YouTube® as a Source of Information on Healthy Weight Loss Plans: A Snapshot Analysis of Information Quality

Ms. Klumpp is Vice President and Editorial Director for Matrix Medical Communications in West Chester, Pennsylvania.

FUNDING: No funding was provided for this article.

DISCLOSURES: The author reports no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Bariatric Times. 2019;16(2):20–21.

Introduction

According to Pew Research Center, eight out of 10 adult internet users (59% of the adults in the United States) use the internet as a source of information on health-related issues, which makes seeking healthcare information the third most popular online activity in the United States. Specifically, 52 percent of internet users seek information on exercise or fitneass, and 49 percent seek information on diet, nutrition, vitamins, or nutritional supplements.1

YouTube, a popular and successful website, has up to 1 billion active users every month,2 and 73 percent of adult Americans are said to access YouTube regularly.3 The use of YouTube as a source of healthcare-related information for various disease states has previously been studied.4–7 In a recent study published in The Journal of Clinical and Aesthetic Dermatology,7 researchers examined YouTube for videos directed toward patients with psoriasis, specifically examining the content available via a search for “psoriasis treatment.” What the authors found was that the majority (nearly 80%) of the videos concerning the treatment of psoriasis were not from credible medical sources (i.e., most videos were posted by authors with no medical background). Only 7.1 percent of the videos on psoriasis treatment were posted by medical institutions or by verified physicians.7

We examined YouTube for videos directed toward individuals interested in weight loss, specifically examining the content available using the search term “healthy weight loss plan.”

Methods

Our initial search, which was first filtered by “relevance,” resulted in approximately 18,800,000 posts. We narrowed our search to videos posted “this year,” which resulted in approximately 5,120,000 video posts. Youtube displays search results using a continuous scroll (as opposed to displaying a set number of posts per page). For our study, we restricted our search to include the first 100 videos displayed in the list of results. We then excluded any video older than May 1, 2017, as well as those that were not in the English language. After excluding videos that did not meet our inclusion criteria, we were left with 32 videos for our analysis. We evaluated the 32 videos for the following characteristics: number of page views, thumbs up and down ratings, author profession/affiliation, the content of the video, if the authors provided scientific evidence for information in video, whether the authors promised results or made product claims, if the video was monetized by advertising, and if a product or service was being offered via the content of the video, the text under the author’s name or profile, or via an affiliated website.

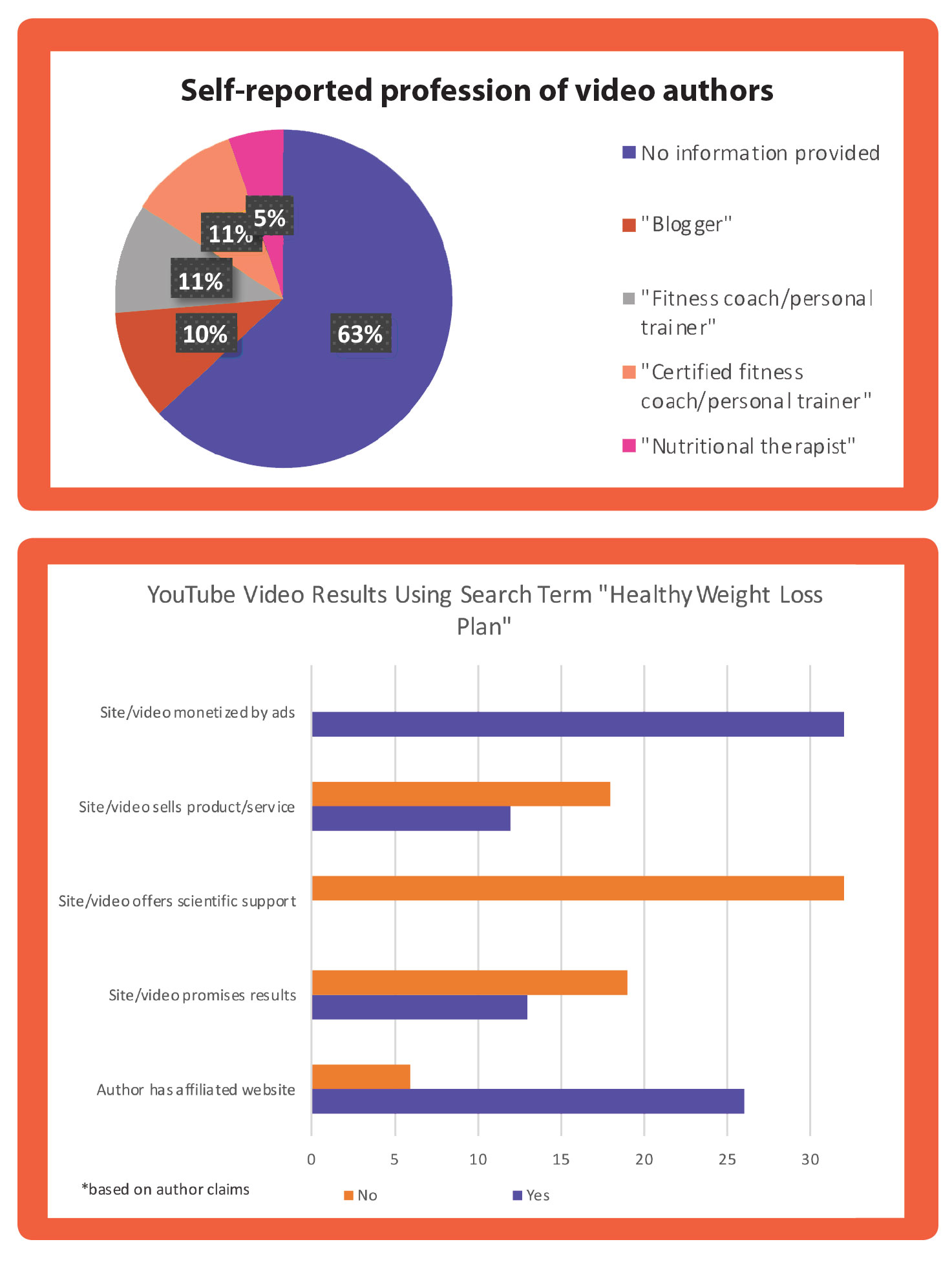

Authors. From our sample of 32 videos, there were 19 authors (i.e., some authors posted several videos within our sample). Only one of the 19 authors gave any indication of having a medical background (“certified as a nutritional therapist”), though we were unable to verify this claim. Two authors claimed to be “certified personal trainers,” one claimed to be a “personal trainer” (did not use the word certified), and one claimed to be a “fitness trainer.” Of the remaining 14 authors, one claimed to be a “health & a beauty blogger by profession,” one simply claimed to be a “blogger,” and the remaining 12 authors did not identify themselves by any qualifications or profession.

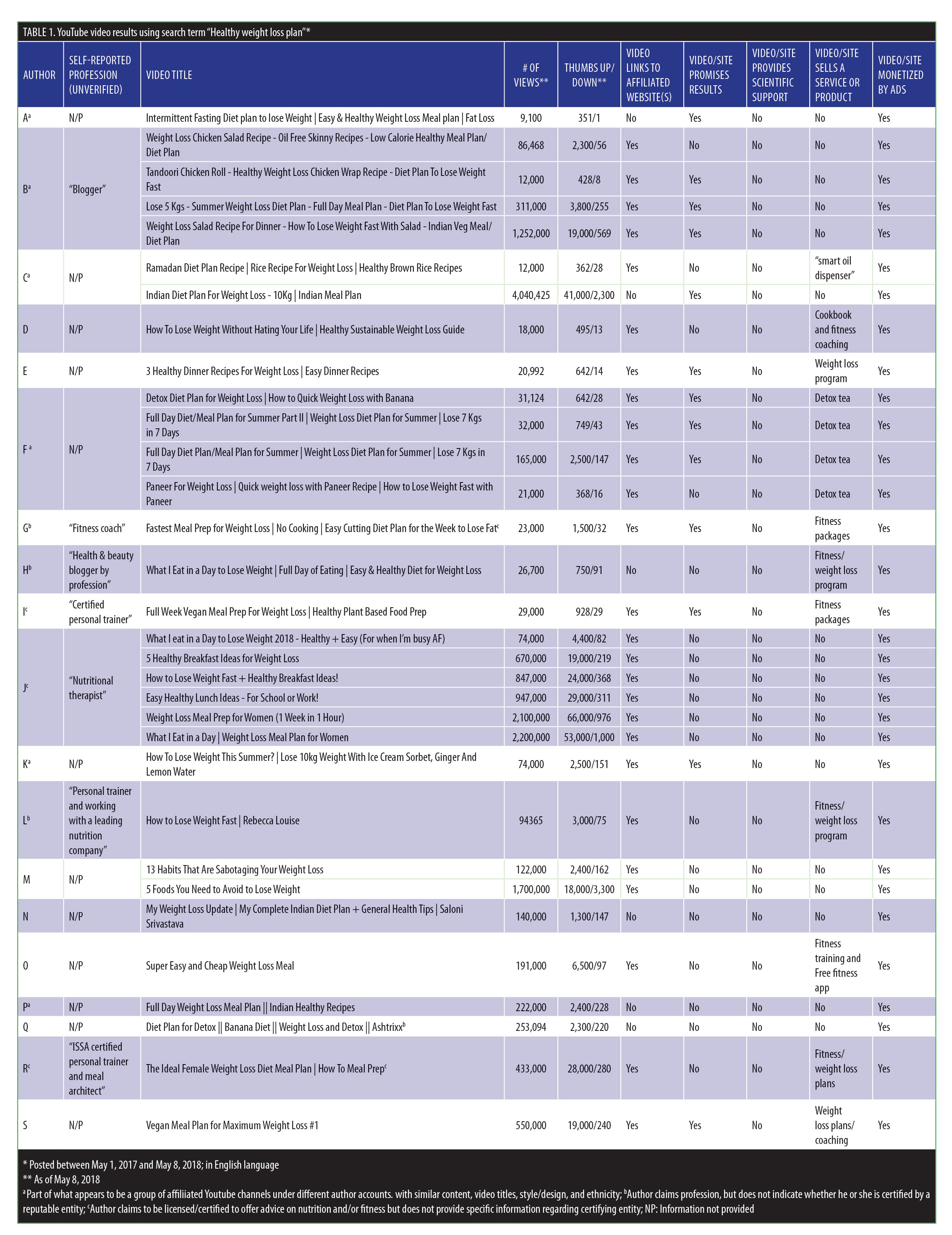

Content. Twenty-two of the videos described and provided recipes for either single meals or dishes or meal plans designed for weight loss (most included basic nutrition information [calories, fat, carbs, protein]), three described the benefits of and provided recipes for “detox” or intermittent fasting diets, five videos described the components of healthy living and/or a healthy weight loss plan (no recipes), and two videos provided lists of dos and don’ts of dieting (e.g. “5 foods you should avoid while dieting”). None of the videos provided scientific evidence nor acknowledged a medical institution for the information provided.

Promised results/claims. Eleven of the videos and/or their affiliated websites made promises or claims regarding the information presented either in the video or on the website (e.g., “lose 10kg in 10 days”). Two videos used what we considered to be exaggerated wording: One claimed “A Foolproof, Science-Based Diet Designed to Melt Away Several Pounds of Stubborn Body Fat in just 21 days,” and the other claimed “6 week body transformation, lose 20lbs or 5% body fat or money back.”

Sale of products or services/advertising. Twenty-one of the videos and/or their affiliated websites advertised products or services, including fitness/weight loss plans, cookbooks, clothing/beauty products, detox tea, and oils. All 32 of the videos displayed some type of advertising (i.e., generic ads [cars, tv, food, etc. or specific health/beauty products]) that either played before the video started or were displayed as popup ads during video play.

Discussion

There are several points of interest in our evaluation of these videos. Twelve of the 32 videos, while posted by a variety of authors, appeared to be part of a single entity, though what the entity was, exactly, was unclear. These 12 videos had similar, if not exact, wording in the titles and descriptive text, though the content varied slightly (i.e., different people were featured in the videos presenting separate but similar recipes); the same group of authors were all linked under “other relevant videos;” the videos had very similar production characteristics; the authors, all of whom appeared to be of Middle Eastern or Southern Asian descent, presented similar recipes characteristic of those geographical regions; and they all included links to the same products and services in the text under the author names. None of these authors indicated they were qualified to offer advice on nutrition or fitness, which, for one video in particular, was concerning to us as no scientific evidence was provided to support that the information provided was nutritionally sound advice (a 7-day detox diet in which the user was instructed to eat 25–30 bananas a day).

Another author posted six of the analyzed videos. This author was the only one who presented herself as a licensed health professional qualified to give advice on diet/nutrition (i.e., she identified herself as a nutritional therapist.) A nutritional therapist must complete a course or series of courses on nutrition to become certified. A seal stating “certified nutritional therapist” was displayed on the author’s website, but we were unable to verify her credentials.

One of the authors, who claimed to be a personal trainer and to be employed by “a leading nutrition company,” also appeared to be recruiting others to sell her fitness programs. An article on this author’s services that appeared in the Chicago Sun identified this author as being a National Academy of Sports Medicine certified professional trainer and stated that she works alongside top doctors and scientists — all possessing PhDs. None of the “top doctors” or “scientists” were identified.

The rest of the videos and authors offered similar types of information, i.e., mainly menu samples of weight loss programs. Generally speaking, the menus seemed reasonably healthy, and most of the authors offered some nutrition facts (i.e., calories, fat, carbs, protein). However, with the exception of one author who identified herself as certified nutritional therapist, none of the YouTube authors in our study appeared to be qualified to offer nutritional advice, which, for individuals with special dietary needs and/or comorbities related to overweight and obesity (e.g., diabetes, cardiovascular disease), might be problematic.

Limitations. There are several limitations to this study. First, we only evaluated results using one search term . More specific search terms might reveal different results. Additionally, we only examined 100 video posts out of, literally, millions; thus, our results might not be generalizable across the broad spectrum of videos tagged with the term “healthy weight loss plan.” And finally, because YouTube displays results in a continuous scroll (as opposed to a set number of results per page, such as with a Google search), it is difficult to estimate the number of video post titles a user would be exposed while viewing search results. We believed using 100 as our cut off for the number of videos included in the initial search would allow for a fair sampling of search results; however, this cut off number was more or less an arbitrary choice. Thus, the final number of videos included in our study (34) might not be respresentative of the number of search results the average YouTube user would consider viewing.

Conclusion

The internet is a popular source of information on a variety of topics, particularly healthcare, and is likely the first place a patient will go when seeking information on healthy weight loss. Unfortunately, the information patients are exposed to might not be from qualified sources. Our results suggest that the information provided on YouTube regarding healthy weight loss plans is of poor quality. Qualified healthcare clinicians should view the internet as opportunity to educate the public on various aspects of health and medicine. In particular, clinicians in the field of bariatrics should consider utilizing YouTube as an educational platform by posting evidence-based videos on medical weight loss and bariatric surgery for patients seeking information on weight loss.

References

- Pew Research Center site. Internet and technology. 11 February 2011. http://www.pewinternet.org/2011/02/01/health-topics-2/ Accessed May 11, 2018

- YouTube for Press. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/yt/about/press/. Accessed September 9, 2017. Accessed May 11, 2018

- Pew Research Center site. Internet and technology. 5 February 2018. Who uses Pinterest, Snapchat, YouTube and WhatsApp? Survey conducted Jan. 3-10, 2018. http://www.pewinternet.org/chart/who-uses-pinterest-snapchat-youtube-and-whatsapp/. Accessed May 11, 2018

- Adhikari J, Sharma P, Arjyal L, Uprety D. YouTube as a source of information on cervical cancer. N Am J Med Sci. 2016;8(4):183–186.

- Patel R, Chang T, Greysen SR, Chopra V. Social media use in chronic disease: a systematic review and novel taxonomy. Am J Med. 2015;128(12):1335–1350.

- Damude S, Hoekstra-Weebers JEHM, van Leeuwen BL, Hoekstra HJ. Melanoma patients’ disease-specific knowledge, information preference, and appreciation of educational YouTube videos for self-inspection. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2017;43(8):1528–1535.

- Lenczowski E, Dahiya M. Psoriasis and the digital landscape: YouTube as an information source for patients and medical professionals. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11(3):36–38.

Category: Brief Report, Past Articles