and it occurred during the second firing; the closure slightly narrowed the gastric lumen, although it was repaired over a 36 French bougie. This patient had a contained esophagogastric junction leak four weeks postoperatively that resolved uneventfully with stent placement. That patient is now more than three years out from her procedure and has maintained 90-percent excess weight loss.

Reported misfire rates have been noted in the literature, and a recent review of the Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience (MAUDE) database10 revealed infrequent events.4 Stapler malfunction is likely not as rare of an event as reported by safety profiles provided by manufacturers. Although the MAUDE database is a wonderfully useful tool, we suspect misfires are vastly underreported, handicapping the usefulness of some databases, and the MAUDE website wisely states its limitations. It takes some effort to report one of these instances to the MAUDE database or the manufacturer. Our observation in our own facilities revealed many instances where surgeons encounter misfires and instrument failures and take care of them without reporting them, with many believing that these events could be due to user error or an isolated event. The manufacturers have favored user error in most cases of our own reporting. However, these are primarily plastic mechanical devices that will fail despite the best safety profiles. In a literature review on the incidence of stapler malfunction, the authors found a reported incidence ranging from 0.022 to 2.3 percent.11 A prospective survey of laparoscopic surgeons reported that 86 percent had either experienced a stapler malfunction or knew someone who had had this experience, indicating that it is most likely an underreported phenomenon.12

Possible causes of misfires include mechanical issues (which can include a number of technical issues with a product), mismatching staple load to tissue thickness, inadequate stapler cleaning that results in tissue or residual staples in the stapler jaws, staple line crossing, residual buttress or staple remnants in the way of the next reload, and plowing of tissue by the stapler caused by overloading the capacity of the space allowed within the jaws, which could theoretically be worsened by buttress use.9 We believe that the most likely cause of this series of misfires is mechanical, secondary to reload malfunction involving the reload sled that pushes the staples out. This mechanism, which we hypothesize is breaking, would then fail to push the staples out and prevent staple formation but still result in cutting of tissue as the powered staple cycle is completed. Interestingly, we have brought this to the attention our hands-on Ethicon representative, who has relayed this to Ethicon engineers after each misfire incident. Ethicon has not formally acknowledged our recent series of misfires, now more than 10 months after it was first reported to them. Products involved in misfires and other malfunctions can remain with hospital risk management, resulting in significant delays for the manufacturer to examine their staplers. Furthermore, we acknowledge that we have successfully taken care of thousands of patients with properly functioning Ethicon products and staplers.

Conclusion

A more thorough and reliable database would be of significant benefit to hospitals and surgeons and would provide useful and more accurate information to stapler manufacturers. The MAUDE database is useful but provides information from reports that are made voluntarily to the United States (US) Food and Drug Administration (FDA).13 A database that reliably enters not only occurrences of misfires, but details of each misfire, would benefit the surgical ecosystem and allow for more viable discussions, including how to improve these essential mechanical devices.

References

- Woodman GE, Voeller GR. Sleeve gastrectomy performed with single staple height and bioabsorbable reinforcement in a single surgeon >2500 consecutive case series: is smart technology necessary? Obes Surg. 2022;32(3):690–695.

- Clapp B, Ponce J, DeMaria E, et al. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery 2020 estimate of metabolic and bariatric procedures performed in the United States. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2022;18(9):1134–1140.

- English WJ, DeMaria EJ, Hutter MM. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery 2018 estimate of metabolic and bariatric procedures performed in the United States. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2020;16(4):457–463.

- Clapp B, Schrodt A, Ahmad M, et al. Stapler malfunctions in bariatric surgery: an analysis of the MAUDE database. JSLS. 2022;26(1):e2021.00074.

- Almogy G, Crookes PF, Anthone GJ. Longitudinal gastrectomy as a treatment for the high-risk super-obese patient. Obes Surg. 2004;14(4):492–497.

- Batchelder AJ, Williams R, Sutton C, Khanna A. The evolution of minimally invasive bariatric surgery. J Surg Res. 2013;183(2):559–566.

- Qafiti FN, Yi S, Marsh AM, et al. The Evolution of bariatric surgery–from sewing lips to constructing the sleeve. Am Surg. 2022;88(7):1526–1529.

- Rawlins L, Johnson BH, Johnston SS, et al. Comparative effectiveness assessment of two powered surgical stapling platforms in laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: a retrospective matched study. Med Devices (Auckl). 2020;13:195–204.

- Sakcak I. Are stapler line reinforcement materials necessary in sleeve gastrectomy? World J Surg Proced. 2015;5(3):223–228.

- United States Food and Drug Administration. MAUDE – Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfmaude/search.cfm. Accessed 15 Dec 2020.

- Makanyengo SO, Thiruchelvam D. Literature review on the incidence of primary stapler malfunction. Surg Innov. 2020;27(2):229–234.

- Kwazneski D 2nd, Six C, Stahlfeld K. The unacknowledged incidence of laparoscopic stapler malfunction. Surg Endosc. 2013;27(1):86–89.

- United States Food and Drug Administration. MedWatch forms for FDA safety reporting. Current as of 15 Sep 2022. https://www.fda.gov/safety/medical-product-safety-information/medwatch-forms-fda-safety-reporting. Accessed 5 Dec 2022.

Category: Case Report, Online Only